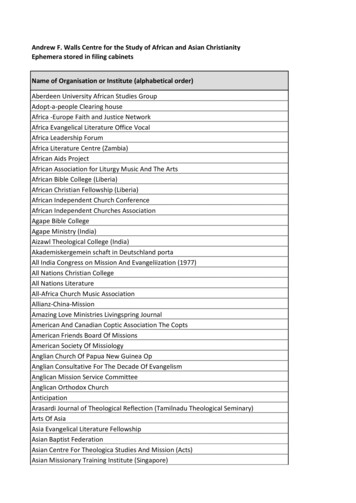

Transcription

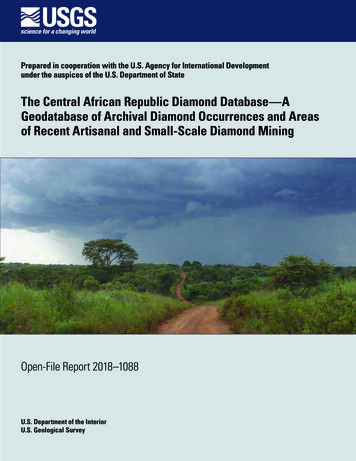

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Developmentunder the auspices of the U.S. Department of StateThe Central African Republic Diamond Database—AGeodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areasof Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond MiningOpen-File Report 2018–1088U.S. Department of the InteriorU.S. Geological Survey

Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006.Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey.

The Central African Republic DiamondDatabase—A Geodatabase of ArchivalDiamond Occurrences and Areas of RecentArtisanal and Small-Scale Diamond MiningBy Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. ClarkPrepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Developmentunder the auspices of the U.S. Department of StateOpen-File Report 2018–1088U.S. Department of the InteriorU.S. Geological Survey

U.S. Department of the InteriorRYAN K. ZINKE, SecretaryU.S. Geological SurveyJames F. Reilly II, DirectorU.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and livingresources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS.For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications,visit https://store.usgs.gov.Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by theU.S. Government.Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materialsas noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner.Suggested citation:DeWitt, J.D., Chirico, P.G., Bergstresser, S.E., and Clark, I.E., 2018, The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A geodatabase of archival diamond occurrences and areas of recent artisanal and small-scale diamond mining:U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2018–1088, 28 p., 1 pl., https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181088.ISSN 2331-1258 (online)

iiiContentsAbstract.1Introduction.1Study Area.2Overview of CAR Surface Geology.2Diamond Deposits.4Background.5Conflict in CAR.5International Diamond Certification.8Methodology.8Compilation of Archival ASM and Diamond Occurrences Dataset.8Development of Recent (2013–2017) Mining Activity Dataset.12Accuracy Assessment in the Carnot Region.16Preliminary Dataset Comparison.16Supporting Geomorphic Data.16DEM Processing .16Hydrologic Datasets.17Surficial Geology and Geomorphology.18Results .20Archival ASM and Diamond Occurrence Results.20Recent (2013–2017) Mining Activity Dataset.20Map Plate.20Dataset Observations.22Discussion.22Artisanal Mining Remote Sensing Challenges.22Differences in Diamond Occurrence Between the Carnot and Mouka-OuaddaFocus Areas.25Conclusion.25References Cited .25Oversize Item [available at https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181088]Plate 1.Surficial and Bedrock Geology, Placer Diamond Deposits, and Mineral Occurrencesof the Central African RepublicFigures1.2.Map of the study area, which includes all of the Central African Republic.3Map showing the Carnot and Mouka-Ouadda Sandstones, located in western andeastern Central African Republic, respectively.43. Diagram showing geomorphic units of channel, alluvial flat, and terrace,which are related to the distribution of diamond deposits in the CentralAfrican Republic.5

ivTables1.2.3.4.5.6.7.Archival sources used to compile historical diamond occurrences.10Attribute information included with each diamond occurrence record.11Numeric codes that indicate specific mining activities in the Recent (2013–2017)Mining Activity Dataset.16Part 1 of the surficial geology and geomorphology model includes zonesof relative height.19Part 2 of the surficial geology and geomorphology model characterizes erosiveand depositional zones by incorporating slope steepness in a path-distancefunction.19Categories of geomorphic units in part 3 of the surficial geologyand geomorphology model.20Accuracy matrix of Carnot region database points.21

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areasof Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond MiningBy Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. ClarkAbstractThe alluvial diamond deposits of the Central AfricanRepublic (CAR) are mined almost exclusively by way ofinformal artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) methods.ASM sites range in diameter from a few meters to 30 metersor more, and are typically excavated by crews of diggersusing hand tools, sieves, and jigs. CAR’s reported annualproduction has ranged from 300,000 to 470,000 carats overthe past decade. This production is significant for CARbecause it accounts for a large portion of the country’s exportincome and employs an estimated 60,000 to 90,000 minersnationally. Diamond production has also been linked to theviolent conflict and political instability which have plaguedthe country for decades. The most recent conflict began in2012 and resulted in an international embargo on the export ofrough diamonds from CAR. This embargo was followed by aceasefire and a return of peace in certain zones of the countryin 2015; however, political and economic instability continuesto afflict many areas of the country. International efforts torestore peace in CAR have included United Nations supportas well as international technical assistance in tracking,assessing, and monitoring diamond production. In 2015, theKimberley Process (KP) developed an operational frameworkallowing for legitimate exports from five subprefectures inCAR that were deemed to be compliant with KP internalcontrols and which were also considered to be free fromsystematic violence or control of armed groups.The goal of this study was to address information gapsregarding the location and extent of diamond occurrences andmining activity through the integration of geologic researchwith remote sensing, geographic information systems analysis,and fieldwork. Effective and efficient monitoring of diamondmining activity using satellite imagery requires detailedunderstanding of the geographic distribution of diamondsources and mining activities.A two-phase methodology was developed to addressthe knowledge gaps. The first phase consisted of the creationof a comprehensive geospatial catalogue of diamond miningand occurrence locations from archival records such ashistorical maps, mining reports, academic publications,and field data. Building upon this locational database, thesecond phase consisted of the creation of a geospatial datasetcataloguing current mining activity locations through manualinterpretation of recently acquired satellite imagery. Theaccuracy of this second geospatial dataset was then assessedusing field observations made between 2016 and 2017 by theU.S. Agency for International Development’s Property Rightsand Artisanal Diamond Development II project. This reportpresents a two-part geodatabase: part 1 contains the locationsof diamond mine sites and occurrences from archival sources,and part 2 indicates areas of current or recent mining activity.This geodatabase is unique in its temporal and spatial extentand may be used to analyze the geographic distribution ofCAR’s known diamond resources, to assess the effect ofrecent violent conflicts and KP actions on diamond production, to provide decision makers with information regardingsmall-scale diamond mining, and to improve the monitoring ofmining in regions of the country prone to conflict.IntroductionDiamond resources in the Central African Republic(CAR) occur in alluvial deposits, all of which are minedthrough artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) methods.Artisanal miners employ teams of diggers to remove surficialsediment layers using hand tools such as sieves and jigs toreveal potential diamond deposits in gravel layers of thesedimentary column (Chirico and others, 2010). Diamondresources are a significant part of the country’s export-basedincome, with reported annual exports fluctuating between

2 The Central African Republic Diamond Database—Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Diamond Mining100,000 and 450,000 carats over the past several decades(Chirico and others, 2010). In spite of these diamondresources, CAR remains one of the world’s least developedcountries (Central Intelligence Agency, 2016; United NationsDevelopment Programme, 2016). Moreover, politicalinstability has plagued the country since its independence in1960, as evidenced by multiple coups, attempted coups, andthe formation and continued presence of several armed rebelgroups (Ghura and Benoît, 2004; International Crisis Group,2007; Giroux and others, 2009; Spittaels and Hilgert, 2009).This violence has displaced more than a million people andmaintained poverty-level conditions for three-quarters ofCAR’s 2.3 million populace (World Bank, 2017). The mostrecent upheaval began in 2012, when an alliance of rebelgroups, known as Séléka, advanced across the country, violently seizing key infrastructure, valuable diamond productionareas, and ultimately government power (International CrisisGroup, 2014). The inclusion of CAR’s diamond productionregions in this violent upheaval led the Kimberley Process(KP), an international organization prohibiting the trade ofconflict diamonds, to temporarily suspend CAR from exporting rough diamonds to the international market (KimberleyProcess Certification Scheme, 2013). The concept of conflictdiamonds, sometimes referred to as “blood diamonds,”emerged in the 1990s to describe situations of violence andarmed conflict that are financed by illegal mining and saleof diamonds (Le Billon, 2008; Chirico and Malpeli, 2014).With the return of peace and government stability in 2015, theKP revised the suspension to allow the export of diamondsfrom specific permitted zones, and committed to supportCAR efforts to reform its diamond sector (Kimberley ProcessCertification Scheme, 2015b).In order to address the full range of political, economic,social, and geographic factors involved in CAR’s diamondmining sector, comprehensive understanding of thegeographic distribution of diamond resources and ASMactivity throughout the country is necessary. Although aninventory of diamond mining sites and diamond occurrenceswas created from U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) archivalrecords and USGS/Bureau de Recherches Géologiques etMinières (BRGM) field data collected between 2006 and2008 (Chirico and others, 2010), the study was done withoutthe benefit of widespread high-resolution satellite imagery,predated the political conflict, and was not published as ageospatial dataset. Other research efforts and datasets relatedto diamond mining in CAR focus on limited geographic areasof the country and thus do not provide the necessary countryscale data.This study presents a two-part geodatabase describing(1) archival ASM and diamond occurrence locations,i and(2) recent (2013–2017) areas of mining activity. It providesa country-scale assessment of the geographic distribution ofdiamond occurrences and ASM activity. This report beginsiDataset includes locational information contained in Chirico andothers (2010).with a detailed overview of CAR’s relevant geology and diamond deposits, then provides additional information regardingCAR’s history and political situation. Next, the methods usedto compile the two-part geodatabase are described. The resultant country-scale datasets are then comparatively analyzed todescribe changes in the spatial distribution of diamond miningactivity in CAR that may correspond to the political conflict.Study AreaIn this study both the compilation of archival recordsand the interpretation of ASM activity from satellite imagerywere conducted within the extent of known secondarydiamond source zones in CAR (fig.1). These diamond sourcezones are primarily concentrated in two areas of the county:(1) a western region around the towns of Nola, Berberati, andCarnot in an area underlain by the Carnot Sandstone; and(2) an eastern region encompassing the areas near Bria, SamOuandja, Kembé, and Grand Nzako in areas underlain by ordownstream from the Moukka-Ouadda Sandstone.Located in the central region of the African continent,CAR is dominated by a tropical savanna climate (Köppenclassification Aw), with year-round temperatures above 18 C(65 F) and a dry winter season. Annual precipitation in thisclimate ranges from 1,381 millimeters (mm) (54 inches [in.])in the northwestern part of the country (near Bocaranga) to1,461 mm (58 in.) in the southeastern part of the country (nearBambouti). Climate along the southern border of the countrytransitions to tropical monsoon, with higher precipitationtotals (averaging 1,740 mm/year [68.5 in/year]) owing toincreased monsoonal rains, and a shorter dry season. Thenorthern-most part of the country experiences a hot semi-aridclimate, with approximately half the annual rainfall (averageof 730 mm/year [29 in/year]) of the southern areas and hotyear-round temperatures above 20 C (https://en.climate-data.org). Because of the large amounts of rainfall and warmtemperatures, vegetation ranges from dense tropical rainforestin the southern part of the country to woody savannah inthe north. The topography of CAR is dominated by low andgently rolling hills, with slightly higher elevations found in thenorthwest and east of the country.Overview of CAR Surface GeologyThe generalized description of surface bedrock geologicunits of CAR provided in this section, together with thedistribution of geomorphic units that are relevant to alluvialdiamond deposits, is illustrated on the map plate. Otherparts of the African continent have experienced multipleperiods of extrusion, rifting, folding, and other metamorphicprocesses during the Precambrian and Paleozoic. However,present-day CAR is underlain by basement rocks of twocratonic nuclei, and has experienced comparatively little

Study Area 315 20 25 AFRICABirao10 CHADMapareaMouka-OuaddaFocus ouarGrand NzakoBambari5 rnot Focus AreaREPUBLIC OFTHE CONGODEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGOELEVATION (m)3001,400075050150100225300 KILOMETERS150 MILESFigure 1. Map of the study area, which includes all of the Central African Republic. However, satellite image interpretationfocused on the western Carnot and the eastern Mouka-Ouadda areas (shown in black outline). m, meters.tectonic or metamorphic processes since Archean emplacement. This Precambrian basement geology consists of twomajor units: a lower granitic-gneissic complex and anupper schisto-quartzitic complex. The older, Neoarcheangranitic-gneissic complex is primarily composed of gneisses,gneissic-migmatitic, granitic, and amphibolitic rocks, whereasthe younger, Neoproterozoic schisto-quartzitic complex iscomposed of quartzitic and schistose rocks. These units areintruded throughout the country by Neoproterozic age rocks(Schlüter, 2006). Over lying Paleozoic units include twoglaciogenic sequences, one named the Mambéré Formationlocated in western CAR, and the other named the KombeleFormation, located in the east. Both units range in thicknessfrom 30 to 50 meters (m) and are similarly composed of basaland flow tills, reworked sandstone, conglomeratic sandstone,and siltstone (Censier and others, 1992; Chirico and others,2010).Two Cretaceous sandstone sequences are discomforablyoverlain by two sequences of Cretaceous-age fluvial depositsthat consist of sub-horizontal sand/conglomeratic units. Onesequence is the 300–400-m thick Carnot Sandstone locatedin southwest CAR and the other is the 500-m-thick MoukaOuadda Sandstone located in northeast CAR (Schlüter, 2006).These units likely extended far beyond their mapped boundaries (fig. 2 and map plate), but have eroded over time to formtwo distinct plateaus that cover approximately 85,000 squarekilometers (km2) in combined area (Censier and Tourenq,1986; Censier and others, 1998; Lescuyer and Milési, 2004).The sandstone units are significant to this research becausethey are thought to be the secondary host rock of colluvialdiamond deposits originating from Precambrian or Paleozoickimberlitic source-rock (Censier and Tourenq, 1986; Censierand others, 1998). Following the deposition of these secondarysource rocks during the Cretaceous, physical and chemicalweathering has since eroded, redeposited, and concentratedthe diamonds into more recent river and terrace deposits. Inthe Cenozoic era, these and other surficial sediments havebeen significantly affected by the chemical alteration that istypical of the intertropical zone and have developed lateriticduricrusts and ferricretes as much as 40 m thick, which extendacross large portions of the country (Petit, 1985; Beauvais andRoquin, 1996).

4 The Central African Republic Diamond Database—Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Diamond Mining20 25 hr urBa eCHAD10 dstoneBangassouuiangOubLobayeDEMOCRATIC REPUBLICOF THE inkoMBambaritoBossangoaBouar5 SUDANMouka-OuaddaSandstoneouBatangafoBah15 REPUBLICOF THECONGOTownSubprefecture boundaryRiverSurrounding countryboundaryWatershed boundarySandstone geologic unitsfrom Lescuyer and Milési, 200400502510050200 KILOMETERS100 MILESFigure 2. Map showing the Carnot and Mouka-Ouadda Sandstones, located in western and eastern Central African Republic,respectively. Each unit extends over 40,000 square kilometers or more.Diamond DepositsNo primary sources of diamonds, such as kimberlites,lamporites, or other geologic deposits, are known to exist inCAR. Although tectonic, mineralogical, and crystallographicevidence has led to theories that undiscovered kimberlitesmay lie to the south of CAR in the Democratic Republic ofthe Congo (Censier, 1996), no direct evidence of such primarydeposits exists. Currently, all known diamond deposits in CARare alluvial. They are principally associated with the CarnotSandstone and the Mouka-Ouadda Sandstone (see fig. 2).These two sandstone formations are considered secondarysource rocks that commonly yield diamonds when eroded(Censier, 1996; Chirico and others, 2010). Efforts to samplethe Carnot and Mouka-Ouadda Sandstones for diamondcontent thus far have been unsuccessful.Throughout CAR, geomorphic terrain features suchas alluvial flats and terraces have a varying, but increasedincidence of diamond occurrence. This is in large partexplained by the colluvial and fluvial erosive processes thathave modified the landscape, eroding the Carnot and MoukaOuadda Sandstones, and ultimately transporting diamondsfrom these secondary source units to in- and near-streamalluvial deposits. Four types of alluvial placer deposits havebeen observed in this region, including channel deposits,alluvial flat deposits, low terrace deposits, and high terracedeposits. The geomorphology of the present landscape isan important factor in the location and quality of diamonddeposits (Sutherland, 1985), and geomorphic units of alluvialflat, high- and low-terrace, colluvial hillslope, and undifferentiated bedrock (shown in fig. 3 and described below) havebeen incorporated into the analysis.Surficial geomorphic units of alluvium, terrace, colluvialhillslope, and undifferentiated bedrock overlain on CAR’sbedrock geology are shown on the accompanying map plate.Alluvial flats exist in proximity to the current channel locationand typically have deep surficial sedimentary layers thatreflect the movement of that channel across the floodplain overtime. This geomorphic unit commonly hosts fluvial diamonddeposits; however, such deposits may require extensiveexcavation owing to the potential depth of surficial sediments.Terrace geomorphic features are located at the periphery of thechannel’s floodplain, and are evidence of a geologically olderfloodplain deposit and an indication of the maximum lateralmovement of the channel through time. These features maybe used to interpret the locations of paleochannel positions far

Background 5DepositsColluvialhillslopeDepth - relative vialflatUndifferentiatedbedrock-20Profile length (m)100200Figure 3. Diagram showing geomorphic units of channel, alluvialflat, and terrace, which are related to the distribution of diamonddeposits in the Central African Republic. m, meters.from the Quaternary channel location. Such features also mayhost fluvial or colluvial diamond deposits. Finally, colluvialhillslopes exist upslope of the terrace deposits and exhibit theweathered material that has been transported downslope fromareas of weathered bedrock and lateritic crusts.A majority of diamonds (85–90 percent) recoveredfrom the alluvium near or downstream of the eastern MoukaOuadda Sandstone are reported as high to medium in quality(Bardet, 1974; Working Group of Diamond Exports, 2012),and generally larger than those recovered from the westernCarnot region. In this western region three to four carat stonesare more common than smaller stones, and larger stones (up to10 carats) are not uncommon. Nevertheless, much of CAR’sdiamond production (65–75 percent) has been recorded asrecovered from the western Carnot region (Bardet, 1974;Censier, 1996). It is possible that the higher production of thewestern zone could result from the higher population densityand mining intensity of that region, as well as the longerhistory of diamond exploration and exploitation. Some reportshave also suggested that unofficial export channels exist inthe eastern Mouka-Ouadda region, the potential of which isexacerbated by CAR’s lower institutional capacity throughoutthe eastern region to monitor such unofficial exports. Thesepotential unofficial export channels could strongly influencethe statistical reporting of diamonds produced from the tworegions (Matthysen and Clarkson, 2013).BackgroundSince its independence from France in 1960, CAR hashad a tumultuous political and economic history, heavilyinfluenced by both internal and transnational conflicts involving a multitude of national and international political actors(Spittaels and Hilgert, 2009). A brief overview of CAR’s recenthistory is given here as context for the datasets published in thisreport. Complete review of the transnational background andpolitical situation of the greater region can be found in Girouxand others (2009), and details concerning the political actors inthe region can be found in Spittaels and Hilgert (2009).Conflict in CARCAR’s economy has been largely driven by the exportof its natural resources, including timber, diamonds, andagricultural products. Although agriculture is the primaryeconomic activity, timber and diamond exports account for alarge portion of the country’s total export value (Matthysenand Clarkson, 2013). Of these key exports, diamonds are ofparticular international interest because of their susceptibilityto theft or exploitation and the potential link to violentconflicts throughout the region. A resource’s susceptibility toillicit activities, referred to as “lootability,” is characterized byits relative geographic location, concentration, mode of exploitation, and value-to-weight ratio (Malpeli and Chirico, 2014).In CAR, surficial diamond deposits are widely dispersed inhinterland regions that are distant from the capital and stateregulation. Furthermore, the high value-to-weight ratio ofdiamonds, and the fact that they can be mined by small-scale,technologically simple methods, makes them a resource that iseasily embroiled in conflict and violence (Malpeli and Chirico,2014). International concern that CAR’s diamond resourceswere fundamentally linked to its recent political upheavalsand violent conflict was largely based on the lack of statepresence and internal controls over diamond production areas,as well as the geographic links between the rebellion and areaswith diamond resources (Kimberley Process CertificationScheme, 2013).

6 The Central African Republic Diamond Database—Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Diamond MiningRecent conflict in CAR has stemmed largely from thedisparity between government investment in the near-capitalarea and the lack of presence and investment in remote partsof the country. This disparity is further complicated by amultitude of state and nonstate actors that exist throughout thecountry (Giroux and others, 2009; Spittaels and Hilgert, 2009).CAR’s army, the Forces Armées Centrafricaines (FACA), issmall and tasked with numerous security challenges, includingguarding the president, guarding state prisons, protecting keyinfrastructure elements, and patrolling the vast remote regionsof the country. In the absence of state presence in these remoteregions, many armed stakeholders have emerged with a vestedinterest in local community or local resources. As detailed inSpittaels and Hilgert (2009), these political actors include: Armée Populaire pour la Restauration de la Républiqueet la Démocratie (APRD)—A rebel movement in thenorth and northwest of CAR, which protests intrusionby Chadian forces and the lack of CAR governmentresponse to this foreign aggression, as well as thehuman rights violations committed by state securityservices and the economic disorder created by thegovernment. Union des Forces Démocratiques pour le Rassemblement (UDFR)—A rebel movement in the northeast ofCAR, which disputes the lack of state investment inhealth care, potable water, education, transportationinfrastructure, and security for the hinterland region. Front Démocratique du Peuple Centrafricain(FDPC)—A rebel movement that reportedly controlsthe main road between the towns of Kabo and Sido;the FDPC lacks a clear political agenda but reportedlyhas Liby

mining activity through the integration of geologic research with remote sensing, geographic information systems analysis, and fieldwork. Effective and efficient monitoring of diamond mining activity using satellite imagery requires detailed understanding of the geographic distribution of diamond sources and mining activities.