Transcription

Number 383 March 12, 2007Table 2 has been revised (May 2007).Office-based Medical Practices: Methods andEstimates from the National AmbulatoryMedical Care Surveyby Esther Hing, M.P.H., and Catharine W. Burt, Ed.D., Division of Health Care StatisticsAbstractIntroductionObjectives—The report uses a multiplicity estimator from a sample of officebased physicians to estimate the number and characteristics of medical practices inthe United States. Practice estimates are presented by characteristics of the practice(solo or group, single, or multi-specialty group, size of practice, ownership,location, number of managed care contracts, use of electronic medical records, anduse of computerized physician order entry systems).Methods—Data presented in this report were collected during physicianinduction interviews for the 2003–04 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey(NAMCS). The NAMCS is a national probability sample survey of nonfederalphysicians who see patients in an office setting in the United States. Radiologists,anesthesiologists, and pathologists—as well as physicians who treat patients solelyin hospital, institutional, or occupational settings—are excluded. Sample weights forphysician data use information on the number of physicians in the sampledphysician’s practice to produce annual national estimates of medical practices.Results—During 2003–04, an average of 311,200 office-based physicianspracticed in an estimated 161,200 medical practices in the United States. Medicalpractice characteristics differed from physician characteristics. Although 35.8 percentof office-based physicians were in solo practice, 69.2 percent of medical practicesconsisted of solo practitioners. The one-fifth of medical practices with three or morephysicians (19.5 percent) contains about one-half of all office-based physicians(52.4 percent). About 8.4 percent of medical practices involved multiple specialties.Fifteen percent of medical practices, consisting of 19.0 percent of physicians, usedelectronic medical records. Similarly, 6.5 percent of medical practices, consisting of9.2 percent of physicians, used computerized prescription order entry systems.In the United States, physicianoffices are the most frequent locationwhere patients receive care (1). Aprevious report (2) presented estimatesof physicians practicing in the UnitedStates based on data collected during theinduction interview of the 2003–04National Ambulatory Medical CareSurvey (NAMCS). Decisions affectingpatient care services, such as adoptionof evidence-based guidelines or use ofelectronic medical records, however,may be made at the organizational levelof the medical practice, rather than byindividual physicians. This report,therefore, augments the previous reportby presenting estimates for medicalpractices derived from the same data. Tomake practices rather than physiciansthe unit of analysis, it is necessary toadjust the weighting scheme through theuse of a multiplicity estimator. Althoughusing a multiplicity estimator is not new(3–6), the methodology has never beenapplied to deriving practice estimatesfrom NAMCS physician data. Adjustingthe physician weight by the number ofphysicians in the practice has themathematical effect of yielding only oneobservation from each medical practice;the sum of the adjusted weights yields aKeywords: ambulatory care c physician medical practice c NAMCSU.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICESCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Health Statistics

2Advance Data No. 383 March 12, 2007national estimate of the number ofmedical practices. Practice estimates inthis report describe medical practicecharacteristics and decisions made bythe practice that may affect patient care,such as use of electronic medical recordsystems.The NAMCS is a nationallyrepresentative survey of visits tononfederally employed, office-basedphysicians conducted by the NationalCenter for Health Statistics (NCHS).The NAMCS is part of the ambulatorycare component of the National HealthCare Survey, a family of provider-basedsurveys that measures health careutilization across various types ofsettings. More information about theNational Health Care Survey can befound at the NCHS Internet address:www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhcs.htm.MethodsThe NAMCS is an annual nationalprobability sample survey of physiciansclassified by the American MedicalAssociation (AMA) and the AmericanOsteopathic Association (AOA) asprimarily engaged in ‘‘office-based,patient care.’’ Federally employedphysicians; those who specialize inanesthesiology, radiology, or pathology;and physicians who do not see patientsin an office, such as the majority ofemergency medicine physicians, areexcluded. The NAMCS utilizes amultistage probability sample designinvolving samples of 112 geographicprimary sampling units (PSUs),physicians stratified by specialty andsampled within PSUs, and patient visitssampled within physician practices. ThePSUs are counties; groups of counties;county equivalents, such as parishes orindependent cities; or towns andtownships, for some PSUs in NewEngland.In the 2003–04 NAMCS, 6,000physicians were sampled. During theinduction interview, physicians wereasked questions to determine theireligibility for the survey, and to gatherinformation about their practice such assize, ownership, and revenue sources. Of3,968 physicians eligible for the survey,2,235 physicians who saw patientsduring their sampled weeks respondedto the Physician Induction Interview(PII), for an unweighted response rate of56.3 percent.Both the physician and office visitestimation procedures have three basiccomponents:1. Inflation by reciprocals of thesampling selection probabilities2. Adjustment for physiciannonresponse, and3. A calibration ratio adjustmentbetween the number of physicians inthe sample frame when the samplewas selected and the number ofphysicians when the NAMCS datawere collected.For each physician, the samplingselection probability reflects theprobability of PSU selection andselection of physicians within each PSU.The physician nonresponse adjustmentfactor is the sample weight forresponding physicians augmented by afactor accounting for the amount ofnonresponse by similar physicians.Similar physicians were judged to bephysicians having the same specialtydesignation and practicing in the samePSU and/or region/metropolitanstatistical area (MSA) status. Thecalibration ratio adjusts the number ofphysicians based on the sample framewithin specialty stratum and region cellsto reflect the most recent universecounts provided by AMA and AOA forthe NAMCS weights. For example, theestimated number of physicians in 2003increased from 280,500 to 312,400 aftercalibration ratios were applied.Similarly, the estimated number ofphysicians in 2004 increased from282,100 to 309,900 after application ofthe calibration ratios. A previous reportpresents information on physicianestimation, response rates, and surveydefinitions in more detail (1).The sample weights for office visitsinclude the same physician nonresponseadjustment and calibration ratiocomponents utilized in the physicianweight. The major difference betweenthe physician and visit weight is in thesampling probabilities for visits. That is,the visit sample selection probabilitiesreflect selection of PSUs, selection ofphysicians within each PSU, as well asselection of visits within eachphysician’s practice. In addition, thevisit weights go through a smoothingprocess such that excessively large visitweights are truncated and a ratioadjustment is performed. This techniquepreserves the total estimated visit countwithin each specialty by shifting the‘‘excess’’ from visits with the largestweights to visits with smaller weights.More details on the NAMCS samplingdesign and estimation process have beenpublished (7,8).Medical practice estimatesIn this report, the NAMCSphysician sampling weight is modifiedto produce a medical practice estimator.Multiplicity occurs within a samplingframe when a member of the populationis linked to more than one entry on theframe, so that the member has multiplechances of being selected. In theNAMCS sampling frame, multiplicityexists among partnerships and grouppractices because medical practices withmore physicians have a higherprobability of being selected thanpractices with fewer physicians. Grouppractices are defined as three or morephysicians practicing together with acommon billing and medical recordsystem (9). No sampling frame currentlyexists for sampling all types of medicalpractices, i.e., solo, partnership, andgroup. Sampling frames for individualphysicians and for group practices exist,but no sampling frame has all practices.Modifying a physician survey to makeestimates of medical practices has theadvantage of using a single survey andarithmetic manipulations to estimateboth physicians and practices. In thisreport, nationally representativeestimates of medical practices werederived using a ‘‘multiplicity estimator’’to account for multiplicity in thephysician frame (4).The multiplicity measure used inthis calculation was based on physicianresponse to the question ‘‘How manyother physicians are associated with you(at this location)?’’ This question wasasked for a maximum of four officelocations at which the sample physiciansaw ambulatory patients during his/hersampled week (see Excerpts from the2004 Physician Induction Interview (PII)

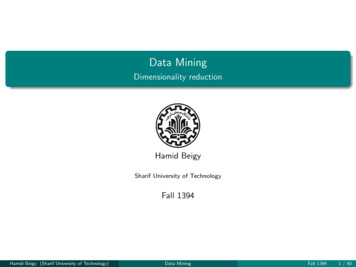

Advance Data No. 383 March 12, 2007form in ‘‘Technical Notes,’’ Figure I).Practice size was assumed to be oneplus the number of other physiciansrecorded at the first-listed location.About 14.4 percent of physiciansreported that they saw patients atmultiple office locations. Medicalpractices were estimated by adjustingthe physician sample weight by theinverse of the multiplicity indicator(number of physicians in the practice) toaccount for the increased likelihood ofselection:(Medical practice weight)ij (Physiciansample weight)ij/Sij,Where Sij number of physicianswithin practice j reported by physician i(52.4 percent). The percentage ofpractices that are multi-specialty groups(8.4 percent) is smaller than thepercentage of physicians in thesepractices (21.1 percent), although thepercentage of practices that are in soloand single specialty groups(91.6 percent) is larger than comparablepercentage of physicians in thesepractices (78.9 percent). The percentageof health maintenance organization(HMO) practices is only 0.5 percent, butthe percentage of physicians in HMOpractices is 2.0 percent.As would be expected, the percentdistribution of office visits by practicesize more closely resembles thedistribution of physicians than it doesmedical practices. Practices involving 11or more physicians constituted only1.2 percent of practices, but 9.8 percentof all visits occurred at these practices,since 10.7 percent of all physicians areemployed there. In contrast, solophysician practitioners, who constituted69.2 percent of all practices but35.8 percent of all physicians, had36.8 percent of all office-based visits.Similarly, solo and single-specialtypractices and multi-specialty grouppractices constituted 91.6 and8.4 percent of all practices, respectively,using SUDAAN were performed todetect significant associations amongpractice characteristics. Tests of lineartrends, such as the percent of revenuefrom managed care contracts by size ofpractice, are based on a weighted linearregression with significance at the 0.05level. All other tests of statisticalsignificance among estimates are basedon the two-tailed t-test at the 0.05 levelof significance, unless otherwise noted.Terms relating to differences, such as‘‘greater than’’ or ‘‘less than,’’ indicatethat the difference is statisticallysignificant. A lack of commentregarding the difference between anytwo estimates does not mean that thedifference was not tested forsignificance.AnalysisResultsDuring 2003–04, there were, onaverage, 161,200 office-based medicalpractices in the United States involving311,200 physicians (Table 1). Although35.8 percent of office-based physicianswere in solo practice, 69.2 percent ofmedical practices consisted of solopractitioners (Figure 1). The one-fifth ofmedical practices with three or morephysicians (19.5 percent) contains aboutone-half of all office-based centThe PII form included questionsused to determine physician eligibilityfor the survey as well as to gatherinformation about the practice, such assize, ownership, and revenue sources.The breadth of specialization forpractices was based on the questions,‘‘Do you have a solo practice’’ and ‘‘Isthis a single- or multi-specialty grouppractice,’’ in which responses of solopractice and single-specialty group werecombined. Physician specialty for solopractices and group practices is alsopresented (see ‘‘Technical Notes,’’Table I for physician specialtydefinitions). The physician specialtycategories grouped specific selfdesignated subspecialty codes providedby the AMA and AOA on the samplingframe. Information on physicianspecialty was updated during theNAMCS induction interview of thephysician.Because estimates presented in thisreport are based on a sample rather thanthe universe of office-based physicians,they are subject to sampling variability.The standard errors are calculated usingTaylor series approximations inSUDAAN, which take into account thecomplex sample design of the NAMCS(10). Estimates based on 20–29 casesand/or estimates whose standard errorsrepresent more than 30 percent of theestimate have an asterisk (*) to indicatethat they do not meet the reliabilitystandard set by NCHS. Chi-square tests3604035.826.921.12014.814.211.4 11.84.10SoloPartner3–5Practice size6–1010.78.41.211 or moreSolo and single- MultispecialtyspecialtygroupgroupBreadth of specialization1See Methods for details on estimating medical practices.Figure 1. Percent distributions of office-based medical practices and physicians withinpractices by size and breadth of specialization: United States, 2003–04

Advance Data No. 383 March 12, 2007and 78.9 and 21.1 percent of allphysicians worked in these practices,respectively. About 79.4 and20.6 percent of all visits, respectively,were to solo and single-specialtypractices and multi-specialty grouppractices. With the exception of visits inthe Northeast, the distribution of visitsby region was similar to the distributionof medical practices. The Northeastaccounted for 23.8 percent of allmedical practices, but only 19.8 percentof visits. The distributions of visits andmedical practices by metropolitan statuswere similar.The distribution of office-basedmedical practices by financial andprocess characteristics is shownaccording to practice size in Table 2. Ingeneral, the percent of revenue frommanaged care contracts increased withpractice size, a pattern that reflects theassociation between having anymanaged care contracts and practicesize. Conversely, the percentage ofpractices without managed carecontracts was inversely related topractice size. A higher percentage ofsmall practices had some or a lot ofdifficulty referring patients with privateinsurance than larger practices.Participation in a practice-based researchnetwork also increased with practicesize, from 2.7 percent for solo practicesto 15.2 percent for practices with 11 ormore physicians. Use of electronicbilling records, electronic medicalrecords, and computerized prescriptionorder entry each increased with practicesize. Other characteristics, such aspercent of revenue from selectedpayment sources, were not associatedwith practice size (Table 2). On average,medical practices received 45.1 percentof revenues from private insurance,36.3 percent from Medicare, and17.1 percent from Medicaid.With regard to the adoption ofinformation technology, 69.2 percent ofpractices had electronic billing records,which translates to 74.2 percent ofphysicians using this technology(Figure 2). The percentage of practicesadopting these systems is lower thancomparable percentages reported byphysicians because use of thesecomputerized clinical support systemsamong physicians increases 2015.06.50Uses electronic billingUses EMR9.2Uses CPOE1See Methods for details on estimating medical practices.NOTES: EMR is electronic medical records. CPOE is computerized prescription order entry.Figure 2. Percent of office-based medical practices and physicians using computerizedadministrative and clinical support systems: United States, 2003–04practice size (11) and consequentlycontributes more frequently to thephysician estimates than to practiceestimates. Similarly, the percentage ofpractices that adopted electronic medicalrecords (15.0 percent) was lower thanthe comparable percentage of physicians(19.0 percent), and the percentage ofpractices using computerizedprescription order entry systems(6.5 percent) was lower than thecomparable percentage of physicians(9.2 percent). This reflects the higherlikelihood of large practices to adoptinformation technology and the fact thatthe percentage of all physicians in thesepractices is higher than the percentageof small practices (11).Finally, Table 3 presents solo andgroup practices in terms of physicianspecialty. In this table, the multispecialty group column represents theresidual after accounting for solo andsingle-specialty group practices. Amongmajor specialties, psychiatric practices(85.6 percent) were most likely tooperate as solo practices while pediatricpractices were least likely to operate assolo practices (52.1 percent). Among the69.2 percent of medical practicesinvolving solo physicians (Table 1), themost frequent specialties were generaland family practice, internal medicine,obstetrics and gynecology (data notshown). Among the 22.4 percent ofpractices organized as single-specialtygroup practices, the top three specialtieswere general and family practice(17.0 percent), internal medicine(13.9 percent), and pediatrics(12.3 percent) (data not shown).DiscussionThis report provides descriptiveinformation on medical practices during2003–04. Practice estimates provide newperspectives on the organization anddelivery of office-based ambulatorycare. Because the physician sampleweight is directly modified by thenumber of physicians in practice toyield a medical practice weight, thedistribution of medical practices oncharacteristics associated with practicesize varied distinctly from thedistribution of physicians on the samecharacteristic. For example, theone-third of office-based physicians whoare in solo practice contrasts with thefinding that two-thirds of medicalpractices consist of solo practitioners.On the other hand, group practices,which account for one-fifth of medicalpractices, contain about one-half of alloffice-based physicians. Estimates ofpractices and physicians are similar onsome but not all characteristics. For

Advance Data No. 383 March 12, 2007example, private insurance and Medicareare the most frequent sources of revenuefor practices and physicians (2). Thepercentage of practice revenue frommanaged care contracts (44.7 percent) isidentical to the previously publishedestimate for physicians (2). Thepercentages of medical practicesadopting electronic medical records orcomputerized prescription order entrysystems, however, were lower than thecomparable percentages reported byphysicians.The overall estimate of grouppractices (three or more physicians)derived from the NAMCS is roughlycomparable to the estimate from theMedical Group Management Association(MGMA). The 2003–04 NAMCSestimated there were 31,400 grouppractices, while the MGMA studyestimated 34,490 group practices in2004 (9). The MGMA estimate,however, included radiology,anesthesiology, and pathology grouppractices, while the NAMCS estimatedid not. After adding the MGMAestimate of anesthesia, radiology, andpathology single specialty groups to the2003–04 NAMCS estimate, the resultingtotal was very close to the total inMGMA’s universe of group practices(12).Although the overall NAMCS andMGMA estimates are similar,definitional differences exist betweenthe two data sets. The MGMA has agreater percentage of large practices anda lower percentage of small medicalgroups than NAMCS (12). The NAMCSpercentage of large practices (11 ormore physicians) among all grouppractices (6 percent) was smaller thanthe comparable MGMA percentage(15.7 percent) (12). Within practiceswith 11 or more physicians, theNAMCS averaged 17.7 physicians perpractice compared with 49.8 physiciansper practice reported by the MGMA(12). Many of these differences stemfrom the definition of practice sizereported in the MGMA. If a medicalgroup was ‘‘subordinate’’ to a largerpractice, MGMA listed only the size ofthe ‘‘parent’’ organization in its database. In contrast, the NAMCS measuredthe practice size at locations where thephysician saw patients; the size of the‘‘parent’’ organization was notmeasured. Finally, the MGMA estimateincluded large Veterans Administrationhospital practices (12); such practiceswere excluded from the NAMCS. Thus,the NAMCS estimates are reasonablebased on the MGMA comparison aslong as the scope of the NAMCS surveyis taken into account.This report has described howestimates of medical practices werederived from the NAMCS physiciandata. These estimates are subject toseveral limitations. First, practiceestimates are subject to variability inhow practice size is defined. For thisreport, practice size was assumed to bethe size indicated in the first-listedlocation. If a different measure of sizewas used to estimate practices, forexample, the location where the majorityof patients were seen, the estimate ofpractices would vary. Second, practicecharacteristics were limited toinformation collected during theinduction interview. The practice sizemight be underestimated if the sampledphysician was an employee and workedwith different practices at differentlocations. The induction interviewquestionnaire did not include questionsthat could identify this situation. Finally,practice estimates derived from sampledphysician data are reasonable only forcharacteristics of the overall practicethat do not vary by physician within apractice, such as the use of electronicmedical records or number of managedcare contracts (Table 2). Practiceestimates from NAMCS data are notreasonable for characteristics that varyamong physicians within a practice. Forexample, variation in physiciancharacteristics and treatment practicepatterns can be collected only fromindividual physicians within practices.Policy makers interested in thestructure and policies of medicalpractices may be interested in thesedata. Practice estimates are an additionalway to monitor the dispersion of newtechnologies and policies of medicalpractices that affect care provided atambulatory medical visits.References1. Schappert SM, Burt CW. Ambulatorycare visits to physician offices,hospital outpatient departments andemergency departments: UnitedStates, 2001–02. National Center forHealth Statistics. Vital Health Stat13(159). 2006.2. Hing E, Burt CW. Characteristics ofoffice-based physicians and theirpractices, 2003–04. Vital Health Stat13(164). 2007.3. Sirken MG. Network Sampling. In:Armitage P, Colton T, eds.Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. p.2977–86. West Sussex, UK: JohnWiley and Sons Ltd. 1998.4. Sirken MG, Levy PS. Multiplicityestimation of proportions based onratios of random variables. J Am StatAssoc 69:68–73. 1974.5. Sirken M, Shimizu I, Judkins D. Thepopulation based establishmentsurvey. Proceedings of the SurveyResearch Section. Am Stat Assoc. p.470–3. 1995.6. Burt CW, Hing E. Making patientlevel estimates from medicalencounter records using a multiplicityestimator. Stat Med. 2007. [Epubahead of print]7. National Center for Health Statistics.Public-use data file documentation.2003 National Ambulatory MedicalCare Survey. Hyattsville, MD. 2005.8. National Center for Health Statistics.Public-use data file documentation.2004 National Ambulatory MedicalCare Survey. Hyattsville, MD. 2006.9. Gans D, Kralewski J, Hammons T,Dowd B. Medical groups’ adoptionof electronic health records andinformation systems. Health Aff24(5):1323–33. 2005.10. Research Triangle Institute.SUDAAN user’s manual, release 8.0.Research Triangle Park, NC:Research Triangle Institute. 2002.11. Burt CW, Sisk JE. Which physiciansand practices are using electronicmedical records? Health Aff24(5):1334–43. 2005.12. Personal communication with DanGans of Medical Group ManagementAssociation. May 6, 2006.5

6Advance Data No. 383 March 12, 2007Table 1. Number and percent distribution of office-based medical practices, physicians within practices, and office visits withcorresponding standard errors, by selected practice characteristics: United States, 2003–04Medical practices1Physicians within otal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .161,2005,300311,200Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .100.0.100.088.311.71.11.1.69.211.414.24.11.2Solo and single-specialty group . . . . . . . . .Multi-specialty group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .StandarderrorOffice visits within 1.1MSA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Non-MSA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .88.311.71.11.174.219.01.21.387.412.61.61.6Average number of physicians8,000Percent distributionNumber of in-scope office locationsOne . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .More than one . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Practice size3Solo . . . .Partner . .3–5. . . . .6–10 . . . .11 or more.Breadth of specializationOwnershipPhysician or group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .HMO4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Other . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Geographic regionNortheast .Midwest . .South . . .West . . . .Metropolitan status51See ‘‘Methods’’ for details on estimating practices.Includes nonfederal physicians who see patients in offices. Excludes radiologists, pathologists, and anesthesiologists.Practice size is number of physicians in the practice.4HMO is health maintenance organization.5MSA is metropolitan statistical area.23NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals because of rounding.

Table 2. Selected characteristics office-based medical practices by practice size with corresponding standard errors: United States, 2003–04Practice size1AllpracticesCharacteristicSoloPartnerPractice size13–56–1011 ormoreAllpracticesSoloPercent distributionPartner3–56–1011 ormoreStandard errorNumber of managed care contractsTotal . . . . .None2 . . . .Less than 3 .3–102 . . . . .11 or more2 .Unknown . 0.9.1.72.23.94.11.2.1.84.64.55.42.2Percent of revenue from managed care contracts2,3. . . . . . . . . 1.61.5Percent of revenue from selected sources4Private insurance2 .Medicare. . . . . . .Medicaid . . . . . . .Other sources2 . . .Any difficulty referring certain typesof patients for specialty consultation5Medicaid . . . . . .Medicare. . . . . . .Private insurance2 .Uninsured . . . . . .42.12.83.74.33.22.84.2Participates in practice-based research network2,6 . . . . . . . . . . . zed adminstrative and clinical support systemsUses electronic billing records2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Uses electronic medical records2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Uses computerized prescription order entry system (CPOE)2 . . . . .Advance Data No. 383 March 12, 2007Mean percentMean percentPercent of prescriptions written using CPOE8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .80.978.7** Figure does not meet standards of reliablity. . . Data not applicable.1Practice size is number of physicians in practice. See ‘‘Methods’’ for details on estimating practices.2Significant weighted linear trend with practice size (p 0.05).3Mean percent among practices with any managed care revenue. The missing value for managed care revenue is 12 percent.4Mean percent of revenue among practices. Sum will approximate a percent distribution but responses were provided as a percentage for each source of revenue. Cases with missing data were excluded (6–15 percent depending on type of paymentsource).5Missing data ranged from

average, 161,200 office-based medical practices in the United States involving 311,200 physicians (Table 1). Although 35.8 percent of office-based physicians were in solo practice, 69.2 percent of medical practices consisted of solo practitioners (Figure 1). The one-fifth of medical practices with three or more physicians (19.5 percent .

![Office 2010 Professional Plus Com Ativador Serial Keyl [EXCLUSIVE]](/img/61/office-2010-professional-plus-com-ativador-serial-keyl-exclusive.jpg)