Transcription

TAKING CHARGE OFPRINCIPAL SUPPORT:An In-Depth Look atNYC Leadership Academy’sApproach to CoachingPrincipals

NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG2

TAKING CHARGE OFPRINCIPAL SUPPORT:AN IN-DEPTHLOOK AT NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY’SAPPROACH TOCOACHINGPRINCIPALSCopyright 2015 NYC Leadership Academy. All rights reserved.

NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG2JPG Photography

3TABLE OF CONTENTSMessage from the CEO5The Real Power of Coaching: Developing the Professional Practiceof Principals in Support of School Improvement7Our Vision for Impact11An Overview of Our Coaching Work13Coaching Aligned to Leadership Standards19NYCLA’s Approach to Coaching27Understanding the Landscape: Assessing Current Leadership Supports37Program Design43Coach Development53Program Evaluation61A Final Word65Additional Supports Available66Endnotes67NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG

NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG4

5MESSAGE FROM THECEONYC Leadership Academy has been working with school leaders in New York City andacross the nation on behalf of students for more than a decade, and we are proud ofour work and what we have been able to accomplish. We’ve been developing leadersand helping build effective, contextually relevant school leadership programs sinceour founding.During the 2013-14 school year, we coached more than 400 principals in New York Cityalone, and according to our data, 96% of those principals agreed that coaching positivelyimpacted their leadership practice.As we have developed our coaching model and deepened our coaches’ practice, ourwork has also expanded in scope. To date we have partnered with 38 districts, states,and organizations across the country to help build principal coaching programs anddevelop local capacity to support and empower leaders. In addition to our coaching workfor the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE), we have also directly coachedschool leaders for the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) and the SchoolDistrict of Philadelphia (SDP).While our coaching model has been deepened through lessons learned from adaptingour work to the needs of different contexts within school systems, our belief in standardsbased, facilitative coaching as an essential tool for leadership development has remainedconstant. Whether we work with coaches, district leaders, or directly with principals, wemaintain the core belief that coaching is in service of schools and, ultimately, of students.Irma ZardoyaPresident and CEOJuly 2015NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGAs we celebrate our first decade of service, we are excited to share in this guide thewealth of experience we’ve gained in the field of school leadership coaching. We offerexamples of how other districts have, with our help, adapted our approach and createdsustainable support systems for their school leaders. We hope this guide will provideinspiration for other school systems and partner organizations that are also focused onsupporting and advancing effective school leadership practice. Together, we can developand support school leaders in their increasingly complex work, so that all students canthrive and succeed.

NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG6

7THE REAL POWER OF COACHING:DEVELOPING THE PROFESSIONALPRACTICE OF PRINCIPALSIN SUPPORT OF SCHOOLIMPROVEMENTOne of my fondest moments from my time at NYC LeadershipAcademy took place in the principal’s office of a Manhattan highschool. A member of our coaching staff and I were visiting a firstyear principal, a powerhouse of a woman who had been hiredto turn around a very complex high school that was slated forpossible closure.The coach had been a teacher, an assistant principal, a principal, and an assistant superintendentduring his much-celebrated career. He was nowa dedicated coach, serious about his coachingpractice, and eager to learn new coaching skills,different from those he used in his supervisorycapacities. Having honed his questioning techniques, he was able to reflect back the assumptions his principals were making in a way thathelped them see limitations and create possibilities. As he was profoundly invested in the success of school leaders as a mechanism towardstudent achievement, he was interested in deepening his coaching skills in order to maximizeevery possible leadership learning opportunity.The pressure was on this first-year principalto make swift changes that would result inmeasurable student performance gains. Havingspent several years as an assistant principal ata higher-performing high school, she was takenaback by some of the realities she encountered.Teacher morale was low. Student performancewas low. Students in their second and third yearswere not on track to graduate. Attendance forboth students and teachers was abysmal. In priorcoaching sessions, she had done some rootcause analysis with her coach and determinedthat attendance was an important place toNYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGThe purpose of our visit was two-fold. First, therewas the regularly scheduled coaching sessionbetween the coach and the principal in whichthe two would step away from the day-to-dayactivities, reflect on her improvement efforts andleadership practices, and strategize for contin-ued improvement. Second, the meeting was anopportunity for the coach to get coaching support as part of an individualized “master class” inwhich I would observe coaching sessions, andthen reflect back to coach and principal whatI was observing in the dynamic in an effort tomake the coaching as effective as possible. Inessence, I was there to coach the coach.

8intervene. If she could boost attendance, it wouldbe an important first step toward raising studentperformance.NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGThe coach had given me some backgroundinformation on the principal before we met withher together. She was organized. She was courageous. She was fierce. She was committed tomaking a difference in her new assignment. Shewas very quick to determine “solutions,” at timesprior to fully exploring the “problem.” She wasworking around the clock and was tired. She didnot trust many staff members. She was developing trusting relationships with individual studentsand often aligning herself with them in theirstruggles with teachers. Her teachers seemed tofear her.The coach was concerned that this principal wasmaking a common rookie misstep—rather thanfiguring out how to collaborate with the teachingstaff, this principal was trying to work directlywith students and fix the problems herself. Suchstrategies, this coach knew, might have somepersonally gratifying short-term wins for theprincipal, but it was not a sustainable solutionthat engaged or affected the system dynamicsof the school. Without teacher engagement inthe improvement efforts, very little improvementwas likely to happen. The coach felt he had diagnosed the situation fairly, but was struggling tofigure out how to move the thinking and behavior of the principal. He had great respect for her,and felt that any challenge to her approach mightseem like a betrayal, as she was bombarded withwhat she perceived to be resistance from herstaff and pressure from her supervisors. Findingthe space in which she felt fully supported yetpushed to grow had been a challenge.The three of us sat around a table to discuss theschool’s attendance policies and practices.The principal started by explaining that sincethe last coaching session, she had learned thatpart of the attendance problem was not actuallyattendance, but rather how the school wastaking attendance.She started with, “Last time you were here yousaid ‘go deeper into the problem.’ So I did. Andguess what? The teachers aren’t taking attendance right.” The coach started in, “What do youmean by ‘right’?” The principal’s frustration withher situation was evident: “I mean that they markkids absent, and then I see the same kids here.”The coach continued, “Why do you think thatis?” The principal replied, “Because they don’tseem to care.” The coach glanced at me andcontinued, “Why do you think they don’t care?”The principal looked at him squarely and said,“Because if they cared, they would get it right.”Struggling for the next question to ask, the coachlooked at me and said, “Ok, this is where I getstuck.” To which I asked the principal, “What isthe actual system for taking attendance?”The ensuing conversation revealed generalconfusion about the school’s attendance-takingpractices. The principal described a systemthat was not consistent between teachers, asystem that suggested that accuracy did notmatter, a system that she inherited from herpredecessor. Without an advisory program inplace, attendance had been a task assigned tothe third-period teachers, but not all studentshad a third-period class. “So,” I asked, “who isthis attendance system good for?” The coachand principal answered in unison: “Nobody.” Bydelving deeper into the problem, the principaland coach explored how even the most caring

9of teachers would likely not get the attendanceof students without a third-period class right, andthat an important first step was to determine amore reliable system that was more workableinto the school day. Instituting an advisory program was a longer-term goal of the principal’s;she was not sure how to solve the short-termproblem. She realized that given how differentlythis school was organized from her prior school,she felt lacking in options that might work here.The coach saw an opportunity: “Who could helpyou figure out what might work here?” The principal saw the same opportunity. “The teachers,”she replied.Coaching is a powerful tool for supporting principals, particularly early in their careers. By askingquestions that help leaders delve deeper intothe challenges they encounter, by exposing theirassumptions, and by supporting them throughtheir growth, coaches provide an importantservice to school systems faced with leadership turnover at the school level. This guideshares the learning accumulated over nearly adecade of work at NYC Leadership Academy.The work of coaching has evolved over time,in both content and structure, from a looselyorganized group of sitting and retired principalsimparting wisdom, to a highly trained cadre ofveteran leaders deeply committed to continuouslearning and honing of their coaching practice.In the course of NYC Leadership Academy’sexperience, we have coached more than 1,600new principals, many of whom have requestedcontinued coaching year after year.Leadership coaching is an investment that manydistricts and states are now making in orderto address the challenges of higher principalturnover rates in the context of policies gearedtoward principal accountability. In the context ofthat pressure, coaching is important support.The work of coaching is individualized, butnot on behalf of the individual. The ultimatebeneficiary of leadership coaching is intended tobe the school-age students reliant on effectiveleadership. The coaching process is creative,responsive, and geared toward building a leader’s capacity for making change, for improvingprocesses, and ultimately for coaching others.The pages that follow explore and explain NYCLeadership Academy’s approach to coaching.It is our hope that system leaders, coaches,and principals use the information here tocreate more sustainable systems for leadershipsupport, ultimately benefiting the students wecollectively serve.Sandra J. SteinFormer CEO of NYC Leadership AcademyJuly 2015NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGCoaching is not about filling the voids and deficits assumed to be part and parcel of a new job.It is about developing a professional practice ofaction and reflection, of probing current systemsand exploring possibilities. While much of ourcoaching focuses on early-career principals inNew York City, we believe that coaching is abroader and more flexible support that can beuseful for leaders facing different challenges:principals placed in turnaround schools andprincipals working to develop the capacity ofleadership teams.

NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG10JPG Photography

11OUR VISIONFOR IMPACTSince our founding, NYC Leadership Academy (NYCLA)has been committed to improving outcomes nationwide,particularly for the most vulnerable students, throughhigh-quality school leadership. We do this by buildingthe capacity of education systems across the country todevelop and support their own leaders, bringing a standards-based and social justice-rooted approach to schoolleadership development to support our country’s mostunderserved students. The future of education requireswell-trained leaders who can improve the achievementof students who need it most—leaders with a sense ofurgency and commitment to all students, who can buildand lead effective school teams. We are dedicated to theongoing development of such leaders.NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGTo learn more about our work, including our preparation of aspiring principals, coaching and support forcurrent principals, and school leadership consultingacross the country, please visit our website atwww.nycleadershipacademy.org.

12NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG Jerry Speier, 201299%of NYCLA-coachedprincipals in New York City report thatcoaching improved their leadership practice.

13AN OVERVIEW OFOUR COACHING WORKSchool leadership is second only to teaching among school factors that impact student success,1 and is therefore critical for statesand districts to get right. And because the impact of leadership isgreatest in schools with the greatest needs,2 NYCLA is committedto improving school leadership on behalf of the most vulnerablestudents.A highly effective principal has been shown toincrease his or her students’ standardized testscores up to 10 percentile points in just oneyear.3 Under effective principals, ineffectiveteachers tend to leave of their own accord, andeffective principals are more likely to hire andretain more effective teachers.4School leadership, then, is a crucial lever forachieving change in education. As principalshave been given more control over factorsinfluencing their schools, their job descriptionshave transitioned from building managementto encompassing the complex work of change,including leading instruction, impacting schoolculture, managing resources, and evaluatingteachers.THE CASE FORCOACHINGThe 2012 MetLife Survey of the AmericanTeacher, which includes a survey of principalsnationwide, found that 75% of principals agreethat their jobs have become too complex.5This view was shared by principals acrossdemographics such as school level, location, andproportion of low-income and minority students.We believe that school leadership coachingis the best tool to help principals navigate thiscritical, complex work.“COACHING” VS. “MENTORING”the work of supporting school leaders. For the purpose of this guide, “coaching” refers to the practiceof building the leadership practice, skills, and behaviors of school leaders, ultimately to create a changein outcomes for students in schools. Our work often comprises a one-on-one coaching relationship, butour coaches have also done this work with school leadership teams and in other group settings. Otherprograms may refer to this same type of work as “mentoring.”NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGThere is wide variation in the use of the term “coaching” versus “mentoring” across the field to refer to

14The principals we coach experience daily theold adage that “it’s lonely at the top.” And whilecoaching is not about providing a “friend” to aprincipal, it is about providing a thought partnerin the field. Principals hold teachers and schoolstaff accountable, just as principals themselvesare held accountable according to an increasingly stringent set of metrics. Coaching is aboutproviding a principal with the support he/sheneeds to make necessary leadership behaviorchanges on behalf of schools and students.While no one has yet produced research directlylinking principal coaching to student outcomes,we know from our own practice that the schoolleaders we work with value their coachingexperience highly. They value coaching not justas a series of feel-good conversations, but asa tool that positively impacts their leadershippractice. Last year in New York City, 92% of the400 principals we coached agreed that coachinghas led to improvements in classroom instructionin their schools. Ninety-five percent agreed thatcoaching has led to improvements in their abilityto develop the capacity of others, and 94%agreed that coaching has led to improvements inschool culture.In addition to data about principal satisfactionwith coaching, research has shown that jobembedded learning is the most effective way foradults to gain new skills and knowledge, and thatcontextualized, targeted coaching support canimpact principal practice.6COACHING FOR REFLECTION AND FOR ACTION“As coaches, we want principals to develop a reflective disposition. This is notonly for their own learning but also because the reality is that schools are political institutions and leaders need to be able to consider issues from a variety ofperspectives and understand the implications of their decisions at the systemslevel. The best leaders routinely step back and take into account different pointsof view. But reflection is not enough. Principals also need to act in a timely wayand communicate their decisions effectively to a wide range of stakeholders.The fact is that the work can be anxiety producing, but we are there to help principals identify root causes of problems, think through the implications of theiractions, and take the steps needed to build support and capacity of others in theschool. We must be willing to push principals out of their comfort zone. Oncethey build their sense of self-accountability and commitment to change, they beNYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGcome more willing to make appropriate changes on behalf of student learning.”515coaches have beentrained in our facilitative, competencybased coaching model.—Mark Levine, CoachNYC Leadership Academy

15WHAT ISCOACHING?In talking about NYCLA’s coaching model, it’simportant to begin with what coaching is not. Coaching is not about a coach directing theprincipal to take certain actions. Coaching is not a therapy session, nor achance for the principal to talk about whateveris on his/her mind. Coaching is not about providing a friend in thefield whose main purpose is to make principalsfeel better.Rather, in our model:In our model, two drivers shape what coachingpractice looks like in the field:1. The school’s needs. Coaching isgrounded in what needs to happen at theschool level. What are the goals that theprincipal and the school are working toward?These goals are informed by, among otherthings, student achievement data, the current level of instruction, and the state of theschool’s culture.2. The principal’s leadership needs. Allcoaching work starts with the question, whatdoes the principal need to know and be ableto do in order to move the school closer toits goals? Leadership needs are diagnosedagainst specific leadership competencies,discussed in the next section.NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG Coaching is primarily facilitative; coachescreate an environment in which the principalengages in critical and targeted reflection onhis/her practice, with the goal of facilitatingthe paradigm or behavioral shifts necessaryfor the principal to develop his/her leadershipcapacity. Coaching is based on clear leadershipcompetencies intended to build the leadershippractice, skills, and behaviors of schoolleaders, ultimately in the service of changingoutcomes for students. Coaching is providing principals with a criticalthought partner who can create a space forthe principal to be reflective about his/her ownbehaviors and decision-making and can pushthe principal’s thinking. Coaching is an iterative process—as principalsgrow in capacity, engaging with their coachcontinues to move their leadership practiceforward in order to move the school where itneeds to go.We believe that through coaching, principals canlead instructional and cultural change in theirschools. Equity is a foundational value in ourapproach, embedded in all our work. Coachesare committed to their work with principals notfor the principals’ sake, but on behalf of students.

achingSupportPrincipalNeedsOur coaches support the principal in makingchanges in instructional quality and organizational capacity at the school level. These twoelements drive change that impacts students.PURPOSEOF THIS GUIDENYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGThis guide is a call to invest in school leadershipdifferently and better. Principals are being heldaccountable for more aspects of impactingstudent outcomes than ever before, and theydeserve the best possible support to help themsucceed.This guide shares our experience developing ourcoaching model, including our use of leadershipstandards, our approach to coaching, and thepurposeful decisions we’ve made around program design, ongoing coach development, andprogram evaluation.Our aim is to unpack our own thinking and intentionality about the decisions we’ve made andwhy we’ve made them. We provide an look at the core elements of our approach tocoaching, including our lessons learned and thequestions we are still asking ourselves abouthow to coach more effectively. Existing principal coaching programs canexplore our coaching model—including thefoundation of standards, our facilitative,competency-based approach, and programdesign—to spark ideas for ways to strengthentheir practice. New principal support programs in districts,states, and organizations can use this guide todevelop the most appropriate coaching solutions for their local needs. District leaders may consider how currentschool leadership support is being handled,and decide how desired outcomes can bebetter met to reduce principal turnover andimprove principal effectiveness. State policymakers can incorporate lessonslearned regarding the value of investing injob-embedded, standards-based coachingsupport for school leaders as they devisepolicy responses to the challenge of supporting principals to become more effective.

17INSIDE A COACHING SESSION: UNPACKING RIGORKate, an experienced coach, has been working with an early-career principal, Julia, onconducting observations using the Danielson Framework and engaging in role plays tobuild Julia’s confidence as a leader.During a recent coaching session, aligned to their ongoing work, Kate leveraged feedback that Julia received from her superintendent as the springboard for a rich conversation about rigor.Kate began the session by asking Julia to share her definition of rigor and her vision forhow increased rigor would manifest in the classroom—what would look and sound different? Kate helped Julia clarify for herself what she actually meant by “rigor.” When Juliastruggled to articulate her ideas, Kate asked her to write down some thoughts and thenshare them instead of doing the thinking for her.Once Julia was able to articulate her ideas clearly, Kate had Julia translate her ideas into aset of expectations for teachers. Julia honed in on student engagement and questioning.Kate then asked Julia to practice communicating those expectations. Julia talked aboutdifferentiating very purposefully and finding just the right opportunity to stretch each andevery student. Kate linked this to Julia’s own practice, asking, “How have you used rigor inyour observations of teachers—how are you pushing each one of them?” Kate then askedJulia to role-play a feedback conversation. Kate started out playing the part of the teacherbut later switched roles with Julia in order to model.Next, Kate led Julia in a gap analysis between current and desired states of teacherpractice in the areas of student engagement and questioning. Finally, she pushed Juliato identify what she would need to do differently in terms of her own leadership and herapproach to developing staff in order to effect the changes she desired. Kate’s questionswere intended to produce next steps, including milestones and evidence: “What do taskslook like now?” “What do you want them to look like?” “When would you want to see thisby?” “What are some of the things you need to do first?” After they had spoken specifically about questioning, student engagement, and checking for understanding, Kateasked Julia to consider who she had on staff that could engage in the development workwith her.NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGKate brought the conversation full circle by returning the focus to Julia. “What will you dodifferently as a result of this conversation? What will your next steps be?”

NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG18

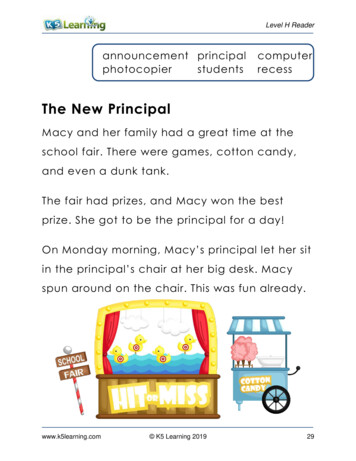

19COACHING ALIGNED TOLEADERSHIP STANDARDSCommitment to a standards-based approach to leadership development is a hallmark of NYCLA’s work. Our coaching work ismapped to a codified definition of leadership.Our leadership standards for principals arecomprised of eight dimensions:1) Personal Behavior2) Resilience3) Communication4) Student Performance5) Situational Problem Solving6) Learning7) Supervision of Staff8) ManagementThese eight leadership dimensions distill themost critical leadership competencies for schoolleaders, and were developed in consultationwith The Wallace Foundation and the stateeducation departments of Delaware, Missouri,and Kentucky. They reflect a thorough reviewand synthesis of principal leadership standardsused nationally, and are grounded in the beliefthat focused work on a subset of clearly definedleadership competencies helps school leaderspromote student success.Many of the districts and states we’ve workedwith across the country around school leadershipcoaching use the LPPW; we typically help themcrosswalk the LPPW against the local schoolleadership performance standards, makingadjustments where necessary. The core idea isthat coaching needs to be anchored in a standards-aligned, contextually relevant competencyframework that identifies what principals need toknow and be able to do to raise achievement forall students. All aspects of the work are alignedto a description of competencies, which involvesknowledge, a set of skills, and dispositions. Theanchoring competencies inform the coachingstrategies that hone the skills of school leaders.The goals of the LPPW are to ground the coaching relationship in concrete skill and knowledgedevelopment; to give coaches and principals acommon language; and to provide a roadmapfor coaching support. The LPPW standards areunique in that they are articulated in very specificbehavioral terms, describing the actions of effec-NYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORGOur leadership standards (or competencies)are codified in a tool called the LeadershipPerformance Planning Worksheet (LPPW). Thetool makes the competencies actionable byarticulating a set of observable behaviors foreach leadership dimension.The LPPW was pilot tested with principals andcoaches in almost 1,000 schools in urban, rural,and suburban school districts across sevenstates. Regardless of geography, demographics,or school setting, the leadership behaviors resonated with pilot users as essential to principalsuccess.

20tive school leaders. These actions include skillssuch as managing ambiguity, solving problems,implementing action plans, and conducting difficult conversations.The LPPW identifies core behaviors criticalto each of the eight leadership dimensions.These core behaviors address the day-to-daychallenges of school leadership.LPPW DIMENSION 3.0:COMMUNICATIONLEADERSHIP DIMENSIONBEHAVIORS THAT MEET THE STANDARDPROGRESS UPDATE3.1 Communicates in waysthat reflect analysis andthe ability to listen Leader’s communication is clear andappropriate for each audience andmatches media with message. Leader understands cultural patternsand adjusts his/her communicationstyle accordingly. Leader attends and responds to subtlenonverbal cues in others. Leader consistently checks for mutualunderstanding. Leader does not avoid difficult issues,he/she deals with then honestly anddirectly by using low-interference dataand providing examples. Leader actively pursues disconfirmingevidence when drawing conclusions.Progress updateO Meets StandardO Approaches Standard3.2 Promotes the successof all students throughconsistently direct communication with studentsand by understandingand responding to theirbroader political, socioeconomic and culturalcontexts. Leader interacts with student body ona consistent basis. Leader models behavior for staffand encourages staff to engage inpurposeful solicitation of studentideas regarding successful classroomapproaches to teaching and learning.O Meets StandardO Approaches StandardNYCLEADERSHIPACADEMY.ORG3.3 Collaborates with StaffO Meets StandardO Approaches StandardArea for Improvement Leaders know all staff members andpublicly acknowledges individualcontributions Leader models, encourages, andreinforces efficacy in individuals toproduce results and persevere evenwhen internal and external difficulties interfere with the achievement ofstrategic goals. Leader generates a sense of urgencyby aligning the energy of others inpursuit of strategic goals.Next StepsLPPW page 4 of 11

21LPPW DIMENSION 3.0:COMMUNICATIONLEADERSHIP DIMENSIONBEHAVIORS THAT MEET THE STANDARDPROGRESS UPDATE3.4 Collaboration with familiesand community Leader establishes interaction withfamilies and community members. Leader develops clear process forgathering and transmitting informationfrom and to families, with awareness ofwhat families in the community do anddo not do have access to, in terms ofelectronic communication. Leader is able to identify all stakeholders involved in the school. Leader’s presentations to parents andcommunity members are organizedand logical, include analysis, and aredelivered in an engaging and dynamicstyle. Leader provide clear, specific responses to questions. Leader accords individuals consistentamount of attention, time, and respect. Leader demo

Leadership Academy's approach to coaching. It is our hope that system leaders, coaches, and principals use the information here to create more sustainable systems for leadership support, ultimately benefiting the students we collectively serve. Sandra J. Stein Former CEO of NYC Leadership Academy July 2015