Transcription

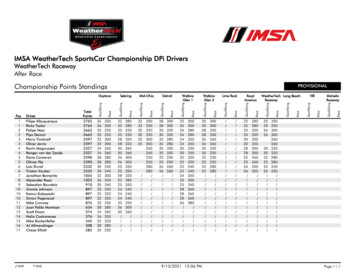

Studies in American Political Development, 21 (Fall 2007), 230–265.Frontlash: Race and theDevelopment of Punitive CrimePolicyVesla M. Weaver, University of Virginia. . . fear in turn seeks repressiveness as a source of safety. [1970]—Ramsey Clark, former Attorney General (1967–1969)I sense there is a tendency to make crime in the streets synonymous with racial threats or the needto control the urban Negro problem. [1968]—Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, sociologist whose doll studies were instrumental in showingthat separate was not equal in Brown v. Board of EducationCivil rights cemented its place on the nationalagenda with the passage of the Civil Rights Actof 1964, fair housing legislation, federal enforcement of school integration, and the outlawing ofdiscriminatory voting mechanisms in the VotingRights Act of 1965. Less recognized but no lessimportant, the Second Reconstruction also witnessed one of the most punitive interventions inUnited States history. The death penalty wasreinstated, felon disenfranchisement statutes fromthe First Reconstruction were revived, and thechain gang returned. State and federal governments revised their criminal codes, effectively abolishing parole, imposing mandatory minimumsentences, and allowing juveniles to be incarceratedin adult prisons. Meanwhile, the Law EnforcementAssistance Act of 1965 gave the federal governmentan altogether new role in crime control; severalsubsequent policies, beginning with the CrimeControl and Safe Streets Act of 1968 and culminating with the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, ‘waron drugs,’ and extension of capital crimes, significantly altered the approach. These and other developments had an exceptional and long-lastingeffect, with imprisonment increasing six-foldbetween 1973 and the turn of the century.1Certain groups felt the burden of these changes1. See Figure 1 in this article, depicting the growth of theprison population and incarceration rate over time.230most acutely. As of the last census, fully half ofthose imprisoned are black and one in threeblack men between ages 20 and 29 are currentlyunder state supervision. Compared to its advancedindustrial counterparts in western Europe, theUnited States imprisons at least five times moreof its citizens per capita.I argue that the punitive policy intervention wasnot merely an exercise in crime fighting; it bothresponded to and moved the agenda on racial equality. In particular, I present the concept of frontlash—the process by which formerly defeated groups maybecome dominant issue entrepreneurs in light ofthe development of a new issue campaign. In thecase of criminal justice, several stinging defeats foropponents of civil rights galvanized a powerfulelite countermovement. Aided by two prominentfocusing events—crime and riots—issue entrepreneurs articulated a problem in a new, ostensiblyunrelated domain—the problem of crime. Thesame actors who had fought vociferously againstcivil rights legislation, defeated, shifted the “locusof attack” by injecting crime onto the agenda.Fusing crime to anxiety about ghetto revolts, racialdisorder—initially defined as a problem of minoritydisenfranchisement—was redefined as a crimeproblem, which helped shift debate from socialreform to punishment. Thus, policies related tocrime were part of a critical episode in race-makingand protracted contest over the political agenda.# 2007 Cambridge University PressISSN 0898-588X/07 15.00

RACE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF PUNITIVE CRIME POLICY 231What the literature usually treats as independenttrajectories—liberalizing civil rights and morerepressive social control in criminal justice—werepart of the same political streams and the actorsand incentives were components in an unfoldingpolitical drama that would alter significantlythe federal government’s role in crime policyand, more importantly, race in post-civil rightsAmerica.First, I elaborate a framework for understandinghow crime came to dominate the domestic agenda.Next, I go deep into the policy changes and thepublic and private debates that surrounded them. Idescribe how the pace and direction of federalaction on crime changed, tracing the movement ofcrime policy through initial federal attention tocrime, characterized by a focus on fairness in thesystem and root causes, and ultimately to the emergence of “law and order” policies. In the process, Ihighlight the possibilities that existed in the earlyperiod and the routes that were not followed. Ianalyze congressional hearings around importantcriminal justice policies, party platforms, campaignmaterial and speeches, oral histories, key votes,commission reports, media and secondary accounts,presidential messages to Congress, media coverage,and government reports, complimenting thesepublic sources with internal documents fromLyndon Johnson’s administration. I focus mainly onthe years from 1958 to 1974, paying closestattention to the years from 1965 to 1972, duringwhich time attention to crime and policy changeburgeoned.The Role of Politics in Crime PolicyTwo scholars of criminal justice recently observed:“Criminologists and sociologists rarely make the political dimension of crime policy a principal concern,and political scientists almost never do.”2 I beginwith the selective accounts that have begun to fillthe vast lacuna of the political science of punishment.Marie Gottschalk’s recent book centralizes the role ofearly developments and crusades against crime inleading to the building of the “carceral state”; sheargues that each of these crime campaigns (and thesocial movements with which they interacted) leftbehind institutional residues which would enablelater developments.3 While race is mentioned, itsinfluence is underwhelming and often completelyoverlooked. In showing how social movements conditioned the latest crime campaign, the civil rights2. Franklin E. Zimring and David T. Johnson, “Public Opinionand the Governance of Punishment in Democratic PoliticalSystems,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and SocialScience 605 (2006): 267.3. Marie Gottschalk, The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics ofMass Incarceration in America (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006).movement is barely mentioned. While Gottschalkably puts the lie to the notion that law and order campaigns were a recent phenomenon, this point comesat the cost of underestimating the genuine distinctiveness and importance of the crime policy changes thatoccurred starting in 1965, which ushered in a trulynew scale of imprisonment. Unlike past episodes,the latest crime campaign launched the UnitedStates to the world record for incarcerating thelargest proportion of its citizens.David Garland’s book also provides a long historical perspective. In this work, social, cultural, andeconomic developments of “late modernity” greatlyweakened the penal-welfare state.4 A complex,all-encompassing set of macrohistorical and societalfactors—including but not limited to womenentering the labor force, modernization of capitalistproduction, demographic changes and suburbanization, changes in family structure and divorce, andtechnological advances in the media (particularlythe rise of television)—together are responsible forboth more crime and more incarceration. Throughthis oversimplification, the primary actor is societyitself and every change that characterized the latterhalf of the twentieth century; in short, the theory isoverdetermined and offers a very loose frameworkfor how social disorganization created insecurityand general anxiety about disorder to the detrimentof laying out more proximate mechanismsbehind policy change and legislative activism oncrime.Jonathan Simon’s recent book, Governing ThroughCrime, refines the generality of Garland’s thesis andis not beset by Gottschalk’s failure to recognize thetrue distinctiveness of the post-1960s crime mobilization. Simon argues that the United States hascreated a new political order and mode of governancethat is structured around crime and the fear of crime;crime has become “a, if not the, defining problem ofgovernment.”5 Governing through crime has becomethe dominant mode—whether in managing crimerisk, valorizing the victim in political discourse, or inusing crime as a legitimate reason for action inother domains. While Simon’s focus is different—the consequences of this reordering and transformation for democracy—his account compellingly highlights the political dimension of crime politics and theways institutions and governance were transformed bythe various “wars on crime.” Using original historicalcounterfactuals, Simon convincingly demonstratesthat crime was the path of least resistance for government intervention and innovation and the crimeproblem actually became a “solution” to the4. David Garland, The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order inContemporary Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).5. Jonathan Simon, Governing Through Crime: How the War onCrime Transformed American Democracy and Created a Culture of Fear(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 13.

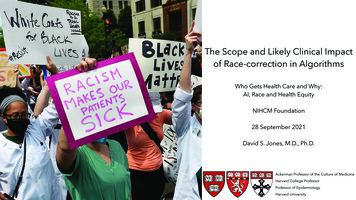

232VESLA M. WEAVERproblem of governance left by the New Deal.Through his account, we see how crime legislationduring the 1960s was not simply legislation but wascritical in the forging of a new governing coalitionand in presenting crime as a priority for government.In his words, “That legislation and the metaphoricmapping of American society it promoted remain, Iwould argue, the dominant interpretive grid onwhich governable America is known and acted uponby government officials at all levels.”6Several scholars have advanced the idea that crimepolicy transcends the instrumental logic of reducingcrime and is better understood as deeply symbolic.The overarching theme in these accounts is thatcrime is a symbol for other societal anxieties.7 Scheingold argues that crime policy is a “product of politicaldecisions rather than moral or functional imperatives.”8 In a similar vein, Morone and Meier arguethat crime and drug policy exist in the category of“morality politics,” or “policies that redistributevalues rather than income.”9 Race is the axiomaticexample. Racial motivations take a central place inthe crime drama, particularly for Katherine Beckett,Bruce Western, and Naomi Murakawa.10 In additionto his economic account of the prison, sociologistBruce Western argues that “the prison boom was apolitical project that arose partly because of risingcrime but also in response to an upheaval in American race relations in the 1960s.”11 Katherine Beckettpresents a similar argument: “In short, the creationand construction of the crime issue in the 1950sand 1960s reflect its political utility to conservativeopponents of social and racial reform.”12 Beckettidentifies a relationship between the initiative ofelites and the media and changes in public opinion.Natalie Murakawa’s research goes even further in theorizing about the connection between crime andrace. She posits a “race-laden electoral connection”in which crime policy is developed in a context6. Ibid., 8.7. Michael Tonry, Malign Neglect—Race, Crime, and Punishmentin America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); Stuart Hallet al., Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order(London: Macmillan, 1978); Garland, Culture of Control; Stuart A.Scheingold, The Politics of Law and Order: Street Crime and PublicPolicy (New York: Longman, 1984).8. Scheingold, Politics of Law and Order, 5.9. Kenneth J. Meier, The Politics of Sin: Drugs, Alcohol, and PublicPolicy (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1994); James A. Morone, HellfireNation: The Politics of Sin in American History (New Haven, CT: YaleUniversity Press, 2003), 455– 77.10. Katherine Beckett, Making Crime Pay: Law and Order in Contemporary American Politics (New York: Oxford University Press,1997); Bruce Western, Bruce, Punishment and Inequality in AmericanDemocracy (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006); Loic Wacquant, “The New ‘Peculiar Institution’: On the Prison as SurrogateGhetto,” Theoretical Criminology 4 (2000): 377– 89; Naomi Murakawa,“Electing to Punish: Congress, Race, and the American CriminalJustice State” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2005).11. Western, Punishment and Inequality, 5.12. Beckett, Making Crime Pay, 28–29.where parties and legislators have incentives toproffer racial framings of the crime problem, andbecause the costs of the policies are “racially concentrated,” there are few checks on the “punitive biddingwars” that result. Murakawa’s account is a unique contribution of how racial power in the U.S. intersectedwith electoral incentives to create a durable punitiveframework. Unlike other accounts, she presents anaggressive account of why crime policy is tied torace and in locating the importance of how crimewas framed in the 1960s, providing a rich descriptionof problem framings and party convergence.While Murakawa, Beckett, and Western all considerthe civil rights era an important moment in the development of punitive crime policy to different degreesand make bold claims about the racially inflectedmotivations of elites, why that is the case is notaltogether clear and there is a mismatch betweenthe scale of their claims and the research to supportit, a mix of thick descriptive anecdotes and quantitative analyses that skip over the process of change.Their research contains a similar view of themanner in which crime was framed in congressionallegislation during 1960s. Indeed there are symmetriesbetween our accounts and the emphasis we place oncritical factors—changing crime discourse, theimportance of elites, and the emboldened federalrole. The key difference is that while they assert a connection of civil rights agenda to crime, that connection is underspecified.All pay attention to this historical moment and tohow legislative incentives are molded by race, yetthe question of “why the 1960s?” remains undertheorized. Why did race come to matter when it did? Forinstance, Murakawa hypothesizes that “mandatoryminimum statutes will increase with the waning political power of civil rights agendas”; however, her quantitative analysis, while quite original, does not bring usnear that conclusion, finding only that mandatoryminimums are related to the electoral cycle. Simonasserts that civil rights was a very probable issue for“recasting New Deal governance” but that it was“stymied easily when the crime agenda decisivelysprinted ahead,” without considering the possibilitythat these two developments were not merelycoincidental.13I contend that these accounts are important firststeps in theorizing the role of race in crime policymaking, and their ambiguity is the motivation for adeeper investigation. These accounts highlight thepolitical dimension of crime policy and the role ofrace, but they hesitate in fully articulating just howand why racial conflict came to matter in shapingcriminal justice, at which part of the policy processit came to matter, and the particular mechanismsthat are driving the outcomes; without an adequate13. Simon, Governing Through Crime, 28.

RACE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF PUNITIVE CRIME POLICY 233theory, they fall short of empirically testing theirinstincts. This article continues in their path by deepening the mechanisms in their accounts and bringing into historical conversation the path of criminaljustice and civil rights. Rather than being seen as critical of these accounts though, I use them as steppingstones to further our understanding of the politicaldevelopment of crime policy. I pause longer at the historical moment they identify, and, in so doing, find amore complex and nuanced developmental process.The idea that conservatives used race and crime instrategic ways is neither novel nor unique to the criminal justice literature; research on the civil rights eraoft mentions law and order and Nixon’s southernstrategy. Although not specifically concerned withexplaining criminal justice, several historical accountsand one important recent work acknowledge the linkages between social change in the 1960s and repressive responses.14 In his historical account of “law andorder,” Michael Flamm centers race and civil rights inthe analysis: “For conservatives, black crime wouldbecome the means by which to mount a flank attackon the civil rights movement when it was toopopular to assault directly.”15 Other scholars haveshown how crime has become a racial codeword, strategically employed by vote-seeking politicians.16 Thestrong association of crime with blacks leads onescholar to note that, “later discourse about crime isdiscourse about race.”17 However, within politicalscience, racialized framings are treated as simply arhetorical appeal without lasting policy implications.One must look to other policy domains, particularlywelfare, for research on how race has affected thedevelopment and politics around policies.1814. Michael W. Flamm, Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest,and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005); Thomas E. Cronin, Tania Z. Cronin, and MichaelF. Milakovich, U.S. v. Crime in the Streets (Bloomington, IN: Universityof Indiana Press, 1981); Richard M. Scammon and Ben J. Wattenberg, The Real Majority (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1970);Malcolm M. Feeley and Austin D. Sarat, The Policy Dilemma: FederalCrime Policy and the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration,1968– 1978 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1980).15. Flamm, Law and Order, 22. Also see Steven E. Barkan, Protesters on Trial: Criminal Justice in the Southern Civil Rights and VietnamAntiwar Movements (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press,1985); James W. Button, Black Violence: Political Impact of the 1960sRiots (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978); Cronin,Cronin, and Milakovich, U.S. v. Crime in the Streets.16. Tali Mendelberg, The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, ImplicitMessages, and the Norm of Equality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).17. Melissa Hickman Barlow, “Race and the Problem of Crimein Time and Newsweek Cover Stories, 1946 –1995,” Social Justice 25(1998): 178; emphasis in original.18. Martin Gilens, Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, andthe Politics of Antipoverty Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1999); Robert C. Lieberman, Shifting the Color Line: Race and theAmerican Welfare State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,1998); Jill S. Quadagno, The Color of Welfare: How Racism Underminedthe War on Poverty (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); IraKatznelson, When Affirmative Action was White: An Untold History ofThe remainder of the article investigates theprocess of problem definition and the considerations that went into policy change. But the mostobvious explanation for why crime came to thecenter of the agenda is that crime got much worse.The accounts discussed earlier share a commonfeature: they dismiss crime outright as a potentialexplanation, but the grounds on which they refutecrime are shaky. Most base their claims on theaxiom of criminological research—that there is virtually no empirical correlation between crime trajectories and incarceration or between the incidence ofcrime and public concern with crime.19 While Iagree with this thesis, I propose a different explanation for what motivated policy changes. Proponents of the crime-is-not-cause congregation raise apanoply of illustrative evidence. Incarcerationsteadily increased during the 1970s, 1980s, and1990s, as the argument goes, regardless of whethercrime was rising or falling. Crime was rising longbefore incarceration started to increase. Moreover,according to this argument, variation in crimeamong the states does not explain variation instate imprisonment. In showing the crime rate tobe largely orthogonal, extant studies have focusedon the crime-incarceration and public opinioncrime linkage, not crime-policy change. However,studies where incarceration is not the dependentvariable have found an effect of crime; forexample, the national budget and congressionalactivity are responsive to changes in crime.20 Otheraccounts not only challenge the influence ofcrime, but reject the rise in crime in the 1960saltogether. Evidence for this bold claim is questionable, usually resting on the fact that crime increasedsteadily after WWII so that the increase duringthe 1960s continued an upward pattern that wasnot distinct from the 1950s.21While it is true that criminal justice legislation hasnot responded mechanically with fluctuations incrime rates, in their eagerness to dismiss crime, theyhave thrown the baby out with the bathwater. TheRacial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: W.W.Norton & Company, 2005); Ange-Marie Hancock, The Politics ofDisgust: the Public Identity of the Welfare Queen (New York:New York University Press, 2004).19. Sean Nicholson-Crotty and Kenneth J. Meier, “Crime andPunishment: The Politics of Federal Criminal Justice Sanctions,”Political Research Quarterly 56 (2003): 119– 26.20. Greg A. Caldeira and Andrew T. Cowart, “Budgets, Institutions, and Change: Criminal Justice Policy in America,” AmericanJournal of Political Science 24 (1980): 413–38; Willard M. Oliver, “ThePower to Persuade: Presidential Influence Over Congress on CrimeControl Policy,” Criminal Justice Review 28 (2003): 113– 32; WillardM. Oliver and David E. Barlow, “Following the Leader? PresidentialInfluence Over Congress in the Passage of Federal Crime ControlPolicy,” Criminal Justice Policy Review 16 (2005): 267–86.21. Malcolm M. Feeley, “Crime, social order and the rise ofneo-Conservative politics,” Theoretical Criminology 7 (2003): 111– 30.

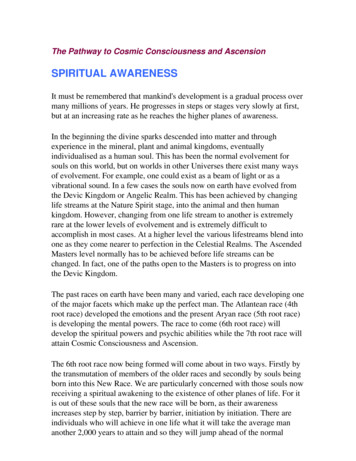

234VESLA M. WEAVERFig. 1. Imprisonment in the United States, 1925 – 2002.Source: Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Online (www.albany.edu/sourcebook/pdf/t6282004.pdf), Table 6.28.2004: “Number andrate (per 100,000 resident population in each group) of sentenced prisoners under jurisdiction of State and Federal correctional authoritieson December 31. By sex, United States, 1925 –2004.”Note: Data does not include local jail population.above points are useful but not to conclude that crimeis wholly inconsequential; a more fruitful discussion isto understand why crime came to be politicized in the1960s and not before and unearth the full quilt ofmotivations embodied in its being elevated to a thestatus of major national problem. In other words,in refusing to attribute any role to crime, thesestudies are forced into the same zero-sum frameworkthey attempt to challenge. As Figure 2 demonstrates,crime rose steeply in the 1960s, particularly propertybased offenses. Indeed, as I discuss later, crimestatistics were by far not the objective measure ofactual crime and were often tweaked. So it is possiblethat the crime figures were untrustworthy. Settingaside the accuracy problems in gauging crime,crime can matter in a host of other ways and theperception of a crime wave can be even moreimportant than reality. Media can facilitate a fictitious crime rise through biased coverage or highlyvisible crimes, politicians can signal the importanceof the problem by alluding to crime in their campaigns, and the resolution or ascendance of otherissues can give disproportionate influence to theissue of crime.I agree that crime is not the primary explanation;however, I part company with the accounts thatargue that its tenuous relationship to punishment issimply because it has no link to incarceration orthat the crime problem was overestimated. Crimedid rise quite substantially and the homicide rate, byfar the most unbiased measure of violent crime, sawa precipitous rise. Demographic changes and technical innovations in crime reporting ensured that evenwithout society becoming more violent, crime wouldhave still been a serious problem. Mine is a differentargument—that crime is a partial explanation thatcannot fully explain the ways in which the problemwas addressed. I do not dismiss crime. Much likethe actual presence of Communist affiliates in theanticommunist frontlash against unions and NewDeal policies—a case I discuss below—crime was arising problem in the United States; however, it alsooperated as a symbol for other motivations. The question is not just whether crime was a rising problem,but what factors best explain the way it was definedand why understandings and approaches changedand subsequently, why the policies to deal withcrime departed course. Crime might have been

RACE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF PUNITIVE CRIME POLICY 235Fig. 2. The Crime Rate Overtime by Offense Type, 1960 – 2001.Source: Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Online (www.albany.edu/sourcebook/1995/wk1/t3103.wk1), Table 3.103: “Estimatednumber and rate (per 100,000 inhabitants) of offenses known to police, by offense, United States, 1960–2001.” Based on the UniformCrime Reports.rising, but the primary catalyst was to be found elsewhere. Without elite goals and shift in power, crimeand violence were merely objective conditions. Deepinvestigation into how the issue was framed and negotiated in the political process provides crucial insightsinto when and under what conditions crime came tobe an urgent social problem.Several factors cast a doubtful shadow on the intrinsicvalue and singular role of crime in shaping the agenda.First, crime was rising for almost a decade before it wasdefined as a problem in the machinery of politics, whichserves as an important reminder of Blumer’s point thatsocial problems are attached to processes of collectivedefinition.22 Second, crime can be addressed in avariety of ways—from more prevention to more punishment. The simplistic assumption that increases in crimeare behind changes that led to increasing prison populations ignores the politicization of the issue, how targetgroups were socially constructed, and elite incentivesand agency. A crime boom might explain heightenedattention to the issue but only goes part of the way in22. Herbert Blumer, “Social Problems as Collective Behavior,”Social Problems 18 (1971): 298–306.explaining the punitive path and expansion in federalauthority. Crime is not divorced from other factorsthat affect its politicization; only a naı̈ve observerwould conclude that other crime campaigns weresolely about crime. Would one be comfortable assuming, to draw on a few examples, that Prohibition wasonly about a rise in alcohol-induced violence, thatconcern over immigrant crime in the 1920s hadnothing to do with anti-immigrant sentiment, or thatthe scare over cocaine-addicted blacks during the1920s (or the modern war on drugs) was singularlymotivated? Conversely, the historical record is repletewith cases when crime rose but was not followed bypunitive legislation or a national campaign, includingrising crime in the post WWII period.So while crime does figure in the story, it is not themain character. Crime did rise and it does matter, buttwo additional factors suggest that it was not the solemotivation: (1) criminals began to receive longer sentences for the same crimes in the United States (2)the risk of incarceration increased steeply.23 Therefore, somewhere in the process of policy adoption,23. Western, Punishment and Inequality.

236VESLA M. WEAVERlegislators decided to punish the same offenses more.I will devote much of the following to exploring themotivations for policy. Mine is an argument notabout whether crime rose, but on how it came to bedefined and politicized.To cover the expanse of literature on why punitiveness has become gospel, it would take an encyclopedic treatment, which is not my purpose. This articleseeks not to prove existing accounts wrong, butrather to expand them both in theoretical andempirical depth. To do that requires the articulationof a theory that does not isolate crime policy fromthe political agenda or from other policy domains.In so doing, it becomes clear that existing accountsare not so much wrong as seriously incomplete.Toward a New TheoryTo explain this developmental process in criminaljustice, I advance the notion of frontlash, or theprocess by which losers in a conflict become the architects of a new program, manipulating the issue spaceand altering the dimension of the conflict in an effortto regain their command of the agenda. Frontlashhinges on the presence of winners and losers of arecent political conflict. In the aftermath, newnorms are born and institutionalized, which “involvesa shrinkage and rejection of positions that previouslyhad been deemed acceptable.”24 But despite thescore being settled on one conflict, losers do not disappear once defeated, nor do their ideologies.Rather, the losers seek to “preserve but also perpetuate the distribution of power emanating from thosesalient [past] political conflicts,” rendering theresults of the past conflict fundamentally unstable.25The dissatisfied parties seek openings to mobilize anew issue, alter the dimension of the conflict, or, inthe terminology of social movement theorists, “shiftthe locus of attack.”26 Rather than defend the status24. R. Kent Weaver, Ending Welfare as We Know It (Washington,DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2000), 37.25. Edward G. Carmines and James A. Stimson, Issue Evolution:Race and the Transformation of American Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 6. See also Frank R. Baumgartnerand Bryan D. Jones, Agendas and Instability in American Politics(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 6: “So long as thepossibility exists of mobilizing the previously indifferent throughthe redefinition of issues, no system based on the shared preferences of the interested is safe.” And William H. Riker, Agenda Formation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1993): “Thepolitical forces are the interests of politicians: previous winners,of course, seek to maintain the status quo of issues on which theyhave won, while previous losers seek to bring up new issues onwhich they can win.”26. E. E. Schaattschneider, The Semisovereign People

The overarching theme in these accounts is that crime is a symbol forother societal anxieties.7 Schein-gold arguesthat crime policy is a "product of political decisions rather than moral or functional impera-tives."8 In a similar vein, Morone and Meier argue that crime and drug policy exist in the category of