Transcription

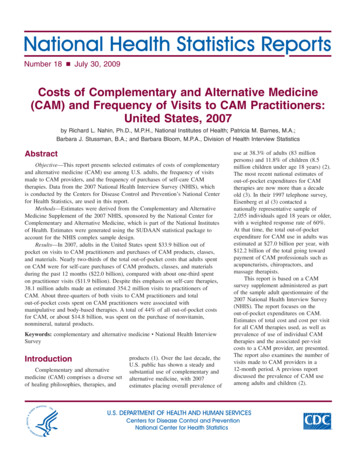

Number 343 May 27, 2004Complementary and Alternative MedicineUse Among Adults: United States, 2002Patricia M. Barnes, M.A., and Eve Powell-Griner, Ph.D., Division of Health Interview Statistics; andKim McFann, Ph.D., and Richard L. Nahin, Ph.D., M.P.H., National Center for Complementary andAlternative Medicine, National Institutes of HealthAbstractIntroductionObjective—This report presents selected estimates of complementary andalternative medicine (CAM) use among U.S. adults, using data from the 2002National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), conducted by the Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).Methods—Data for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population werecollected using computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). This report is basedon 31,044 interviews of adults age 18 years and over. Statistics shown in this reportwere age adjusted to the year 2000 U.S. standard population.Results—Sixty-two percent of adults used some form of CAM therapy duringthe past 12 months when the definition of CAM therapy included prayer specificallyfor health reasons. When prayer specifically for health reasons was excluded fromthe definition, 36% of adults used some form of CAM therapy during the past 12months. The 10 most commonly used CAM therapies during the past 12 monthswere use of prayer specifically for one’s own health (43.0%), prayer by others forone’s own health (24.4%), natural products (18.9%), deep breathing exercises(11.6%), participation in prayer group for one’s own health (9.6%), meditation(7.6%), chiropractic care (7.5%), yoga (5.1%), massage (5.0%), and diet-basedtherapies (3.5%). Use of CAM varies by sex, race, geographic region, healthinsurance status, use of cigarettes or alcohol, and hospitalization. CAM was mostoften used to treat back pain or back problems, head or chest colds, neck pain orneck problems, joint pain or stiffness, and anxiety or depression. Adults age 18years or over who used CAM were more likely to do so because they believed thatCAM combined with conventional medical treatments would help (54.9%) and/orthey thought it would be interesting to try (50.1%). Most adults who have ever usedCAM have used it within the past 12 months, although there is variation by CAMtherapy.Complementary and alternativemedicine (CAM) is a group of diversemedical and health care systems,therapies, and products that are notpresently considered to be part ofconventional medicine. The U.S.public’s use of CAM increasedsubstantially during the 1990s (1–11).This high rate of use translates intolarge out-of-pocket expenditures onCAM. It has been estimated that theU.S. public spent between 36 billionand 47 billion on CAM therapies in1997 (5). Of this amount, between 12.2billion and 19.6 billion was paidout-of-pocket for the services ofprofessional CAM health care providerssuch as chiropractors, acupuncturists,and massage therapists. These fees aremore than the U.S. public paid out-ofpocket for all hospitalizations in 1997and about half that paid for all out-ofpocket physician services (12).Explanations for this growth inCAM use have been proposed, includingmarketing forces, availability ofinformation on the Internet, the desire ofpatients to be actively involved withmedical decision making, anddissatisfaction with conventionalKeywords: complementary and alternative medicine c National Health InterviewSurveyU.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICESCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Health Statistics

2Advance Data No. 343 May 27, 2004(western) medicine (13). Thisdissatisfaction may be related to theinability of conventional medicine toadequately treat many chronic diseasesand their symptoms such as debilitatingpain (1). Rates of CAM use are alsoexceptionally high among individualswith life threatening illnesses such ascancer (14) or HIV (15). It appears thatthe majority of people use CAM as acomplement to conventional medicine,not as an alternative (1,3,5).As used by the U.S. public, CAMconsists of many heterogeneous systemsof medicine as well as numerousstand-alone therapies (16). Severalsystems of CAM are practiced as part ofthe health care system in U.S.immigrants’ countries of origin (17). Forexample, Ayurveda is practiced in Indiaat a national level within the Federalhealth system. Traditional Chinesemedicine, which includes acupuncture,acupressure, herbal medicine, tai chi,and qi gong, is often practiced in thesame hospitals or clinics as conventionalmedicine in China. Kampo, the systemof traditional herbal medicine in Japan,is covered by the national healthinsurance plan and is practiced by manymedical doctors (18). Immigrants fromthese and other countries of origin maycontinue to rely on CAM as part of theirmedical treatment in the United Stateseven as they seek care fromconventional health care providers.Some of these systems may eventuallyprove to be low cost health care optionsfor use by the U.S. public.Despite the diverse ways in whichthese systems and therapies developed,they appear to have severalcharacteristics in common: the use ofcomplex interventions, often involvingthe administration of many medicationsor medicinal substances at the sametime; individualized diagnosis andtreatment of patients; an emphasis onmaximizing the body’s inherent healingability; and treatment of the ‘‘whole’’person by addressing their physical,mental, and spiritual attributes ratherthan focusing on a specific pathogenicprocess as emphasized in conventionalmedicine (19).Notwithstanding the growingscientific evidence that some CAMtherapies may be effective for specificconditions (20,21), the public’s wide useof many untested CAM therapies mighthave unanticipated negativeconsequences. For example, the U.S.Department of Health and HumanServices banned the sale of the herbalsupplement ephedra in 2003 afterconcluding that the risks associated withuse of this product by the general publicgreatly outweighed any potential benefit(22). It has been found that other herbalproducts interact or interfere with thenormal pharmacology of somepharmaceutical drugs with potentiallyfatal consequences (23). CAM usersoften do not share information aboutsuch use with their conventional healthcare providers (5), thereby increasingthe possibility of serious interactions.Even when conventional health careproviders are aware that their patientsare taking herbal products, seriousinteractions could result if providers areunfamiliar with the scientific literatureon CAM. Understanding the prevalenceand reasons for CAM use is a first steptoward improving communicationbetween health care providers and theirpatients.This report is based on a CAMsupplement that was administered aspart of the sample adult questionnaire ofthe 2002 NHIS. The report focuses onwho uses CAM, what is used, and whyit is used. It also examines therelationship between the use of CAMand the use of conventional medicalpractices. In particular, the reportexamines the relationship of CAM useand demographic and health behaviorsamong groups not previously studied indetail, including race and ethnic groups,the economically disadvantaged, and theelderly. The 2002 NHIS includedquestions that asked respondents abouttheir use (ever and during the past 12months) of 27 different CAM therapies.This report defines CAM broadly byincluding therapies or practices that maynot be considered CAM, such as prayerspecifically for health purposes andhigh-dose vitamin therapy, and examinesthe use of these practices in specificpopulations.MethodsData sourceThe statistics shown in this reportare based on data from the AlternativeHealth/Complementary and AlternativeMedicine supplement, the Sample AdultCore component, and the Family Corecomponent of the 2002 NHIS (24). TheNHIS, one of the major data collectionsystems of CDC’s NCHS, is a survey ofa nationally representative sample of thecivilian noninstitutionalized householdpopulation of the United States. Basichealth and demographic informationwere collected on all householdmembers. Adults present at the time ofthe interview are asked to respond forthemselves. Proxy responses areaccepted for adults not present at thetime of the interview and for children.Additional information is collected onone randomly selected adult age 18years or over (sample adult) and onerandomly selected child age 0–17 years(sample child) per family. Informationon the sample adult is self-reportedexcept in rare cases when the sampleadult is physically or mentally incapableof responding, and information on thesample child is collected from an adultfamily member who is knowledgeableabout the child’s health.The Alternative Health/Complementary and AlternativeMedicine supplemental questionnaireincluded questions on 27 types of CAMtherapies commonly used in the UnitedStates (table 1). These 27 CAMtherapies included 10 types of providerbased CAM therapies (e.g., acupuncture,chiropractic care, folk medicine), as wellas 17 other CAM therapies for whichthe services of a provider are notnecessary (e.g., natural products, specialdiets, megavitamin therapy). The CAMsupplement, unlike earlier surveys,includes specific types of CAM dietssuch as Atkins, Macrobiotic, Ornish,Pritikin, and Zone; a comprehensiverange of mind-body therapies, includingbiofeedback, deep breathing techniques,guided imagery, hypnosis, progressiverelaxation, qi gong, tai chi, and yoga;

Advance Data No. 343 May 27, 2004and the use of prayer for healthpurposes. Inclusion and development ofthe 2002 supplement was supported, inpart, by the National Center forComplementary and AlternativeMedicine (NCCAM), National Institutesof Health (NIH).Statistical analysisThis report is based on data from31,044 completed interviews withsample adults age 18 years and over,representing a conditional sample adultresponse rate of 84.4% and a finalsample adult response rate of 74.3%.Procedures used in calculating responserates are described in detail in‘‘Appendix I’’ of the Survey Descriptionof the NHIS data files (24). Because theCAM questions were administered aspart of the Sample Adult questionnaireand only about 1.4% of the sampleadults did not answer any questions inthe CAM supplement, a separateresponse rate for the CAM questionswas not calculated.All estimates (percents andfrequencies) and associated standarderrors shown in this report weregenerated using SUDAAN, a softwarepackage designed to account for acomplex sample design such as thatused by the NHIS (25). All estimateswere weighted using the sample adultrecord weight, to represent the U.S.civilian noninstitutionalized populationage 18 years and over.Most estimates presented in thisreport were age adjusted to the year2000 U.S. standard population age 18years and over (26,27). The SUDAANprocedure PROC DESCRIPT was usedto produce age-adjusted percentages andtheir standard errors. Age adjustmentwas used to allow comparison ofvarious sociodemographic subgroupsthat have different age structures. Theestimates found in this report were ageadjusted using the age groups 18–24years, 25–44 years, 45–64 years, and 65years and over, unless otherwise noted.(See ‘‘Technical Notes’’ for details.)Age-adjusted estimates werecompared using two-tailed statisticaltests at the 0.05 level. No adjustmentswere made for multiple comparisons.Terms such as ‘‘greater than’’ and ‘‘lessthan’’ indicate a statistically significantdifference. Terms such as ‘‘similar’’ or‘‘no difference’’ indicate that thestatistics being compared were notsignificantly different. Lack of commentregarding the difference between anytwo statistics does not mean that thedifference was tested and found to benot significant.Most statistics presented in thisreport can be replicated using NHISpublic use data files and accompanyingdocumentation available fordownloading from the NCHS Web siteat: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.Variables identifying metropolitanstatistical area (MSA), urban/ruralresidence, and State, which was used tocreate the category ‘‘Pacific States,’’ arenot included in the public use data filesto protect respondent confidentiality.Therefore, corresponding estimatescannot be replicated. Many of thereferences cited in this report are alsoavailable via the NCHS Web site at:http://www.cdc.gov/nchs.3For therapies used during the past 12months, respondents were asked moredetailed questions such as the healthproblem or condition being treated withthe therapy, the reason(s) for choosingthe therapy, whether the costs of thetherapy were covered by insurance, theirsatisfaction with the treatment, andwhether any of their conventionalmedical professionals knew they wereusing the therapy.The CAM questions have severallimitations. First, they are dependentupon respondents’ knowledge of CAMtherapies and/or their willingness toreport use accurately. Secondly, thecollection of CAM data at a single pointin time results in an inability to produceconsecutive annual estimates for CAMuse so that changes can not be trackedover time, and it reduces the ability toproduce reliable estimates of CAM usefor small population subgroups as thiswould require a larger sample and/ormore than 1 year of data.ResultsStrengths and limitations of thedataA major strength of the data oncomplementary and alternative medicinein the NHIS is that they were collectedfor a nationally representative sample ofU.S. adults, allowing estimation ofCAM use for a wide variety ofpopulation subgroups. The large samplesize also facilitates investigation of theassociation between CAM and a widerange of other self-reported healthcharacteristics included in the NHISsuch as health behaviors, chronic healthconditions, injury episodes, access tomedical care, and health insurancecoverage.The CAM data collected in the2002 NHIS are a significantimprovement over the CAM datacollected in the 1999 NHIS. The 1999NHIS included only one question thatasked respondents if they had used(during the past 12 months) any o

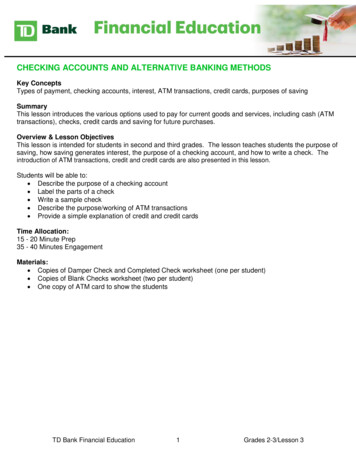

CAM. It has been estimated that the U.S. public spent between 36 billion and 47 billion on CAM therapies in 1997 (5). Of this amount, between 12.2 billion and 19.6 billion was paid out-of-pocket for the services of professional CAM health care providers such as chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. These fees are