Transcription

CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECTTrend AnalysisCybersecurity at Big EventsZürich, November 2019Risk and Resilience TeamCenter for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich

Cybersecurity at Big EventsAuthor: Alice Crelier 2019 Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH ZurichContact:Center for Security StudiesHaldeneggsteig 4ETH ZurichCH-8092 ZurichSwitzerlandTel.: 41-44-632 40 s prepared by: Center for Security Studies (CSS),ETH ZurichETH-CSS project management: Tim Prior, Head of theRisk and Resilience Research Group, Myriam DunnCavelty, Deputy Head for Research and Teaching;Andreas Wenger, Director of the CSSDisclaimer: The opinions presented in this studyexclusively reflect the authors’ views.Please cite as: Alice Crelier (2019) Trend Analysis:Cybersecurity at Big Events, November 2019, Center forSecurity Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich.2

Cybersecurity at Big EventsTable of ContentsExecutive Summary41Introduction522.12.2Defining a Big EventConceptualizing a Big EventDefining a Big Event66833.1Cybersecurity at Big Events: Some Examples 8Why Is Cybersecurity Important for Big Eventsand Vice Versa?8Contextualization of the G20 Summits and theOlympic Games9The G20 Summits9The Olympic Games9Cyber Threats to the G2010Cyber Threats to the Olympics11Securing BE: What Does This Mean? Examplesfrom the G20 Summits and the OlympicGames13The cybersecurity-related organizationalchallenges of G20 Summits13Cybersecurity-related organizationalchallenges of the Olympic Games143.23.33.43.544.14.24.34.4Trends and Evolution in the CybersecurityLandscape of Big Events16Trends in the G20 Cybersecurity ThreatLandscape16Trends in the Olympic Games CybersecurityThreat Landscape17Trends in Organizational CybersecurityChallenges of G20 Summits and the OlympicGames17General Challenges in Securing Big Events18Systemic approach: BEs are complexsystems, and complex systems are fragile 18Identifying threat actors and theirmotivation/scope18Adopting a holistic risk assessmentframework18Implementing a follow-up process19Organizational processes195Conclusion and Further graphy223

Cybersecurity at Big EventsExecutive SummaryObjective and MethodsAs Big Events (BEs) like the Olympic Games or G20Summits become increasingly digitalized, concern isgrowing among officials and academics aboutcybersecurity. This is unsurprising, because a growingnumber of unsecured and unsafe programs, applicationsand devices and an overall lack of cyber-hygiene openthe door for the proliferation of nefarious cyberactivities related to such BEs. Moreover, BEs are soimportant for both organizers and host countries (interms of cost, mediated reach, reputational significance,soft power, etc.) that their associated cybersecurityaspects cannot be neglected, making BEs a particularlyinteresting object of exploration in the context ofcybersecurity.Consequently, this Trend Analysis (TA) aims toaddress the main issues regarding cybersecurity at BEs,using the G20 Leaders’ Summits and the Olympic Gamesbetween 2009 and 2019 as case studies. This TA intendsto answer the following questions: What is a BE andwhat are its various dimensions? Are there trends incybersecurity organization and processes related toBEs? What trends can be observed in terms of the cyberthreat landscape of BEs? What do they teach us aboutcurrent and future cybersecurity at BEs?This TA is based on an extensive literature reviewand analysis of a wide spectrum of white papers,journalistic coverage and academic literature.It should be noted that this TA focuses on BEsthemselves rather than on the general services on whichthey depend (e.g. transport, IT services, food supply,hotels, etc.).ResultsOverall, the paper points to the following keyfindings: First, the literature with regard to BEs is notextensive and mainly addresses sporting events, tourismand urbanism.Second, there is no holistic definition of BEs thatwould include both the Olympic Games and the G20Summits. Consequently, this paper defines the conceptof BEs and its various dimensions as follows: BEs are“ambulatory occasions of a fixed duration that a) attracta large number of visitors, b) have large (andinternational) mediated reach, c) come with large costs[ ], d) have large impacts on the built environment andpopulation”, e) attract significant numbers ofinternational attendees and spectators, f) exert politicalinfluence, and g) have cross-sectoral implications(Müller, 2015, p. 629).Third, trends have shown that both G20 Summitsand Olympic Games have expanded their cybersecurityorganization and processes over the past decade.Fourth, a comparative analysis and incidenttimelines indicate that, both the Olympics and the G20Summits were affected by largely the same types ofcyber incidents. The difference lies in the fact that G20related attacks mostly involve cyberespionage and areless aimed at disrupting the Summits or damaging theimage of the G20 or host countries, as is evidenced bytrends regarding cyberattacks and cyber incidents.Olympic Games-related attacks mostly have acybercrime background and are aimed at disrupting theGames or damaging the image of the Olympics or hostcountries. However, the number of cyberattacks of apolitical nature should not be underestimated, even inthe context of sporting nizational aspects and processes of the OlympicGames and G20 Summits as well as the associated threatlandscape helps to highlight the following organizationalprerogatives for cybersecurity at BEs:- Plan early- Prioritize cooperation and information sharingamong the public and private sectors, industry andother non-state actors- Create a shared mission and common cybersecuritygoals- Establish clear roles and responsibilities amongstakeholders- Incorporate cybersecurity into broader securityplanning (Dion-Schwarz, 2018, p. xii)- Include all levels of government in the CERT- Include subsidiarity in processes- Identifythethreatactorsandtheirmotivations/scopes- Adopt a holistic risk assessment framework- Consider geopolitical factors as centralFinally, BEs must be understood from a systemicperspective, especially given that these events dependdirectly and indirectly on their social context and havecomplex and unpredictable impacts on it.4

Cybersecurity at Big Events1 IntroductionBig Events (BEs) are not intrinsically a newphenomenon. Indeed, there has been a strong traditionof Big Events in both European countries and the USAsince the 19th century, with the Paris InternationalExpositions, the Brussels International Expositions, theWorld’s Fairs, the Olympic Games (starting in the 20thcentury), international political forums, etc.Until World War II, events of these types, especiallyexhibitions and games, were organized to showcase theculture, technological innovations and industrial powerof host countries. Events were attended by largenumbers of visitors – ranging from 5 to 30 million – andvast numbers of countries participated. Host countrieswould spend significant resources on the organization ofsuch events in order to “demonstrate their power”. Thiswas true in the past and is all the more so today. Forexample, Expo Milano 2015, an international registeredexhibition hosted by Milan, attracted more than 22million visitors and 145 participating countries with anofficial budget of 1.486 million (Expo 2015 S.p.A, 2018).Another, current example is the 2020 Tokyo OlympicGames with a budget reaching some 6.33 billion andaround 10 million expected visitors (Kyodo, 2019, p. 20;Mainichi, 2018).These are important events that attract extensivemedia coverage and have substantial societal andpolitical impact. They are therefore worth beingproperly cyber secured in our digitalized world.The exponential evolution of Information andCommunications Technology (ICT), its ubiquitousnature, the digitalization of BEs such as the OlympicGames or G20 Summits, as well as the increasingimplication of mass media in BEs have all added value tothese events, as broadcasting become a narrativevector. However, this added value has come at a cost, asthe emergence of an increasing number of unsecureddevices, programs and applications and an overall lackof cyber-hygiene have engendered new risks andallowed new threat vectors for cyberattacks to develop.This Trend Analysis (TA) addresses importantquestions about cybersecurity at BEs, using the G20Leaders’ Summits and the Olympic Games between2009 and 2019 as a framework:- What is a BE and what are its various dimensions?- Are there trends regarding cybersecurity-relatedorganization and processes at BEs?- What trends can be observed regarding the cyberthreat landscape of BEs?- What does this teach us about current and futurecybersecurity at BEs?Summits and Olympic Games. Section 3.1 highlightsorganizational challenges of cybersecurity at the G20Summits and the Olympics, while Section 3.2 and 3.3present two separate timelines of cyber incidents at G20Summits and Olympic Games over the period examined.Section 4 analyzes trends and developments in the BEcybersecurity landscape and general challenges ofsecuring BEs. Finally, Section 5 presents conclusions andfurther considerations regarding cybersecurity at BEs.This TA is based on an extensive literature reviewand analysis of a wide spectrum of white papers,journalistic coverage and academic literature. It focuseson BEs themselves rather than on the overall services onwhich they depend (e.g. transport, IT services, foodsupply, hotels, etc.). These services are important andneed to be addressed in the frame of a bigger researchpaper.In order to answer these questions, this paper startsby addressing the various dimensions of BEs. From thisbasis, it develops a holistic definition of BEs in Section 2.Section 3 addresses trends observed in relation to G205

Cybersecurity at Big Events2 Defining a Big EventDiscussions about “Big Events”, “Mega Events”, or“High-Profile Events”1 take place in many differentforums, ranging from academia to alorganizations, the entertainment industry and so on.Academic literature often comments on such eventswithout defining them. “Many of us seem to have anintuitive understanding what the term refers to: weknow one when we see one”(Müller, 2015, p. 627). Inthis regard, the Cannes Festival, the Summer or WinterOlympic Games and the G20 have in common the factthat they have been defined at least once as a MegaEvent, Big Event or High-Profile Event.Before addressing cybersecurity at BEs, it isimportant to know what exactly needs to be cybersecured: What is a “Big Event”? What terminologyshould this TA use and why? What kind ofconceptualization is best suited to BEs with regard tocybersecurity?2.1 Conceptualizing a Big EventFor consistency reasons, this TA will use the term“Big Events”, while also referring to “Mega Events” aswell as to “High-Profile Events”.The terminology related to BEs is rather new andonly emerged in the academic field from 1987, when theAssociation Internationale d’Experts Scientifiques duTourisme of Calgary addressed the impact of MegaEvents on regional and national tourism development.Since then, the concept of BEs has often beenassociated with entertainment, tourism and urbanism.For example, according to Swiss professor MartinMüller, “Mega Events are ambulatory occasions of afixed duration that a) attract a large number of visitors,b) have large mediated reach, c) come with large costs[ ], and d) have large impacts on the built environmentand the population” (2015, p. 629). For other academics,BEs are “[s]ignificant national or global competitionsthat produce extensive levels of participation and mediacoverage and that often require large public investmentsinto both event infrastructure, for example stadiums tohold the events, and general infrastructure, such asroadways, housing, or mass transit systems” (Mills andRosentraub, 2013, p. 239).Another definition comes from the New ZealandMinistry of Business, Innovation & Employment, whichstates that “From the government's perspective, a majorevent is something that: Generates significantimmediate and long-term economic, social and culturalbenefits to New Zealand. Attracts significant numbers ofinternational participants and spectators. Has a nationalprofile outside of the region in which it is being run.Generates significant international media coverage inmarkets of interest for tourism and businessopportunities” (Ministry of Business, Innovation &Employment of New Zealand, 2019).In terms of BEs, both academia and governmentdefinitions emphasize the following eight dimensions:Visitor attractiveness: Prior theories understand BEsas being primarily touristic, with the focus lying on thetouristic impact on the host country (Falkheimer, 2008;Müller, 2015). This is particularly true when it comes tosporting events, fairs and concerts, with the OlympicGames between Calgary 1998 and PyeongChang 2018,for example, selling an average of 1.34 million tickets(Gough, 2019). However, tourist attractiveness candiffer widely between one BE and another, as BEs suchas the G20 Summits are not primarily aimed at attractingtourists.Cost: This dimension correlates with visitorattractiveness because BEs evidently rely on theinfrastructure required for hosting them. Costs areincurred for transport, hotels, venues and otherinfrastructures for visitors as well as for organizing theBE itself, including temporary jobs and salaries, ICT,infrastructure and security. Here again, costs vary widelybetween BEs. Indeed, while the Rio 2016 SummerGames cost some 11.62 billion and the 2012 and 2018FIFA World Cups about 10.3 billion, the 2018 G20Summit in Buenos Aires cost 98.63 million (Muhanna,2018; Müller, 2015, p. 631; Reuters Staff, 2017a; Settimi,2016).Impact on the host country (urban transformation):This dimension correlates closely with both costs andvisitor attractiveness. Indeed, some BEs, for exampleOlympic Games, have a direct impact on the populationas well as on the built environment. Most of the time theinfrastructure required for BEs needs to be refurbishedor built (conference facilities, stadiums, etc.). Moreover,as aforementioned, the touristic aspect of certain BEsdrives the construction or upgrade of roads, hotels,logistics, ICT structures, etc., depending on the eventtype and size. Most of the time, host countries or cities“make a strategic use of mega-events to developinfrastructure and push urban renewal, often throughleveraging funds that would not be available otherwise”(Müller, 2015, p. 633). For example, the G20 Summit inHangzhou allowed the city to boost its tourism as well asdevelop its infrastructure, even though G20 Summits arenot thought of as inherently touristic events (Muhanna,2018; Z. Zhao, 2016).Media coverage: Academics agree that “anunmediated mega-event would be a contradiction interms” (Müller, 2015, p. 630). This can be explained as1“Almost all BEs are also high-profile, i.e. are “known about by a lotof people and receive a lot of attention from television, newspapers,etc.” (Cambridge Dictionnary, n.d.).6

Cybersecurity at Big Eventsfollows: From a societal point of view, mass media is tobe considered as a cross-sectoral (social, political,corporate, and cultural) system. At the same time, thegenerally increased focus on media needs to be seen inthe context of a contemporary societal shift led by thequasi-exponential development and ubiquitous natureof ICT. Indeed, media has become as omnipresent as ICTand “saturates and influences all levels of society, fromeveryday life (such as the private home) to globalinstitutions (such as the sports industry)” (Falkheimer,2008, p. 82).This global aspect of media is very useful for thecountries hosting a BE and for all sectors involved inrunning it. Indeed, media campaigns and high exposureare likely to impact positively on a host country’s image,provided they are well organized and well led: All of theeffort a country has gone to in order to host a BE (visitorattractiveness, cost, urban transformation, etc.) isshowcased internationally by media coverage. However,any negative observations by the media would besimilarly highlighted and could cause reputationaldamage. Consequently, media coverage of BEs is usuallyproactively “integrated into the total place brandstrategy” (Falkheimer, 2008, p. 83).Moreover, media coverage can differ widelybetween one BE and another: In the context ofentertainment or sporting events, media do not onlyrelay information, but also create entertaining content.As a result, media commercial value (broadcastingrights) can reach in excess of 2 billion (Olympics or FIFAWorld Cups). However, in the context of internationaland/or political and/or economic BEs, media would playa more informative and persuasive role.Size: This TA will, for consistency reasons, considerthat an event is big enough to be considered as a BEwhen it can be categorized as such under both theclassifications of Müller (Major, Mega and Giga events)and the New Zealand Department of Business,Innovation & Employment (Major and Mega events)(Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment of NewZealand, 2019; Müller, 2015, p. 637). However, someevents, such as the G20 Summits will still be regarded asBEs, despite their size not fitting either of the abovementioned categories, because they meet all of theother criteria. Moreover, their political influence is tooimportant to be ignored.From a strictly technical point of view, however, alarge network that needs to be secured is still a network,regardless of whether it relates to the Olympics, theWorld Economic Forum (WEF) or the G20. Theapplicable security processes are identical, and only themeans used, the visibility of the network and the volumeof data involved vary, sometimes exponentially.Internationality: This dimension, which isparticularly important for governmental definitions ofBEs (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment ofNew Zealand, 2019), implies both an internationalaudience and international attendees, resulting in theaforementioned mass media coverage. This dimensionis the only one which does not differ drastically betweenone BE and another: The level of internationality, forexample, remains the same whether looking at theOlympics or the G20.Political influence: The literature, when referring toBEs, does not usually address their political dimension.However, this dimension is of considerable importance.First, some BEs, such as the G20 Summits or WEF, areintrinsically political events that provide a platform fordiscussions between various state and/or non-stateactors at a strategic level. Second, political BEs and alsosporting events are directly linked to the notion of“show of force” or “soft power”. Indeed, Raveneldescribes major sporting events in the following terms:“It’s a geopolitical message: we are a great powerbecause we are able to host a major sporting event. Thatis the definition of soft power – the ability to assert one’spower through means other than military” (Burnand,2012, p. 1).Soft power is closely interrelated with the mediationaspect. Indeed, states often use BEs, regardless of theirtype, to promote their image or “brand” worldwidethrough media coverage. Image is central here, becauseit reflects a nation’s “prestige”, which in turn is the focusof international affairs theories addressing soft power.Prestige is also considered to be complementary to“traditional material forces” – namely military force(Burnand, 2012; Grix and Houlihan, 2014).In other words, the act of hosting a BE allows acountry to display its cultural, political and foreign policyvalues as well as its economic power. Indeed, afteranalyzing sporting BEs, Grix and Barrie concluded that“Staging sports mega events (and BEs in general) is,however, more and more about projecting (soft) powerand achieving foreign policy goals using non-materialmeans” (2014, p. 1).Cross-sectorality and systemic approach: All BEs,whether political, economic or entertainment-oriented,touch on all sectors of society because their organizationimplementation and conduct draw on all of thesesectors (logistics, industry, health, urbanism, economy,politics, security – and in some cases, like the WEF, theArmed Forces). Moreover, from a systemic perspective,the resulting web of synergies affects and is affected bythe direct and indirect environment through complexinteractions. Applying a systemic logic, the BE and itsenvironment ultimately become one. Here again, thesystemic approach of the BEs is a broad and interestingsubject that should be analyzed in the frame of adedicated research paper.Cooperation and information sharing: Thisdimension is linked to the cross-sectoral dimension.Organization a BE requires close collaboration andinformation sharing between the private and publicsector, not only in a domestic context, but also betweenthe national and international levels.7

Cybersecurity at Big Events2.2 Defining a Big EventBased on the aforementioned dimensions of BEs,and inspired by Müller’s work, a definition of theconcept can now be proposed, according to which BEsare: “ambulatory occasions of a fixed duration that a)attract a large number of visitors, b) have large (andinternational) mediated reach, c) come with large costs[ ], d) have large impacts on the built environment andpopulation”, e) attract significant numbers ofinternational attendees and spectators, f) exert politicalinfluence, and g) have cross-sectoral implications(Müller, 2015, p. 629). The extent to which a particulardimension is expressed in any given BE will differbetween events.3 Cybersecurity at BigEvents: Some ExamplesOver the last decade, ICT has become ubiquitous andhas evolved to such an extent that it is now an enablerof spectacular events. This is true for international fairs,major concerts, sporting events and economic orpolitical meetings alike, all of which rely increasingly onICT in their overall structure (e.g. timers, securitycameras, magnetic or RFID badges, microphones,translators, mobile applications, etc.). These are allexamples of “direct ICT”, which is immediatelyresponsible for the proper and smooth running of a BE.However, it is important to remember that BEs alsodepend on extensive “indirect” infrastructure and publicproviders such as ICT providers, hotels, transportation,etc. that are not being considered here. Both direct andindirect components of BEs have opened the door fornew cyber risks and threat vectors.This section aims to identify the cyber threatsassociated with BEs by using the evolution ofcybersecurity organization processes as a frame andexamining timelines of cyber incidents at two major BEsfor the period between 2009 and 2019: the G20Summits and the Olympic Games. A comparativeanalysis then identifies relevant trends, which arefurther addressed in Section 4. The Olympics and theG20 Summits are both sufficiently similar and distinctiveto extract lessons learned from the full spectrum of BEs.Section 3.1 explains why cybersecurity is importantin BEs and why BEs are important for cybersecurity.Section 3.2 contextualizes the G20 Summits and theOlympic Games, while Sections 3.3 and 3.4 provide anoverview of cyber incidents affecting the G20 Summitsand the Olympics. Section 3.5 addresses theorganizational setup and processes for securing the G20Summits and Olympics in cyberspace.3.1 Why Is Cybersecurity Important forBig Events and Vice Versa?Given the range of dimensions impacted by BEs,cybersecurity is a crucial aspect of organizing suchevents. Indeed, broad media coverage, high investmentsand the fact that host countries use BEs as geopoliticaland soft power platforms make them tempting targetsfor cybercriminals, hacktivists, and nation-state actors.Accordingly, BE organizers and host countries have toomuch to lose if they fail to take cybersecurity seriously(i.e. reputational damage, loss of future foreigninvestments, loss of money already invested, etc.).However, it is also true that BEs are important forcybersecurity. The organization of Big Events requiresclose collaboration between a host country’s private andpublic sectors. Similarly, BEs are usually coordinated atboth the domestic and international level. The resulting8

Cybersecurity at Big Eventsexposure and need to deconflict can constitute goodlearning opportunities for sharing knowledge, testingrisk management infrastructures, and addressingbroader security risk factors. The Japanese government,for example, has massively tested and reported onissues of Internet of Things (IoT) security across theentire country in order to provide better security for the2020 Olympics and respond to the increasing problem ofthe IoT. BEs can be seen as opportunities to specificallyenhance domestic and international collaboration andtest in-country crisis response mechanisms, as theirorganization supports the following:- Checking national cybersecurity and cyberdefensecapabilities, the state of play and landscape in thisdomain- Testing national CERTs and their capability to workalong with other national and internationalcybersecurity actors (crisis simulations, riskmanagement exercises, war gaming, etc.)- Training individuals and companies- Business opportunities for the private sector, as ITand cybersecurity companies demonstrate theircapabilities of addressing the challenges associatedwith BEs- Learning: If BE organizers have knowledge-sharingprocesses in place (e.g. handover-takeover),cybersecurity can be improved with each new event3.2 Contextualization of the G20 Summitsand the Olympic GamesThe G20 SummitsFounded in 1999, the G20 or Group of Twenty is aninternational forum focused on economic and globalissues. It contains two tracks: a Leadership track, alsocalled Sherpa track, and a Finance Track. Its membershipconsists of 19 individual countries2 and the EU. Otherfinancial entities like the World Bank (WB) and theInternational Monetary Fund (IMF) also participate(G20, 2019). According to the aforementioned definitionof BEs, G20 Summits as well as other high-profilesummits represent an investment for host countries, notonly in terms of organizational aspects, but also becausehost cities often take events of this nature as anopportunity to update their infrastructure (Z. Zhao,2016). This is not always the case, though, due to timeand budget constraints. Moreover, the international andpolitical dimension of such events goes hand in handwith a high mediated reach. Even if these events are notmeant to attract tourism and are not comparable in sizeto the Olympic Games, they meet seven of the nineabove-mentioned dimensions: cost, impact on the hostcountry (urban transformation), media coverage,2List of member countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada,China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico,internationality, political influence, cross-sectorality,and cooperation and information-sharing.Since the G20 Summits are highly mediatedgeopolitical microcosms – consisting in both formal andinformal meetings between world leaders – shrouded ina veil of intransparency, they are exposed to a higherlevel of threat than other high-profile political meetings(Annual and Spring Meetings). Also, the G20 Summitsare frequently targeted by espionage campaigns andmassive protests on climate change and trade policies,which can also extend into cyberspace (Abedi, 2017;G24, 2019; Kaffenberger, 2018).The Olympic GamesThe modern Olympic Games are leadinginternational sporting events held all over the world, inwhich a large number of athletes (amateur, professionaland top professional) represent their countries in abroad variety of competitions. The Summer and WinterOlympic Games are both held every four years (Youngand Abrahams, 2019).These kinds of BEs are hugely attractive to visitors.For example, the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio deJaneiro boosted the country’s tourism to unprecededlevels, with some 6.6 million international touristsvisiting Brazil for the occasion (Termèche, 2017). Thesevisitor numbers were, of course, not unprecedented,and it is widely accepted that the Olympic Games aremajor events due to their substantial size and impressivevisitor attractiveness (Müller, 2015). These dimensionsimpact on the cost of the event, which is necessarilyhigh, and frequently leads to major zation of all societal sectors (cross-sectorality).Moreover, wide media coverage is central to BEs such asthe Olympic Games because the associatedbroadcasting rights are extremely lucrative.Consequently, “large events are nowadays mediatedrather than experienced” (Müller, 2015, p. 630).Moreover, according to Rid, “the Olympics have alwaysbeen the most politicized sporting event of them all”(Greenberg, 2018). Given the above considerations, theOlympic Games meet all of the aforementioneddimensions for defining a BE.For Greenberg, “the Olympics have always been ageopolitical microcosm: beyond the athletic match-ups,they provide a vehicle for diplomacy and propaganda,and even, occasionally, a proxy for war” (Greenberg,2018). This – and also other reasons that will beaddressed below – may be one of the reasons why theOlympics are often targeted in cyberattacks.Republic of Korea, Republic of South Africa, Russia, Saudi Arabia,Turkey, United Kingdom, United States of America (USA).9

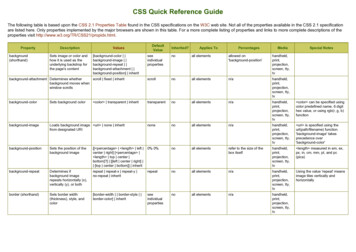

Cybersecurity at Big Events3.3 Cyber Threats to the G20Diagram 1 shows a timeline of the most notablecyber incidents relating to the G20 to help identifytrends.Diagram 1: Timeline of the most notable G20-related cyber incidents 2009-2019Before going further into this TA, it is important tonote that, because of the highly political and strategicnature of events such as the G20 Summits, most of theliterature relating to the actual number and types ofcyber incidents that occurred

cyber incidents. The difference lies in the fact that G20-related attacks mostly involve cyberespionage and are less aimed at disrupting the Summits or damaging the image of the G20 or host countries, as is evidenced by trends regarding cyberattacks and cyber incidents. Olympic Games-related attacks mostly have a