Transcription

European Journal of Law and Economics, 4:41–54 (1997) 1996 Kluwer Academic PublishersDecision Costs, Contract Excuse, and theWestinghouse Commercial Impracticability CaseDONALD VANDEGRIFTSchool of Business, Trenton State College, Hillwood Lakes, CN4700, Trenton, NJ 08650-4700, e-mail: vandedon@trenton.eduAbstractThe literature on performance excuses does not consider the cost of determining whether the conditions established for contract excuse are met. We must incorporate these costs to determine which contract laws are efficient. I show that while the costs of determining whether the conditions for excuse are met will rise with the valueof the contested performance, the benefits are unrelated to the value of performance. I conclude that the courtshould not allow excuse if the value of the contested performance is large.Keywords: contact excuse, DUP, impossibility, commercial impracticability1. IntroductionIn a seminal paper, Tullock (1967) showed that traditional models of monopoly had underestimated the efficiency costs associated with monopoly. According to Tullock, a broadclass of governmental barriers lead to directly unproductive profit seeking (DUP),1 andthus the standard allocative efficiency triangle captures only a fraction of the efficiencycost of monopoly. Like the pre-Tullock monopoly literature, the literature on contractexcuse fails to incorporate the costs of DUP.Previous work on contract excuse (Posner and Rosenfield, 1977; Perloff 1981; Bruce,1982; Goldberg, 1988; White, 1988; Sykes, 1990; Trimarchi, 1991) has focused on thebenefits of contract excuse (for example, more efficient risk allocation). In so doing, itconsiders the conditions under which the court should excuse performance to improvewelfare or maximize the joint value of the contract. But the existing rules for contractexcuse, as well as those proposed in the literature, require that courts make decisionsbased on factors that they cannot directly observe. Thus, the literature ignores the extraordinary incentives created for costly litigation in a world in which facts are unclear, andcourts must draw inferences from these facts.2 Rather than considering the conditionsunder which court excuse would improve welfare, courts should consider whether thesocial benefits of allowing excuse under the proposed conditions exceed the costs of determining whether the conditions established for excuse are met.If courts can determine costlessly and without error whether the conditions for excuseare met, contractors have no incentive to use performance excuses strategically. But if thepotential for court error exists, there is a real danger that contractors will use performance

42VANDEGRIFTexcuses strategically. Under the doctrines of commercial impracticability and frustrationof purpose, courts condition excuse on nonobservable factors like “foreseeability.”Deciding cases based on nonobservable factors increases court costs. In addition, nonobservable factors increase the probability of court error. Errors increase because the inquiryis complex and because agents have an incentive to distort information or disclose it selectively.I will argue that as the value of the contested performance3 increases, the probabilitythat the net benefits of commercial impracticability and frustration of purpose are negative also increases. This occurs for two reasons. First, the cost of determining whether theconditions for excuse are met rises with the value of performance. Economic agents willspend more on litigation as the amount contested at trial rises. If a claim for excuse yieldsexpected profits, the contractor will spend any dollar on litigation that yields an expectedpayoff greater than that dollar. Even if defendants expected that courts will not releasethem from their obligations, these performance excuses provide a mechanism for defendants to redistribute the gains to a contract. Under threat of a long and drawn-out courtbattle, plaintiffs may agree to a redistribution.Second, the social benefits of contract excuse are unrelated to the value of performance.4 Maximizing the joint contract value (that is, social benefits) requires that courtschoose contract clauses that the parties would have chosen at contract initiation (Posnerand Rosenfield, 1977; Perloff, 1981; Bruce, 1982; Goldberg, 1988; White, 1988; Sykes,1990). But at contract initiation, the parties have an incentive to include in the contractclauses that have high expected benefits. Any contract clauses that the courts infer ex postmust necessarily have low expected benefits. If a commercial contract dispute involves acontested performance with a large market value, the cost of determining whether the conditions are met will exceed the social benefits of contract excuse. Courts should, therefore,not permit excuse under commercial impracticality, frustration of purpose, or any of therules proposed in the literature that condition excuse on nonobservable factors if the valueof the contested performance is large.To further demonstrate the high costs of determining whether the conditions for excuseunder the commercial impracticability and the frustration-of-purpose defenses are met, Iexamine the Westinghouse commercial impracticability case (Westinghouse cited commercial impracticability and refused to perform on uranium supply contracts after the market price of uranium tripled). Because of the extensive third-party reports of the eventsleading up to the trials and the negotiations both inside and outside the courtroom, theWestinghouse case is useful to point out the strategic aims that the commercial impracticability defense may serve. While the Westinghouse case was large, the mechanics of thelegal maneuvering are likely to be the same for smaller cases.I divide the discussion into three sections. First, I survey the literature on contractexcuse and argue that it does not consider the cost of determining whether the conditionsfor excuse are met. Second, I construct a simple model to consider the benefits and costsof contract excuse. In the final section, I use the Westinghouse commercial impracticability case to support several of the propositions put forth in the preceding sections and establish a number of additional points. First, private-party negotiations are faster and moreeffective than court ordering.5 The possibility of a court-imposed solution often slows

DECISION COSTS, CONTRACT EXCUSE, AND IMPRACTICABILITY43down the negotiation process. Second, the promisee rarely has an incentive to drive thepromisor into bankruptcy.6 Finally, current performance excuses may cause the promisorto wait to communicate the severity of the situation.72. Contract excuse and the impossibility literatureEconomic analyses of the impossibility-related defenses generally do not consider thecosts of determining whether the conditions for excuse are met. Thus, the analyses includeonly the possible benefits of excuse.When the court decides a performance excuse case, it decides whether to reallocate theburden of a contingency that has increased the cost of performance to the promisor ordecreased the benefits to the promisee. For instance, the court allocates the burden of thecontingency to the promisee when it excuses a promisor from performing on a contract.Posner and Rosenfield (1977) argue that excuse should be allowed when the promisee isthe superior risk bearer.If the promisor is the superior risk bearer, nonperformance should be treated as breach.A promisor may be the superior risk bearer and thus be held to his promise for two reasons.First, the promisor might be better able to prevent the risk from materializing. Posner andRosenfield (1977) contend that excuse “would be inefficient in any case where the promisorcould avoid the risk at lower cost than the expected cost of the risky event” (p. 90). Second,the promisor might be the superior insurer. Consequently, even though the promisor couldnot at reasonable cost have prevented the event, she still may be held to her promise. Bothrisk appraisal costs and transactions costs determine which party is the cheaper insurer fora particular event. Risk appraisal costs comprise the cost of determining the probability thatthe risk will materialize and of measuring the magnitude of the prospective loss.It is not possible to observe easily which party is the superior risk bearer in Posner andRosenfield’s framework. One must infer a conclusion from economic evidence that isoften less than clear cut. Posner and Rosenfield (1977) admit, “When the two key parameters of the economic analysis point in opposite directions, the analysis is indeterminateon a general level and must proceed to estimation of their relative empirical importance”(p. 102). The authors also exhibit some sensitivity for the cost of such an undertaking (p.103):But there is a question whether so microscopic an examination of the facts is an appropriate predicate for decision, in light of the administrative costs, discussed in Part I, ofapplying the impossibility doctrine on a highly particularistic case-by-case basis ratherthan on the basis of rules that decide all of the cases within a specific category in thesame way—for example, a rule deciding all lease discharge cases either in the lessee’sor in the lessor’s favor. Unfortunately, it is unclear, a priori, which would be the moreefficient rule.Although Posner and Rosenfield realize there are administrative costs involved, theyattempt no discussion of DUP that would occur under such a proposal.

44VANDEGRIFTSeveral other papers follow the Posner and Rosenfield risk aversion framework. Eachconcentrates only the benefits of excuse and ignores the costs (DUP). Perloff (1981) considers excuse in a model of a forward market. Bruce (1982) refines the original frameworkto consider the effect of informational imperfections on the optimal allocation of liabilityand the decision to mitigate damages. Like Posner and Rosenfield, White (1988) arguesthat the critical consideration is risk aversion. However, White considers all unperformedcontracts as breach of contract cases. The argument requires that courts perform a two-stepprocess. First, courts must determine the expectation damages. Second, the courts mustconsider reducing damages based on relative risk aversion. Efficient damage remedies aresmallest when the performing party is risk averse and the nonperforming party is risk neutral. Negative and zero damages (discharge) occur in rare instances. Sykes (1990) followsWhite by also incorporating breach of contract into the analysis.While Goldberg (1988) also fails to consider the costs of excuse, he proposes a basis forexcuse that is unrelated to relative risk aversion. Goldberg weighs the costs of holdingpromisors to agreements with the costs of releasing them. If the costs of holding apromisor to an agreement exceed the cost of release, the court should excuse performance.The costs of holding a promisor to an agreement result from the cost of monitoring thereasonableness of the promisee’s demands for substitute performance (that is, moral hazard costs). Because of full insurance, the promisee has no incentive to choose the mostefficient substitute.But in order for substitute performance to cause a moral hazard problem, the promisormust be physically unable to perform. Otherwise, the court does not need to judge the reasonableness of substitute performance. Thus, moral hazard costs are not incurred if performance is simply commercially impracticable or if the purpose of the agreement is frustrated.3. The costs and benefits of contract excuse3.1. The costs of performance excuseIf courts use discretion to decide cases, the costs of deciding performance excuse caseswill vary directly with the value of the contested performance. Under the current commercial impracticability and frustration of purpose rules, courts use discretion because therules condition excuse based on nonobservable factors (such as foreseeability). Forinstance, commercial impracticability under the Uniform Commercial Code allows excuseif “performance as agreed has become impracticable by the occurrence of a contingency,the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made.”8But the court must not only make a discretionary decision about what is impracticable, itmust also make other discretionary decisions about foreseeability and indirect assumptionof risk.9Similarly, courts must make a discretionary decision under the doctrine of frustration ofpurpose and the proposed doctrines based on relative risk characteristics in the impossibility literature (Posner and Rosenfield, 1977; Perloff, 1981; Bruce, 1982; White, 1988; Sykes,

DECISION COSTS, CONTRACT EXCUSE, AND IMPRACTICABILITY451990). A contractor may plead frustration of purpose if an implied condition of the agreement does not occur or ceases to exist without the fault of either party and the absence ofthe implied condition “frustrates” one party’s intentions in agreeing to the contract.10Implied conditions and “frustrated” intentions are by their very nature debatable. Under theproposed doctrines, a promisor may gain excuse if the court decides that the promisee is thesuperior risk bearer. But as Posner and Rosenfield (1977) concede, excuse under such a rulerequires that judges use discretion to infer a conclusion from economic evidence.In deciding a case for excuse, the court essentially awards a sum equal to the value ofperformance—the difference between the market price and the contract price. Because thecourt uses discretion under all of the above legal rules, the contractors will spend resourcesto influence the outcome. Tullock (1967) notes that producers will invest resources in lobbying for a tariff until the expected marginal benefit on the last dollar spent lobbying isequal to the marginal costs. The lobbying expenditures are pure social waste and the magnitude of the waste is directly related to the expected gains from the tariff.Awarding a tariff is analytically the same as awarding either release from the obligationto perform or the right to force performance. Accordingly, the costs of determiningwhether the conditions established for excuse are met will be directly related to the valueof performance. That is, the contractors will consume real resources in an attempt to gainthe rents. We can expect that contractors will spend each dollar that increases expectedreturns more than that dollar. Contractors will always spend each additional dollar in a waythat maximizes their probability of prevailing at trial. This requires that they first completethe tasks that have the greatest positive effect on their probability of winning. An increasein the stakes implies that additional tasks will have expected returns that are greater thantheir costs. Thus, the amount of resources consumed in the attempt to gain the rents is adirect function of the value of performance.11Although there is no way to tell precisely what this function may look like, a significantportion of the stakes will be dissipated in legal maneuvering. Tullock (1980) shows thatunder certain behavioral assumptions the directly unproductive profit-seeking (DUP)expenditures may exceed the rents at stake. Moreover, the structure of the institutions alsopoints to excessive DUP expenditures. Congleton (1980) shows that rules providing forall-or-nothing payoffs will promote more social waste than rules that reward each agentproportionally.Because the value of performance essentially determines the cost of reallocating theburden of the contingency, models that assume a constant value of performance are fundamentally flawed. A rational contractor will not spend valuable resources on litigation toprotect a right that has no market value. For instance, a contract may specify that apromisor must supply good A at 10 per unit. If a contingency occurs that drasticallyincreases the promisor’s cost of performance, the promisee will not litigate if substituteperformance is available for 10 per unit of good A. Yet both White (1988) and Sykes(1990) assume that the contingency does not change the value of performance. Cases inwhich the value of performance does not rise along with costs of performance typically donot reach trial. Interestingly, the cases that Sykes reviews confirm this (Sykes, 1990, pp.73–90). In each of the decisions he examines, the value of performance rises right alongwith the cost of performance.

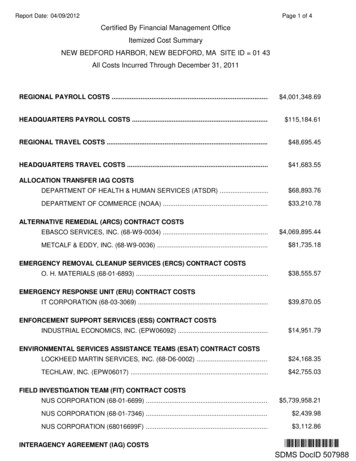

46VANDEGRIFT3.2. The benefits of performance excuseThe contract with the highest social value uses the best information ex ante to allocaterights and responsibilities under the contract for the appropriate price (Posner andRosenfield, 1977; Goldberg, 1988; Sykes, 1990).12 Suppose, for instance, that promisorsmust bear the risk for all possible contingencies. Promisees may, in turn, agree to bear therisk for certain contingencies in return for a lower contract price. Thus, the parties will addclauses that allocate the risk toward the promisee in return for a lower price if the promiseecan self-insure or obtain insurance at rates lower than the price reduction.If a contingency occurs and the contract does not explicitly specify the parties’ obligations for such a contingency, a party to the contract may seek excuse. The court’s ex postintervention is valuable if it affects the ex ante expectations of the parties. Knowledge thatthe court will intervene to correctly allocate the burden of the contingency ex post willincrease contract values ex ante. Accordingly, any benefits from reallocating the burden ofthe contingency must exist at contract initiation. To maximize the joint value of the contract, the courts must consider the way in which the parties would have allocated the costof the contingency at contract initiation (Posner and Rosenfield, 1977; Perloff, 1981;Bruce, 1982; Goldberg, 1988; White, 1988; Sykes, 1990). I will show that these benefitsdepend on a number of factors, none of which are related to the value of performance.To consider the benefits of contract clauses, we must examine the reasons that contracting parties may fail to include a particular clause in a contract. A contract may fail tospecify the obligations of the parties for four reasons: (1) both contractors judged the probability of the event to be so small that it did not warrant the cost of negotiating a clausespecifying obligations; (2) the contractors failed to even consider the possibility of such acontingency; (3) one of the contractors was aware of the possibility of a certain contingency but did not alert the other party; and (4) to specify such a clause would expose oneof the parties to strategic-behavior risk.13But the benefits to the court’s ex post intervention are likely to be small. More important, the benefits will not vary with the value of performance. In the first case, the contractors do not negotiate a clause covering the contingency because of the cost. Courtintervention provides benefits if courts supply the terms (ex post) that the parties foundtoo costly to negotiate. But these benefits are not related to the value of performance. Atcontract initiation, the contractors will add terms until the expected benefit of an additional term equals the cost of negotiating an additional term.Figure 1 shows a marginal benefit (MB0) schedule that arranges possible contractualclauses from highest to lowest expected benefit. The expected benefits of additional clauses depend on the probability that the contingency will occur, the cost of the contingencywhen it does occur, and the differential ability of the parties to bear risk. In large commercial contracts, contingencies are often more costly and the marginal expected benefitsof the individual contractual clauses rise (MB1). But changes in the value of the contractand the cost of a contingency do not change the cost of negotiating additional clauses(MC). The marginal cost of adding terms will depend largely on the opportunity cost ofthe lawyer’s time. Because the expected benefits of the last clause always equal the marginal cost, contracts that involve higher stakes will contain more contractual clauses,

DECISION COSTS, CONTRACT EXCUSE, AND IMPRACTICABILITY47Figure 1.ceteris parabus (Y1 Y0). However, the expected benefit of the last clause added will bethe same across agreements. Therefore, we can expect that (1) the expected benefits ofindividual clauses that do not appear in the agreement must be less than the marginal costof the lawyer’s time; and (2) the expected benefits of court intervention are independentof the value of performance.In the second case, the contractors fail to even consider the possibility of the contingency. If the contractors do not consider the possibility of the contingency, the estimatesof the value of the contract are completely unaffected by the court intervention. If theevent is truly unforeseeable, the functions of insurance and risk bearing break down.Trimarchi (1991) argues that extraordinary and unforeseeable events that affect large sections of society do not allow the principle of insurance to operate. Assigning the risk ofthese events will not in any way affect the probability that the event occurs. Placing therisk of the contingency on the “superior insurer” will not affect ex ante contract valueseither. The principle of insurance requires the contractor to aggregate a number of homogeneous and uncorrelated risks. In order to reduce overall risk, the individual risks mustexhibit a statistical regularity. Otherwise, losses in a given timespan are not predictablewith a reasonable degree of accuracy. We can therefore expect that there will be no gainsto reallocating the burden of a contingency.14In the third case, a contractor with superior information takes advantage of the otherparty. Here, the possibility of excuse will be ineffective as a means to force betterinformed parties to reveal what they know. For instance, a buyer with superior information

48VANDEGRIFTabout risks may conceal the information to receive a lower contract price.15 Buyers andsellers may complete exchanges for which there are no net benefits. A performance excusecould, in theory, alleviate this problem. The threat of releasing sellers from their obligationwhen buyers conceal risks would force buyers to reveal their knowledge about possiblerisks. However, such a threat will be ineffective. Better-informed buyers will react to thethreat by simply specifying a clause in the contract that explicitly allocates the risk of thecontingency to the seller.Finally, the parties may fail to specify a clause because it exposes one of them to strategic-behavior risk. Court intervention to specify such a clause can provide no benefits andmay entail substantial costs. If courts read such clauses into agreements, they expose oneor both of the contractors to the strategic-behavior risk they originally sought to avoid. Theexposure will decrease the value of the contract.In sum, the cost of determining whether the conditions are met rises monotonically withthe value of performance. The court, in deciding a case for excuse, gives away a valuableright. The litigants will spend more as the value of that right increases. In contrast, the benefits of court intervention are unrelated to the value of performance. The benefits of courtintervention to allocate the burden of a contingency (excuse performance) may be characterized as a random variable that is uncorrelated with the value of performance and withan upper bound of the opportunity cost of the lawyers’ time to write the particular clauseto allocate the burden.As the value of performance increases, the case for allowing performance excusebecomes weaker. An increase in the value of performance increases the probability that thecosts of court intervention (determining whether the conditions for excuse are met) exceedthe expected benefits of court intervention (supplying the appropriate clause). If the valueof the contested performance is large, courts should not permit excuse under commercialimpracticability, frustration of purpose or any of the rules proposed in the literature whichcondition excuse on nonobservable factors. Thus, the strongest case for allowing excuseoccurs when (1) the value of the contested performance is small, (2) the parties to the contract could have contemplated the possibility of the contingency, and (3) they did not allocate the burden of the contingency because of the costs of negotiation.4. Analysis of the Westinghouse commercial impracticability caseThe facts of the Westinghouse case are available elsewhere, and I will not repeat them here(Joskow, 1977; Yokell and DeSalvo, 1985; Vandegrift, 1993). I do, however, wish to highlight several aspects of the case that pertain to my argument. First, the commercial impracticability defense caused high expenditures but few if any benefits. Second, performanceexcuses are an inefficient tool to force contractors to mitigate damages. Third, the possibility of bankruptcy even in the absence of performance excuse is slim.The DUP expenditures in the Westinghouse case were the result of the enormous stakescreated by the possibility of excusing performance on contracts for supply of about 2 billion worth of uranium and the uncertainty associated with legal rules that rely on nonobservable factors. It is impossible to determine the exact amount of DUP expenditures

DECISION COSTS, CONTRACT EXCUSE, AND IMPRACTICABILITY49caused by the possibility of excuse under the commercial impracticability defense.Adjusting to the shock of higher uranium prices clearly requires renegotiation of contractual terms. Renegotiation is costly. Thus, the contractors may incur adjustment costs underany legal regime. An honest measure of the costs of court intervention must include onlythe costs over and above the adjustment costs in the absence of court intervention.Despite the measurement difficulties, there is clear evidence that the costs of court intervention are substantial and that the costs increase with the value of performance. Courtintervention is costly for two reasons. First, the possibility of a court-imposed solutionoften slows the negotiation process. Negotiations between the disputants would have proceeded at a faster pace if the allocation of rights and responsibilities were certain.Uncertainty about how the court would decide, therefore, made bargaining more difficult.Second, the possibility of excuse caused Westinghouse and the utilities to collect, process,and present information that would be useless in private-party negotiations.Although a performance excuse as ill-defined as commercial impracticability does notdecrease uncertainty, the courts often made the situation worse. For instance, in the wakeof the settlements reached in the Pennsylvania trial, the judge made comments that seemedto suggest Westinghouse might be excused from performing the contracts in the upcoming trial in Richmond federal court. “Westinghouse introduced extremely persuasive competent evidence [that] a number of interrelated contingencies rendered performance ofthe asserted contracts commercially impracticable” (Wall Street Journal, 1977a). But thejudge countered that “Westinghouse owed [the utilities] a continuing fiduciary obligationto insure” (Wall Street Journal, 1977a). Such statements would explain at least in part whythere was not another settlement until the federal trial began in Richmond six months later.The judge in the federal case made similar errors. He declared during the proceedings that“nobody has a locked case on this litigation” (Wall Street Journal, 1977c).The commercial-impracticability defense provided incentives for public posturing thatwere costly and did little to help the private negotiations. The Texas Utilities Services Inc.(TUSI) settlement is instructive in this regard. When the settlement negotiations betweenWestinghouse and TUSI finally commenced, the atmosphere was workmanlike and constructive, (Wall Street Journal, 1977b). But as the companies quietly negotiated, the public pronouncements of Westinghouse remained strident. Westinghouse continued to insistpublicly that the court should excuse performance. Public efforts to portray the consequences of the uranium cartel and the uranium enrichment policies of the AEC as unforeseen persisted.In light of the uncertain legal regime, the economic rationale for such maneuvers isclear. The efforts represent an attempt not only to influence the court but also to influencethe expectations of the other party. Sometimes, of course, the efforts backfire, and the disputants move further apart. Individual pieces of evidence may be interpreted differently.Westinghouse spent large sums gathering evidence on an international uranium cartel.Westinghouse gathered the information not only to strengthen its case for excuse but tochange the expectations of the utilities. To the degree that Westinghouse was successful,the utilities settled for less.Information acquisition went far beyond anything necessary for private negotiations.Perhaps the largest expenditure was the Westinghouse antitrust suit against uranium pro-

50VANDEGRIFTducers. In 1976, Westinghouse virtually ignored the possibility of settling cases, as thecompany concentrated almost completely on compiling information on the internationaluranium cartel to strengthen its case for excuse. (Wall Street Journal, 1978). It was nosecret that Westinghouse hoped the price-fixing charges would strengthen its case forexcuse (Wall Street Journal, 1979). The utilities, on the other hand, investigated whatWestinghouse knew about the shortage of uranium and when they knew it (Wall StreetJournal, 1978).Damages that result from a failure to perform may be reduced by the actions of the contractors. Efficiency requires that the contractors take any actions that cost less that themarginal reduction in damag

School of Business, Trenton State College, Hillwood Lakes, CN4700, Trenton, NJ 08650-4700, e-mail: vande-don@trenton.edu . Negative and zero damages (discharge) occur in rare instances. Sykes (1990) follows White by also incorporating breach of contract into the analysis. While Goldber g (1988) also f ails to consider the costs of e xcuse, he .