Transcription

Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009), vol. 15, 57–64 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.004309Advocacy: time to communicateARTICLETom Harrison & Ruth DavisSummaryThis article offers an introduction to advocacy on behalf ofpeople with mental disorders and/or intellectual disabilities.It concentrates mainly on the issues related to independentspecialist advocacy, but refers to other forms also. The termis itself contentious, having different meanings in differentcontexts. Some of these controversies are outlined here.Inevitably, diverse interpretations imply varying practices, andthese too are illustrated briefly. Legislation and concordanceof expectations are both contributing to a set of standardsto which most advocates in the UK and Ireland will adhere.The requirements that such legislation makes of mentalhealthcare staff working with independent specialistadvocates are outlined, and the ethical dimension of mentalhealth advocacy is noted.Declaration of interestNone.This article sketches out some of the core issues ofadvocacy practice in UK mental healthcare. Thepotential range of this topic is huge, from individualcare to influencing government policy. Advocacyoccurs in a number of arenas, including the legalprocess, but in this article the discussion is limitedto the clinical setting. We hope to illustrate someof the key issues of mental health advocacy andto show how those who act as advocates can besupported and helped in their often difficult work.We strongly contend that advocacy benefits themental health of service users in the longer term,although in the short term it may prove onerous forboth advocates and psychiatric staff.Why advocacy?The central tenet of advocacy in healthcare is thatservice users should be enabled to speak up ontheir own behalf and empowered to take a leadin the decision-making process. The various typesof advocacy are held together by the ‘matrix’ ofself-advocacy: speaking up for oneself (Campbell1991: p. 155).There are many ways in which advocacy canbenefit mental health: it improves the individual’sunderstanding of their situation, enables their viewsto be heard, ensures that they have the opportunityto be partners in their care and increases theirautonomy. Advocacy promotes the rights of thosewho suffer discrimination because of their age,disability, sexuality, gender or culture. It has beenargued that advocacy also ensures the improvingquality of the care system (Wolfensberger 1977: p.16). This opinion is echoed in the World HealthOrganization’s statement that: ‘Advocacy is animportant means of raising awareness on mentalhealth issues and ensuring that mental health ison the national agenda of governments. Advocacycan lead to improvements in policy, legislation andservice development’ (World Health Organization2003: front cover).People with intellectual disabilities (also knownas learning disabilities in UK health services),physical impairments, mental health disorders,and also children and older people, often find itdifficult to make their voices heard when decisionsconcerning their lives are made. Their reliance onothers and concomitant social isolation can leavethem vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.It is in this setting that advocacy within the UKis expanding. Despite the often fragile funding forits provision, varying approaches and consequentlack of coherence, advocacy is persistent. It isfirmly embedded in policy, including the MentalHealth Act 2007 and Mental Capacity Act 2005for England and Wales, the Mental Health (Careand Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 and the UK’sNational Standards for the Provision of Children’sAdvocacy Services (Department of Health 2002).In Ireland, the Citizens Information Act 2007 hasmandated the Citizens Information Board to provideadvocacy targeted at people with disabilities ingeneral (Ireland Government 2007).We carried out a range of literature searches inthe preparation of this article and found that theavailable publications are largely illustrative and/or polemical. We have attempted here to distil themain themes and issues arising and to illustratea model of advocacy in mental healthcare thatis accepted by the large majority of practitionersin the field in the UK. Various words are usedto identify the individual on whose behalf theadvocate is working – service user, client, patient,partner – and we use them interchangeably.Tom Harrison is Consultant Psychiatristin Psychiatric Rehabilitation withBirmingham and Solihull Mental HealthTrust. He was Chair of the Royal Collegeof Psychiatrists’ Working Party onAdvocacy. Ruth Davis is Manager ofBirmingham Citizen Advocacy, Southside,Sparkbrook, Birmingham, UKCorrespondence Dr Tom Harrison,Yewcroft Mental Health Resource Center,Court Oak Road, Harborne, Birmingham,B17 9AB. Email: tom.harrison@nhs.netWhat is advocacy?In modern English, advocacy is commonly under stood to mean speaking, pleading or interceding forsomeone else. In its report on patient advocacy, theRoyal College of Psychiatrists states that ‘In relationto people with mental health problems or 9 Published online by Cambridge University Press

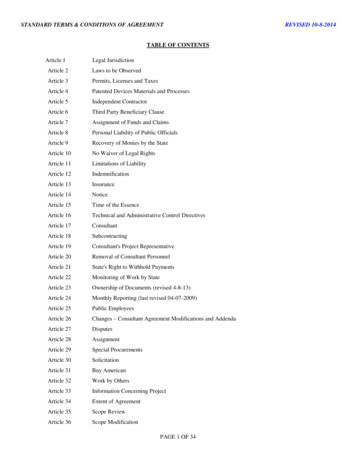

Harrison & Davisdifficulties, it has the rather different meaning ofhelping people to be heard, and ensuring that whatthey say influences the decisions of clinical staff’(Royal College of Psychiatrists 1999: p. 6).In practice, the word is used to cover a widerange of activities, resulting in obfuscation ofthe core concerns (World Health Organization2003: p. 46). This lack of a clear interpretationhas delayed attempts to achieve consensus onwhat is good practice and how it may be evaluated (Henderson 2001: p. 14). Its meaning here isrestricted to those activities carried out within aset of principles outlined in Box 1, and carried outby specific individuals employed, or volunteering,for the purpose. This limitation contrasts it withwhat Wolfensberger (1977) describes as ‘cheeseadvocacy’, referring to a commercial that suggestsone can take any kind of food and add cheese to it.There is, he argues, a similar tendency to describeany form of verbal support given to the individualas advocacy, irrespective of whether the person haseven been consulted.The word accumulates meanings according tothe agenda of the person using it. It can be usedto support conflicting ideologies and practice, withlittle or no reference to the views of the peoplesupposedly being represented (Milner 1986). Anexample that illustrates Wolfensberger’s concernsis when individuals, whether they be staff, friendsor family members, acting as advocates promotetheir own preoccupations (Caras 1998).Wolfensberger, writing in Canada, believes thatmerely speaking on behalf of another is not enough.Advocacy, he writes, ‘implies a vigor, a vehemence,a commitment, . a high cost, often in the formof risk’, with concomitant ‘hostility from others,taunts, being considered foolish or crazy, loss ofincome, loss of job, loss of health, physical hurt andBOX 1 The key characteristics of advocacy Empowering The ideal is to enable individuals to speak for themselves (or if that is not possible, toensure that their point of view is acknowledged and understood), allowing them to make informedchoicesIndependent Advocates must not be employed by the organisations making decisions regarding thepartner’s life. They must be able to express their partner’s views without prejudice to themselves.Inclusive Everyone should be able to access an advocate, irrespective of any aspect of their personalsituation, including their ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual preference or ageImpartial Advocates must not judge their partner. They might be the only person who can representtheir partner’s point of view and they must present it as valid and as the truth for that personConfidential All information shared between the advocate and their partner is confidential, exceptwhere harm is threatened to anyone. Any information given to the advocate will be shared with theirpartner, in all but exceptional circumstancesFree Advocacy services must be free to the recipient(Modified from Barnes 2002)58https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.004309 Published online by Cambridge University Pressviolence – perhaps even of death’ (Wolfensberger1977: p. 18).This belief is expressed only a little less passion ately by some British commentators: ‘It is not theprofessional deciding what is best, but the genuineattempt to get into the mind of the patient/client,which is the basis of genuine advocacy’ (Brandon1995: p. 35). Tyne recommends that the advocatemust be prepared to be excluded, along with theperson who is their protégé. He argues that by‘taking a responsibility in someone else’s life, onehas to be prepared to suffer the consequences’,contrasting this with the professionals who ‘havefor a long time “taken responsibility” in the livesof disabled people, without of course having tosuffer the consequences – just as kings and princeswere rarely brought to book’ (Tyne 1994: p. 253).Thomas and Bracken echo this opinion, arguingthat advocacy ‘has a key role to play in mediatingthe dangers of unchecked medical paternalism inpsychiatry’ (Thomas 1999).Such fiery rhetoric can leave psychiatrists troub led. Gamble (1999) worried about the ‘destructiveideology-driven power’ of some advocacy move ments. Tyrer noted that his psychiatric colleagueswere suspicious and sometimes overtly hostile ofadvocacy and patient empowerment (Tyrer 1989).However, he emphasised that clinicians should notform ‘defensive bastions’ against patient power.In general mental health practice, however, theexperience is usually less charged. Having anadvocate attend a patient review can be approp riate and helpful (personal experience, T.H.). Thefollowing extract shows good practice in imple men ting independent mental health advocacy:As an advocate, I have found it important to build upa good working relationship with ward staff. I do thisby meeting with staff at team meetings to tell themabout the service and I sometimes do a presentationon advocacy at staff inductions. However, the bestway is to keep talking with people individually.I find that students working on the wards have agood understanding of advocacy and are curious tolearn about my role. On the other hand, qualifiedstaff respond to me in different ways – some arewhat I call advocacy friendly and others less so.(Barnes 2007)Psychiatrists canvassed in the preparation ofthe College’s report on patient advocacy described‘numerous positive experiences’ (Graham 1999).They found diffi culties only when the advocatelacked sufficient training or independence, orwhen ‘an adversarial situation had been allowedto arise’ through inadequate services or poorcommunication. A more recent study foundincreasing acceptance of advocates by mentalhealth staff, although the authors note that thereis still some way to go (Carver 2005).Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009), vol. 15, 57–64 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.004309

Advocacy: time to communicateHistoryThe advocacy movementOne of the earliest self-advocacy documents onrecord is the Petition of the Poor DistractedPeople in the House of Bedlam in 1620 (Brandon2000). Over two centuries later, in 1845, RichardPaternoster established the Alleged Lunatic’sFriend Society. He recruited John Perceval, who,following 3 years’ incarceration, wrote vocifer ously about his maltreatment. They introducedthemes that even now recur: demands for a voice indecisions about care, campaigning for change andalignment with radical politics (Hervey 1986).In the 20th century, self-advocacy again cameto the fore in relation to people with intellectualdisabilities in Sweden and the USA in the late1960s. In the UK, two ‘participation’ conferenceswere held in the early 1970s by the Campaign forPeople with Mental Handicaps. This organisationgrew with the development of many local andregional groups throughout the country afterthe formation of People First in London in 1984(Atkinson 1999: pp. 9–12).The citizen advocacy movement, born in theUSA in the 1960s, became established in the UKin 1981 with the formation of the AdvocacyAlliance, for people with intellectual disability.The Alliance came about through a coalition offive major voluntary agencies (Mind, Mencap, Oneto-One, the Spastics Society and the LeonardCheshire Founda tion). Advocacy has spread toother arenas, including old age, mental disorder,deafblindness and hearing impairment. By 1987,60% of adult training centres for people withintellectual disabilities had some form of selfadvocacy group (Brandon 1995: p. 67).Self-advocacy for people with mental healthproblems was established in the UK in 1985 throughthe formation of Survivors Speak Out, influencedby workers in The Netherlands (Barker 1986). Inthe 1990s, there were over 900 Survivors SpeakOut groups operating, although there has been asubsequent declined in numbers (Wallcraft 2003).One of these, the Nottingham Advocacy Group,integrated three components – paid advocacy,patients’ councils and a citizens advocacy scheme –into one service. This has been praised as a modelsystem (Mullender 1991: p. 6).National policy and legislationThe first national strategy for people withintellectual disabilities in the UK was introducedby the Welsh Assembly (Welsh Office 1983). Theinclusion of funding for self-advocacy increased thenumber of self-advocacy groups in the Principalityfrom 2 in 1985 to 58 in 1995 (Whittel 1998).Valuing People, the government White Paper onservices for people with intellectual disabilities inEngland, placed considerable emphasis on bothadvocacy and self-advocacy (Department of Health2001a). Recognising that both were unevenlydeveloped across the country, it committed 1.3million a year for the next 3 years to correct this.By 2004, there were 43 advocacy organisationsfunded through the grant (Greig 2004).The Mental Capacity Act 2005 for England andWales launched the Independent Mental CapacityAdvocate service. Some critics considered that itwas implemented hesitantly, and raised concernsabout the short-term nature of the associatedfunding (Gillen 2007). There still appears to belittle evidence of evaluation of the service. Informalevidence that we have been given indicates thatimplementation is patchy and that the independentadvocates have in some cases largely endorsed theopinions of clinical staff.One of the provisions of the Mental Health (Careand Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 is an independent advocacy service for people with mentalillness, dementia, intellectual disability and personality disorder (Scottish Government 2005).The Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliancehas now published a code of practice, and a setof principles and standards (Scottish IndependentAdvocacy Alliance 2008a,b). There is no separateadvocacy service for people lacking capacity, as inEngland and Wales.In Ireland, the 2004 Comhairle (Amendment)Bill delegated to the Citizens Information Board(then known as Comhairle) the responsibility forproviding services for all people with disabilities.The Board has promoted a three-stranded strategicapproach comprising a personal advocacy service,a programme of support for community andvoluntary organisations, and a community visitorsprogramme.The Mental Health Act 2007 for England andWales has followed the Scottish lead by institutingthe right of detained patients to have access toindependent mental health advocates, who ‘willhelp patients understand the way the MentalHealth Act applies to them, and what can andcannot be done as a result’ (Department of Health2008b). Unfortunately, the shine has been takenoff this by the fact that, although the act tookeffect from November 2008, the section relating toadvocates will not be introduced in England untilApril 2009, causing some dismay (Shepherd 2008).This delay did not affect Wales, where the servicewas implemented in November 2008. Many staffin psychiatric services have expressed anxietiesregarding patient advocacy, but it is hoped thatthese will be assuaged by professionalisation of theAdvances in psychiatric treatment (2009), vol. 15, 57–64 doi: pt.bp.107.004309 Published online by Cambridge University Press59

Harrison & Davisadvocacy service, with the provision of trainingand development of national standards for suchadvocates (Carver 2005).Advocacy in practiceIn discussing the practice of advocacy in mentalhealthcare, We will consider three areas: thenature of advocacy and its practitioners, the role ofhealthcare staff, and the diversity of patients andof provision.Box 2 Independent mental health advocacyAvailable only to people detained under the Mental Health Act2007, conditionally discharged restricted patients, individualssubject to guardianship or supervised community treatmentThe advocate’s role is to: help patients to obtain information about and understand: The nature of advocacy and its practitioners The individual and the group advocate A mental health advocate may be one of a rangeof individuals: the person themselves (the selfadvocate), a friend or family member, someonewith specific training in advocacy or a lawyer.Wolfens berger (1977) promoted the concept of the‘citizen advocate’, a volunteer who takes on the roleas part of their sense of responsibility as a memberof society, who would befriend their protégé overmonths or years. This concept is hotly contestedby those who argue for ‘peer advocacy’, where thesupporter has used similar services and can employthis experience to understand the individual better(Brandon 1995: pp. 92–99).Advocacy can also be carried out by peopleworking together in a group, for example throughorganisations such as Survivors Speak Out andPeople First.The purpose of advocacyAdvocates may act for the individual or for thegroup. Their aim may perhaps be to improvecare, to protect safety or rights, to demand furtherresources or to influence policy. At the individualclinical level, the client may discuss with theadvocate their own care, their participation withinthis and their ambitions for themselves. Theymay also need an advocate’s support to argue forappropriate financial benefits or housing. At thegroup level, advocates may work with others toeffect changes to local or national services, or torepresent client groups in arguing for nationalpolicy reform.The advocate’s investment: specialist advocatesIndependent mental health advocates Advocacy demandstime and dedication, and it is increasingly commonfor advocates to be paid for their services. A reportcommissioned by the Department of Health on goodpractice in advocacy (Barnes 2002) made recom mendations for an independent specialist mentalhealth advocacy service in England and Wales.Subsequent changes to mental health legislationin the UK gave patients, particularly those subject60https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.004309 Published online by Cambridge University Press their rights under the Mental Health Act Actthe rights that other people have in relation to them underthe Actthe particular parts of the Act that apply to themany medical treatment that they are receiving or mightreceive, and the rationale, legal authority and safeguards for ithelp patients to exercise their rights, including representingthem and speaking on their behalf if necessarysupport patients to ensure that they can participate in decisions(Department of Health 2008a)to conditions of the respective mental health andmental capacity acts, statutory right of access toadvocacy, bringing with it the requirement forstatutory state funding. The advocates in thesesituations are usually professional, salaried,trained and subject to specific standards of prac tice. Working with each client for a limited periodof time and for a particular purpose, they do notoffer prolonged contact or befriending. They may ofcourse work with the same individual on a numberof occasions, but each will be counted as a separateepisode. Their role is summarised in Box 2.The distinctions between different formsof advocacy are more evident in print than inpractice. Overlaps occur throughout. BirminghamCitizen Advocacy, for example, employs paidadvocates to work on specific issues and recruitsvolunteers to support individuals over the longterm. This is an example how the original citizenadvocacy approach has been modified in the lightof the development of other provision, in this casespecific befriending services.Independent mental capacity advocates Enabling someoneto express their own views is clearly less possible iftheir mental capacity is diminished. Independentmental capacity advocates (Box 3), because ofthe specific nature of their clients in most cases,will often have to rely on their own judgement.Where the individual is unable to communicateand has left no evidence of what their preferenceswould have been, the advocate has to attempt tounderstand, and ensure that staff have taken intoaccount, what they believe their partner wouldhave wanted. The decision maker has then to makea decision in the ‘best interests’ of the individual,taking this into account (Lee 2007).Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009), vol. 15, 57–64 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.004309

Advocacy: time to communicateBox 2 Independent mental capacity advocacyProvided for anyone over 16 years of age who has no one ableto support and represent them, and who lacks capacity (underthe Mental Capacity Act 2005) to make a decision about along-term care move, serious medical treatment, adult protectionprocedures or a care reviewThe advocates role is to: ascertain, if possible, the individual’s hopes, beliefs, andexpectations and ensure that these are considered by thedecision makerrepresent the person, if instructions are not available, askingappropriate questions and ensuring that their rights are upheldand are central to the decision-making processgather, research and evaluate all possible information from allwho know the client well and from relevant professionalsensure that the person’s civil, human and welfare rights arerespectedAudit and, if necessary, challenge the decision-making process(Speaking Up 2007)Where there is an advance directive, clearly theadvocate has to respect its decisions. A client’sdoctor may use the Mental Health Act to overridethose decisions, but the advocate must neverthe less represent them to the best of their ability.Interestingly, there is some evidence that advancecrisis plans jointly drawn up by the staff workingwith the individual reduce the use of the MentalHealth Act in admissions (Henderson 2004). Anadvocate’s contribution to this process would beinvaluable.The professionalisation of advocacyIt is now widely recognised that independenttrained advocates should work to accepted stan dards of practice, and receive training and personalsupport in their role (UK Advocacy Network 2001;Comhairle 2003; Sollé 2006). Good practice guide lines set out core competencies in ethical practice,knowledge, the advocacy process, advocacy skillsand attitude (Barnes 2002: pp. 35–36). The lastincludes tenacity, patience, reliability, desire toproblem solve and willingness to learn. Theguidelines regard supervision and support to beessential and, as mentioned above, recommendgood professional relationships with care staff.Training and support, of course, require sig nificant financial resources, and there is greatconcern among the providers of advocacy servicesabout the often temporary and vulnerable natureof the commissioning arrangements in the UK(Atkinson 1999: p. 14; Gillen 2007; Newbigging2007: p. 110).The role of healthcare staff in advocacyFor mental healthcare staff two main areas ofconcern arise. First is the necessity to assist theindependent advocate in their work, and second isthe advocacy role that they themselves take on.Staff must understand the nature, and impor tance, of advocacy. They must be aware of whatlocal services can provide and must enable peoplein their care to access them (Sollé 2006: p. 15).However, a small survey of 14 clinical staff workingin northern England revealed poor understandingof these issues (Lacey 2001).The practicalities of assisting the advocateThe Mental Health Act and Mental Capacity Actlegislation gives staff explicit responsibilities toensure that a private room is available in which theadvocate can interview their partner and that theadvocate can interview any person who is concernedwith their partner’s treatment. With their partner’sagreement, the advocate must be allowed accessto medical and social services records. Where thepartner is unable to express such an opinion, theindividual holding the records must agree, where itis appropriate and relevant, that the advocate canaccess them (Mental Capacity Act 2005).Staff should inform the advocate in advanceabout all relevant meetings and ensure that theyfeel welcomed if they attend. Although advocatesmay be invited to attend meetings, the spirit offacilitation may be lacking: one survey reportedthat ‘Advocates often have their time wastedattending meetings invariably organised for theconvenience of others, or waiting around for a slotin an otherwise very long meeting’ (Newbigging2007: p. 114).The advocate must be allowed the time andoppor tunity to carry out their role, includinghaving appropriate access to their partner and tothe information relevant to the case. In interviews,adequate time should be allowed for the advocateto rephrase questions for their partner and toencourage that person to speak for themselves.Where the partner has difficulties in making orunderstanding decisions, it is important that theadvocate is respected for their attempts to discernwhat the individual’s wishes might be.Advocacy enhances an individual’s capacity toquestion, their ability to refuse a course of actionand their autonomy.Ethical dilemmas of independent advocacyStaff often find it hard to understand and acceptthe full implications of the principles underlyingadvocacy. One of the most difficult is the advocate’sobligation to remain impartial. A patient mayAdvances in psychiatric treatment (2009), vol. 15, 57–64 doi: pt.bp.107.004309 Published online by Cambridge University Press61

Harrison & Davisrequest objectively unreasonable, and even risky,options, but the advocate is not there to be cajoledinto encouraging them to take a different view.An advocate must, whatever their own personalopinions, represent those of their partner. AsThomas & Bracken express it, someone ‘steadfastlyrefusing a course of treatment, supported by anadvocate, against the will of the clinical staff is oneof the most difficult ethical dilemmas to resolve’(Thomas 1999).Those responsible for providing care or treat ment are inevitably influenced by safety concerns,social expectations and their own value system. Itis, of course, always the aim to have a shared visionof how to proceed; but it is not inevitable. Theprocess of understanding an individual’s viewpointentails recognising the powerlessness, loss of selfesteem and resultant frustration of being someonewho has had to, or even been forced to, seek help.The sense of criticism, although often not intended,that staff may experience adds further tension.Particularly in these situations the advocatethemselves may experience considerable distress(Sollé 2006: p. 27). This should be acknowledgedwithout trying to persuade them to modify theirpartner’s views.The primacy of the advocacy relationshipextends to confidentiality. Except in extraordinarycircumstances, an advocate is bound to sharewith their client any information that they receiveabout them. This includes any clinical informationimparted by staff.The advocacy role of healthcare staffThose concerned with the welfare of people withmental health disorders and intellectual disabilitieshave long engaged in speaking out on their behalf.Some professions include advocacy as part of theirremit. Nurses in the UK are enjoined to ‘promotethe interests of patients and clients’ (Nursing andMidwifery Council 2004). Social workers are alsodeemed to have a ‘clear responsibility to act asadvocates for their clients’ (Bateman 2000). Itmay be proper to distinguish this advocacy rolefrom any suggestion that staff are in themselvesadvocates. This distinction may seem to someunnecessarily fine, but it is important to recognisethat professionals are always compromised by theirpowerful influence over their patients’ or clients’care. There is always a confusion of loyalties foremployees of the system that is providing a service.This is not a criticism of the integrity of clinicians.It is merely a recognition of the difficulties implicitin the situation. Where decisions are being madeabout treatment, only an independent advocatecan truly support the case of the individual underconsideration. However, people rarely request62https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.004309 Published online by Cambridge University Pressadvocates to support them, putting their trustin individual staff and seeking their support inpromulgating their views.Clinicians also perform advocacy roles outside ofthe clinic. Many have achieved a great deal throughpromoting their patients’ interests. It is important,though, to acknowledge that such advocacy carrieswith it the temptation to act on behalf of the peoplethat they are working for without attempting to findout their real wishes. It is always best to encourageindividuals to make their own case and to assistthem in developing the skills to achieve this.Invited participation in forums run by peopleusing services can both enhance their influenceand encourage them to share opinions about whatthey really hope for. We have found that decisionmakers in the health services are more likely tolisten to an argument when it comes from a numberof sources rather than just one. The expression ofservice user views alongside those of clinicians canenhance m

others and concomitant social isolation can leave them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. It is in this setting that advocacy within the UK is expanding. Despite the often fragile funding for its provision, varying approaches and consequent lack of coherence, advocacy is persistent. It is firmly embedded in policy, including the Mental