Transcription

Strengthening UtilitiesThrough Consolidation:The Financial Impact

PrefaceThe US Water Alliance and the UNC EnvironmentalFinance Center are committed to advancing fact-based,common-ground solutions to our nation’s most pressingwater challenges. Currently, the water sector is extremelydiffuse. There are tens of thousands of water utilitiesand authorities in America. This is also a time of growingcomplexity and unprecedented change in the water sector.Collaboration and cooperation will be essential tosecuring our nation’s water future. As the adage goes—there is strength in numbers.Consolidating water services is one of many potentialapproaches that enables utilities to meet today’s needsand tomorrow’s demands. Pooling resources and stream lining operations and decision-making can enhanceefficiency, but to get there, leaders need a clear pictureof the payoff to justify the journey. Information aboutconsolidation options and financial impacts is essentialto understand what this approach can do to increasefinancial stability in the water sector.To address this need, the US Water Alliance and theEnvironmental Finance Center teamed up to synthesizethe body of evidence about the financial outcomes possiblewith water utility consolidation. This report examinesthe experiences of eight communities who consolidatedutility service in different ways and for different reasons.Breaking down silos in water will require skilled leadershipand deep understanding of the tools and methods at ourdisposal. To that end, we hope to grow understanding byproviding insight about what financial impacts communitiesmight expect through consolidation.Jeff HughesDirector, UNC EnvironmentalFinance CenterStrengthening Utilities through Consolidation: The Financial ImpactRadhika FoxChief Executive Officer,US Water Alliance1

AcknowledgementsThe US Water Alliance and UNC Environmental FinanceCenter would like to thank Erin Riggs, Project Director atthe Environmental Finance Center, and Emily Simonson,Program Manager at the US Water Alliance, for theirsubstantial research and writing contributions. We alsowant to thank Katy Lackey, Program Manager at the USWater Alliance, and graduate student researchers, KatyHansen and Laura Landes from Duke University andKrysten French from the University of North Carolina,who contributed to this project.This report was informed by an experienced set of watersector leaders. Thank you to all those who took the timeto be interviewed and provide feedback on this report,including: C. Tad Bohannon, Chief Executive Officer, CentralArkansas Water Jesse Cain, City Manager, City of Colusa Maureen Duffy, Vice President, Communications andFederal Affairs, American Water Jim LaPlant, Chief Executive Office, Iowa RegionalUtilities Association Shelli Lovell, General Manager, Marshalltown WaterWorks Kenny Waldroup, Assistant Public Utilities Director,City of Raleigh John Walton, Director of Marketing, Logan ToddRegional Water Commission2US Water Alliance

Table of Contents4 Introduction5 Part One: A Synthesis of Financial Impacts91114182125303336Part Two: Financial Case StudiesCentral Arkansas WaterCitizens Energy GroupCity of ColusaCity of Raleigh Public Utilities DepartmentHampton Roads Sanitation DistrictIowa Regional Utilities AssociationLogan Todd Regional Water CommissionNew Jersey American Water40 About the US Water AllianceAbout the UNC Environmental Finance Center41 Notes42 AppendixStrengthening Utilities through Consolidation: The Financial Impact3

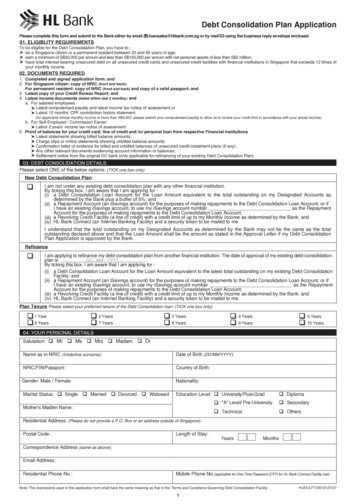

IntroductionThe water sector is at a crossroads. Most water systemsin use today were built for communities that look differentthan the ones they now support. Population and demo graphic shifts, modern water quality threats, aginginfrastructure, and related challenges are bearing downon water systems. Providing affordable, reliable, andhigh-quality water service is a difficult business. Considera few salient facts: Water infrastructure is aging and failing. In 2017, theAmerican Society of Civil Engineers gave the nation’swater infrastructure a “D” grade and the nation’swastewater infrastructure a “D .” Significant funding is needed. The American WaterWorks Association estimates drinking water systemsneed to invest 1.7 trillion in infrastructure over thenext 40 years.1 The Environmental Protection Agency’sneeds survey estimates the United States requires 271 billion for wastewater and stormwater needsover the next 20 years.2 Affordability is a growing concern. Water rates andfees are already rising and outpacing the ConsumerPrice Index.3 New investments contribute to growingconcerns about water service affordability.The water sector faces many barriers to addressing thesechallenges. One challenge is fragmentation. There arecurrently over 51,000 regulated community water systemsowned and managed by thousands of entities rangingfrom large metropolitan cities to mobile home parkowners.4 Furthermore, there are nearly 15,000 wastewatertreatment plants, and over 1,000 stormwater utilities inAmerica.5;6 By comparison, the United Kingdom only has32 regulated water utilities and Australia only has 82water suppliers.7 On average, each utility in Australia andthe UK serves a much greater percent of the populationthan do systems in the United States.In this landscape, water utilities may struggle to maximizebenefits from their investments, save costs by operatingat scale, and tackle challenges efficiently. Luckily, thereare many ways utilities can collaborate with one anotherto streamline and improve water service. Utility partner ships can take many forms—from informal collaborationagreements to merging the financial and governancefunctions of separate entities. For example, some utilitiesundertake joint contracting for services which can lowerprices; others partner on projects like emergency planning;some may have franchise agreements in place to sharewater supply.Figure 1Approaches to Collaboration Between ingImposedDistricts,RegionalizationUS Water AllianceConsolidatedEntites,UnifyingGovernance

Consolidation is just one approach on this spectrum ofoptions for how utilities can work together to provide highquality water service. Water utility consolidation occurswhen two or more distinct legal entities become a singlelegal entity operating under the same governance,management, and financial functions. It may or may notinclude physically interconnecting assets. Consolidationalso occurs at the regional level even when assets arespread out by merging the governance, management, andfinance supporting geographically spread assets.Current research and information on consolidation is lessrobust relative to other ways in which utilities engage inregional collaboration. Communities need access to facts,data, and information to support informed decisionmaking. Towards that end, the US Water Alliance and theEnvironmental Finance Center at the University of NorthCarolina developed this report focused on the financialoutcomes utilities have realized through consolidation. Thisreport focuses on the impacts of different consolidationarrangements on customer rates, utility budgets, and debt.In some of the case studies, we also touch on economicimplications, such as the broader costs and benefits tosociety beyond the utilities and customers involved.Researchers at the UNC Environmental Finance Centeridentified and profiled a range of different consolidationmodels from across the country and studied the financialimpacts resulting in each case. A team of graduatestudents from Duke University provided additional researchincluding preparing a literature review that inventoriedpast research on consolidation.Defining Key TermsTypes of ConsolidationConsolidation occurs when two or more legal entitiesbecome one operating under the same governance,management, and financial functions. Consolidationcan include: Direct Acquisition, where a higher-capacity utilityacquires the assets, operations, and customersof another system and absorbs them into its existinggovernance, operational, and financial frameworks. Joint Merger, where two or more relatively equalpartners both adjust governance, operations, andfinancial frameworks to create a new entity that is ownedand controlled by the previously separate parties. Balanced Merger, where two or more entities consol idate with the goal of establishing a governancestructure that provides a basis for at least some directparticipation by the pre-existing utility in futuredecision-making.Regionalization and Regional AgreementsRegional approaches can also generate financial efficiency.These approaches do not combine legal entities but dopool utility resources, buying power, and technical expertiseto do more across a wider area than a single utility coulddo alone. In some cases, utilities may develop regionalpartnerships to collaborate on issues of joint interest,like workforce development. In other cases, regionalizingcould put one organization in charge of a particularproject or function that takes place across many utilities’service areas.With this report, the US Water Alliance and the Environ mental Finance Center aspire to fill the gap in currentresearch about the economic attributes associated withdifferent consolidation models. We hope this researchhelps communities understand the opportunities, tradeoffs, and financial impacts of consolidation.Strengthening Utilities through Consolidation: The Financial Impact5

Part One:A Synthesis of FinancialImpactsEconomies of Scale and Operating EfficienciesIn rural and urban settings, consolidation often resultsin greater economies of scale. In other words, water,wastewater, and stormwater services involve dozens ofseparate business functions that can benefit from beingspread over larger groups of customers.Consolidation can be a tool to create fewer, moreindependent, high-capacity utilities—potentially benefitingratepayers, local communities, and the broader watersector. However, communities need to weigh the benefitswith the challenges of consolidating utilities. For example,consolidation can trigger a cascade of avoided futurecosts to a local utility, which can then be passed on tocustomers in the form of savings. But, in the near-term,some communities will face increased costs to addressregulatory requirements and infrastructure investmentbacklogs. Communities need to look at financial factorsover time and in local context. In some cases, utilityconsolidation may have more to do with improving servicethan reducing costs.Consider operating expenses. Reading 50 meters permonth usually costs significantly more per meter thanreading 50,000 meters. Maintaining a large network ofassets rather than a smaller network of isolated assetscan also be cost-effective. Similarly, the prices smallersystems pay for chemicals and services are often muchhigher than the price paid by their larger counterparts.Essential chemicals, such as chorine, are available inmuch lower unit costs when bought in bulk.Financial BenefitsCommunities contemplating whether to consolidateutilities need to consider a multitude of information. Themost critical pieces are knowing what the value to thecommunity would be and how long it could take to realize.Assessing, estimating, and quantifying benefits may bedaunting, but doing so is essential to know whetherbenefits outweigh the costs and challenges. Benefits canbe spread among customers, systems involved, and thebroader economy. Potential financial benefits from waterutility consolidation include: Economies of scale and operating efficiencies; Increased access to capital at a lower cost; Lower or equal customer rates for a specified levelof service; Revenue stability; Reduced exposure to regulatory penalties; Improved planning and risk management; and Increased opportunities for economic development.6Staffing costs also benefit from economies of scale.Salaries for highly-trained managers have increased intandem with the regulations and environmental challengesthose managers are entrusted to handle. A skilled utilityprofessional serving 500 customers may be equally ableto serve a community with 5,000 customers. In this case,spreading the cost of a professional manager over morecustomers can reduce costs.Increased Access to Capital at a Lower CostWater is a capital-intensive enterprise. There are highcosts associated with investing in and maintaining thevast infrastructure that water utilities operate. Costs areclimbing with the need to upgrade, retrofit, and makesystems more resilient. Several case studies in this reportshow that consolidated utilities can access capital frominvestors at a lower cost. When utilities consolidate, theypool resources to serve larger customer bases. As aresult, consolidated systems may receive better termsand interest rates on bonds and commercial loans fromprivate capital markets to fund capital improvements.8Regional consolidation may also qualify systems forsubsidized public funding options not available for nonregional efforts. These sources of funding vary by state butmay include subsidized State Revolving Fund loans orstate planning grants that can save communities moneyon principal costs and interest payments.US Water Alliance

Lower or Equal Customer Rates for a Specified Levelof ServiceOnce a water utility reduces or minimizes capital andoperating costs, the level of funds needed fromcustomers may change. In many situations, financialbenefits from consolidating are tempered by ratesneeding to rise to address overdue issues and pay thenear-term costs of consolidating. However, in lesscommon situations, customers may see immediate orshort-term rate reductions.Rate parity across customer bases is typically a morecommon goal than rate reductions. Customers within asingle geographic region served by multiple water serviceproviders might pay different prices for the services theyreceive. Carefully structured consolidation can equalizerates among customers within a service area and slowfuture rate increases for all involved.Revenue StabilityThe water sector is experiencing major changes in itsrevenue business model.9 Utility consolidation can makesystems less vulnerable to revenue shortfalls. Consolidatedsystems that tie together more diverse water usersmay be able to mitigate revenue fluctuations and spreadthe cost of filling shortfalls over a larger customer basewhen they do occur. Several case studies in this reportdemonstrate how systems can maintain revenue andfully optimize capacity through consolidation. This modelworks particularly well if systems consolidate whenconsidering new investments. While consolidation mayalleviate some revenue challenges, utilities should not viewconsolidation as a fail-safe way to protect communitiesfrom inherent risks like overoptimistic projections, largecustomer losses, or the cost of retrofitting and buildingsystems resilient enough for future circumstances.Strengthening Utilities through Consolidation: The Financial ImpactReduced Exposure to Regulatory PenaltiesCommunities often consider consolidation becauseof regulatory pressure, placing more weight on avoidingunwanted penalties than on saving revenue. From treat ment facilities to ailing collection systems, consolidationis increasingly becoming one of the main solutions forachieving cost effective regulatory compliance. Consol idating utilities can shift regulatory responsibility,streamline and reduce the cost of regulatory approvals,and, in some cases, provide immediate regulatoryfinancial relief.Improved Planning and Risk ManagementWater service keeps local economies running, communitieshealthy, and the environment safe; that means the risksutilities plan for and manage carry significant costs.Consolidation has allowed many utilities to mitigate riskand benefit from integrated planning. A particular risk,like diminishing water supply, may even be the driver forwhy communities consider consolidation. The organiza tional and water resources planning processes under aconsolidated utility can also lead to a more comprehensive,less piecemeal strategy than when spread acrossmultiple systems or localities.Increased Opportunities for Economic DevelopmentSome financial savings are apparent on water utilitybudgets, rate sheets, and other financial documents.Other benefits may occur off the books in the broadercom munity, despite being direct and visible outcomes fromconsoli dating water utilities. For example, commu nitiesfacing water shortages or lacking wastewater servicescan struggle to grow or develop their local economies.Businesses hesitate to locate in places where access towater supply or quality of water services are in question.Consolidation may give these communities the opportunityto address water supply or water infrastructure chal lenges that deter growth or lead to decline.7

Table 1Observed Financial Benefits and Related Case StudiesFinancial BenefitRelated CasesEconomies of scale and efficienciesIowa Regional Utilities Association, page 30City of Raleigh, page 21Hampton Roads Sanitation District, page 25Increased access to lower cost capitalCity of Raleigh, page 21Logan Todd Commission, page 33Town of Colusa, page 18Lower or equal customer ratesCentral Arkansas Water, page 11City of Raleigh, page 21Revenue stabilityCity of Raleigh, page 21New Jersey American Water, page 46Reduced exposure to regulatory penaltiesCitizens Energy, page 14City of Raleigh, page 21Hampton Roads Sanitation District, page 25Improved planning and risk managementCity of Raleigh, page 21Central Arkansas Water, page 11Hampton Roads Sanitation District, page 25Increased opportunities for economic developmentLogan Todd Commission, page 33Key ConsiderationsReal and Perceived Unequal Distribution of BenefitsOne challenge related to consolidating utilities is thatthe financial benefits cannot always be distributed equally.A region may experience aggregate benefits from aless fragmented approach to water management whileindividual communities or utilities may not experience anybenefit. Some may even experience financial loss, andconsolidation is especially difficult in these cases. Eventhough financial savings for the larger region can lookpromising, utility leaders typically make decisions withtheir individual utility or community in mind. Addressinginconsistencies among customers and systems can bechallenging and may require compromise and commitmentto solutions that ensure water services are affordablefor all customers.Decision-makers weighing water utility consolidationcan improve financial outcomes by anticipating roadblocksalong the way. Some of the key financial considerationsto consider include: Up-front costs; Real and perceived unequal distribution of benefits; Savings timeline; Different starting points; and Unequal or conflicting incentives.Up-Front CostsThe initial financial consideration in utility consolidationis the high up-front investment needed to move throughthe consolidation process and establish the consolidatedsystem. Planning, studies, and the staffing capacity toundertake this process can be expensive. In many cases,infrastructure improvements, new projects, or physicalinterconnections between infrastructure assets will alsobe needed.8Savings TimelineCommunities and their utilities can find ways to smoothout or accelerate anticipated net savings or cost avoidance.Smoothing costs means reducing the burden of individualpayments by spreading them out over a longer timeframe.Smoothing net savings means realizing savings insmaller increments over a longer timeframe, often withthe goal of realizing some savings sooner. These canUS Water Alliance

be important considerations when utility decisions aremade by elected leaders whose term limits are shorterthan the time it would take to realize savings. Oftenthese officials hope to show ratepayers real savings orcost avoidance during their term in office. Models andfinancial instruments that can make savings accrue evenlyover time or accelerate savings can encourage theseleaders to support consolidation. Models with high upfront costs may be politically difficult for elected leadersto support, despite long-term savings. Restructuringexisting debt to reduce costs can help in these cases.Different Starting PointsLong-term thinking and analysis are also critical toimproving the chances of consolidation taking place andrealizing financial benefits for the community. Waterutility and government leaders who come together topartner, regionalize, or consolidate often start theprocess from very different financial points. Partners thatbegin the process with very different rate schedules,asset values, savings, and liabilities need to put in effort,account ing prowess, and negotiating finesse to harmo nize agreements.SummaryConsolidation is an important tool for communitiesto consider but is not the right option in all cases. Waterutilities and key stakeholders must assess their optionscarefully. Many positive financial and economic outcomescan accrue from utility consolidation, but communitiesmust also consider and prepare for all the related chal lenges. Communities that have successfully consolidatedutilities have several common characteristics:understanding the financial impacts; patience; long rangeplanning; external incentives; and leadership.Unequal or Conflicting IncentivesCommunities are more likely to see a solution throughif the incentives that need to be in place for consolidationto occur are present and clear. In some instances, ahigher-capacity and financially-healthier utility may seefew incentives to fully consolidate with a lower-capacitysystem and choose a less robust option as a result. Whenthis happens, it can reduce incentives to consolidate inthe future, leaving the additional benefits that opportunitycould have provided unrealized. Identifying regionalbenefits from the outset can help communities with lessincentive better understand why consolidation may beimportant for long-term sustainability.Strengthening Utilities through Consolidation: The Financial Impact9

Part Two:Financial Case StudiesCommunities considering utility consolidation can learnfrom those who have already gone through the process.This section of the report provides eight case studies ofcommunities that have consolidated or regionalized waterservice. Taken together, the case studies illustrate thediverse drivers, agreements, institutional arrangements,and outcomes associated with water utility consolidation.11 Central Arkansas Water Two municipal water departments consolidate to providean affordable and reliable water source for the futureThese case studies are not comprehensive analyses ofutility consolidation. Rather, they focus on the financialdynamics. There are many important and complex social,environmental, and political aspects involved in eachcase not addressed in this report. For example, while longterm rate savings for customers are discussed in thefollowing case studies, the community response andexperiences during the consolidation process are notcovered. Though each case includes some informationas background, the politics, governance decisions,and legal processes and agreements deserve furtherresearch and assessment. Nevertheless, these casesprovide important information on key considerations andfinancial impacts. This is a necessary first step to buildunderstanding about consolidation options and benefits.18 City of Colusa Small privately-owned water district consolidates withcity to address contaminated drinking water supplies14 Citizens Energy Group Energy, water, and wastewater systems consolidate tostreamline service and reduce rates21 City of Raleigh Public Utilities Department Seven local utilities merge into a full-service regionalwater and wastewater provider25 Hampton Roads Sanitation District Regional wet weather program saves money, protectsChesapeake Bay30 Iowa Regional Utilities Association Rural water systems consolidate to provide reliable,higher quality water supply33 Logan Todd Regional Water Commission Twelve systems create treatment facility to provide areliable regional water supply and drive economicdevelopment36 New Jersey American Water Borough-owned water systems consolidate withstatewide investor-owned utility to tackle needed,costly capital improvements10US Water Alliance

Financial Case StudyCentral Arkansas WaterTwo municipal water departments consolidate to provide an affordable and reliable watersource for the futureDate of established agreement 2001: Signed Consolidation Agreement merging Little Rock and North Little Rock waterdepartments to establish Central Arkansas Water (CAW)Services involvedOwnership, management, and provision of drinking water assets, services, and supply in 2011 andwastewater services authorization granted in 2017Governance modelTwo municipal utilities merging to form a single larger publicly owned utility governed by a sevenmember board of commissionersCommunities involved2001: City of Little Rock City of North Little RockAdditionally: Brushy Island Public Water Authority 145th Street Water and Sewer Improvement District Wye Mountain Public Water Authority Maumelle Water ManagementCAW also provides retail water to City of Sherwood and wholesale water to more communities.Population served450,000 people over a 360-square mile service areaSystem capacity/demands3,000 metered service connections with the capacity to provide approximately 157 million gallonsof potable water per day and an average daily demand of 62 million gallonsExternal policy drivers andincentivesA study by University of Arkansas at Little Rock (2000) commissioned by both cities recommendedconsolidationFinancial and economicimpacts Rate equalization and stabilization Increased efficiency and reduction in duplication related to water supply investment needs The ability to borrow greater amounts of money due to the larger customer base and highercredit ratingsRevenue flowsCustomers from multiple communities pay uniform fees directly to the consolidated utilitySummaryFor systems facing regional water supply challenges, the creation of Central Arkansas Water (CAW) exemplifies the potentialfor consolidation to result in positive financial impacts for the utility and community. It helped stabilize rates and eliminated ratedifferences between residents of a large region of central Arkansas. Moving from a water supplier and purchaser wholesalerelationship, two municipal water systems in North Little Rock and Little Rock fully merged to create a single consolidated waterutility. The consolidated CAW shares water supply costs across the two jurisdictions, generates efficiency by combining distributionsystem maintenance and customer service functions, equally distributes rates, and borrows capital at a lower cost to invest ininfrastructure or supply needs. Since it was created, other smaller utilities have joined CAW.ContextIn 1936, the Arkansaw Water Works Company, a private utility, provided drinking water to both Little Rock and North Little RockAt the time, the region needed a reliable, cleaner water source than the Arkansas River, and the City of Little Rock sought a PublicWorks Administration grant to build a reservoir. To be eligible to receive the public grant funds to improve their citizen’s waterStrengthening Utilities through Consolidation: The Financial Impact11

service, Little Rock had to purchase the Arkansaw Water Works Company’s facilities south of the Arkansas River and create apublic utility. As part of the agreement to purchase those assets, Little Rock agreed to continue to provide water to Arkansaw WaterWorks Company for several customers north of the river. One of those customers was North Little Rock, which subsequentlypurchased the Arkansaw Water Works Company’s facilities north of the Arkansas River creating their own public water utility in1959, though they still purchased water from Little Rock.The arrangement provided some benefits but also led to continuous conflicts that lasted until their comprehensive consolidation.The two entities’ unique historic relationship, having been joint customers of Arkansas Water Works Company and then havingbecome two separate systems, created multiple challenges in maintaining a stable relationship. The regional arrangement prior toconsolidation was mandatory but also rife with conflict. Conflicts primarily emerged over rates and the need for a long-termcontract. North Little Rock wanted to be charged the same rates Little Rock was charging Arkansaw Water Works Company, whichthe Arkansas Supreme Court decided were no longer adequate. However, in the same opinion, the Court established that LittleRock could not cede its obligation to provide water to North Little Rock because of the process it agreed to when it created itsmunicipal system. There were further disputes over capacity and North Little Rock’s inability to expand its service area because ofthe demands it would place on Little Rock as the provider.Tensions over rate increases, rate differentials, difficulties in agreeing to a formal long-term contract arrangement, and concernsabout future regional water supply increased, and the two municipal entities reached a standstill in 1999. That year, the City of LittleRock hired Black & Veatch to do a rate and revenue study to assess the city’s utility needs and rate structure. The findings showedinequity in the current rates and that master-metered wholesale customers, such as North Little Rock, were paying less than the truecost of their water. Black & Veatch recommended Little Rock establish a cost of service rate structure, requiring significant rateadjustments for each customer class. The Little Rock Water Commission adopted the recommendations despite the objections ofwater purchasers, including North Little Rock.North Little Rock was given the choi

data, and information to support informed decision making. Towards that end, the US Water Alliance and the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina developed this report focused on the financial outcomes utilities have realized through consolidation. This report focuses on the impacts of different consolidation