Transcription

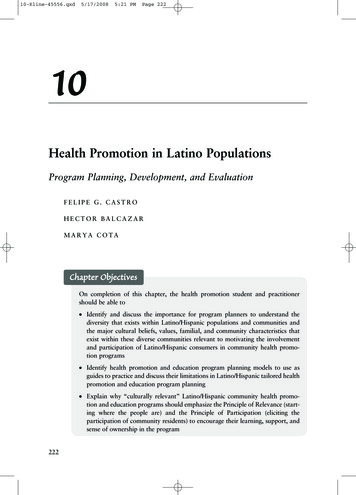

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 22210Health Promotion in Latino PopulationsProgram Planning, Development, and EvaluationFELIPE G. CASTROHECTOR BALCAZARMARYA COTAChapter ObjectivesOn completion of this chapter, the health promotion student and practitionershould be able to Identify and discuss the importance for program planners to understand thediversity that exists within Latino/Hispanic populations and communities andthe major cultural beliefs, values, familial, and community characteristics thatexist within these diverse communities relevant to motivating the involvementand participation of Latino/Hispanic consumers in community health promotion programs Identify health promotion and education program planning models to use asguides to practice and discuss their limitations in Latino/Hispanic tailored healthpromotion and education program planning Explain why “culturally relevant” Latino/Hispanic community health promotion and education programs should emphasize the Principle of Relevance (starting where the people are) and the Principle of Participation (eliciting theparticipation of community residents) to encourage their learning, support, andsense of ownership in the program222

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 223Health Promotion in Latino Populations223 Formulate a conceptual framework for planning health promotion and education programs within several different Latino/Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Mexican,Guatemalan, Puerto Rican, Cuban) that offer health information, motivateshealthy behavior change, and promotes such change in a culturally relevantmanner using interventions that build on the existing cultural strengths of eachsubgroup Identify and differentiate between program goals and program objectives andidentify evaluation methods for assessing those program goals and objectives Explain the importance and usefulness of assessing “acculturative status” amongLatinos/Hispanics in the initial assessment of health needs Differentiate between and describe at least the three following aspects of program implementation as it encourages an effective Latino/Hispanic-based healthpromotion program:1. Client preparation by advising them on guidelines for their active participation2. Enhancing the cultural competence of program staff3. Enhancing the cultural competence of the program’s administrative staffand infrastructureINTRODUCTIONA Latino Perspective on Health PromotionThis chapter presents a Hispanic/Latino1perspective on the design of effective and culturally relevant health promotion programs.Generally, the process of program designinvolves four basic steps: Step 1—ProgramPlanning, Step 2—Program Development, Step3—Program Implementation, and Step 4—Program Evaluation (McKenzie, Nieger, &Smeltzer, 2005). This stepwise approach isoutlined further within a “User-FriendlyWorksheet for Developing Health PromotionPrograms”2 (see Appendix A). The observations presented in this chapter include insightsgained by the authors in their many years ofresearch and program development within thefield of health promotion. A major aim of thischapter is to provide scholarly and practicalinformation for helping health professionalsdesign and work with health promotionprograms that serve Latino populations, inefforts to reduce or eliminate health disparities(Carter-Pokras & Baquet, 2002; NationalAlliance for Hispanic Health, 2001; U.S.Department of Health and Human Services[DHHS], 2000). This perspective recognizesthat enacting healthy behavior change is noteasy. It requires the acceptance of the need forchange, motivation, and commitment to thischange, as well as guided and sustained effort.These setting conditions for healthy behaviorchange are typically more difficult for manyLatino and other racial/ethnic minoritypersons, especially when they reside withinlow-income neighborhoods or within unstablefamilial or other high stress living situations.Cultural Enhancement of Program and Staff.In a quest to improve health promotion program effectiveness and staff capacity, culturally enhanced health promotion programscan be referred to as being culturally relevant

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 224224(designed for relevance) or culturally responsive (designed for responsiveness) to the cultural needs of members of a targeted or specialpopulation. In contrast, health educators,health providers, or other program staff can bedescribed as being culturally sensitive, culturally competent, or even culturally proficient, intheir cultural capacity to understand, appreciate and actively engage members of a targetedor special population. The hallmark of cultural capacity among program staff requirestheir abiding respect for diversity and for thewell-being of members of a special population(Sue & Sue, 1999). Cultural capacity is thentranslated into culturally responsive serviceswhen program staff deliver culturally relevantservices or program activities. In addition,enhancing the cultural capacity of programstaff involves increasing their clinical skills forbeing more responsive to diverse participantor patient needs. Thus, respect for diversityand community collaborations are key elements of culturally responsive health servicesand programs. The ultimate goal is to increasepatient treatment adherence, satisfaction, andpositive health outcomes.Devoid of programmatic attention to cultural issues, many mainstream health promotion programs have exhibited limited successin attracting, involving and retaining Latinoconsumers/clients3 (Hirachi, Catalano, &Hawkins, 1997; Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith, &Bellamy, 2002). Motivating Latino consumerinvolvement and participation in a health promotion program remains a major challenge.Nonetheless, this challenge can be met if program planners appreciate the cultural diversitythat exists within a Latino community byunderstanding its prevailing cultural beliefs,values, and cultural norms, while also understanding the within-group variability on thesecharacteristics that also exists among membersof that community (Castro et al., 2006).Characteristics of Health Promotion Programs.Initiating and sustaining health change effortsHISPANIC/LATINO POPULATIONSto reduce health disparities involves programmatic interventions that mobilize personal,interpersonal, and environmental resources ina unified and integrated manner. A welldesigned and culturally responsive health promotion program helps sustain these effortsacross time to produce genuine health-relatedchanges and improvements in health. Healthpromotion programs typically focus onhealthy change to reduce risks or the severityof one or more of the lifestyle disorders: cardiovascular disease (reducing elevated lipids,reducing high blood pressure), the cancers(screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, orother cancers), diabetes mellitus (promotingweight reduction, management of bloodglucose levels), arthritis and other musculoskeletal diseases (Brownson, Remington, &Davis, 1998), as well as reducing the diseaseburden of addictive disorders (alcohol abuse,tobacco use, use of illegal drugs, excessivefood consumption, other addictions). Ingeneral, one goal of health promotion programs is to reduce health disparities on oneor more of the 10 leading health indicators:physical inactivity, overweight and obesity,tobacco use, substance use, responsible sexualbehavior, mental health, injury and violence,environmental quality, immunization, andaccess to health care (U.S. DHHS, 2000).Thus, a health promotion program consists of a multisession program of organized activities designed to promote healthylifestyle changes. A well-designed health promotion program will typically include severalcomponents: (1) informational knowledge toprovide health information and to changemaladaptive beliefs about health, (2) motivational messages to prepare the participant forbehavior change efforts, (3) skills development via techniques that build capacity forchange, (4) social supports that elicit the aidof significant others, and (5) environmentalchanges to reduce barriers to change and tomobilize resources for making health-relatedchanges.

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 225Health Promotion in Latino PopulationsInfusing Cultural ResponsivenessInto Program DesignThe Principles of Relevance and of Participation.Culturally relevant community-based programs should be designed according to twoimportant systems principles: (1) the principleof relevance, “starting where the people are”and (2) the principle of participation, elicitingthe participation of community residents, thuspromoting their “sense of ownership” in theprogram, while also fostering “active learning”through participation (Minkler, 1990). The useof this approach operates as a communitygrounded needs assessment to identify andrespond actively to the most pressing healthneeds within a local community. Accordingly,from the perspective of the participatorysocial action research approach (Minkler &Wallerstein, 2003), community residents areinvited to participate in the conceptualizationand design of a health promotion program.Under the principle of participation, programdevelopers elicit the views of community leaders, stakeholders, and residents regarding thenature and extent of important communityhealth needs. This approach establishes ahealth partnership, while also challenginghealth professionals to apply their social, psychological, and medical knowledge towardaddressing the community’s expressed needs(Rawson, Martinelli-Casey, & Ling, 2002). Insummary, this health partnership “grounds”the health promotion program within the contemporary health needs and desires of localcommunity residents.A Principle of Cultural Relevance. An emerging principle for health promotion may beidentified as the principle of cultural relevance.A health promotion program that is designedto effectively reduce or eliminate health disparities within a specific minority populationrequires that the health planner be deeplyknowledgeable of the culture of the targetedgroup, while also having respect for members225of that group, and consulting with members ofthat group to more fully understand thegroup’s cultural diversity and complexity in itsvalues, major beliefs, customs, and traditions(Orlandi, Weston, & Epstein, 1992). In thisregard, health promotion programs can contribute significantly toward reducing healthdisparities in Latino populations in severalways. These include the following: (1) facilitating consumer access to program activities inSpanish, as needed; (2) employing bilingual/bicultural staff and training them to becomeculturally competent; (3) integrating Latinocultural factors into core program components(family-oriented values, i.e., familism, personalismo, respeto, simpatia) (Castro & HernandezAlarcon, 2002; Marin & Marin, 1991);(4) adjusting program activities in accord withlevels of acculturation, as these exist amongprogram consumers; and (5) developing sensitivity to features of the local Latino communityand its culture. A health promotion programcan “work” when it offers health information,motivates and sustains healthy behaviorchange, and promotes this change in a culturally relevant manner using intervention activities that build on existing cultural strengths.The design of such interventions should also beguided by empirically based health promotionresearch that informs program developers andstaff about empirically validated interventions“that work” in changing mediators of healthybehavior change (Kellam & Langevin, 2003;MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, &Sheets, 2002).STEP 1: PROGRAM PLANNINGContrasting Roles of Theory,Models, and Grassroots ApproachesContrasting Approaches to Health PromotionProgram Planning. In the field of preventionscience, a dynamic tension exists regardingcompeting approaches toward preventionprogram planning. Generally, the “academic

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 226226approach” emphasizes a theory- or modeldriven “top-down” strategy that consists of anorganized plan for program design. In contrast,the “grassroots community approach” builds aprogram from the “bottom-up,” based on sensitivity and responsiveness to current community needs. The strength of the “academicapproach” involves its focused organizationand planning; its weakness lies in a possiblelack of fit with contemporary communityneeds and preferences, while its emphasis onfidelity in program delivery may introduceinflexibility to changing community needs. Incontrast, the strength of the grassroots community approach lies in its closeness and sensitivity to local community needs and a sensitivityto the community culture; its weakness lies in autilization of activities or interventions thatmay not be empirically validated and may beineffective in producing healthy behaviorchange on targeted behaviors or on otherimportant health outcomes (Schinke, Brounstein,& Gardner, 2002).Importance of Theory to Guide ProgramDesign. In the applied setting, many social service and health interventions are deliveredbased on units of service to address a specificpresenting problem. Unfortunately, such interventions are seldom governed by a well-specifiedtheoretical, conceptual, or logic model; theyoften focus concretely on service delivery withlimited efforts to address the underlying“causal” disease mechanisms that this intervention purports to change. In contrast, thecontemporary academic approach to healthpromotion program planning is based on several health promotion theories and models.Among these models, the most popular arethe Health Belief Model (Becker, 1974;Hochbaum, 1958; Rosenstock, 1990), theTheory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen &Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein, 1967), the Theory ofPlanned Behavior (Ajzen & Madden, 1986),Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1986;Perry, Baranowski, & Parcel, 1990), Green’sHISPANIC/LATINO POPULATIONSPRECEDE model (Green, Kreuter, Deeds, &Partridge, 1980), and Diffusion of Innovation(Orlandi, Landers, Weston, & Haley, 1990;Rogers, 1983), the Stages of Change Model(the Transtheoretical Model) (Prochaska& DiClemente, 1992), Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991), and theEcodevelopmental Model (Szapocznik &Coatsworth, 1999). Details of these theoriesand models as applied to health promotionhave been described in detail by others(DiClemente, Crosby, & Kegler, 2002; Glanz,Rimer, & Lewis, 2002).These classical theories and models of healthand behavior offer important tools to guidehealth promotion program design, becausethey summarize the cumulative scientificknowledge gained from epidemiology, prevention science, health promotion, and other academic fields, as it describes and explains “whatworks” and “how it may work,” by “mappingout” processes that govern healthy behaviorchange. Understanding the major factors thatinfluence healthy behavior change, as describedby these theories and models, is essential tothe design of a health program curriculumthat incorporates the strongest scientific andevidence-based knowledge to design moreeffective health promotion programs.The Challenge of Programmatic Integration. Acontemporary challenge in the field of healthpromotion involves integrating these “academic” and “grassroots” approaches by usingtheory and models to guide program planningand service delivery, while also grounding theseacademic models within the “real world” context of local community needs and preferences.Furthermore, in the spirit of the communitybased participatory research (CBPR) approach,and also to avoid a “one-size-fits-all” approach, itis desirable to obtain, “the best of both worlds,”by integrating the academic and grassrootsapproaches. This is accomplished by drawingfrom a combination of theories that use traditional individual-focused behavior-change

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 227Health Promotion in Latino Populationsstrategies, as well as by using social ecologicaland culturally relevant approaches (Glanz et al.,2002). In this regard, CBPR has served as a unifying translational framework, and under itsbasic social ecological model, it can be used as aframework for including cultural factors torestructure consumer environments, to eliminatebarriers, and to facilitate healthy behaviorchange (Castro & Balcazar, 2000; Castro &Hernandez-Alarcon, 2002).Anders, Balcazar, and Paez (2006) providean example of designing a CBPR program thatfeatures a Promotoras de Salud Modelas applied to cardiovascular disease risk reduction among Latinos/Hispanics. The Promotorasde Salud Model, a “natural helpers” model(Eng & Parker, 2002), builds from this ecological paradigm and incorporates cultural factors into a unified approach that addressesfactors hypothesized to effect changes inhealth-related behaviors (Anders, et al., 2006).Promotoras (lay health workers) aremembers of a local community who can berecruited and trained to administer a programor to offer health education or health promotion activities (Castro et al., 1995). They function as “cultural brokers” who serve thecommunity and can translate bidirectionallyfrom community to program and vice versa(Balcazar et al., 2006). Many programs havefound Promotoras to be useful adjuncts toprogram recruitment and implementationbecause they offer personalized support (personalismo) that removes barriers to healthcare and promote self-care behaviors amongwomen who are reached by these Promotoras(Reinschmidt et al., 2006). Often Promotorasenjoy greater trust from the local community(mas confianza de la comunidad). Confianza isa Latino cultural concept and refers to deeptrust that is earned through established caringrelationships. Confianza is often hard for newprograms and program providers to attain,whereas Promotoras can facilitate the processof gaining confianza from the community andfrom individual program participants.227Concepts of moderators and mediators.A core question in the design of health promotion programs is “To effect changes in behavior that enhance health, where and howshould we focus our intervention efforts?” Thedesign of effective health promotion programsbuilds on epidemiological and other scientificevidence, on “what works.” Such programdesign efforts are enhanced by understandingthe effects of moderators and mediators asintermediate “causal” factors that operatewithin the “causal chain” of events that produce health-related outcomes. A basic goal inthe science of prevention is to eliminate orreduce risk factors that lead to disease, and/orto increase or strengthen protective factorsthat safeguard against disease (Hawkins,Catalano, & Miller, 1992). To illustrate this,Figure 10.1 presents a model that describes thetemporal sequence of events involving typesof factors that occur in three stages:(1) antecedents, initial factors or starting conditions; (2) intermediate factors, that includemoderators or mediators; and (3) outcomes,that constitute results of this causal process.In this simple model (Panel A), the presenceof various setting conditions, for example,tobacco availability, operate as initial factorsthat directly prompt subsequent tobacco use.This model is presented in a compact and simplified form, given that in actuality a largercombination of factors operate in the mannersummarized by this simplified model. Forexample, factors such as socioeconomic status(SES) and an urban/rural community settingare presented here succinctly under the generalcategory of “Setting Conditions.” Thus, thephysical and social environment in which aperson lives presents specific “setting conditions” that can influence health-related behavior (D. A. Cohen, Mason, et al., 2003).In the case of a moderator variable (an effectmodifier), the influence of setting conditions ona health outcome can be moderated (can bemodified) by levels of a moderator variable.Examples of moderator variables include the

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 228228HISPANIC/LATINO POPULATIONSfollowing: gender—male, female; race/ethnicity—Hispanic, African American, white nonminority;levels of acculturation—low, bicultural, high;and traditionalism—traditional or modernistic.For example, based on epidemiologic surveydata, gender can operate as a moderator variable related to an outcome variable such asheavy alcohol use. For example, in response tosetting events (being in high school or being incollege), the rate of binge drinking (consumingfive or more drinks in a row) when in highschool (12th grade), and also when in college,Ahave been observed to differ consistently bygender. Epidemiological data confirm that forthe period of the past 2 weeks, young malesexhibit higher rates of binge drinking (33% inhigh school and 50% in college) relative toyoung females (23% in high school and 34%in college) (Johnson, O’Malley, Bachman,& Shulenberg, 2006). Thus, in this case, gender(male, female) operates as a moderator variable(an effect modifier) of the influence of the community setting (being in school) and the targeted outcome, binge drinking. As noted, thisAntecedentsModerators or MediatorsSettingConditionsModeratorsGender, Ethnicity, Level ofAcculturation, TraditionalismTobaccoAvailability (Risk orProtective Factor)BSetting Conditions* SES* Urban/RuralTobaccoAvailabilityTobacco Use(BehavioralOutcomes)MediatorsKnowledge—About tobaccorisks and consequencesNormative Beliefs—About useby peersValues—On desirabilityof tobacco avoidancePledges—Commitment to avoidtobaccoLife Orientation—Towardsachievement, healthSelf-Concept—Positive view ofself, building self-esteemSelf-Efficacy—Confidence inpersonal abilitiesSkills Training— Refusal skillsand Life skills trainingSupportiveRelationshipsFigure 10.1OutcomesBasic Models of Moderators and Mediators of Tobacco UseNo TobaccoUse/TobaccoAvoidance

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 229Health Promotion in Latino Populationsgender effect is observed both within a highschool setting and within a college setting.Furthermore, Panel B presents a set ofpsychosocial mediators, intermediary factorsthat can aid in preventing tobacco use amongadolescents. Mediators are “intermediate” or“in-between” variables that occur in timebetween the setting condition and the outcome(MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000).Mediators are part of a stagewise sequence ofevents that can be targeted for modification toattenuate this disease-related “causal process.”In a review of several intervention studies,Tobler (1986) noted that certain interventionscan operate as mediators that aid in reducingalcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) useamong adolescents. Along these lines, Hansen(1992) developed a comprehensive review ofvarious types of interventions to preventsubstance use among adolescents withinschool-based settings. These include (1) givinginformational knowledge; (2) changing values,normative beliefs, and/or life orientations;(3) making a commitment via a public pledgeto avoid ATODs; (4) enhancing self-concept,self-esteem, or self-efficacy; and/or (5) teaching refusal and life skills (see Figure 10.1).Within an effective prevention program, oneor more of these specific mediating interventions are ideally combined into a coherent“prevention intervention program.”It must be noted that solely providing factualinformational knowledge regarding the dangersof substance use has been shown to be a weakintervention and is usually not sufficient formotivating adolescents to avoid ATOD. In contrast, changing normative beliefs about theextent to which adolescent peers use tobaccomay change current misconceptions regardingtobacco use, and this operates as a more potentintervention of avoidance of cigarette and othersubstance use. Similarly, increasing a youth’sself-esteem or changing self-concept (self-image)of the self as a “nonsmoker” has a weak effect indiscouraging tobacco use. A more potent intervention involves increasing self-efficacy and229refusal skills for avoiding tobacco use. The strategy of increasing skills to avoid tobacco use, inthe form of life skills training (Botvin, Schinke,Epstein, Diaz, & Botvin, 1995) and refusal skillstraining (Kulis et al., 2005; Marsiglia, Kulis,Hecht, & Sills, 2004) have been shown to be thestrongest mediators that help youth avoid theuse of alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drugs.In this regard, Anders et al. (2006) have usedthe CBPR approach with Latinos to change relevant health-related “mediators” to preventchronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseaseor diabetes. This approach also includes attention to moderators that operate as contextualfactors (level of acculturation, immigrationstatus), social resources (social support, familycohesiveness, coping mechanisms), psychological responses (individual values or beliefs), andsocial supports (Promotora support and healtheducation), as well as addressing multiplebehavioral outcomes (diet, smoking, physicalactivity, alcohol consumption). The applicationof the Promotora model when integrated into aCBPR approach, and with a focus on changing“mediators,” contributes scientific capacity andcultural content to the design of health promotion programs. This also involves a focus onchanging culturally specific mediators, such asfamily traditionalism, ethnic identity enhancement, teaching traditional cultural norms, andbiculturalism, with the aid of Promotora-ledactivities.The Role of Staff Cultural CompetenceThe cultural competence of program staffalso serves as an important factor for increasingthe effectiveness of health promotion programs.Cultural competence refers to the capacity ofhealth professionals or of health service delivery systems to understand deep structure(Resnicow, Soler, Braithwait, Ahluwalia, &Butler, 2000) and to respond with cultural sensitivity to the health needs of a specific culturalsubgroup (National Alliance for HispanicHealth, 2001).

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 230230HISPANIC/LATINO POPULATIONS 3 Cultural ProficiencyMastery in cultural capacity 2 Cultural CompetenceUnderstands cultural nuances 1 Cultural SensitivityResponsive but stereotypical0 1 Cultural BlindnessIgnores cultural differences 2 Cultural IncapacityPassively discriminatory 3 Cultural DestructivenessActively discriminatoryFigure 10.2A Cultural Competence ContinuumCapacity for Cultural Competence. Figure 10.2presents a series of cultural attitudes and capabilities ordered in sequence according to progressive levels of cultural capacity. From thisperspective, the capacity for cultural competence varies along a graded continuum. A variation of this cultural competence continuumhas been proposed previously by variousscholars (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaacs,1989; Kim, McLeod, & Shantzis, 1992;Orlandi et al., 1992), and has been modifiedand expanded elsewhere (Castro, 1998).Along this cultural capacity continuum, thelowest capacity level is cultural destructiveness( 3), which involves overt discrimination andopenly destructive attitudes that emphasize the“superiority” of the dominant culture and the“inferiority” of indigenous cultures. Next onthis continuum, cultural incapacity refers topassive discrimination. This incapacity issuperseded by cultural blindness ( 1), an orientation which asserts that “all cultures andpeople are alike and equal.” Although universal equality is an ideal, it is not a reality, andthis perspective glosses over the presence ofhealth disparities and other forms of socioculturalinequity. Beyond these negative orientations,the first level of positive cultural capacity is cultural sensitivity ( 1). Cultural sensitivity ischaracterized by having a basic understandingand appreciation for the importance of culturalfactors in the delivery of health services.Beyond cultural sensitivity, cultural competence ( 2) involves the capacity to work effectively with members of a specific culturalgroup. Beyond cultural sensitivity, progressingto cultural competence requires greater depthin skills and experiences, thus moving beyonda superficial analysis of cultural featurestoward the capacity to understand and to workwith cultural nuances. Cultural nuances aresubtle but real cultural differences “that makea difference.” Understanding cultural nuancesfacilitates an accurate interpretation of thecommunications and behaviors exhibited by anethnic minority client. Thus, the healthprovider can accurately infer correct meaningfrom such thought and behavior, as interpretedwithin the client’s unique cultural context. Forexample, among Latinos, a culturally competent health program planner would understandand appreciate the role of personalismo, the

10-Kline-45556.qxd5/17/20085:21 PMPage 231Health Promotion in Latino Populationsimportance ascribed to trust and personalizedcommunications in interpersonal relationships.Accordingly, a culturally competent programplanner would incorporate aspects of personalismo into a health promotion program to makeit more culturally relevant for initiating andmaintaining program involvement amongLatinos.Finally, cultural proficiency, refers to thehighest and idealized level of cultural capacity.It is characterized by the health professional’sdeepest understanding of cultural issues andtheir nuances for a specific cultural group. Thiswould be reflected also in a health professional’s capacity for leadership in the design ofeffective health promotion interventions forethnic minority populations. As noted, culturalproficiency ( 3) is the highest expression of cultural capacity, and it serves as an ideal level ofcapacity, a state of high mastery that healthprofessionals should aspire to attain (Castro,1998). Here, it has been noted that culturalcapacity is a skills level that is specific for aparticular racial/ethnic or cultural group. Forexample, a Latino health provider may haveattained the level of cultural proficiency whenworking with Mexican American clients,although may only have developed the level ofcultural sensitivity when working with ChineseAmerican clients (Castro & Garfinkle, 2003).Origins of Health

In a quest to improve health promotion pro-gram effectiveness and staff capacity, cultur-ally enhanced health promotion programs can be referred to as being culturally relevant Formulate a conceptual framework for planning health promotion and educa-tion programs within several different Latino/Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Mexican,