Transcription

Ka Pili KaiUniversity of Hawaiÿi Sea Grant College Program Vol. 36, No. 3 Fall 2014Coastal Hazards, Climate Change,and Community Resilience

University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College ProgramKa Pili KaiContentsVol. 36 No. 33Preparing for Natural Hazards6Maui Looks Toward the Future: Rebuilding Safer,Stronger, Smarter!8Communicating a Great Aleutian Tsunami and theO‘ahu Coastal Communities Evacuation PlanningProject10Risk and Vulnerability Assessment of Sea-Level Rise andCoastal Hazards12UH Sea Grant Helps Kaua‘i County Prepare for ClimateChange14Coral Divers Mainstream Shoreline Protection withDredge Site Mitigation in the MarshallsIn this issue.We have all heard the dire warnings coming at us from all directions – climatechange is one of the most important issues facing mankind, and could bringdrought, sea-level rise, coastal erosion, flooding, increased coastal storms, risingtemperatures, ocean acidification, and other devastating impacts in the comingyears. While it is easy to become discouraged and feel like there is nothing thatwe as individuals can do, the dedicated staff and faculty at the University ofHawai‘i Sea Grant College Program (UH Sea Grant) are tackling these complexissues head-on, and working closely with our partners and policymakers toensure the communities we serve are adequately prepared for whatever the futurebrings. In this issue you will read about how UH Sea Grant’s unique research andoutreach capabilities are assisting coastal communities become more resilient,how we are assisting residents and decision-makers become more aware of theimplications of climate change, and, importantly, have a greater understanding ofwhat changes need to occur today to be prepared for tomorrow.Cindy KnapmanCommunications Leader2 Ka Pili KaiKa Pili Kai (ISSN 1550-641X) is publishedquarterly by the University of Hawaiÿi SeaGrant College Program (UH Sea Grant), Schoolof Ocean and Earth Science and Technology(SOEST). UH Sea Grant is a unique partnershipof university, government, and industry,focusing on marine research, education andadvisory/extension services.University of Hawai‘iSea Grant College Program2525 Correa Road, HIG 208Honolulu, HI 96822Director:E. Gordon Grau, PhDCommunications Leader:Cindy KnapmanMultimedia Specialist:Heather DudockPeriodicals postage paid at Honolulu, HIPostmaster: Send address changes to:Ka Pili Kai, 2525 Correa Road, HIG 208Honolulu, HI 96822(808) 956-7410; fax: (808) awaii.eduThe University of Hawaiÿi was designated a SeaGrant College in 1972, following the NationalSea Grant College and Program Act of 1966.Ka Pili Kai is funded by a grant fromthe National Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration, project C/CC-1, sponsored bythe University of Hawaiÿi Sea Grant CollegeProgram/SOEST, under Institutional Grant No.NA05OAR4170060 from the NOAA Officeof Sea Grant, Department of Commerce. Theviews expressed herein are those of the authorsonly.UNIHI-SEAGRANT-NP-14-03Ka Pili Kai Editor: Cindy KnapmanLayout and Design: Heather DudockContributing Writer: Keano PavloskyOn the cover: Coastal erosionthreatened homes along SunsetBeach, North Shore, O‘ahu inOctober 2013. Photo: BradleyRomine

Preparing for Natural HazardsBy Dennis Hwang, UH Sea GrantCoastal Hazard Mitigation SpecialistFThe third edition of theHawai‘i Homeowner’sHandbook to Prepare forNatural Hazards is availablenow. For more informationvisit: irst published in 2007 by the University ofHawai‘i Sea Grant College Program (UHSea Grant), the Homeowner’s Handbook toPrepare for Natural Hazards is a guide to the scienceand risk of regional natural hazards that may affecthomeowners—for example, hazards relevant toHawai‘i homeowners include hurricanes, tsunami,floods, and earthquakes. Over 65,000 copies havebeen printed and distributed to date, and the earliereditions discuss traditional emergency preparationitems such as emergency supplies, evacuation plansand evacuation kits, as well as non-traditional items,such as methods for strengthening a home to betterwithstand hazard events. Addressing non-traditionalpreparations was viewed as critical because the houseis the major investment for many families, and alsoprovides protection from the elements. Moreover, ifthe house is sufficiently strong, either in its originaldesign or through retrofit, it may be possible to shelterin place during a hurricane. This is a big concern sincethere is only shelter space for roughly 35 percent ofHawai‘i’s population in public hurricane shelters.Multiple major and minor updates to the Hawai‘iHomeowner’s Handbook to Prepare for NaturalAbove: Hurricanes Iselle and Juliothreatened Hawai‘i in August 2014. Iselleweakened to a tropical storm beforestriking Puna in Hawai‘i County. Therewas considerable wind damage to roofsand many fallen trees, as well as wavedamage to coastal homes. Fortunately,Julio, which weakened only slightly,veered to the east. These systems are areminder of Hawai‘i’s vulnerability totropical storms and hurricanes.3 Ka Pili Kai

Hazards have been made between publication of thefirst edition and of the current (third) edition. Somehighlights from previous editions include:First Edition: Hurricane clips, and over 12 ways toprotect windows. Window protection is essential tocreate a wind and rain resistant envelope around thehouse during a hurricane—masking tape will notwork.Second Edition: More in-depth information onhurricane clips, specifically, the Hawai‘i PlantationTie (HPT) developed just for Hawai‘i. With the HPTclip and the H3 clip, the majority of single-wallhouses in the state can now be retrofitted so thatthe roof is better able to stay on the house during ahurricane. When Hurricane Iniki hit Kaua‘i, there wasa total of over 7,000 houses damaged or destroyed,with many homes having lost their roofs due to a lack of hurricane clips. Since O‘ahu has eight times thenumber of structures as Kaua‘i, a ballpark estimate of over 50,000 damaged structures resulting from a similarevent on O‘ahu is possible; this figure has been confirmed by a Federal Emergency Management Agency(FEMA) risk assessment. The second edition also addressed post and pier retrofits (i.e., houses on “tofublocks”), which are of benefit during a hurricane or an earthquake so that the house stays on its foundation.Such modification is especially important for those on Maui and Hawai‘i Island, where there is a greaterearthquake risk.The third edition of the handbook is currently online and will be printed in the fall of 2014 with four newappendices. The appendices address a variety of new topics, such as:Storm Panel Screws: These screws, made by Simpson Strong-Tie, provide a quick way to attach plywoodor plastic honeycomb panels to windows (Appendix C).Asphalt Shingle Roofs and Ridge Vents: This section includes graphical guidance and instructions on howto install a stronger asphalt shingle roof and ridge vent, based on existing FEMA documents (Appendix D).Solar Photovoltaic Panels: While it is not possible to prevent solar panel damage during a high wind event,the key is to insure the system and make sure it is properly attached to the rafters so they do not blow offduring a hurricane (Appendix E).Working with the Community: If individuals and families are properly prepared, they are better ableto help the community during a hazard event. Information on numerous volunteer organizations andprograms is provided including those for the American Red Cross, Citizens Emergency Response Teams(CERT), and Hawai‘i Hazards and Resiliency Program (HHARP) (Appendix F).Appendices E and F are expected to be particularly useful going forward. In the year 2013 alone, over 17,500solar units were installed statewide, and many of the houses were reroofed beforehand. These modificationsprovide opportunities for the homeowners to use information in the handbook to strengthen roofs and toensure the solar panels will not fly off during a hurricane.Finally, the third edition includes updated sections that provide information related to lessons learned fromthe Hurricane/Tropical Storm Iselle event. Although many people were prepared, many were not. Thehomeowner’s handbook reinforces the idea of being prepared before a watch or warning is issued—thegoal is to avoid needing to go to the store at that time for water, food, gasoline, or supplies. Additionally, inspite of the fact that Iselle hit Hawai‘i County only as a tropical storm and not a hurricane, considerable treedamage occurred, which is also covered in the handbook, as well as roof damage (especially related to the newAppendix D).4 Ka Pili Kai

We attribute the success of the homeowner’s handbooks to three reasons.First, it has an easy to understand graphical format, which is moreapproachable for homeowners who may not have a science background.Second, it contains only the information that is most relevant to thelocal community. Third, and most importantly, it builds upon strongpartnerships with other government agencies, volunteer organizations,and companies that provide technical advice, outreach support, andfunding for the different print runs. Some interesting aspects ofhomeowner’s handbook partners and the roles they play are:There are 28 key partners who assisted in the development of thehomeowner’s handbook, and many of which have been involved since2007.One new partner, West Oahu Roofing, is featuring the new guidancefor the installation of stronger asphalt shingle roofs on its website(Appendix D), and has written articles in the Sunday paper on theproper methods.The FEMA Building Science Branch will be contributing fundingto print the third edition. Information in Appendices D (roofing) andE (solar photovoltaic panels) may be used to update or create newguidance documents in its division.Although many people were prepared, othersrushed to the stores for emergency supplies.A key goal in the homeowners handbook isto avoid having to go to the store during ahurricane watch or warning for emergencysupplies. They should already be in placebefore the hurricane season begins.Among our long-time partners, Zephyr Insurance holds annual workshops for hundreds of its agents onhurricane science and the home retrofits outlined in the handbook. State Farm provides annual financialsupport for printing and has new social media initiatives to encourage preparation. Simpson Strong Tieholds an annual workshop for builders and inspectors that cover retrofits in the handbook.Key long time partners also include the National Weather Service, the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center,and the State Flood Insurance Program at the State of Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resourceswho have contributed maps, figures, and suggestions that have been incorporated in the handbook.Many of the partners for the Hawai‘i handbook have extended this collaboration to other states includingSimpson Strong-Tie, American Red Cross, FEMA, and the Coastal Zone Management Program.Based on the enormous amount of interest in the homeowner’s handbook developed for Hawai‘i, Sea Grantprograms in many other areas of the country expressed an interest in developing their own state-specificversions. Currently, modified versions of the homeowner’s handbook are available in Mississippi, Alabama,Louisiana, Texas, Florida, Delaware, and Massachusetts. The book is also in the early stages of preparation forNew Jersey, Washington, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Interest has been expressed for handbooksin the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of the Philippines, especiallyafter Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda.Some interesting facts about these regional handbooks include: Texas handbook is offered in English and Spanish Marshall Islands handbook will be in English and Marshallese Delaware handbook has a climate change component, and discusses Hurricane Sandy Louisiana handbook is in its second edition, and draws support from many key partners, including FEMA Massachusetts handbook has been very popular—during the 2013 hurricane season, the local Sea Grantoffices ran out of 5,000 copies by August. A new print run of 10,000 copies will be finalized by the endof 2014All homeowner’s handbooks are available as free PDF files online. Readers can obtain the PDF by conductingan internet search for: “Homeowner’s Handbook to Prepare for Natural Hazards,” and including the name ofthe state of interest. Thank you to UH Sea Grant Communications for sharing the homeowner’s handbooktemplate with other states.5 Ka Pili Kai

Maui Looks Toward the Future:Rebuilding Safer, Stronger, Smarter!By Tara Owens, UH Sea Grant Coastal Processes Extension AgentAresident of Hana, a relatively isolated townon Maui’s east side, recently recounted at acommunity workshop just how taxing andtime-consuming it was to get permits to rebuild herfamily’s home after a destructive fire. In this case,the permitting process alone delayed rebuildingby nearly 10 months. While Hana town itself isisolated, the situation of delayed rebuilding, it turnsout, is not an isolated experience. Similar storieshave been shared by other Maui residents fromaround the island. For this Hana resident, a followon question emerged: “What will the county dowhen there are hundreds of houses to rebuild after adisaster? Surely it won’t take 10 months just to getpermits when we need to get our families back intheir homes?”These types of permitting delays are one ofmany challenges that Jim Buika, a coastal zonemanagement planner for the County of Maui andTara Owens, a UH Sea Grant coastal hazardsextension agent, are addressing by guidinga planning process to develop post-disasterreconstruction guidelines and protocols for theCounty of Maui. In a coastal community, it’s not IFbut WHEN the next coastal storm will hit. Hurricane6 Ka Pili KaiIniki in 1992 caused extensive damage on Kaua‘i,and Hurricane Iselle this past August was a recentreminder of the need to prepare. So, this planningprocess has initially involved understanding anddocumenting delays to early reconstruction basedon experiences from previous damaging events. Theresulting guidelines and protocols will seek to reducedelays and enable the county to offer immediatedirection and pre-determined steps to residents torepair or rebuild damaged property. A grant from theNOAA Sea Grant Coastal Storms Program for thePacific Islands Region has provided the opportunityfor the county to take on this critical task.Buika and Owens, along with a locally-basedconsultant team, are working with County of Mauistaff and Maui communities, including the islandsof Moloka‘i and Läna‘i, to understand their specificneeds and priorities for rebuilding when the timecomes. The overarching goal of this effort will be to“rebuild safer, stronger, and smarter” in a plannedand efficient manner, especially in sensitive shorelineareas. This planning process aligns nationally withother federal initiatives to encourage communitybased recovery planning, including FEMA’s NationalDisaster Recovery Framework.

Previous page left: Shoreline armoring, Maui. Previous page right: Community workshop participants, Hana, Maui.Planning for rebuilding is new territory in Hawai‘i,and there is no prescription for how it should bedone, and it can sound a lot easier than it actuallyis. The team has learned that making locallyspecific guidelines involves difficult decisions anduncovers some significant resource (human andphysical) challenges. For example, if damages areregional or island wide, how does the county triagereconstruction? Would a roof replacement garnerthe same attention and permitting requirements as ahome that needs to be mostly rebuilt? This projectaims to provide guidance to reduce the deliberationfor these kinds of decisions. When will inspections benecessary, especially if inspectors are in short supply?This project expects to propose solutions for criticalresource gaps.But permitting decisions are only part of thechallenge. When the time comes, the County of Mauiintends to make sure that environmental and culturalresources are protected in the rebuilding process. Toincorporate environmental considerations into theprocess, the project team has devised a “DecisionMatrix” that factors in a range of shoreline typesof varying sensitivities (examples: pristine sandybeach versus armored coastline) in juxtapositionwith damage impact scenarios (examples: roofreplacement versus total rebuild). The intent is tocarefully balance consideration for both the naturaland built environments. For example, how will thecounty respond when beaches are severely erodedby storm waves and homeowners request shorelinearmoring? This scenario isn’t uncommon already–thehomes on Sunset Beach, O‘ahu were threatened bysevere erosion just last winter–and history has shownthat the armoring approach has resulted in winnersand losers by protecting private land at the expense ofthe beach. These scenarios will be addressed by theproject, and alternative adaptation strategies will beemphasized.The “Decision Matrix” has evolved into a gameboard of sorts, as a tool to collect information fromthe community about their concerns and priorities.The feedback has been surprising in some cases,so this method of interactivity has turned out to bevery insightful. As the project team wrapped up arecent community workshop, a few comments fromparticipants highlighted the challenges with, andthe critical need for, this planning process. Afterthinking through some of the scenarios and decisions,one resident stated, “Well, I think everybody inthis room now understands how difficult your jobsreally are.” Another resident thanked the staff for“being ahead of the curve for all of us.” As a resultof these community workshops, and years of coastalmanagement experience on Maui, the first “MauiCounty Post-Disaster Guidelines and Protocols” willbe drafted by this winter.Below: Homes on the north shore of O‘ahu were threatened by severe erosion in the winter of 2013. Dolan Eversole7 Ka Pili Kai

Communicating a Great Aleutian Tsunamiand the O’ahu Coastal Communities Evacuation Planning ProjectBy Matthew Gonser, AICP, UH Sea Grant Community Planning and Design Extension AgentThe magnitude 9.0 earthquake in Tohoku, Japan onMarch 11, 2011, resulted in one of the largest tsunamisin recorded history. The earthquake and subsequenttsunami was a very low probability, but extremely high impactcatastrophe. Since this event there has been great interest inthe geophysical research community to better understandpotential sources of large tsunamis.The Hawaiian Islands have been subjected to large tsunamisin 1946, 1952, 1957, 1960, 1964, and 2011. The largesttsunamis in Hawai‘i were from the 1946 and 1957 magnitude8.6 earthquakes, which were focused east and west of the EastAleutian Islands, respectively. The region between these areasis focused directly at the Hawaiian Islands; tsunamis fromgreat earthquakes located here pose the most significant threatto Hawai‘i.It has become increasingly recognized that past inundationmodeling for Hawai‘i tsunami evacuations did not considerall possible sources of tsunamis. Existing evacuation zonesin Hawai‘i heretofore were based just on re-created historicaltsunami events within the past 100 years, i.e., 1946 (WestAleutian), 1962 (Kamchatka), 1957 (East Aleutian), 1960(Southern Chile), and 1964 (Alaska). The past 100 years doesnot comprise all possible credible hazard threats. It is morelikely that future subduction earthquakes will be different inlocation and magnitude and not identical to the past.8 Ka Pili KaiThis recognition has led to an analysis of the potential forother sources of large tsunamis that could affect Hawai‘i inexcess of the historical record. The first geophysical analysisof such scenarios was carried out by seismologist Dr. RhettButler of the University of Hawai‘i at Mänoa under contractwith the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency (formerlyState Civil Defense). This research included a detailed,systematic analysis of sources of great earthquakes along theAleutian-Alaskan Arc megathrust subduction zone capableof producing large tsunamis. Characteristics of prior great(magnitude 9.0 ) earthquakes in the Pacific Rim were alsoused as the basis for earthquake fault displacement models,which were reviewed and vetted by a U.S. GeologicalSurvey (USGS) team. Two independent tsunami simulationmodels (NOAA-SIFT or short-term Inundation Forecastingfor Tsunamis and the UH NEOWAVE or Non-hydrostaticEvolution of Ocean WAVE) were used to estimate tsunamiinundation in the Hawaiian Islands from this tsunamigenicregion. The focus of this research effort was to estimate thelargest tsunami that may impact the state of Hawai‘i fromdistant, great Aleutian magnitude 9 earthquakes.The research suggests:Great earthquakes along the eastern Aleutian arc pose acredible worst case tsunami threat to Hawai‘i due to theirproximity (short, 4.5 hour travel time), historical impact (the

Left: Inundation from the 1946 tsunami in Hilo reached several thousand feet inland. This photo depicts the tremendous power of a tsunami.Taken from the Hilo Tribune-Herald. Photo courtesy of Pacific Tsunami Museum–Andrew Spaulding Collection.largest historical tsunamis have originated in the Aleutians),and directional focus of tsunami energy toward the HawaiianIslands.The eastern Aleutian region is capable of a giant magnitude9 earthquake along a section of the Aleutian island arcdirectly facing Hawai‘i.Magnitude 9 earthquakes in the Aleutians can producetsunamis in Hawai‘i that substantially exceed currenttsunami evacuation maps.Through the O‘ahu Coastal Communities Evacuation Planning(OCCEP) project (funded by the City and County of HonoluluDepartment of Emergency Management (DEM) and the O‘ahuMetropolitan Planning Organization (OMPO), UH Sea Grantis communicating these research findings of a Great AleutianTsunami (GAT) scenario and the resultant Extended TsunamiEvacuation Zone (ETEZ) on O‘ahu. The project is ongoingand project partners have identified several potential concernsin communicating the GAT and ETEZ:1. Though an extraordinary event, there is a need to developa secondary evacuation zone for a GAT event due to theinundation depth and extent, and the potential for great lossof life that would result from a GAT scenario if only thepresent evacuation zone is used.2. Confusion (and either panic or disbelief) during evacuationif the public is not well informed on what to do and whereto go in the event of a GAT evacuation warning.3. The public may be confused by an evacuation mapdepicting an ETEZ without dedicated and widespreadBelow left: Map depicting those large tsunamis that have impactedthe Hawaiian Islands over the past 100 years, with their locationsand approximate travel times.outreach and education of the reasons for new (2014)evacuation maps relatively soon after the last map updateof 2010.4. Currently, there is no distinction for the magnitude ofextraordinary events like the GAT scenarios. At presentthere is a single run-up threshold value of one meter thatis used to trigger tsunami evacuation statewide. However,the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) is in theprocess of developing a warning criteria procedure forGAT events.5. Given that Hawai‘i tsunami warnings have overestimatedrun-ups from events over the past 25 years, there may bedeveloping complacency with any warnings regardless ofthe event.6. Specific evacuation refuge and route planning has notyet been conducted for the Honolulu urban area includingWaikïkï, which adds opportunity and complexity whenconsidering vertical evacuation (i.e., moving to higherfloors in tall buildings).7. Though the annual probability of a GAT event is verylow, potential impacts are severe requiring clearmessaging and continued preparedness measures.In response to many of these concerns, the OCCEP iscompleting updated refuge and route information to berefined through participatory community workshops.Additionally, coordinated messaging on the reasons forpreparing this operational contingency plan is beingdiscussed by the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency,the four county civil defense agencies, and the PTWC.Below right: Numerical simulation of the 1946 Aleutian tsunamiwaves propagating through the Hawaiian Islands (5 hours afterthe earthquake). Image courtesy E. Gica9 Ka Pili Kai

Risk and Vulnerability Assessmentof Sea-Level Rise and Coastal HazardsBy Dolan Eversole, NOAA Sea Grant Coastal Storms Program Coordinator, Pacific Islands RegionIn the last ten years, the Gulf region and Eastern seaboard of the U.S. have experienced repeatedsevere impacts from hurricane inundation including Hurricane Katrina and Rita in 2005,Hurricane Ike in 2008, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Much of the devastation was caused bystorm surge which exceeded 17 feet in parts of Texas during Ike, and over 27 feet in Mississippiduring Katrina. While Hawai‘i did not experience any of the impacts from these hurricanes,the questions arose, what impact would a local hurricane and the resulting storm surge have onHonolulu’s coastline? What will happen to critical infrastructure when an event such as a hurricaneor tsunami occurs in areas already experiencing sea-level rise inundation? Since recent globalprojections anticipate a rise in sea level of one meter or higher by the end of the century, thesequestions are of critical importance.In response, the NOAA Sea Grant Coastal Storms Program in the Pacific Islands Region funded aUniversity of Hawai‘i study to assess the risk and vulnerability of urban Honolulu, Hawai‘i. The areachosen for the study stretches between Diamond Head and Pearl Harbor and includes high densitydevelopment, a large population, major critical infrastructure, and is also at low elevation so it is athigh risk. Importantly, the area is also responsible for generating over 43 billion dollars in economicactivity annually, and is a major tourism hub for the state.The questions surrounding climate change and sea-level rise adaptation have brought a lot of focuson what hazard mitigation plans are currently in place. While this study is not a hazard mitigationplan in itself, it generates the data that would be used, and the results from this project are helping toinform successful adaptation and hazard mitigation planning. This is especially relevant as the statedevelops comprehensive climate change and sea-level rise adaptation strategies. Through targetedoutreach to local emergency and resource managers, decision-makers, and affected communities, theapproach taken in this project can serve as a roadmap for assessing the impacts of sea-level rise andcoastal hazards in other parts of the state.10 Ka Pili Kai

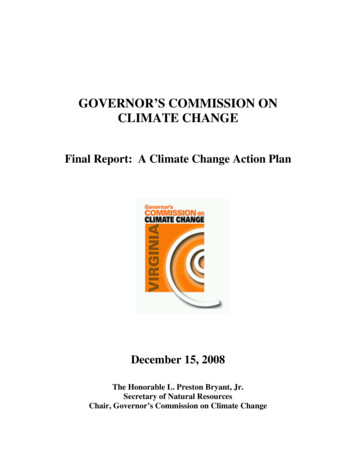

Assessment of Honolulu’s urban corridor.Model results show a significant effect oncoastal hazard inundation as a result ofsea-level rise (SLR). Increased sea level isshown to greatly increase both the extentand depth of inundation along the coast.Data produced by: Dr. Charles “Chip”Fletcher and Dr. Kwok Fai Cheung. Mapsproduced by Matthew Gonser.Left: Shaded gray areas indicate inundationat one meter of SLR within Honolulu.In an effort to communicate theresults of this project, an onlinemapping tool has been developed toserve as a decision-support tool forlocal planners and decision-makers.This online resource is availablethrough the Pacific Islands OceanObserving System website: http://oos.soest.hawaii.edu/pacioos/projects/slr/. In addition, the National Oceanicand Atmospheric Administration hasproduced a suite of sea-level riseinundation maps for Hawai‘i and thePacific which are also available onlineat http://coast.noaa.gov/slr.This project demonstrates thatsea-level rise will significantlyincrease the impacts of coastalhazards in Honolulu’s urban corridor,the most populated and economicallyactive area in the state of Hawai‘i.The analysis indicates that 80 percentof the area’s economy, nearly halfof the population, and much of theinfrastructure and land are at riskof inundation. It is clear then thatthere is a need to develop long-term,risk-based strategies for hazardmitigation, as well as adaptation ofsystems to reduce the potential forharm. The results of this project canhelp inform successful adaptation andhazard mitigation planning and themethods and techniques employedin this project can be translated toother coastal communities in Hawai‘iand the Pacific Islands region, as anexample.Shaded gray areas indicate potential inundation from a hurricane in addition to1 meter of SLR within Honolulu. Light to dark gray indicates inundation levels0.5 to 2.0 meters.Shaded gray areas indicate potential inundation from a tsunami in addition to 1meter of SLR within Honolulu. Light to dark gray indicates inundation levels 0.5to 2.0 meters.Shaded gray areas show an overlay of the three modeled inundation scenarios(from light to dark): hurricane, tsunami, and 1 meter of SLR within Honolulu.11 Ka Pili Kai

UH Sea Grant Helps Kaua’i CountyPrepare for Climate ChangeBy Ruby Pap, UH Sea Grant Coastal Land Use Extension AgentThe island of Kaua‘i, the oldest of the mainHawaiian islands at approximately six millionyears old, is one of the most remote islandsin the world. This remoteness, coupled with theislands’ increasing vulnerability to coastal hazardsdue to climate change and sea-level rise, promptedthe Kaua‘i County Planning Department to take avisionary step in its efforts to help the communityprepare.The Kaua‘i coastline is susceptible to a variety ofnatural hazards, including coastal storms, high waveevents, flooding, coastal erosion, and tsunamis. Allof these hazards threaten lives, property, the naturalenvironment, and, ultimately, economies. Increasingdevelopment in coastal areas not only places morepeople and property at risk to coastal hazards, butit can also degrade the natural environment andi

Grant College in 1972, following the National Sea Grant College and Program Act of 1966. Ka Pili Kai is funded by a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, project C/CC-1, sponsored by the University of Hawaiÿi Sea Grant College Program/SOEST, under Institutional Grant No. NA05OAR4170060 from the NOAA Office