Transcription

The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1, 2008ConservationThe Getty Conservation Institute

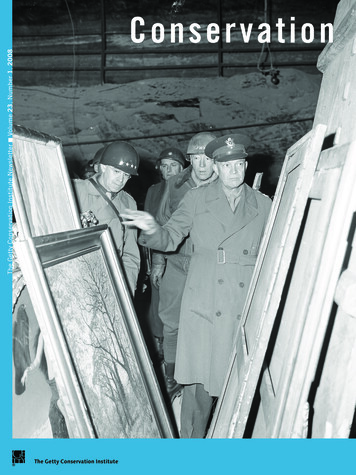

The GettyConservationInstituteNewsletterThe J. Paul Getty TrustJames Wood President and Chief Executive OfficerThe Getty Conservation InstituteTimothy P. Whalen DirectorJeanne Marie TeutonicoVolume 23, Number 1, 2008Associate Director, ProgramsKathleen Gaines Assistant Director, AdministrationJemima RellieAssistant Director, Communications and Information ResourcesGiacomo Chiari Chief ScientistSusan MacdonaldHead of Field ProjectsConservation, The Getty Conservation Institute NewsletterJeffrey LevinAngela EscobarEditorAssistant EditorJoe Molloy Graphic DesignerColor West Lithography Inc.LithographyThe Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advanceconservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to includeobjects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves theconservation community through scientific research, education and training,model field projects, and the dissemination of the results of both its own workand the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the GCI focuses on thecreation and delivery of knowledge that will benefit the professionals andorganizations responsible for the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage.The GCI is a program of the J. Paul Getty Trust, an international culturaland philanthropic institution that focuses on the visual arts in all theirdimensions, recognizing their capacity to inspire and strengthen humanisticvalues. The Getty serves both the general public and a wide range ofprofessional communities in Los Angeles and throughout the world.Through the work of the four Getty programs—the Museum, ResearchInstitute, Conservation Institute, and Foundation—the Getty aims to furtherknowledge and nurture critical seeing through the growth and presentationof its collections and by advancing the understanding and preservationof the world’s artistic heritage. The Getty pursues this mission with the conviction that cultural awareness, creativity, and aesthetic enjoyment are essentialto a vital and civil society.Conservation, The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, is distributedfree of charge three times per year, to professionals in conservation andrelated fields and to members of the public concerned about conservation.Back issues of the newsletter, as well as additional information regardingthe activities of the GCI, can be found in the Conservation section of theGetty’s Web site. www.getty.eduFront cover: General Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1945 inspecting artlooted by the Germans and stored in the Merkers salt mine duringWorld War II (behind him are General Omar N. Bradley, left, andLieutenant General George S. Patton Jr., right ). During the war,the United States created the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives(MFAA) teams—composed of cultural heritage experts—in orderto protect and salvage cultural sites in the war zone. Toward theend of the war, MFAA teams were given the monumental task ofcataloguing and returning the thousands of looted objects to theircountries of origin. Photo: Courtesy of U.S. National Archives.The Getty Conservation Institute1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700Los Angeles, CA 90049-1684 USATel 310 440 7325Fax 310 440 7702 2008 J. Paul Getty Trust

ContentsFeature4Dialogue10News in16Conservation20GCI News24Cultural Property at War Protecting Heritage during Armed ConflictBy Corine Wegener and Marjan OtterLooking to the past, we can learn much from the ways in which cultural heritage professionals have helped save cultural property at risk in war zones. Looking ahead, cultural heritageorganizations and professionals should combine their efforts under the banner of theInternational Committee of the Blue Shield and its affiliated organizations—the mosteffective mechanism for the protection of cultural property during armed conflict.Putting Heritage on the Map A Discussion about Disaster Managementand Cultural HeritageRohit Jigyasu, a conservation architect and risk management consultant based in India;Jane Long, vice president for emergency programs at Heritage Preservation in WashingtonDC; and Ben Wisner, a researcher associated with Oberlin College, the London School ofEconomics, and University College London, talk with Jeffrey Levin, editor of Conservation,The GCI Newsletter.Rethinking Crescent City Culture New Orleans Two and a Half Years LaterBy Kristin Kelly and Joan WeinsteinIn New Orleans, a number of cultural institutions were severely damaged by the floodingand high winds of Hurricane Katrina. After the hurricane, all cultural institutions, physically damaged or not, were faced with a New Orleans that had a different demographic andfar less tourism than the pre-Katrina city. The survival of the city’s cultural and historicinstitutions will depend upon their ability to adapt.“Where’s the Fire?” Teamwork for Integrated Emergency ManagementBy Foekje BoersmaThe gci has long worked to develop practical solutions to the technical problems faced inprotecting collections and buildings in emergency situations. Since 2004 the Institute hascollaborated with icom and iccrom on an education initiative focused on safeguarding museums from the effects of natural and human-caused emergencies.Projects, Events, and PublicationsUpdates on Getty Conservation Institute projects, events, publications, and staV.su rvey of conse rvation r eade r ssee page 30

FeatureaCultural Property at WarProtecting Heritageduring Armed ConflictBy Corine Wegener and Marjan OtterAt the end of 1943, as war raged in Europe, General Dwight D.sionals have helped save cultural property at risk in war zones.Eisenhower wrote to his commanders in Italy, clearly expressing hisLooking to the future, cultural heritage organizations and profes-intent to spare cultural property from damage whenever possible:sionals should combine their efforts under the banner of theToday we are fighting in a country which has contributed agreat deal to our cultural inheritance, a country rich inmonuments which by their creation helped and now in theirold age illustrate the growth of the civilization which is ours.We are bound to respect those monuments so far as war allows.This statement and other protective measures for culturalInternational Committee of the Blue Shield and its affiliatedorganizations—inspired by the 1954 Hague Convention—as themost effective mechanism for the protection of cultural propertyduring armed conflict.Lessons Learned from WWIIObservers of history know that cultural property usually suffersproperty were a direct result of concerted efforts by governments,during armed conflict. “To the victor go the spoils” was the attitudethe military, and cultural heritage professionals of many of theup until the end of the Napoleonic Wars. By World War II, thereAllied nations to protect Europe’s cultural heritage during Worldwere internationally accepted norms prohibiting the looting ofWar II. Nonetheless, countless icons of our shared cultural heritagecultural property during war. However, under Hitler, the Naziswere damaged, looted, or destroyed during the conflict. In response,devised the most organized art looting operation ever, stealingthe nations of the world gathered in the Netherlands to draft thecultural treasures from museums, churches, and private individuals1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property inin every country they occupied. While both sides in this war werethe Event of Armed Conflict, in an attempt to ensure that suchresponsible for the destruction of countless historic buildings,losses of cultural heritage during war would never again occur.monuments, and cultural heritage sites during military operations,However, recent conflicts in Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq1many Allied nations also mounted some of the most comprehensivedemonstrate that cultural heritage remains vulnerable during armedefforts ever attempted for the protection of cultural heritageconflict. In recent years, in Sarajevo the national library was burned,during war.and the facade of the National Museum of Bosnia and HerzegovinaIn the mid-1930s, many European museums and culturalwas pockmarked by snipers; in Afghanistan, objects in the Kabulinstitutions began long-range planning for war by making listsMuseum were defaced, destroyed, or looted and sold abroad, andof important objects, coordinating transportation via truck or rail,the great Buddhas at Bamiyan were obliterated; and in April 2003,and scouting appropriate offsite storage locations. Museumsthe Iraq National Museum was looted, and the ongoing lack of secu-stockpiled construction materials for crates and for reinforcing theirrity elsewhere in the country allows the continued looting andbuildings against bombing.destruction of thousands of archaeological sites.There is much we can learn from those instances in the pastin which some collecting institutions—through careful planning—successfully protected all or most of their collections during armedconflict. We can also learn from the ways in which cultural profes4Conservation, The GCI Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1 2008 FeatureWhen war finally arrived, many museum staff evacuated theirinstitutions, sending their most precious objects away for safekeep1. During World War II, the Hague Conventions on the Laws and Customs of Waron Land, 1899 (Hague II) and 1907 (Hague IV) governed the conduct of the war.Seizure of cultural property was clearly forbidden.

Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives(MFAA) Officer James Rorimer (rearcenter) supervises U.S. soldierscarrying paintings from Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany. MFAA teamswere part of an effective militaryeffort to protect and recover culturalproperty during wartime. (Prior tothe war, Rorimer was a curator at theMetropolitan Museum of Art in NewYork; he went on to become itsdirector.) Photo: Courtesy of U.S.National Archives.A museum guard standing amongempty frames at the Louvre Museum,Paris. During World War II, manymuseums throughout Europe removedtheir collections for safekeeping.Photo: Courtesy of U.S. NationalArchives.ing. At the Louvre in Paris, the galleries were emptied. In Amster-alongside those from the United States. Toward the end of the war,dam, Rembrandt’s famous Night Watch was rolled up and hidden.when Allied forces discovered repositories of thousands of objectsIn Italy, Michelangelo’s David was bricked up in its own tower, andlooted by the Nazis, the mfaa teams were given a new and monu-workmen built a protective structure in situ around the Arch ofmental task: removal of these objects to various collecting points forConstantine. Da Vinci’s The Last Supper fresco received a woodencataloguing and restitution to their countries of origin. The mfaawall reinforced with sandbags, saving it from a stray bomb that laterteams (recently recognized by the U.S. Congress for saving thou-destroyed much of the church. While museums in the United Statessands of works of cultural heritage) were part of the most effectiveremained open, many institutions, including the Metropolitaneffort ever undertaken by the military to protect cultural propertyMuseum of Art and the National Gallery, moved their mostduring wartime.important objects to remote sites.From the beginning of the war, cultural heritage professionalsThese extraordinary examples of how, in the past, culturalheritage professionals prepared for war and lobbied their govern-and organizations in several Allied countries lobbied for compre-ments to protect cultural property during war can serve as guides forhensive programs to protect cultural property, both at home andtoday’s professionals on ways to protect collections during and afterabroad. One such U.S. committee helped create the Monuments,conflict in the future.Fine Arts, and Archives (mfaa) teams within the U.S. Army CivilAffairs Division. The mfaa teams—mostly composed of museumCultural Property in a Twenty-First-Century Warprofessionals, art historians, and other cultural heritage expertsWhile World War II provides multiple instances of museumsalready serving in the military in another capacity—were respon-preparing for major armed conflict, more recent examples of actionssible for identifying important cultural sites on military maps so thatby other courageous colleagues in areas of conflict are also instruc-pilots and artillery could avoid them. mfaa officers followed thetive. The looting of the Iraq National Museum is a case in point.battle, entering liberated towns just behind the combat forces inThe press initially reported that more than one hundred seventyorder to protect and salvage cultural sites. Several Allied nationsthousand objects, the entire contents of the museum, had beenalso organized a small number of mfaa-type troops who workedlooted; it was later learned that there were actually closer to halfConservation, The GCI Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1 2008 Feature5

The main lobby of the Iraq NationalMuseum, May 2007. As a precautionagainst anticipated looting, the frontdoors (at left) were sealed withcement blocks prior to the U.S.invasion in April 2003. Unfortunately,looters were able to enter parts of themuseum through other ways. However,key staff members hid most of themuseum’s collection—a measurethat was instrumental in saving asignificant portion of the collection.Photo: Corine Wegener.a million objects in the collection, many of which had not beenThe Coalition Forces in Iraq did not have the kind of mfaacatalogued or were deposited there from other regional museumsunits that were present during World War II. While most countriesfor protection. In fact, only about fifteen thousand objects werestill have Civil Affairs units, few cultural heritage personnel serve intaken. Key staff members removed and hid most of the collectiontoday’s military, leaving most military commanders without thisin the weeks prior to the U.S. invasion. While the losses were tragic,expert advice. Furthermore, units receive little training on culturalthey were a fraction of what they might have been had the staff notproperty protection beyond instructions to avoid damage duringcarefully planned and executed an evacuation of the galleries.military operations. Some European nations maintain Civil-In addition, staff used cement blocks to close up several entrancesMilitary Cooperation units, including a small force of reservistsand storage areas to hinder looters, surrounded dozens of immov-who are cultural heritage professionals; however, their deploymentable sculptures and friezes with foam to protect against bombis often hindered by their nation’s rules regarding entry into combatdamage, and sandbagged the floor of the Assyrian Gallery to protectareas. One result of these limitations was that in the spring andthe large stone friezes in case they fell during bombing. Finally, wellin advance of the invasion, the staff painted the international symbolfor the protection of cultural property, the blue shield, on the roofof the museum.While these precautions were instrumental in saving muchof the collection, small oversights proved disastrous. For example,the lack of a key control system allowed keys for secure storage tofall into the hands of the looters, giving them access to areas theymight not otherwise have reached. More than four thousand ancientcylinder seals were lost from one storage area alone. Comprehensiveemergency planning on the part of museum staff can prevent suchoversights.Smashed Roman sculptures from theancient site of al Hatra at the IraqNational Museum, May 2003. Here foampadding did not protect these sculptures,which were purposely destroyed bylooters. Photo: Corine Wegener.6Conservation, The GCI Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1 2008 FeatureDamaged lion sculpture from Tel Harmalat the Iraq National Museum, May 2003.Looters, unable to remove the sculpture,smashed its head. A matching sculpture,covered in foam padding, was left intact.Photo: Corine Wegener.

summer of 2003, the team of cultural heritage professionalsworking with the staff of the Iraq National Museum was very small,including a few government civilians and military personnel (noneof whom were conservators) from the United States, the UnitedKingdom, Italy, and the Netherlands.After the looting, Iraq National Museum staff had to deal withdamaged objects left behind. What looters could not carry away,they often smashed, either out of malice or to obtain salable fragments. The museum conservation staff had little or no advancedconservation knowledge (United Nations sanctions had longprevented staff from receiving training), and broken objects lan-The Blue Shield symbol near a staffentrance at the KunsthistorischesMuseum in Vienna. Photo: CorineWegener.guished in the conservation lab. Many cultural heritage professionals—including conservators, archaeologists, and curators—volunteered to assist but were denied entry because they were not part oftheir country’s ministry of state team or part of a nongovernmentalaid organization, which could enter the country with ease and set upoperations. The few cultural professionals who entered Iraq did sousing temporary press passes, or they were brought in by theirThe Second Protocol of the Hague Convention, drafted ingovernments to make assessments—not to perform conservation.1999, gave the icbs a specific function under the Convention. Among(It would be nearly a year before the Italian government sentother things, it asks parties to the Convention to consider registeringconservators to provide training for the Iraqi museum staff.)a limited number of refuges, monumental centers, and otherTo avoid these problems in the future, cultural heritageimmovable cultural property in the International List of Culturalprofessionals need to work collaboratively. The obvious and bestProperty under Enhanced Protection (maintained by unesco); toway to do this is to work within a nongovernmental organizationconsider marking certain important buildings and monuments withmodeled on humanitarian aid organizations like Doctors Withouta special protective emblem of the Convention (the blue shield); toBorders or the International Committee of the Red Cross—in otherestablish a system of protection for cultural heritage of the greatestwords, the International Committee of the Blue Shield (icbs) and itsimportance for humanity; and to establish special units within theconstituent organizations.military responsible for protecting cultural property. The SecondThe Blue Shield CommitteesProtocol names icbs as a nongovernmental organization with therelevant expertise to recommend specific cultural property forThe icbs was inspired by the 1954 Hague Convention, which wasinclusion on the International List. icbs and its constituent bodiesthe first international treaty focused exclusively on the protection ofare also named as eminent professional organizations with formalcultural heritage in the event of armed conflict. States Parties to therelations with unesco that can advise and assist the Committee ofHague Convention are a network of more than one hundred nationsStates Parties to the Hague Convention.that have agreed to mitigate the consequences of armed conflict andto take preventive measures during peacetime, rather than duringhostilities, when it is usually too late. (While neither the UnitedStates nor the United Kingdom has ratified the Convention, in 2004the United Kingdom stated its intention to do so, and there is amovement under way to promote U.S. Senate ratification.)The icbs was founded in 1996 to work for the protectionBlue Shield National CommitteesA country need not be a States Partyto the Hague Convention in order toestablish a Blue Shield national com-of cultural heritage by coordinating preparations to meet andmittee. Established national commit-respond to emergency situations; however, the icbs essentiallytees include those in Australia, Belgium,consists of only the directors of its constituent bodies: the Coordinating Council of Audio Visual Archives Associations, the International Council on Archives, the International Council of Museums,the International Council on Monuments and Sites, and theBenin, Chile, Cuba, Czech Republic,France, Israel, Italy, Macedonia,Madagascar, the Netherlands, Norway,Poland, Senegal, United Kingdom andIreland, and the United States.International Federation of Libraries and Archives.Conservation, The GCI Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1 2008 Feature7

The 353rd Civil Affairs Command, an Army reserveunit from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, receivingcultural property training from the U.S. Committeeof the Blue Shield (USCBS). For this training, theUSCBS partnered with the AIC and the ArchaeologicalInstitute of America to provide an overview of culturalproperty protection to this unit, which, like all CivilAffairs personnel, is responsible for cultural propertyissues in military theaters of operations. Photo:Corine Wegener.Working group meeting of the Association of National Committees of the BlueShield (ANCBS) in the Netherlands, March 2007. ANCBS will serve as thecentral contact for aid requests and for administrative coordination of reliefoperations among other organizations. Photo: Leif Pareli.A number of countries have established national committeesfully, and because the usefulness of the project was unquestioned.of the Blue Shield, which can play a crucial role in the execution ofIt was also important that the request for help came from theactions required by the Hague Convention. Currently there areNational Committee of the Blue Shield of the Czech Republic itself.seventeen established Blue Shield national committees and twentyThis Blue Shield project was executed within the regular culturalcommittees under formation (see sidebar). Organizations represent-channels and therefore was quite effective. It was relatively easy toing museums, libraries, archives, and archaeological sites make uprealize and could be replicated in other natural disasters.the membership of these national committees. National Blue ShieldThe U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield (uscbs) was foundedcommittees may focus on domestic or international needs andin 2006 in response to the looting and subsequent problems innatural disasters, armed conflict, or both. Blue Shield committeesproviding international assistance to the Iraq National Museum.can also help raise awareness about cultural property at risk fromuscbs, a charitable nonprofit organization (as are all nationalarmed conflict and sometimes act in an advisory capacity to traincommittees), focuses on the following: offering cultural propertycultural professionals or provide them with necessary expertise.protection training to U.S. military units deploying to Iraq, Afghan-Two national committees—one in the Netherlands and one in theistan, and other parts of the world; promoting U.S. ratification ofUnited States—illustrate activities that committees might under-the 1954 Hague Convention; and coordinating with domestictake to promote protection of cultural property.cultural heritage organizations and other national Blue ShieldDuring flooding in the Czech Republic in August 2002, thecommittees to provide a worldwide deployable force of culturalDutch Ministries of Culture and Foreign Affairs financially aidedheritage professionals to advise and assist in the protection ofBlue Shield Nederland (founded in 2000) to buy equipment tocultural property damaged or threatened by armed conflict.preserve paper objects in several Czech museums. Blue ShieldThe military training program is the most active, providingNederland also organized the transport of the equipment and theinstruction for Civil Affairs units. uscbs, the Archaeologicalassistance of senior officers of the Dutch National Archive, whoInstitute of America, and the American Institute for Conservationoffered their expertise to begin the monumental task of paperof Historic and Artistic Works (aic) each provide cultural heritageconservation. The initiative began slowly, due to coordination andexperts in their respective fields to present a daylong course on thelogistical problems; however, two thousand cubic meters of paperidentification and protection of cultural property in all media.were frozen to preserve these materials in advance of treatment.This in turn gives Civil Affairs soldiers the basic knowledge to(The experience acquired during this project enabled Blue Shieldadvise the commanders of the combat units they support on how toNederland to provide similar assistance after the 2004 fire thatdeal with cultural property protection issues. The training, fundeddestroyed the Anna Amalia Library in Germany.)by the organizations offering the training, is provided at no costBlue Shield Nederland could act in this instance because therewas no immediate threat to life, because the authorities cooperated8Conservation, The GCI Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1 2008 Featureto the military. The response has been very positive, and a numberof future sessions are scheduled.

Association of National CommitteesSince icbs consists only of the directors of its constituent bodies,it lacks the ability to deploy personnel to assist in a cultural heritageemergency. For this reason, the icbs and various Blue Shieldnational committees initiated the development of an Association ofNational Committees of the Blue Shield (ancbs) in September 2006.ancbs will serve as the central contact for requests for help topreserve endangered cultural heritage and provide administrativecoordination of relief operations among other organizations. ancbswill promote the Blue Shield organization, both in the heritagesector and among other relief organizations. Finally, it will maintainan international list of available specialists in the area of disasterprevention and containment in each member country, along witha central information and expertise center and Web site.The city of The Hague has offered financial and logisticalsupport for ancbs to house its headquarters in that city. In the pastyear, the ancbs working group has drafted organizational statutes,has begun developing a Web site, and has continued to assess its rolealongside that of the ancbs. In 2008 ancbs plans to incorporate inthe Netherlands and begin fund-raising to finance future operationswith three goals in mind. First, it wants to provide expertise tocultural heritage organizations seeking advice on preventivemeasures, preservation, and restoration of cultural heritage throughthe self-help database on the Blue Shield Web site (in cooperationwith expert organizations in this field). Second, it plans to developteams of cultural heritage experts who will provide direct assistanceto cultural heritage organizations affected by natural disasters orarmed conflict, and it plans to provide the logistical means to deploythese experts where they are most needed (in a manner similar tothat of organizations like Doctors Without Borders). And third,Blue Shield national committees will stimulate preventive measuresby raising awareness and improving coordination with their respective governments and military organizations.The success of these plans depends greatly on the level ofparticipation and commitment of cultural heritage communities ineach nation to their national Blue Shield committees—and on thedevelopment of national committees where they do not exist. As isthe case with institutional emergency plans, this type of coordination cannot be done on an ad hoc basis in the midst of a disaster, norcan it be done amid turf battles among the various interested parties.It must be a long-term, coordinated, mutually beneficial processinvolving cultural heritage organizations from all sectors.In the past, one of the most important measures to protectcultural property during armed conflict was the preventive planningextending their worst-case scenario to the possibility of war.Emergency planning is even more important today, given thewillful destruction and looting witnessed during recent conflictsand the possibility in many places of terrorist attacks. Culturalheritage organizations should recognize that government andmilitary resources often do not have the expertise or availablepersonnel to provide assistance, particularly if they are concernedwith saving lives. Therefore, cultural heritage organizations mustthemselves assume responsibility for protecting collections andplanning for the worst.Cultural heritage professionals also have a responsibility tocolleagues around the world to work together to protect heritageduring armed conflict. The International Committee of the BlueShield is the most logical umbrella organization under which thiseffort can be carried out. Blue Shield national committees, byuniting the many cultural heritage organizations and individualprofessionals within a nation, can better influence lawmakers,increase public awareness, and improve coordination with theirrespective militaries—which, as the situation in Iraq demonstrates,is crucial for protecting and preserving cultural heritage in warzones. The various national committees of the Blue Shield are alsostronger when they band together as the Association of NationalCommittees of the Blue Shield, providing a central clearinghousefor requests and supporting an international network of culturalheritage professionals eager to help by putting their skills to use.The choice is ours. If we, as cultural heritage professionals,continue to act as individuals and function within a variety ofdiscrete organizations, we will almost certainly fail the next timecolleagues in a war-torn country need us. However, if we unite insupport of the Blue Shield organizations created to protect culturalheritage during armed conflict, we can make our voices heard andperhaps even be influential enough to prevent the “next time.”Corine Wegener is an associate curator in the department of Architecture, Design,Decorative A

The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter Volume 23, Number 1, 2008 The J. Paul Getty Trust James Wood President and Chief Executive Officer The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico Associate Director, Programs Kathleen Gaines Assistant Director, Administration Jemima Rellie Assistant Director, Communications and Information Resources