Transcription

CAMPUSBARGAININGAT THECROSSROADSProceedingsTenth Annual ConferenceApril 1982JOEL M. DOUGLAS, EditorNational Center for the Study ofCollective Bargaining in Higher Educationand the ProfessionsBaruch College-CUNY

Copyright(§)1982 inu. s.A.by The National Center for the Study of Collective Bargainingin Higher Education and the Professions Baruch College, City university of New YorkAll rights reserved. No ,t;drt: oj'. this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, or transmitted in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,recording, or otherwise, without the priorpermission of the publisher.Price 15.00

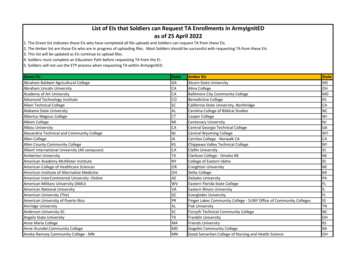

TABLE OF CONTENTS1.INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Joel M. Douglas12.CAMPUS BARGAINING AND THE LAW: A DECADE OF HIGHEREDUCATION COLLECTIVE BARGAINING--1972-1982. . . . .June M. Weisberger73.THE THEORY OF NEGOTIATION: GETTING TO YES . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Roger Fisher4.DISSECTING THE NEW RIGHT AND ITS THREAT ·ro COLLECTIVEBARGAINING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Roxanne Bradshaw25THE IMPACT OF UNIONS ON ACADEMIC STANDARDS ANDACCREDITATION IN HIGHER EDUCATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Thomas Shipka335.6.THE INDUSTRIAL MODEL OF ACADEMIC COLLECTIVE BARGAINING .Michael B. Lehmann7.THE USE AND ABUSE OF PART-TIMERS--!: CASUAL EMPLOYEES SCABS OR SAVIORS? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Nancy L. Hodes8.THE USE AND ABUSE OF PART-TIMERS--II . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Nuala McGann Drescher9.MANAGERIAL DISCRETION, FINANCIAL EXIGENCY AND REDUCTIONIN FORCE: THE EXPERIENCE IN NEW JERSEY'S PUBLIC, TWOYEAR COLLEGES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Ernest GrossTheodore SettleJames Begin184856657310.ACADEMIC FREEDOM IN CANADA IN THE 1980's . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .V. W. Sim8311.A DECADE OF CAMPUS BARGAINING: AN OVERVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . .Kenneth P. Mortimer9712.THE NATIONAL CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN HIGHER EDUCATION: THE FIRST TEN YEARS--PART I . 107Joel M. Bouglas13.THE NATIONAL CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN HIGHER EDUCATION: THE FIRST TEN YEARS--PART II . 113

CAMPUSBARGAININGAT THECROSSROADS

1. INTRODUCTIONThe Decennium Conference of the National Center for theStudy of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and theProfessions was a milestone for both Baruch College as well asthose engaged in academic collective bargaining.Ten yearsago, when the Center was' first established, there were thosewho expressed doubt as to the viability of an organizationdevoted to what was described as a 'unique phenomena .Today,nearly 200,000 professors live under collective rofessionalemployees in colleges and niversities are also unionized.Clearly, this 'unique phenomenon' has growni it is the rareinstitution that is not involved in some facet of academiclabor relations.The previous ten years have not been easy for the Center.Financial constraints, budgetary problems, the shifting legalenvironment, maintenance of a neutral base and other assortedproblems have had to be overcome.Much of the credit for oursuccess must be given to the three previous Directors, MauriceBenewi tz, Tom Mannix and Ted Lang.Aaron Levenstein, whoserved as Associate Director during the tenure of the past twoDirectors, must receive a special word of thanks.Two otherpeople must be singled out for making the Center what it istoday: Evan G. Mitchell, for having run ten annual conferencesand for treating each one with the same enthusiasm that shegave the firsti and Ruby N. Hill, who has been Secretary to thelast three Directors.Design of the ConferenceTaking stock of the events of the past decade was thefocal point of the Decennium Conference.The first plenarysession reviewed the major legal decisions of the past decade.The second session focused on the impact that the expansion ofcollective bargaining has had on university campuses, withparticular emphasis on campus governance.These two sessionsprovided a setting for an examination of current criticalissues that campus bargainers face.Among these were theattack on academic freedom, the use and abuse of part-timers,and the relationship between unionization and the quality ofacademic standards.Yeshiva was the theme of the Monday luncheon, however, inaccordance with the wishes of the speaker, the remarks were offthe record and therefore not a part of this proceeding.Thespeaker, a member of the National Labor Relations Board, was inthe delicate position of having ruled on a series of Yeshivacases that were due out the week after the conference.The ProgramSuggestions for topics and speakers were obtained from theFaculty and National Advisory Committees ofthe Center.Furthermore, there now exists an informal group known as"friends of the Center" who frequently submit suggestions forpapers and research proposals.To these three groups go thecreditforthecontinuedsuccessoftheprogram.1

Monday Morning, April 26, 19829:00INTRODUCTIONJoel M. Douglas, Director, NCSCBHEPWELCOMEJoel Segall, President, Baruch College, CUNY9:3011:0012: 4 5PLENARY SESSION ICAMPUS BARGAINING AND THE LAWSpeaker:June M. Weisberger, Professor of Law,University of Wisconsin Law SchoolModerator:Aaron Levenstein, Professor EmeritusBaruch College,CUNY,Former Assoc.Dir., NCSCBHEPPLENARY SESSION IIGETTING TO YES: THE THEORY OF NEGOTIATIONSpeaker:Roger Fisher, Professor of Law, HarvardLaw School, Dir., Harvard UniversityNegotiations Professional Staff Congress/AFTModerator:Frederick Lane,Professor of PublicAdministration, Baruch College, CUNYLUNCHEONTopic:THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONSITS IMPACT ON CAMPUS or Relations BoardPresiding:Joel M. Douglas, Director, NCSCBHEPNationalMonday Afternoon, April 26, 19822:30SMALL GROUP SESSIONSGroup A:DISSECTING THE NEW RIGHT AND ITS THREATTO COLLECTIVE BARGAINING2

Speaker:RoxanneBradshaw,Chairperson,Higher Education CouncilDiscussant:Dorrit Cowan, Assistant ProfessorSpeech Baruch College, CUNYModerator:JuliusManson,ProfessorBaruch College, CUNYGroup B:ACADEMIC STANDARDS AND ACCREDITATIONSpeaker:Thomas Shipka, Professor of PhilosophyPresident,YSUChapterofOEA,Youngstown State usiness, Columbia UniversityModerator:FrancesEnglish,PSC/AFTGroup C:THEINDUSTRIALMODELCOLLECTIVE mics, University of San FranciscoDiscussant:Stephen L. Finner, Director, NortheastRegion AAUPModerator:Bernard Mintz, Executive Assistant tothePresident,WilliamPatersonCollege of New sorofBaruch ChapterOFACADEMICTuesday Morning, April 27, 19829:00SMALL GROUP SESSIONSGroup D:THE USE AND ABUSE OF nagement/ConfidentialAffairs,NYSGovernor's Office of Employee RelationsNuala McGann Drescher, PresidentUnited University ProfessionsModerator:Samuel Ranhand, Professor of ManagementBaruch College, CUNY3

Group E:MANAGERIALDISCRETION,FINANCIALEXIGENCY AND REDUCTION IN FORCESpeakers:James Begin, Director, Institute forManagementandLaborRelations,Rutgers orManagement and LaborRelations, Rutgers UniversityTheodore Settle, Assistant Professor,Institute forManagement and LaborRelations, Rutgers University11:001:00Moderator:David Newton, Vice ChancellorLong Island UniversityGroup F:WHATEVER HAPPENED TO ACADEMIC FREEDOM?Speaker:Victor w.Sim,Secretary, CAUTDiscussant:Joyce Barrett, Esq., Baruch CollegePSC/CUNY Office of Legal dent, Faculty and Staff Affairs,Baruch College, CUNYAssociateExecutivePLENARY SESSION IIIA DECADE OF CAMPUS her Education, Pennsylvania StateUniversityDiscussant:Gene Maeroff,York TimesModerator:Robert T. Simmelkjaer, Dean, School ofGeneral Studies, City College of NewYork, CUNYEducationWriter,NewLUNCHEON SYMPOSIUMPERSPECTIVES:THE STATE OF THE ART -- THEN AND NOW4

Speakers:Joel M. Douglas, Director, College,CUNY,Former Dir., NCSCBHEAaron Levenstein, Professor EmeritusBaruch College, CUNY, Former Assoc.,Dir., NCSCBHEPThomas Mannix, Director of a Systemwide, Former ActingDir., NCSCBHE3:30SUMMATIONJoel M. DouglasA word About the National CenterThe National Center is an impartial, nonprofit educationalinstitution serving as a clearinghouse and forum for thoseengaged in collective bargaining (and the related processes universities.Operating on the campus of Baruch College, CityUniversity of New York, it addresses its research to scholarsand practitionersin the field.Membership consists ofinstitutions and individuals from all regions of the U.S. andCanada.Activities are financed primarily by membership,conference and workshop fees, foundation grants, and incomefrom various services and publications made available tomembers and the public.Among the activities are:The two-day Annual Spring ConferencePublication ofthe proceedings ofthe AnnualConference, containing texts of all major papers.IssuanceofanAnnualDirectoryContracts and Bargaining gOfinFacultyHigherThe National Center Newsletter, issued five times ayear,providingin depth analysis oftrends,current developments major decisions of courts andregulatory bodies, updates of contract negotiationsand selection of bargaining agents, reviews andlistings of publications in the field.5

Monographs - complete coverage of a major problemor area, sometimes of book length.Regional workshops, using a hands-on format toprovide training in subjects like negotiating mentation and administration of contracts.Elias Lieberman Higher Education Contract Librarymaintained by the National Center, containing g agreements, and important books andrelevant research reports.BRAIN (Baruch Retrieval of Automated Informationfor Negotiations), a Contract Data Bank maintainedjointly with McGill University,providing forretrieval and analysis of specific tion,housed atthe National Center andestablished with the cooperation of the AmericanArbitration Association.AcknowledgmentsThe Proceedings of the Annual Conference continue to beviewed as an update on the state-of-the art in academiccollective bargaining.we at the Center are proud of theacceptability that this publication has received. The staff ofthe National Center deserve full credit for the preparation ofthis publication.The speeches were transcribed by IsabelGonzalez.The proofing was coordinated by Ruby N. Hill,assisting her were Carol Rosenberg and Lorraine DeBona,graduate assistants of the National Center and Lisa Flanzraich,librarian of the National Center.As she has done since theinception of the National Center, Evan G. Mi tchel:l suprvisedthe entire project from start to finish.The Baruch wordProcessing Center assisted in manuscript production. To all ofthe above, I am indeed thankful.-J.M.D.6

2. CAMPUS BARGAINING AND THE LAW: A DECADE OFHIGHER EDUCATION COLLECTIVE BARGAINING -1972-1982June M. WeisbergerProfessor of LawUniversity of Wisconsin Law SchoolAs any serious observer of the higher education academiccollective bargaining scene today knows, this area of laborrelations law is the most complex.It is most complex becauseit requires knowledge of both the traditional and the rapidlychanging higher education academic setting as well as generaland specific labor relations law under the National LaborRelations Act as amended.It also requires knowledge of nistrative agency decisions governing public sector laborrelations in a number of different jurisdictions. In addition,a knowledgeable practictioner in this area should also be awareof the patchwork quilt of other but very important relateddevelopments under Title VII, under the Equal Pay Act, and evenunder a constitutional law analysis, where appropriate.Allthese areas are not part of traditional labor relations law,but they affect both directly and indirectly the general areaof employment relationships in higher education.Major laborrelations-legal developments of the past. decade and themesaffecting higher education faculty will be viewed in thefollowing pages not in technical legal terms, such as specificrepresentational or scope of bargaining decisions, but in verybroad terms.Five topics containing relevant labor relationsand employment law information will be discussed below .!.The first topic involves student participation in facultycollective bargaining in higher education and the developingstatutory law.In the early seventies there were certainexperiments by agreement of the parties involving versitycollective bargaining.The most well-publicized ersitiesresulting in several innovative and interesting state statutoryschemes.Starting first in Montana in 1975 and continuing inOregon, Maine and Florida,there are now four differentstatutory modelsl concerning student participation in somefashion at the collective bargaining table. Montana, the firstattempt, produced a bill that received support from not onlythe Montana student body lobby, the AFT, but eventually thestate higher education commission.In the Montana scheme,student participated in the management caucus as well as beingpermitted by statute to act as observers at the collectivebargaining table.The next statutory experiment was that enacted in Oregonin 1975.This legislation is perhaps the most perplexingbecause under Oregon state statute student representatives arepermitted "to comment in good faith during the bargainingsessions on matters under consideration" and are allowed "tomeet and confer" (the phrase used in the NLRA to mean bargaincollectively) with the exclusive faculty representative and thepublic employer regarding the terms of any agreement betweenthem prior to execution of a written agreement incorporating7

the parties' understandings.In 1977, Florida gave students the right to comment toboth parties and to the public during negotiations regardingthe impact on the "educational environment," the phrase used inthe legislation. Also, students were permitted "to participatein good faith" during all negotiations.In 1979,the Maine Legislature provided forstudentrepresentatives to meet and confer with university bargainersduringthe negotiations and with both parties priortobargaining.These various experimentshavenotfoundwidespreadsupport elsewhere yet and, therefore, many may think that thisis an interesting development but one of academic interestonly.I suggest that this topic may be one where there may berenewed legislative interest.While there is no widespreadmovement yet to follow the four jurisdictions where ntrepresentatives during faculty bargaining, rapidly escalatingstudent costs may renew student interest and thus pressure onlegislatures for additional experiments in other jurisdictionsthat either parallel or deviate in some interesting way fromthese first four models.If there are to be additional legislative experiments anda following of the pattern in part or in whole of these fourjurisdictions, additional issues will have to be dealt with inthe legislation.There are already interesting variations inthe four jurisdictions not only as to the roles of the studentrepresentatives, but also 1) how student representatives arechosen,2)what access students will have to documentsexchanged by the parties during collective bargaining andduring any impasse procedures, and 3) the important question ofconfidentiality of the collective bargaining process.IIThe second topic to be addressed has just recently gainedattention.It has to do with tenure review deliberations andvotes by faculty.The question specifically is, "Is there anacademic freedom privilege which will insulate the decisionmaking process when the decision is challenged in a variety offorums and the vote of the participants is alleged to be acritical element of a complainant's case?" So far the law hasgiven us no clear-cut answer.We have two very differentapproaches demonstrated by two federal courts in 1981.Thecases involve the City University of New York2, on the onehand, and the University of Georgia,3 on the intment with tenure by one of the community collegeswithin the City University of New York system.It was acediscrimination.During discovery, the complainant sought thevotes of two named defendants in the peer review process whichled to that adverse tenure decision.The individual defendantsrefused to answer citing an academic freedom privilege.The8

court upheld the asserted privilege that was put forth by thedefendants noting that academic freedom, in the judgment ofthat court, is a transcendent value which encompasoes theconcept of peer review by secret ballot. Thus, the decision isisolated from improper pressures.In addition, the court saidthat equivalent evidence might be had in other ways so as notto reveal the voting.Societal interest in protecting thesecret ballot,in that court'sjudgment,outweighed thecomplainant's right to discover the individual votes of the twonamed defendants.In another case involving somewhat similar c rcumstances,the trial court and the appellate court went in differentdirections.In the case involving the University of Georgia,the plaintiff alleged Title VII sex discrimination in thedecision of the University not to promote her to an associateprofessorship.During pre-trial activities to depose variousother participants in the tenure decision vote, ProfessorDinnan refused to divulge his vote in that review process.Upon motion, the court attempted to compel his testimony and heagain refused.He was cited for contempt and jailed.TheFifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court'sfinding that Professor Dinnan was indeed in contempt of court.It concluded that society's value in discovering the truthoutweighed the privilege that the defendant attempted to assertin his particular case.It rejected the type of analysis thatthe New York federal district court engaged in the CityUniversity of New York case.Given these two diverse answers to this particular problemarea of conflicting societal values, this question will nodoubt be repeatedly litigated until some more definitive answeris given to this perplexing balancing problem arising under theConstitution, under Title VII, or under various other forms ofprotective legislation.The required balancing processing iscertainly not an easy one to resolve on the merits or topredict the eventual outcome.IIIThe third area identified as a major and troublesome oneof legal developments during the past decade involves thequestion of financial exigency and the courts.It is dconstraints become more and more pressing for a large number ieldCollege developments4 have been studied to see what light hasbeen shed upon the problem of how courts will approach tenuredfaculty layoffs in the context of a university's argument offinancial exigency.Over the past .ten years, shrinking financial resources ofuniversities have threatened the traditional institution offaculty tenure.The main legal questions are:1) Under thecircumstances does financial exigency exist? and 2) What is theproper role of the courts in judging the existence of financialexigency?In this critical area, the developing case lawprovides answers.First,it is known from the case law that the financial9

exigency must be a bona fide one.If almost immediatelyfollowing the layoff or discharge of tenured faculty newfaculty or replacements are hired, the financial exigencydefense of the university or college will be seriouslyquestioned.If there are related developments that do not godirectly to financial exigency but appear to be an attack onthe basic institution of tenure, the financial exigency claimedby the institution of higher education will be viewed assomething less than bona fide.(One example is the one-yearterminal contract that the Bloomfield College administrationattempted to impose on other faculty members.) As a result ofthe appellate court decision in Bloomfield ColleI,e and othercases, it is also known that a court will proba ly not viewspecific financial decisions of university decision-makers as acritical determinant in whether there is a bona fide financialexigency.It is known what type of evidence courts have beenparticularly impressed with in determining whether a bona fidedecision of financial exigency has been made.For ecurringoperating deficits.There is another interesting, andas yet unresolvedquestion.In looking at evidence of recurring operationaldeficits, is the appropriate universe the entire universitystructure or may proof of operating deficits relating only toone program or one department be sufficient to prove that abona fide financial exigency exists?There are also some constitutional dimensions in this areaof the law that have produced some interesting judicialdecisions.One obvious conclusion to be drawn is that adecision finding financial exigency cannot be used as a pretextfor violating a constitutional right (or a statutory orcontractual right.)Other constitutional developments relate to the proceduraldue process that may be required in deciding which faculty tolay off once the determination of bona fide financial exigencyhas been made.In an interesting case in the Western Districtof Wisconsin, Johnson v. Board of Regents of the University esting analysis and set forth guidelines for certainminimal procedural due process rights that faculty members havein what he characterized as a non-adversarial setting. As thedecision indicates, these are not full due process, ludecrossexamination, etc.In addition, there are minimum standards ofequity that certain courts have pointed to requiring "uniformprocedures" with reasonable standards" to determine whichfaculty to lay off.There is a related and interesting question in thefinancial 'exigency, lay-off area as to whether a university hasan obligation to make feasible efforts to find the adverselyaffected tenured faculty member alternative employment.Thisapproach, imposing upon the university an additional burden notonly to prove the bona fideness of the financial exigency butto take affirmative action to provide alternative employment,10

igations.It has not found judicial support but, I suggest,that there might very well be additional cases brought topressure the parties to have this type of affirmative actionincorporated explicitly or implicitly in lay off procedures.There is currently a debate going on as reported in theChronicle of Higher Education.6These news stories concernwhether university decision makers have a broad power to layoff tenured faculty when there is no financial exigency butwhen management believes programmatic changes are desirable ina whole variety of circumstances.Courts may increasingly bewilling to define financial exigency broadly and to accept awide variety of evidence and proof of what is a financialexigency.As to whether the courts will go beyond this,however, and define financial exigency to include programmaticchanges as a basis for laying off tenured faculty, requires abig judicial leap.That leap will only be taken where theprogrammatic changes are not solely a result of a managementdecision to change the direction of the enterprise but adecision reflecting faculty input, perhaps in the form of rticles of the Chronicle of Higher Education indicate this tobe highly controverted area.Laying off of tenured faculty forprogrammatic changes in contrast to afinancial exigencyargument (even one very broadly or liberally defined) is a newlegal argument and one,that courts willlook at verythoughtfully and with cialreluctance to intrude on the academic decision making processand how courts should handle "mixed motive," adverse personneldecisions.Over the past decade many courts have frequently expressedtheir desire to leave tenure and other personnel decisionsinvolving higher education faculty untouched despite challengesbased upon allegations of discrimination, interference withprotected activities or contract violation.Courts have beenvery ready to acknowledge their lack of qualifications to makethese decisions and initially at least accorded significantweight and value to the academic peer review process by whichthese decisions are made.The most often cited case demonstrating extreme judicialreluctance to interfere with the peer review process is Faro vNew York University7, a 1974 Second Circuit Court of Appealsdecision.The reluctance demonstrated by the court in Faro andby other courts in other decisions ·suggests that theacademic higher education setting,normal rules inationandappropriate remedies might have different outcomes.Indeedthat has been the trend of cases decided at the beginning ofthe decade under study.The current trend, however, appears to modify that earlyreluctance by courtsto interfere with academic decisionmaking.Relatively recently the Second Circuit, the same court11

that decided Faro, had this to say:"We fear, however, thatthe common-sense position we took in Faro, namely that courtsmust be ever mindful of relative institutional competences, hasbeen pressed beyond all reasonable limits, and may be employedto undercut the explicit legislative intent of the Civil RightsAct of1964."This quotation comesfrom aTitle VIIdiscrimination case involving Syracuse UniversityB and is anexpress acknowledgement by the Second Circuit that its earlierstatement giving heavy weight to the academic peer reviewprocess due to the special competence of institutions of highereducation (and not courts) seriously influenced a number ofjudicial decisions following the Faro decision.There has been a decided reluctance to grant tenure as nstitutional or statutory law in academic settings.In arecent case involving Muhlenberg College, 9 however, the courtdemonstrated no such reluctance where the faculty reviewcommittee had recommended tenure but that tenure decisionrecommendation by the committee had not been implemented by theadministration.Admittedly, this is not a difficult case inwhich to grant tenure as an appropriate remedy. However, it isclearly a step away from that earlier reluctance to interferein any way with the academic decision making processes ofhigher education.Similarly, in "mixed motive" cases where adverse personneldecisions have been made and the plaintiff or complainantalleges that a "bad" or impermissable reason was the basis forthe decision while the institution defends by pointing to abona fide reason,institutions are at least required ouncements by the United States Supreme Court in thecontext of mixed motives cases. They also reflect some backingaway from earlier, heavy deference accorded to institutions ofhigher education in their personnel judgments.Two casesdecided by the Su8reme Court, Mount Healthy City SchoolDistrict v. Doyle, 1a yublic school case, and Keene StateUniversityv.Sweeney, 1ahighereducationcasearerelevant.In Mount Healthy, there is some formulation of howcourts should handle cases where either the allegation is madethat the reason given by the university is a pretext forprohibited or improper decision making or several reasonscontributed to the adverse decision and at least one wasimproper.In Mount Healthy the Supreme Court tells the parties tion institutions' adverse personnel decision.Then theburden to produce additional evidence (but not the burden ofpersuasion) shifts.At that point, the institution of highereducation has to demonstrate that the same decision would havebeen made in the absence of the protected (constitutional,statutory or contractual) activity.There are some who believethat in the higher education setting the Mount Healthy analysis(where the burden is first allocated to the plaintiff or thecomplainant to make a prima facie case and then shifts to theinstitution to defend the action by producing proof that tt:iatsame decision would have been made even if the improper motivehad not been part of the picture) has been changed by the 1978United States Supreme Court decision in Board of Trustees of12

Keene State College v. Sweeney.It has been suggested that a very careful reading of theper cur iam decision does not change thE Mount Healthy analysisand that Mount Healthy is alive and well whether you aretalking about an adverse personnel decision by a public schoolsystem, by a municipality or by an institution of highereducation

Joel Segall, President, Baruch College, CUNY 9:30 PLENARY SESSION I CAMPUS BARGAINING AND THE LAW Speaker: Moderator: June M. Weisberger, Professor of Law, University of Wisconsin Law School Aaron Levenstein, Professor Emeritus Baruch College, CUNY, Former Assoc. Dir., NCSCBHEP 11:00 PLENARY SESSION II