Transcription

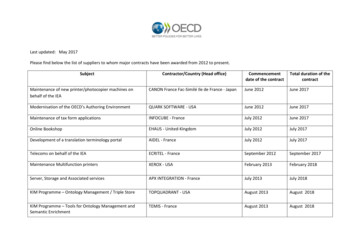

July 6, 2017William HinmanDirector, Division of Corporate FinanceBrent J. Fields, SecretarySecurities and Exchange Commission100 F Street, N.E.Washington, DC 20549Dear Mr. Hinman:The Human Capital Management Coalition (the “HCMCoalition”) respectfully submits this petition for rulemakingpursuant to Rule 192(a) of the Commission’s Rules of Practice. 1As representatives of the HCM Coalition, a group ofinstitutional investors with 2.8 trillion in assets, we requestthat the Commission adopt new rules, or amend existing rules,to require issuers to disclose information about their humancapital management policies, practices and performance.There is broad consensus that human capitalmanagement is important to the bottom line, and a large bodyof empirical work has shown that skillful management ofhuman capital is associated with better corporate performance,including better risk mitigation. We view effective humancapital management as essential to long-term value creationand therefore material to evaluating a company’s prospects.Requiring disclosure regarding human capitalmanagement would fulfill the Commission’s core mission ofinvestor protection; satisfy Congressional mandates to promoteefficiency, competition and capital formation; and serve thepublic interest, for the following reasons: Given the key role of human capital, investorsunder current Commission disclosurerequirements cannot adequately assess acompany’s business, risks and prospects, forinvestment, engagement or voting purposes,without information about how it is managing itshuman capital.Greater transparency would allow investors tomore efficiently direct capital to its highest valueuse, thus lowering the cost of capital for wellmanaged companies.Rules of Practice and Rules on Fair Fund and Disgorgement Plans, section192(a) (Sept. 2016)(available at f).1

2 Consistent mandatory disclosure standards wouldobviate the need for issuers to respond to amultitude of investor requests for human capitalrelated information; make that information easierfor all investors to collect and analyze; and levelthe playing field for investors that are not largeenough to demand or otherwise accessindividualized disclosure.There is broad consensus that long-term investingstrategies are needed to stabilize and improve ourmarkets and to effect the efficient allocation ofcapital. Human capital management metrics areprecisely the type of information that enablesinvestors to take the long view.In the last section of this petition, we suggest keycategories of information that we believe are fundamental tofurthering investors’ understanding of how well a company ismanaging its human capital. These categories include:workforce demographics; workforce stability; workforcecomposition; workforce skills and capabilities; workforceculture and empowerment; workforce health and safety;workforce productivity; human rights; and workforcecompensation and incentives.The HCM Coalition is a collaborative effort among aglobal group of institutional investors to further elevate humancapital management as a critical component in companyperformance and in the creation of long-term shareholdervalue. More information on the HCM Coalition and itsmembers is available here. In the main body of this letter, weprovide detailed evidence that supports our belief that humancapital is a company’s most valuable asset and that stewardinghuman capital with that in mind will help to preserve and addvalue.Human Capital and Value CreationOver the past several decades, the importance of humancapital to corporate value creation has surged. There is broadagreement that human capital encompasses the knowledge,motivation, skills and experience of a company’s workforce, aswell as its alignment with the company’s mission and values. 2See, e.g., Gary Becker, The Age of Human Capital, at 3 (2002) (“Humancapital refers to the knowledge, information, ideas, skills, and health ofindividuals.”); National Association of Pension Funds, “Where is theWorkforce in Corporate Reporting,” at 8 (June 2015)2

3As the global economy has become more knowledgeintensive and competitive, companies are under increasingpressure to adapt to new technologies and differentiatethemselves. 3 Human capital is responsible for innovation, aswell as effectively managing and carrying out companies’ dayto day work—whether that is shelving goods at a store, caringfor hospital patients, repairing equipment or investing assetsto provide retirement benefits for its employees.Human capital is thus key to getting and maintainingcompetitive advantage. Former Secretary of Labor RobertReich asserted, “The only unique assets that a business has forgaining competitive advantage over its rivals are the skills anddedication of its employees.” 4 One influential finance scholarhas characterized human capital as firms’ “most valuableasset.” 5Companies and their leaders recognize the paramountimportance of human capital. Global CEOs surveyed byPricewaterhouseCoopers in 2015 identified “availability of keyskills” as the second most worrying risk, ahead of geopoliticaluncertainty, tax burden and shift in consumer spending andbehaviors. 6 Kevin Ryan, founder and CEO of Gilt Group, put itthis way:Of all the duties facing a CEO, obsessing over talentprovides the biggest return. Making sure that reporting-An-NAPF-discussion-paper.aspx).3 E.g., Bo Hansson, “Employers’ Perspectives on the Roles of HumanCapital Development and Management in Creating Value,” at 7, Apr. 2006("As economies continue to become more global and technological changecontinues to favour the highly educated and skilled, the already-significantrole of human capital is likely to 530787.pdf)4 ployee-experiences; seealso Michael Adelowotan, "The Significance of Human Capital Disclosuresin Corporate Annual Reports of Top South African Listed Companies:Evidence From the Financial Directors and Managers”, Afr. J. Bus. Mgmt.,Vol. 7(34), 3248-58 (2013), at 3249 (“Human capital is an asset that canprovide a source of sustained competitive advantage because they are oftendifficult to imitate [citation AJBM/article-full-textpdf/61F9D6E20836).5 Luigi Zingales, “In Search of New Foundations,” The Journal of Finance,Vol. LV, No. 4, 1623-1653 (Aug. 2000), at pers/research/search.pdf).6 PricewaterhouseCoopers, “18th Annual Global CEO Survey,” at 9 ).

4environment is good, that people are learning, and thatthey know we’re investing in them every day—I’mconstantly thinking about that, yet I still don’t feel I’mdoing enough. If CEOs did absolutely nothing but act aschief talent officers, I believe, there’s a reasonablechance their companies would perform better. 7Materiality of Human Capital ManagementThe importance of human capital is supported bydecades of research. A large body of empirical work has shownthat thoughtful management of human capital is associatedwith better corporate performance, including risk mitigation.Research has shown that differences in human capitalmanagement performance can form the basis for successfulinvestment strategies. Studies by Laurie Bassi, former directorof research at the American Society for Training andDevelopment, show that stock selection using training andother human capital management practices can producesuperior investment outcomes. Two portfolios of largecapitalization companies launched in 2001 and 2003 usingcriteria related to training and employee developmentoutperformed the S&P 500 on an annualized basis by 3.1% and4.4%, respectively, through May 25, 2010. 8 Four otherportfolios launched in 2008, selected using a wider variety ofHCM factors including commitment to talent management alsooutperformed the S&P 500 through May 25, 2010 on anannualized basis to varying degrees, from .1% to 11.9%. 9Similarly, investing in companies identified as desirableworkplaces can generate superior returns. A study byWharton’s Alex Edmans found that investing in a valueweighted portfolio of companies in the Fortune 100 America’sBest Companies to Work For from 1984 through 2009generated excess risk-adjusted returns of 3.5% per year. 10Kevin Ryan, “Gilt Group’s CEO on Building a Team of A Players,”Harvard Business Review, Jan.-Feb. 2012 (available ding-a-team-of-a-players).8 Laurie Bassi & Dan McMurrer, “Human Capital Management PredictsStock Prices,” at 1 (June MPredictsStockPrices.pdf)(hereinafter, “Bassi & McMurrer Stock Prices”).9 Bassi & McMurrer Stock Prices, at 1.10 Alex Edmans, “Does the Stock Market Fully Value Intangibles,” Journalof Financial Economics, Vol. 101, 621-640 (2011), at 621(http://faculty.london.edu/aedmans/Rowe.pdf).7

5A recent report by the Harvard Law School Pensions andCapital Stewardship Program reviewed 92 studies thatmeasured performance using metrics of value to investors,such as total shareholder return, return on assets, return oncapital, profitability and Tobin’s Q. 11 The Harvard Reportfound that in a majority of studies human capital managementpolicies were associated with better financial performance. 12Many academic studies have concluded thatcombinations or bundles of policies and practices affect firmperformance, and significant attention has been paid to theimpact of a “high-performance” or “high commitment”workplace. Although there is no single definition, these arepolicies and practices designed to reduce turnover, encouragegreater employee commitment and motivation and enhanceemployee skills.For example, Mark Huselid analyzed a group of highperformance workplace practices and determined that suchpractices are associated with lower turnover as well as betterproductivity and firm financial performance. Specifically, thestudy found that certain combinations of high-performanceworkplace practices were associated with statisticallysignificant increases in productivity, Tobin’s Q and gross rateof return on capital. 13 Similarly, Huselid and Barry Beckerfound that high performance workplace practices have astatistically significant positive effect on firm performance. 14More recent scholarship has found that specialized highperformance workplace practices enhanced performance inAaron Bernstein and Larry Beeferman, “The Materiality of HumanCapital to Corporate Financial Performance,” Pensions and CapitalStewardship Project, Labor and Worklife Program, Harvard Law School,Apr. y%20April%2023%202015.pdf).12 Bernstein & Beeferman, at 12.13 Mark Huselid, “The Impact of Human Resource Management Practiceson Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance,” Academyof Management Journal, at 645-47 (1995), at 995 AMJ HPWS Paper.pdf).14 Mark Huselid & Brian Becker, “The Strategic Impact of HighPerformance Work Systems,” at 2 (Aug. 25, 995 Strategic Impact of HR.pdf); see also Brian Becker & Barry Gerhart, "The Impact of HumanResource Management on Organizational Performance: Progress andProspects,” Academy of Management Journal Vol. 39, No. 4, at 797 (1996)("In sum, at multiple levels of analysis there is consistent empirical supportfor the hypothesis that HR can make a meaningful difference to a firm'sbottom line.”) (amj.aom.org/content/39/4/779.short?rss 1&ssource mfr).11

6interdependent work settings by supporting the relationshipsamong roles needed to carry out tasks effectively. 15There is evidence that training can positively affectcorporate performance. The Harvard Report reviewed 36studies, of which 22 found that training was “associated onlywith superior investment outcomes.” 16 Other overviews ofstudies have found ample evidence that the provision oftraining or higher training expenditures is linked to betterperformance on intermediate measures, such as productivityand customer satisfaction, as well as financial performance. 17Some of the studies reviewed measured performance in yearssubsequent to the years in which training was measured, toaddress the question of causation.Research by Zeynep Ton, an expert on operationsmanagement, suggests one avenue by which training mayimprove performance in retail. Ton’s research has found thathigh-performing retailers use cross-training to provideflexibility and address variability in demand—thus bettersatisfying customers--without resorting to practices like lastminute (“just-in-time”) scheduling and extremely short shiftsthat lead to higher turnover and lower motivation. 18Ton’s research also showed that cutting labor hours, acommon strategy among retailers looking to control expenses,often backfires in the form of reduced profitability. Tonobtained store-level data for over 250 Borders bookstores from1999 through 2002 and analyzed their spending on labor; shefound that increasing labor spending resulted in higher profitmargins or, put another way, that increased labor costsJody Hoffer Gittell et al., “A Relational Model of How High-PerformanceWork Systems Work,” Organizational Science, Vol. 21, No. 2 79?seq 1#page scan tab contents).16 Bernstein & Beeferman, at 10.17 Hansson, at 19-23 ("In one of the few U.S.-based studies that analyzedactual training expenditures, a recent analysis of financial institutionsconducted for the American Bankers Association (2004) found that thosefinancial institutions with higher-than-average training expenditures peremployee subsequently had better outcomes than other institutions on fivekey financial measures examined: return on assets, return on equity, netincome per employee, total assets per employee, and stock return.”); LaurieBassi et al., “Profiting From Learning Firm-Level Effects of TrainingInvestments and Market Implications, Singapore Management Review, Vol.24, No. 3, 61-76 (2002), at al-Singapore-2002.pdf).The author of the first overview noted that few training studies had beendone on U.S. companies due to data constraints.18 Zeynep Ton, The Good Jobs Strategy, 138-148 (2014).15

7generated sales increases large enough to raise overallprofitability. 19 Understaffing led to “phantom stockouts,” wherea product is in the store but cannot be located for the customer,bungled promotions, theft and spoilage. 20 Similar conclusionswere reached in a study by Vidya Mani and two colleagues,who found systematic understaffing during peak hours at 41retail stores and estimated that appropriate staffing wouldimprove profitability by 5.74%. 21 Managing human capital bytreating it solely as an expense to be minimized, then, candepress performance in retail.Employee engagement, which many employers measure,has also been found to have a positive association with firmperformance. Definitions of employee engagement vary, but itis generally agreed to include the strength of an employee’scommitment to the employer and the employee’s willingness toexpend effort in his or her role. 22The reciprocal nature of employee engagement—itsdependence on employer as well as employee commitment—differentiates it from employee satisfaction. Consultant AonHewitt has emphasized the need for senior leaders to create a“culture of engagement.” 23 As one author put it, “The degree towhich employee engagement technology translates into ahappier, more productive workforce, however, may depend oncompany culture and management’s willingness to examineand act on its own shortcomings.” 24An analysis of 50 global firms by Towers Watsondetermined that the average one-year operating margins ofcompanies with low engagement scores trailed those atcompanies with high “sustainable engagement” scores by 17Ton, at 38-40.Ton, at 40.21 Vidya Mani et al., “Estimating the Impact of Understaffing on Sales andProfitability in Retail Stores,” Production and Operations Management,Vol. 24, No. 2, 201-218 (2015) ns/understaffing.pdf).22 Dinah Wisenberg Brin, “Technology for Employee Engagement on theRise,” Society for Human Resource Management (Feb. 9, ementRising.aspx).23 Aon Hewitt, “2015 Trends in Global Employee Engagement,” at 4 ent-Report.pdf).24 Gemma Richardson-Smith and Walter Bappert, “Employee Engagement:A Review of Current Thinking,” Institute for Employment Studies, at 14(2009); Brin.1920

8percentage points. 25 A 2002 meta-analysis found that higheremployee engagement is associated with higher customersatisfaction and loyalty, productivity and profitability, as wellas lower turnover. 26 Aon Hewitt estimates that a 5% increasein employee engagement leads to a 3% increase in revenuegrowth the following year. 27A case study by the Human Capital ManagementInstitute (HCMI) found that Jet Blue locations and flights witha higher average “net promoter score”—a measure of how likelyan employee is to recommend Jet Blue as an employer (oftenused in lieu of employee engagement measures)—had highercustomer satisfaction and revenue. The HCMI estimated that a5% increase in net promoter score was associated with a 1%increase in revenue. 28Further, board and workplace diversity has been linkedto financial performance. A growing body of empirical researchindicates a significant positive relationship between firm valueand the percentage of women and minorities on boards. A 2012Credit Suisse Research Institute evaluated the performance of2,360 companies globally over six years and found thatcompanies with one or more women on boards delivered higheraverage returns on equity, lower leverage, better averagegrowth and higher price/book value multiples. 29 A 2015McKinsey study of 366 companies found that corporateleadership in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversitywere 35 percent more likely to have financial returns abovetheir national industry median. 30Human capital management matters not only when itconfers competitive advantage and improves firm performance.Material risks related to human capital management canTony Schwartz, “New Research: How Employee Engagement Hits theBottom Line,” Harvard Business Review, Nov. 8, employee.html).26 James K. Harter et al., “Business-Unit-Level Relationship BetweenEmployee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: AMeta-Analysis,” Journal of Applied Psychology Vol. 87, No. 2, 268-79 7 Harter.pdf).27 Aon Hewitt, at 1.28 o-engagementlinkage-case-study/.29 Credit Suisse, “Does Gender Diversity Improve Performance?” Jul. 31,2012 mprove-performance.html)30 Vivian Hunt, Dennis Layton & Sara Prince, “Diversity Matters,”McKinsey & Company, Feb. 2, iversity%20Matters.pdf)25

9create substantial risks for companies and investors, damagingcorporate reputation, generating legal liabilities andundermining relationships with key stakeholders.Human capital-related risks are not limited to acompany’s direct employees. Major shifts in the organization ofwork over the past several decades, including the rise ofoutsourcing, subcontracting, franchising and complex globalsupply chains, have multiplied those risks. When a company’sproducts or services are made or provided by its employees,that company has control over the work and, as a generalmatter, liability for legal violations related to it. Asemployment relationships are increasingly supplanted bycontractual ones, there is a growing concern that the incentivesof the company’s contracting partners are not necessarilyaligned with those of the company. This misalignment maylead to financial and reputational damage. 31It is not unusual for there to be multiple layers ofcontractors and subcontractors whose employees produce goodsor provide services for a firm and who may be spread out acrossmultiple countries or geographic regions. Generally, thefurther down the chain one goes, the greater the incentives areto cut corners through nonpayment of owed wages, safetyshortcuts and other violations. 32 A company’s ability to controlhow work is performed on its behalf depends on clearperformance standards and robust monitoring, enforcementand coordination mechanisms; falling short on any of these canhave serious consequences. For example, investigators haveconcluded that BP’s 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion and oilspill, which killed 11 workers, cost shareholders billions andreleased nearly five million barrels of oil into the Gulf ofMexico, 33 resulted from, among other things, the lack of hazardassessment coordination between BP and the contractoractually operating the drilling rig. 34See, e.g., David Linich, “The Path to Supply Chain Transparency: APractical Guide to Defining, Understanding, and Building Supply ChainTransparency in a Global Economy,” at 2 (2014) (“The dispersed nature oftoday’s supply chains creates increasing levels of risk for multinationalbusinesses, making transparency both critical and us-en/articles/supply-chaintransparency/DUP785 ThePathtoSupplyChainTransparency.pdf)32 David Weil, “How to Make Employment Fair in the Age of Contractingand Temp Work,” Harvard Business Review, Mar. 24, 2017.33 Campbell Robertson & Clifford Krauss, “Gulf Spill is the Largest of itsKind, Scientists Say,” The New York Times, Aug. 2, html).34 See U.S. Chemical Safety Board, “CSB Investigation: At the Time of 2010Blowout, Transocean, BP, Industry Associations, and Government Offshore31

10Candy maker The Hershey Company (Hershey) wasblindsided in 2011 when a subcontractor of a subcontractor ofHershey’s packing facility contractor used an educationaltravel program to bring foreign students to the U.S. to packand move heavy boxes. Eventually, the students staged apublic walkout to protest working conditions, the deduction offees and inflated rent from their paychecks and the fact thatthey were required to continue working at the facility in orderto maintain their educational travel visas. 35 Hershey, itspacking facility contractor Exel, and Exel’s staffingsubcontractor SHS all claimed not to know about the students’plight, since the student workers were provided by yet anothersubcontractor, raising questions about the adequacy of thefirms’ oversight of their staffing providers. 36Evolving norms are calling for more due diligence andtransparency on human capital risks in the supply chain. A2010 Harvard Business Review article noted, “Consumers,governments, and companies are demanding details about thesystems and sources that deliver the goods.” 37 Regulators haveresponded by instituting measures that encourage attention tothese risks. In the United Kingdom (U.K.), the Modern SlaveryAct requires larger businesses to prepare a “slavery andhuman trafficking statement” for each fiscal year, confirmingthat the firm has taken steps to ensure that slavery andhuman trafficking is not taking place in any of its supplychains and in any part of its own business. The firm can,alternatively, state that it has taken no such steps. 38 InCalifornia, the Transparency in Supply Chains Act requiresthat large companies doing business in California disclose their“efforts to eradicate slavery and human trafficking from [their]direct supply chain for tangible goods offered for sale,”Regulators Had Not Effectively Learned Critical Lessons From 2005 BPRefinery Explosion in Implementing Safety Performance Indicators,” July24, 2012 -indicators/).35 Julia Preston, “Foreign Students in Work Visa Program Stage Walkoutat Plant,” The New York Times, Aug, 17, html).36 Dave Jamieson, “Student Guestworkers at Hershey Plant AllegeExploitative Conditions,” The Huffington Post, Aug. 17, ent-guestworkers-athershey-plant n 930014.html).37 Steve New, “The Transparent Supply Chain,” Harvard Business Review,Oct. 2010 ain).38 See n/54/enacted.

11including certification, audits, verification, internalaccountability and training. 39Current Lack of Comparable Data on Human CapitalDespite the importance of human capital management tocompany performance, human capital is nearly invisible in theCommission’s disclosure rules. Regulation S-K, which setsforth disclosures required in registration statements andvarious reports under the integrated disclosure system,contains one item related to human capital: Item 101(c)(xiii), inthe “Narrative Description of Business” section, mandatesdisclosure of the “number of persons employed by theregistrant.” 40Companies often make mention of human capital-relatedrisk factors in periodic filings with the Commission; thesedisclosures, however, tend to be boilerplate, designed to limitliability rather than convey meaningful information abouthuman capital management practices. A study by theSustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) found thatmore than 40% of all 10-K disclosures on sustainability topicswere boilerplate and that lack of standardization limited theutility of the 15% of disclosures that used metrics. 41 Boilerplatedisclosures are not only unhelpful to investors; there is someevidence that vague risk factor disclosures are construednegatively by the market, leading to higher costs of capital. 42Surveys conducted by environmental, social andgovernance (ESG) data providers do not solve these problems.Many companies are overwhelmed with disclosure requestsand limit their responsiveness, often to the largest investors. 43Even if an investor or data provider asks for uniformKamala Harris, The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act: AResource Guide, at I /resource-guide.pdf).40 https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/229.101.41 Comment of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board on “ConceptRelease: Business and Financial Disclosure Required by Regulation S-K,”dated July 1, 2016 df)(hereinafter, “S-K Concept Release”).42 Ole-Kristian Hope et al., “The Benefits of Specific Risk-FactorDisclosures,” at 11 (Feb. 26, 2016) (“greater specificity in risk factordisclosure reduces the variance uncertainty premium and thus the expectedcost of m?abstract id 2457045).43 E.g., Mike Hower, “Could Sustainability ‘Survey Fatigue’ Launch a 1Billion Industry?” Greenbiz, Apr. 2, -cuts-core-esg-research-andratings).39

12information from all companies it surveys, responses may beincomplete, may not adhere to the requested format and maycalculate metrics differently, making it difficult to comparecompanies across industries and markets.Some companies do not respond to reasonable requestsfor information at all, leaving investors few options forrecourse. Filing shareholder proposals is one strategy used byinvestors to encourage companies to report on various risks notcaptured fully by existing disclosure requirements, but ruleslimiting the topic and scope of these proposals effectivelypreclude investors from obtaining comprehensive humancapital-related information in this way. For example, ashareholder may request information about human rights risksin the supply chain but proposals addressing other humancapital matters, such wages and benefits, are barred, with fewexceptions, by the “ordinary business” exclusion in theshareholder proposal rule. 44 Recent efforts to place tighterrestrictions on shareholder proposals, such as legislation thatwould dramatically increase the ownership threshold investorsmust meet to file a proposal, may effectively eliminate thisstrategy. 45Data acquired by searching websites have similarshortcomings. Some investors have turned to online socialmedia sources such as Glassdoor, a jobs and recruiting sitewith a database of millions of employee reviews of companiesas well as salary information. 46 Reviewers can describe prosand cons of a company, indicate whether they approve of itsCEO and critique their employee benefits. Users can alsoprovide information about interviews at companies. Glassdoordata thus have the potential to shed light on companies’human capital management. Glassdoor reviews areanonymous, though, and thus vulnerable to manipulation bycompanies seeking to project a positive image. Even assumingall reviews are penned by actual current or former employees,Glassdoor is subject to the same bias as other review sites:E.g., Best Buy Co., Inc. (Mar. 8, 2016) (allowing exclusion on ordinarybusiness grounds of proposal regarding minimum wage, r

The Human Capital Management Coalition (the "HCM Coalition") respectfully submits this petition for rulemaking pursuant to Rule 192(a) of the Commission's Rules of Practice. 1 As representatives of the HCM Coalition, a group of institutional inves tors with 2.8 trillion in assets, we request