Transcription

Paving ParadiseDATABASE CONTENT REMOVALAND INFORMATION PROFESSIONALSTextby AMY AFFELTJAN FEB 2010VOL. 34 NO 1This article originally appeared inONLINE, Exploring Technology & Resources forInformation ProfessionalsVolume 34, NO 1, Jan/Feb 2010, Pages 14–17Copyright 2010by Information Today, Inc.This article is reprinted in its entirety from the January/February 2010 issue of ONLINE magazine, published by Information Today, Inc.Used with permission. All rights reserved. Individuals may download, store, and print a single copy. All commercial uses, includingmaking printed copies for distribution in bulk at trade shows or in marketing campaigns and all commercial reprints require additionalpermission from the publisher. www. infotoday.com

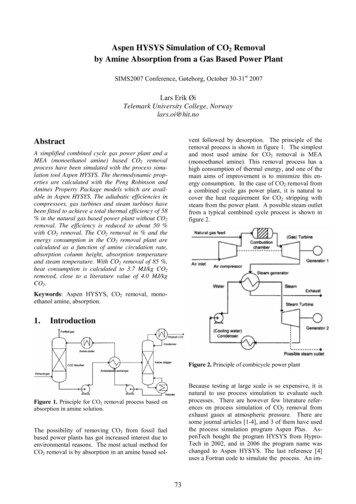

2010JAN FEB 2010Volume 34 – Number 1ISSN: 0146-5422E x p l o r i n g Te c h n o l o g y & R e s o u r c e s f o r I n f o r m a t i o n P r o f e s s i o n a l sContentscolumnsLand48 InfoLitFoundations of Information Literacy:Learning From Paul ZurkowskiWilliam Badkefeatures51The Dollar SignFinance, Personally SpeakingMarydee Ojala1454Paving Paradise: DatabaseContent Removal andInformation Professionals5818Creative Commons: CopyrightTools for the 21st CenturyCrawford at LargeOne, Two, Some, Many: Search Resultsand MeaningWalt Crawford61By Laura Gordon-Murnane22Mobile Websites With Minimum EffortJeff WisniewskiBy Amy Affelt18Control-ShiftResources to EncourageEntrepreneurial Creativityand InnovationHardcopyYou Don’t Look Like a Librarian:Shattering Stereotypes and Creating PositiveNew Images in the Internet AgeLibrary Mashups: Exploring New Ways toDeliver Library DataComplete Web MonitoringBy Stephen FadelThe Kovacs Guide to Electronic LibraryCollection Development: Essential CoreSubject Collections, Selection Criteria, andGuidelines, second editionDeborah Lynne Wiley3264Online SpotlightThe Virtues of Finding and ForgettingMary Ellen Bates32Comparing Search Enginesfor Quick and Dirty AnswersBy Cybèle Elaine Werts36What Customers Want FromKindle Booksdepartments5 HomePageGhost Authors, Teachable MomentsMarydee OjalaBy Nancy A. Allmang and Stacy M. Bruss40Get a Life: ComparingOnline Biography ResourcesBy Joann M. Wleklinski45What Are Libraries Doingon Twitter?By David StuartCover design by Norma J. Neimeister813Industry NewsCompiled by Suzanne SabroskiSearch Engine UpdateNew Search Features, Developments,and ContentGreg R. Notess63Index to AdvertisersVisit ONLINE at www.onlinemag.net

Paving Paradise: Database Content Removal and Information ProfessionalsText by AMY AFFELTI didn’t expect to be channeling JoniMitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi” as I readThe New York Times one morning inearly September. But an article mentioning a court order for Westlaw and LexisNexis to remove judicial decisions had mehumming, “You don’t know what you’vegot till it’s gone.”The article discussed a lawsuit thatbegan in 2004 (Klein v. National RailroadPassenger Corp., 2:04-CV-00955, U.S.District Court, Eastern District ofPennsylvania). It involved two teenageplaintiffs who trespassed onto a parkedAmtrak rail car and were severely burnedwhen they got too close to a 12,000-voltcatenary wire. The plaintiffs wereawarded a jury verdict of 24 million.While Amtrak’s appeal was pending, itagreed to pay an undisclosed sum to theplaintiffs. As part of that settlement, theparties asked Judge Lawrence F. Stengelto “direct LexisNexis and Westlaw toremove the decisions and orders listedfrom their respective legal research services/databases.” Judge Stengel agreed todo so; LexisNexis and Westlaw complied.The legal arguments used by the attorneys to accomplish this feat remain amystery because all of the court papersare under seal. What is known, however,is that in the 5 years of litigation, severalsignificant legal opinions, including onediscussing the burdens of proof requiredto demonstrate awareness of potentialaccidents based on previous incidents,were handed down. Those opinions wereall withdrawn. In a legal system based onprecedent, the ramifications of thisaction are very troubling.TAKING THE TREESCitizens might be upset about thisdevelopment not only because of anarguable First Amendment breach butalso because Amtrak enjoys federal funding. Information professionals (IPs) haveadditional causes for concern. Previously,as an IP, the only major missing content Iwas aware of were articles removed as aresult of the Tasini decision, a 2001Supreme Court case involving freelancewriters who felt unfairly compensated bypublishers who reprinted their articles inelectronic databases without theirpermission. These articles seemed to befew in number and did not seem to contain information that could make orbreak a case.This may change. On Oct. 7, 2009, theU.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in an appeal from the SecondCircuit regarding the class action settlement of publishers’ payments to thousands of freelancers involving bothcopyrighted and unregistered works. Theformal question in Reed Elsevier, Inc., etal. v. Irvin Muchnick, et al. is, “Does 17U.S.C. §411(a) of the Copyright Actrestrict the jurisdiction of the federalcourts over copyright infringementactions?” (Updates to Literary Works inElectronic Databases Copyright Litigation509 F.3d 136 [2d Circ. 2007] are available atwww.copyrightclassaction.com.)PUTTING THEM IN A TREE MUSEUMIn Klein v. National Railroad, however,the first obvious problem lies in the factthat the decisions—and, thus, the legalprecedent and valuable documentedresearch that could be used by attorneysinvolved in subsequent lawsuits of a similar nature—are lost. If the playing fieldwas level and no one ever had access tothese decisions, the situation would beless problematic. However, these decisions were available on both theLexisNexis and Westlaw databases at onetime. Thus, many people possess PDFs ofthese opinions. But those conductingresearch after Aug. 6, 2009, are unable toobtain the PDFs through the legal onlineresearch services. They cannot fairlycompete with other law or consultingfirms who researched the issue earlier.When questioned about its decision tocomply with the court order, LexisNexisreferred me to an outside public relationsfirm. I spoke with three LexisNexisemployees, who offered this statement:“All LexisNexis can say at this time aboutthe issue is that we received a letterfrom the U.S. District Court for theEastern District of Pennsylvania containing an Order vacating certain Decisionsand Orders issued by that Court. The letter requested and directed that thosedocuments be removed from thelexis.com service. We have compliedwith the Court’s request and direction.Because we cannot say more than thatright now, there is unfortunately no othercontact to send you to who could providemore information.”JAN FEB 2010

Paving Paradise: Database Content Removal and Information ProfessionalsA search in genfed;mega on LexisNexisresulted in the judge’s order to remove,along with a listing of the removed documents. However, I was unable to get adefinitive answer from LexisNexis regarding whether or not it is the company’sstandard practice to make a notation forresearchers to indicate when documentsare removed. When doing future legalopinion searches, I am not certainwhether there would be a way to tell if asearch was missing a document that hadbeen removed.Westlaw’s policy is more reassuring.Westlaw stated that “in the infrequent eventthat we are ordered by the court to [remove]a decision [from] Westlaw, we will complywith the order, deleting the text of the decision but keeping the title of the case and itsdocket number. We also publish the court’sorder to remove so there’s a clear record ofthe action.” When asked if content wouldever be removed due to a situation otherthan a court order, John Shaughnessy, senior director of communications forThomson Reuters, stated that court orderssealing a decision or draft decisions thatwere never formally signed or filed mightalso be removed. Shaughnessy stated thatin all opinion removal situations, Westlaw’spreferred practice is to remove only the text,leaving the header information for futurereference.SCREEN DOOR SLAMMINGBecause the actions in Klein v. NationalRailroad received so much press, manybloggers, law librarians, attorneys, FirstAmendment activists, and others immediately uploaded PDFs of the decisions totheir websites. The first two results of aGoogle search I conducted on Sept. 2,2009, for “Klein v Amtrak” yielded the following sites that had links to the documents: www.volokh.com and http://lawprofessors.typepad.com. Furthermore,apparently the attorneys did not considerthe fact that the decisions may have beenprinted in the hard-copy federal supplement and would be available at any lawlibrary.IPs know, however, that most researchprojects we work on do not involve issuesthat are so widely reported. Any missingcontent, not just legal opinions, couldcause our research abilities and credibility to be questioned. How will we know ifthe vital piece of information that weneed has been removed from a database?What prompts databases to remove content, and how is that removed contentdocumented? For IPs who work in litigation, opposing counsel with documentsthat we thought did not exist, or werenever available, is a disastrous situationthat holds us directly accountable.ANALYST REPORTSThe first pieces of content that I investigated were analyst reports from the investment banks and market research reportsfrom firms such as International Data Corp.(IDC) and Datamonitor. Thomson Reuters isthe gold standard for these reports, and JohnWebber, director of research, stated that“very rarely” are reports removed fromThomson Research. Thomson Reuters viewsitself as the publisher of these reports; theactual content of the reports is consideredthe intellectual property of the firms thatwrite them. Each contributing firm has anindividual contract with Thomson Reuters,and Webber emphasized that ThomsonReuters views its obligations to its contributors and to its clients with equal weight.If an IP searched for a report that hadbeen removed, the report would not belisted in the results set. However, Webberstated that if the IP called ThomsonReuters customer support, the internalsystem would be able to find out if something had been removed. This is goodnews for the IP. Although it involves a little tenacity in actually calling aboutsomething that one believes should bethere but is not, there is a way to find outif something had been on ThomsonReuters at one time but was removed.YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU’VE GOTDow Jones Factiva is in a unique situation—it not only aggregates third-partydata but is also part of a company that isa creator of content (The Wall StreetJournal, Dow Jones Newswire, Barron’s).The editorial practices and deletions policies of Dow Jones original content arecompletely separate from the Factivadatabase product policies. The latter hasa formal legal deletions policy that is contained in its quality charter.According to Ines Magarinos, managerof content quality for Dow Jones Factiva,third-party content is only removed “incases where it would be either a breach ofcontract or unlawful for it to remain.” Forcontent that is predominantly licensed,each license agreement has a clauseregarding removal. Factiva is obligated bythese agreements to remove content at theend of the license term or if the contentprovider notifies Factiva that it has a legitimate concern regarding the accuracy orlegality of the content. Additionally, circumstances causing Factiva to be in violation of the law by retaining content—inviolation of a court order to remove—would prompt Factiva to remove that content. Searchers would not be able to see ifa document was removed, but Magarinosstated that Factiva customer service wouldbe able to find that information and relayit to the user.Dialog and EBSCO have very similarcontent availability policies, and bothdescribe themselves as aggregators oflicensed content. As intermediariesbetween publishers and libraries andresearchers, they take their cues from thepublishers in determining treatment ofquestionable content. Both Scott Bernier,senior director of marketing at EBSCOPublishing, and Libby Trudell, VP, marketdevelopment at Dialog, LLC, emphasizedthe importance of upholding the licensing agreements with their providers.When asked for specific anecdotes, bothBernier and Trudell mentioned Tasini asgrounds for article removal. Both executives also mentioned particular circumstances that may be unique to theirindividual services. Bernier stated that atEBSCO, the most common issue affectingcontent availability is when a publisherdecides to terminate its relationship withan aggregator (this issue is very familiar tothose of us still longing to accessBloomberg and the Financial Times databases via LexisNexis). In the “extremelyrare” instances in which an article isremoved, it is impossible to determine onEBSCO’s database whether that article wasremoved. However, Bernier stated that ifthe circumstance is that EBSCO does nothave the right to include an article, it addsthe following statement to the article’scitation page: “This database normallyincludes full text of articles available fromthis publication. However, this particulararticle is not included at the request of therights holder.”JAN FEB 2010

Paving Paradise: Database Content Removal and Information ProfessionalsFor IPs who work in litigation, opposing counsel with documentsthat we thought did not exist, or were never available, is a disastroussituation that holds us directly accountable.Trudell mentioned the possibility of anarticle’s subject complaining that it isdefamatory. In that case, Dialog refers thematter to the publisher, requesting instruction regarding retention or removal. Trudellalso discussed the economic impact ofrarely used and outdated files. Low use andantiquated content could prompt Dialog totake a database offline.UNTIL IT’S GONEIf the online information industry werelooking for a company with best practices,ScienceDirect from Elsevier seems to fit thebill. Lindi Belfield, senior product managerfor ScienceDirect, discussed a specific casethat was the impetus that created Elsevier’svigorous review process for articles underconsideration for withdrawal, retraction, orremoval. Belfield explained that, in 2002, ascientific society demanded removal of anarticle from its Human Immunology journal, and Elsevier complied. Even at this initial removal stage, Elsevier posted a page inScienceDirect stating, “This article hasbeen removed by the Publisher.”However, members of the scientificcommunity asked Elsevier to reconsider.They felt that, as professional colleagues,they should bear the burden of decidingwhether content should be removed frompeer-reviewed journals. As a result, Elsevierreviewed its removal process and decidedin favor of the scientists. It put a process inplace (http:// libraryconnect.elsevier.com/lcn/0102/lc 010207.html) in which publishers fill out a form with a series of questions, ensuring that Elsevier’s policyregarding retraction is followed. The formrequires that the publishers clearlyexplain why the retraction is necessary.ScienceDirect then processes the form sothat it knows the specific actions takenregarding the retracted article, where it isstored, and the reasons that prompted theretraction. Belfield, along with the seniorvice president general counsel and seniorvice president of academic relations,checks the forms and the removal verbiageprovided by the publisher. The originalHTML of the article is then replaced withthe text of the form on ScienceDirect. ThePDF remains in ScienceDirect but with ared watermark on each page that says“RETRACTED.” Elsevier also holds the publisher responsible for adding a retractionnotice in a subsequent issue of the journal,using the same text as the retraction formand with a link to the retracted article.Regarding complete physical removal,Belfield stated that it is very rare andwould involve extreme situations such asan article that gives life-threatening information, such as an incorrect drug dosage,or an article involved in a serious legalmatter. IPs can take comfort in the factthat, in these cases, even though theHTML and PDF are removed, they arereplaced by HTML pages explaining thereasons for removal. Later, a notice is published and reciprocally linked.LEAVE ME THE BIRDS AND THE BEESInitially, I approached the researchrequired for this article with a forbiddingsense of gloom and doom. I was afraid thatcontent was being removed from databases at will, with no consideration of theresponsibility that IPs feel for the searchesand results that they conduct and provide.After completing the interviews and investigations, however, I am optimistic andhave a higher comfort level.Almost none of the database companies discussed in this article remove content cavalierly. They have policies in placeto ensure that researchers are able to findout about content that has beenremoved. They hold their providersaccountable through rigorous processesthat force those providers to make strongcases for removal of content. Almost all ofthe vendors discussed in this article arecommitted to upholding these standardsand keeping the removal request processquite rigorous. Similarly, we as IPs have aresponsibility to pursue situations inwhich we believe content has beenremoved. It is critical that we are tenacious in contacting vendors’ customerservice units to obtain answers to contentremoval questions.In the information industry’s currentclimate, content is king. The ability tofind quality content and add value to thatcontent is what distinguishes the information professional from the Googler. Itis refreshing to discover that in the area ofcontent integrity, providing IPs withaccess to high-quality information anddata remains a top priority of the database vendors. In an environment inwhich both IPs and vendors sometimesfind themselves struggling to survive, it ismy hope that we can use this shared dedication to superior quality content inorder to unite and work together in waysthat are mutually beneficial.Amy Affelt (aaffelt@compasslexecon.com) isdirector of database research at Compass Lexecon.Comments? Email letters to the editor tomarydee@xmission.com.JAN FEB 2010

50%OFFPersonal subscription offerfor ONLINE magazine50% savingsfrom current ratesU.S.: 129.95 65Canada/Mexico: 145 72.50Outside North America: 172 86Subscribe Now!Call 800-300-9868to order.143 Old Marlton Pike Medford, NJ 08055www.infotoday.com/ONLINE

the intellectual property of the firms that write them. Each contributing firm has an individual contract with Thomson Reuters, and Webber emphasized that Thomson Reuters views its obligations to its contribu-tors and to its clients with equal weight. If an IP searched for a report that had been removed, the report would not be listed in the .