Transcription

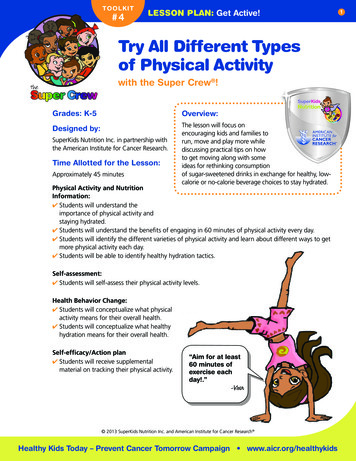

European Journal of Sport Science, vol. 2, issue 4Physical Activity Counseling / 1 2002 by Human Kinetics Publishers and the European College of Sport SciencePhysical Activity Counseling: Assessmentof Physical Activity By QuestionnaireIngrid Frey and Aloys BergRegular physical activity is regarded as an important component of a healthylifestyle. Nevertheless, most adults remain essentially sedentary. Counselingby healthcare providers has the potential to increase physical activity in sedentary individuals. For effective counseling, healthcare professionals will needinformation on current recommendations on physical activity, and on the client’scurrent level of physical activity and motivational readiness for change. Astandardized questionnaire can be a helpful tool to assess physical activitylevels. Administered by interview, the questionnaire will facilitate documentation and analysis of the client’s physical activity patterns and will also provideinformation on the individual stage of motivational readiness for change. According to information derived from the questionnaire, appropriate interventions can be selected.Key Words: physical activity, counseling, recommendations, questionnaireKey Points:1. Physical activity counseling by health care professionals is expected to promotephysical active lifestyle in sedentary individuals.2. Effective counseling will need information on current recommendations on physical activity, on individual’s activity patterns and on the individual’s stage of motivational readiness for change.3. Assessment of physical activity by questionnaire can support counseling in manyrespects.Regular physical activity is regarded as an important component of a healthy lifestyle.New scientific evidence links regular physical activity to a wide array of physicaland mental health benefits (8). Despite this evidence, most adults remain essentiallysedentary. To promote a physically active lifestyle, especially among inactive members of the population, effective interventions are needed. Evidence is accumulatingthat behavioral-based physical activity intervention can be effective (4, 11). In thiscontext, physical activity counseling by the primary care physician seems to be apromising approach. Some studies demonstrated that physician counseling wasassociated with a (short-term) increase in patients’ physical activity levels (3, 16). Itis possible that counseling from a healthcare professional is salient to patientsbecause of perceived physician credibility and authority.The authors are with the Department of Prevention, Rehabilitation and SportsMedicine in the Center of Internal Medicine at the University of Freiburg, Hugstetter Str. 55,D-79183 Freiburg, Germany.1

2 / Frey and BergFigure 1 — Factors determining physical activity counseling.For effective counseling, healthcare professionals will need the followingessential information: profound knowledge of current recommendations on physical activity, detailed information on the participant’s current level of physical activity, and information on the participant’s individual stage of motivational readinessfor change (Figure 1).Current Recommendations on Physical ActivityTo encourage increased participation in physical activity among the general population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College ofSports Medicine issued a public health recommendation on the types and amountsof physical activity needed for health promotion and disease prevention (14): “Every American adult should accumulate 30 minutes of moderate intensity physicalactivity over the course of most, preferably all days of the week”. (This approach isconsistent with recommendations in the NIH consensus report on physical activityand health; see 17.) According to this recommendation, the total daily energy expenditure should be expanded to approximately 2 kcal/kg/d (14 kcal/kg/w).There are different ways to meet this recommendation, including a “moderateactivity” approach and a “vigorous exercise” approach (or a combination of thetwo). The moderate approach encourages fitting more physical activity into one’sdaily routine by taking walks, climbing stairs, and engaging in more physicallyactive leisure time. Multiple episodes of moderate intensity physical activity can beaccumulated in sessions of at least 10 min to reach the total of 30 min a day (7, 12).The vigorous exercise approach involves more formal exercise modes. An increasein total energy expenditure of at least 14 kcal/kg/w can be accomplished by performing exercise three times a week for 30–45 min per session at an intensity of 60–70%of maximal oxygen uptake.

Physical Activity Counseling / 3The health benefits gained from increased physical activity depend on theinitial activity level. Sedentary individuals are expected to benefit most from increasing their activity to the recommended level. People who already meet the basicrecommendation are also likely to derive some additional health and fitness benefitsfrom becoming more physical active (9). Epidemiological research has shown thatmaximum health benefits will be met when an energy expenditure of 4–7 kcal/kg/d(30–50 kcal/kg/w) is reached through increased engagement in everyday activities,recreational activities, and sports (10, 13).Assessment of Physical ActivityKnowledge of the participant’s current level of physical activity is essential in everycounseling session. This raises the question of how physical activity should beassessed. Valid and appropriate measurement of physical activity is a challengingtask, because physical activity is a highly variable component and is comprised ofactivities of daily living, sports and leisure, and occupational activities. In practice,standardized questionnaires can be very helpful in documenting and analyzingphysical activity levels. If one wants to compare individual activity levels with thecurrent recommendations on physical activity, the applied questionnaire has to askabout everyday activities as well as formal exercise modes and should also allowestimation of energy expenditure. The previously published original, as well as themodified (shortened) version of the Freiburger Questionnaire on Physical Activity,meet these criteria (5, 6).The shortened version of the questionnaire includes eight questions. The firstquestion asks for occupational physical activity (rating: mostly sitting, moderatemovement, or intensive movement). The following questions focus on physicalactivities during leisure time (e.g., habitual walking and cycling, gardening, stairclimbing, recreational activities and sports). Participants are asked to report theamount of time spent in the different activities over the past 7 days (everydayactivities), respectively, and the past month (sport and recreational activities). Subsequent to the documentation of the physical activities, data can be analyzed andcompared with the recommended physical activity goals.As mentioned above, physical activity goals often are expressed as total energy expenditure per day or week. An estimate of energy expenditure can be derivedby multiplying hours of reported activity by the average intensity (expressed inMET). One MET represents the metabolic rate of an individual at rest (approximately 3.5 ml O2/kg/min, or 1 kcal/kg/h). Energy requirements for specific physicalactivities can be taken from widely available and comprehensive lists (1, 2).Our shortened questionnaire provides a table that facilitates the estimation ofenergy expenditure. In this table, energy requirements (MET) correspond to physical activities listed in the questionnaire. Knowing the time spent in the specificactivity, one can easily determine the appropriate energy expenditure (expressed inMET-hours per week). Total weekly energy expenditure can be calculated by summating all MET-hours per week. These results can then be compared with currentrecommendations for physical activity, and individual activity patterns can be rated.To facilitate the rating of individual activity patterns, the Freiburger questionnaire provides a score. With this score, the participant’s current level of activity canbe rated as: not active enough ( 15 MET-h per week), meets the basic goal according

4 / Frey and Bergto public health recommendation for physical activity (15–30 MET-h per week),and satisfactorily active ( 30 MET-h per week).Analyzing physical activity patterns also provides insight into the individualstage of motivational readiness for change, which in turn helps to develop appropriate interventions.Individual Stage of Motivational Readiness for ChangeThe transtheoretical model describes behavior change as a process running throughdifferent stages (15). These stages (of motivational readiness for change) are:precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Each stagerequires specific intervention techniques.Physical activity precontemplation means that the individual is not interestedin becoming more active. Precontemplators will profit from talking about advantages and disadvantages of being physically active. The aim of the counseling is toraise the client’s awareness of the problem and to acknowledge the need for action.Contemplators intend to become physically active; however, they lack precise perceptions of how to achieve this. In this case, counseling should focus on reflectingparticipant motivation and discussing factors that could inhibit or promote readiness for change. The aim of the counseling is to emphasize the personal benefit ofbeing physically active and to increase motivation. In the stage of preparation,individuals are occasionally, but not regularly, physically active. Individuals mayneed encouragement to put plans into practice—for example, by defining realisticgoals, planning, self-monitoring, and self-reinforcement. The aim is to support thetransfer of ideas into one’s everyday routines. Individuals in the stage of action areregularly active but not sure that their behavior will be consistent. Within this group,focus should be shifted to relapse prevention (e.g., social support, provision ofcoping strategies). Being in the stage of maintenance means that one is regularlyphysically active and that physical activity is part of the individual’s lifestyle.ConclusionEffective physical activity counseling should be targeted at different personal factors including cognitions, emotions, and self-regulatory skills. The implementationof a suitable questionnaire in physical activity counseling can be very helpful.Administered by interview, the questionnaire will help participants to reflect ontheir own physical activity patterns. This will raise the client’s awareness of his orher present level of physical activity and possible need for change. The detailedassessment will lead to profound knowledge of the participant’s current level ofphysical activity and provide information about the participant’s stage of motivational readiness. This essential information is crucial for devising appropriate intervention strategies.As the process of changing behavior patterns takes time and relapses mayoccur at different stages, it is unlikely that one session of counseling will lead tolong-lasting success. Regular review at certain intervals is therefore important.Repeated application of a standardized questionnaire facilitates the comparison ofactivity patterns. Changes in behavior become apparent and self-monitoring is supported, which has an impact on motivation.

Physical Activity Counseling / 5Physical activity counseling supported by questionnaire is a promisingapproach to enhance participants’ ability to integrate physical activity into theirdaily life.References1. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Jr., Montoye HJ, Sallis, JF, PaffenbargerRS, Jr. 1993. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of humanphysical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25:71-80.2. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL,Bassett DR, Jr., Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Jr., Leon AS. 2000. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med SciSports Exerc 32(9 Suppl.):S498-S504.3. Calfas KJ, Long BJ, Sallis JF, Wooten WJ, Pratt M, Patrick K. 1996. A controlled trial ofphysician counseling to promote the adoption of physical activity. Prev Med 25:225-33.4. Eaton CB, Menard LM. 1998. A systematic review of physical activity promotion inprimary care office settings. Br J Sports Med 32:11-16.5. Frey I, Berg A. 2002. Erfassung der körperlichen aktivität in klinik und praxis. In: SamitzGMG, editor. Körperliche aktivität in prävention und therapie. München: Hans MarseilleVerlag GmhH. p. 81-86.6. Frey I, Berg A, Grathwohl D, Keul J. 1999. Freiburger fragebogen zur körperlichenaktivität—entwicklung, prüfung und anwendung. Soz—Präventivmed 44:55-64.7. Hardman AE. 2001. Issue of fractionization of exercise (short vs long bouts). Med SciSports Exerc 33:S421-S427.8. Kesaniemi YK, Danforth E, Jr., Jensen MD, Kopelman PG, Lefebvre P, Reeder BA.2001. Dose-response issues concerning physical activity and health: an evidence-basedsymposium. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33(6 Suppl.):S351-S358.9. Lee IM, Hsieh CC, Paffenbarger RS, Jr. 1995. Exercise intensity and longevity in men.The Harvard Alumni Health Study. JAMA 273:1179-84.10. Leon AS, Casal D, Jacobs D. 1996. Effects of 2,000 kcal per week of walking and stairclimbing on physical fitness and risk factors for coronary heart disease. J Cardiopulmonary Rehabil 16:183-92.11. Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ. 2001. The transtheoretical model of behavior change: a metaanalysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Ann Behav Med 23:229-46.12. Murphy MH, Hardmann AE. 1998. Training effects of short and long bouts of briskwalking in sedentary women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30:152-57.13. Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. 1986. Physical activity, all-causemortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med 314:605-13.14. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Buchner D, EttingerW, Heath GW, King AC, Kriska A, Leon AS, Marcus BH, Morris J, Paffenbarger RS,Patrick K, Pollock ML, Rippe JM, Sallis J, Wilmore JH. 1995. Physical activity andpublic health. JAMA 273:402-7.15. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. 1997. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change.Am J Health Promot 12:38-48.16. Steptoe A, Doherty S, Rink E, Kerry S, Kendrick T, Hilton S. 1999. Behavioural counselling in general practice for the promotion of healthy behaviour among adults at increasedrisk of coronary heart disease: randomised trial. BMJ 319:943-47.

6 / Frey and Berg17. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 1996.Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Author.

3. Assessment of physical activity by questionnaire can support counseling in many respects. Regular physical activity is regarded as an important component of a healthy lifestyle. New scientific evidence links regular physical activity to a wide array of physical and mental health benefits (8). Despite this evidence, most adults remain essentially