Transcription

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsObsessive Compulsive Disorder (3CE)Written by:K McCarthy, BA, MS, JD, NCC 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc.,Adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC1

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsCourse Outline:I. Overview3II. Nature of the Condition and Diagnostic Criteria3III. Comorbidity7IV. Societal Costs and Serious Effects on the Individuals Who SufferFrom OCD10V. Etiology12VI. Treatment14A. Psychodynamic Therapy14B. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy15C. Pharmacological Therapy20D. Group VS. Individual Therapy23VII. Conclusion25References 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC2

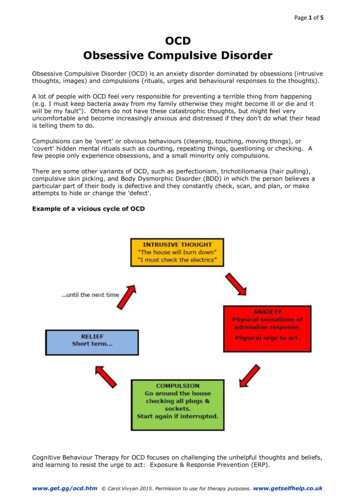

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsI.OVERVIEWObsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by significant recurrentand disturbing thoughts (obsessions) and/or repetitive behaviors (compulsions), whichare usually associated with anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2007;First, Frances, and Pincus, 2004; Lange, Lange, Hauser, Tucha & Tucha, 2012).Between 2 to 3 % of the population suffers from OCD (Lange, Lange, Hauser, Tucha &Tucha, 2012). Recurrent thoughts or worries (obsessions) and experiencing an intensedesire to perform certain actions suggest a significant effect on day-to-day functioningand on quality of life for people who suffer from OCD. This condition is not as wellknown as it should be (Pinto, Mancebo, Eisen, Pagano, Rasmussen & 2006). Thisdisorder can cause detrimental effects on the personal lives of the people who sufferfrom OCD. Social functioning, including work and personal relationships are also oftenaffected. In some cases, close interpersonal relationships can even becomecompromised by this disorder.There are a variety of themes that preoccupy OCD patients. Spreadingcontamination, contracting a disease, causing harm to others, making an importantmistake, committing a religious or moral sin, the possibility of committing homosexual orpedophilic acts are common obsessions (American Psychiatric Association, 2007).Common compulsions include hoarding, cleaning or washing hands, checking to besure a task was done, counting, arranging objects, confessing to sins or errors, andmaking lists.II.NATURE OF THE CONDITION AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIAIn order to correctly diagnose and treat OCD, it is crucial to understand thenature of the condition—its definition, scope and diagnostic criteria. OCD and otherrelated conditions, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia,social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder, are all classified as anxiety disordersin the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2007; First, Frances, andPincus, 2004). However, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases andRelated Health Problems categorizes OCD as a neurotic, stress-related andsomatoform disorder (10th ed., rev.; ICD-10; World Health Organization, 2007; KaiChing Yu, 2013).In a nutshell, OCD involves obsessions and/or compulsions that cause distressor interfere with functioning. Obsessions occur when a person experiences unwantedand distressing thoughts, images, or urges, (Taylor & Jang, 2011) while compulsionsoccur when a person experiences a seemingly uncontrollable desire to engage incertain patterns of behaviors. These compulsions are incredibly intrusive, and are sointense that they lead people to act in a certain way; they make people focus onnegative consequences, which brings about a heightened likelihood of action andfeelings of concern. Once the person has foreseen the possible negativeconsequences, they must decide whether or not to take action in order to prevent harm. 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC3

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsCompulsions are to be distinguished from impulsions. Compulsivity is thedisposition to repeat the same acts or activities and is caused by mental pre-occupationof those activities (Lange, Lange, Hauser, Tucha & Tucha, 2012; Forrester, Wilson &Salkovskis, 2002). Contrarily, impulsivity refers to one’s inclination to act withoutappropriate and sufficient consideration of the consequences of one’s actions. That is,one is impulsive, if, and only if, one acts prematurely without foresight. Interestingly,compulsitivty is caused by increased frontal lobe activity, while impulsivity may becaused by reduced frontal lobe activity (Endrass, Koehne, Riesel, Kathmann, 2013;Colt, 2006; Hauser, 2006; Solomon, 2001; Goleman, 1995). Examining the symptoms ofthese concepts has lead to the identification of several distinguishable, yet correlatedfactors. The scores on each of these factors indicate the severity of a particularsubtype of symptoms. Major factors or symptom subtypes identified in various studiesinclude: (a) checking compulsions; (b) washing rituals; (c) hoarding; (d) orderingcompulsions, which include symmetry and arranging compulsions; (e) cognitiveneutralizing rituals (mental acts aimed at undoing or preventing the anticipated negativeeffects of “bad” thoughts); and (f) obsessions characterized by aggressive, sexual, orreligious themes (Foa et al., 2002; Taylor, Coles, et al., 2010; Taylor & Jang, 2011).The Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group has identified six beliefdomains that increase the likelihood of intrusions: (1) an inflated belief in one’s personalresponsibility for averting danger; (2) a belief that the mere presence of a thoughtindicates it is important; (3) a belief that one can and should control their thoughts; (4)an increased likelihood of perceiving threat; (5) a belief that perfection is necessary inorder to avoid threatening outcomes; and (6) a concomitant intolerance of anyuncertainty. Additionally, clients may present with a belief that anxiety is unacceptable ordangerous (Doron & Kyrios, 2005; Doron et al, 2008; Obsessive Compulsive CognitionsWork Group, 1997).Thus, according to the CBT model, obsessions develop because of the meaninggiven to the experience and/or content of intrusive phenomena, and the resultingresponses or worries regarding these intrusions. As a result, the treatment protocal forindividuals presenting with compulsions/rituals (i.e., overt neutralizing behaviors) andobsessions only (i.e., covert neutralizing behaviors) is quite similar (Maher et al., 2010;Doron & Kyrios, 2005; Doron et al, 2008). For instance, an individual may be highlydistressed by his or her inability to prevent the occurrence of intrusive thoughts that areinconsistent with his or her personal values (e.g., repugnant sexual thoughts). Thisleads to an increased likelihood of dysfunctional responses such as checking theoccurrence of thoughts, attempting to suppress them, or even praying in a ritualizedmanner. Having such responses increases ones likelihood of having reoccurring,unwanted thoughts and experiencing an exacerbation of symptoms (Keeley et al, 2008).The early cognitive models of OCD theorized that compulsive behaviors wereattempts to achieve a sense of control over detrimental consequences. Currently,control issues are associated with the concept of inflated responsibility (attributing tooneself exaggerated ability crucial to bring about or prevent subjectively crucial negative 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC4

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for Professionalsoutcomes) (Salkovskis, 1996). Cognitive models of OCD also focus on the ability tocontrol one’s thoughts; these models suggest that persons with OCD misinterpret theimportance of normal intrusive thoughts, which leads to excessive attempts to controlthem. Having such a disposition to control intrusive thoughts worsens the intrusions andinterferes with one’s ability to foster compulsive neutralization (Rachman, 1998;Salkovskis, 1985, 1996; Wells, 1997).Two control-related constructs have been shown to be especially relevant toanxiety. First, there is the sense of control (or perceived control), which refers to anindividual’s belief about the level of control that is available in any particular context(Skinner, 1996). Having a low sense of control is suggested to lead to one having aninability to cope with threats, which in turn leads to anxiety and avoidant behaviorscharacteristic of anxiety disorders (Barlow, 2008). The second construct is the desire forcontrol (or need for control), which refers to an individual’s general motivation to exertcontrol over life events (Skinner, 1996). Having such a desire for control can motivatean individual to achieve the desired outcome. Such a desire for control tends to bepositively correlated with his or her sense of control (Burger, 1992). Unfortunately, if anindividual fails to achieve the desired level of control, it is believed that he or she willexperience negative emotional states, particularly to anxiety (Burger, 1992; Evans,Shapiro, & Lewis, 1993).The cognitive theory of OCD maintains that when one experiences intrusivethoughts about harm one must decide whether or not they will permit harm to happen.The presence of negative and unacceptable intrusive thoughts was judged by bothobsessional and non-obsessional participants as having the effect of increasingemotional and behavioral responses to ambiguous scenarios. Such a result fits with thenormalizing emphasis of this line of thought.The definition of OCD in the DSM-IV-TR lists five criteria (American PsychiatricAssociation, 2000). The first criterion requires either the presence of obsessions orcompulsions.Obsessions occur when:!Thoughts, impulses, or images are not merely excessive worries about real-lifeproblems.!An individual desires to ignore or suppress such thoughts, impulses, or images,or to neutralize them with some other thought or behavior.!The patient realizes that the obsessions, impulses, or images are a product ofhis or her own thinking.!The recurring and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images are intrusive andinappropriate, and cause marked anxiety or distress (American PsychiatricAssociation, 2000; 2007).Compulsions occur when:!The actions or mental acts are manifested to prevent or reduce distress orprevent some dreaded event or situations. These behaviors or mental acts either 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC5

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for Professionalsare not connected in a realistic way with what they are designed to neutralize orprevent, or they are clearly excessive.!Repetitive behaviors (walking on the stairs repeatedly, washing hands, etc.) ormental acts (counting, praying, etc.) that the person feels driven to perform inresponse to an obsession or according to rigidly applied rules.The second criterion dictates that at some point during the course of the disorder,the person has recognized that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive orirrational. If a person does not recognize that the obsessions and compulsions areexcessive or unreasonable, then the diagnosis is OCD with poor insight. OCD patientsare usually aware, at least at some point in time, that their obsessions or compulsionsare not warranted. People with OCD will have some insight into the fact that theirobsessions or compulsions are illogical or irrational. However, there is a subgroup ofpatients who lack this insight, which actually may be a manifestation of particular OCDsymptoms. That is, the patient's level of anxiety overrules what or she might recognizeas common sense. Still, from time to time, patients will report that they have neverinterpreted the fears or compulsions as less than rational. In one study that involved431patients at 7 outpatient sites, it was reported that 8% of the participants had noinsight at the time of being interviewed while 5% of the participants had neverexperienced insite (Foa et. al, 1995). Additionally, the obsessions of 250 of theparticipants involved some fear of consequences; about 13% felt certain that theconsequence would not occur, 26% were mostly certain that it would occur, and 4%were certain that it would occur.The third criterion states that day-to-day life must be disrupted in order to obtaina diagnosis of OCD. The obsessions or compulsions cause marked distress, are timeconsuming (take more than one hour a day), or significantly interfere with a person'soccupation (or academic) routine, usual social activities, and/or personal relationships.The fourth criterion involves disease-specific manifestations. In otherwords, if theobsessions or compulsions exclusively concern a certain subject matter that isindicative of another Axis 1 disorder, then a diagnosis of such a disorder is appropriate.The following are examples of instances where the content of one’s obsessions orcompulsions will result in a diagnosis other than OCD:!A person preoccupied with food will be diagnosed with an eating disorder.!A person who constantly pulls their hair will be diagnosed with trichotillomania.!A person concerned with their distorted appearance will be diagnosed withbody dysmorphic disorder.!A person consumed with the thought of having a serious illness will bediagnosed with hypochondriasis.!A person experiencing guilty ruminations will be diagnosed with majordepressive disorder.!A person preoccupied with sexual urges or fantasies will be diagnosed withparaphilia. 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC6

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsFinally, the fifth criterion forbids a diagnosis of OCD where the disturbance is due toeither the direct physiological effects of a substance (prescribed medication or illicitdrugs) or a general medical condition.It is important to note that a portion of the psychological community has arguedfor a reclassification of OCD. These individuals advocate for the removal of the label“anxiety disorder” for OCD. This portion of the psychological community feels that itwould be more appropriate to label OCD as an "obsessive-compulsive-related disorder,"which would encompass the related disorders of body dysmorphic disorder, eatingdisorders, trichotillomania, and tic disorders (Stein, 2006). The usefulness andappropriateness of such a reclassification is still under discussion.III.COMORBIDITYThis section discusses the relationship between OCD and other psychiatric ormental conditions. An interview-based study of 334 OCD patients found that only 8% ofparticipants had no psychiatric comorbidity, (LaSalle et. al, 2004) while another studyfound that as many as 91% of its participants had at least one other Axis 1 disorder(Pinto et al., 2006). A more recent study found that as many as 75% of adults with OCDhave at least one comorbid condition (Storch et al, 2010). The most prevalent conditionswere: generalized anxiety disorder; major depressive disorder; social phobia; and panicdisorder; other conditions included: post-traumatic stress disorder; obsessivecompulsive personality disorder; and Tourette syndrome.The presence of comorbid disruptive behavior is thought to actually helptreatment response, as there is typically greater family accommodation, increasedexternalization of problems, and decreased resistance to OCD symptoms (Foa et al.1992). Additionally, similarities have also been observed between OCD and otherconditions, including: bipolar disorder; phobias; eating disorders; panic disorder;generalized anxiety disorder; alcohol dependence/substance abuse; and Tourettesyndrome (American Pyschiatric Association, 2007; Pigott et al., 1994). Patients withOCD, social anxiety disorder, or panic disorder often engaged in trichotillomania, skinpicking, body dysmorphic disorder, and tics; with OCD patients having the strongestassociation with these behaviors (Richter, 2003).In addition to considering other psychiatric diagnoses in the setting of OCD,clinicians should be alert for OCD symptoms in patients who have already beendiagnosed with a different psychiatric illness. For example, eating disorders are oftenaccompanied by anxiety disorders, including OCD. OCD is also common in patientswith Tourette syndrome. One rather large international registry found that 27% of peoplewith Tourette syndrome also had OCD, while other studies have found percentagesranging anywhere from 28% to 62% (American Pyschiatric Association, 2007; Freemanet al., 2000). 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC7

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsDepression is a particularly common comorbidity. Depression, like OCD, isusually accompanied by intrusive, unpleasant thoughts, the difference being that thesethoughts do not generally result in compulsions. The Epidemiologic Catchment AreaStudy in the United States found 67% of individuals identified as having OCD also hadat least one episode of major depression (Dunner, 2001). According to the AmericanPsychiatric Association, as postulated in the DSM-IV-TR, the nine symptoms ofdepression are: 1) suicidal tendency; 2) depressed mood (notice the circularity); 3)significant weight-loss 4) fatigue or loss of energy every day; 5) diminished interests; 6)feeling of worthlessness; 7) excessive or inappropriate guilt; 8) agitation; and 9)insomnia (2000). If a person exhibits at least five of the above symptoms, then he orshe has clinical depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), like OCD, involves excessive anxiety andworry about feared events. Be that as it may, GAD differes from OCD in that GAD ischaracterized by the presence of the following symptoms: restlessness; a tendency tobe easily fatigued; difficulty concentrating; irritability; muscle tension; and sleepdisturbance arousal (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Frances and Ross, 2001;First, Frances, and Pincus, 2004; Spielberger & Sydeman, 1994). Further, whencompared with OCD, the anxiety associated with GAD tends to focus on more realisticproblems and concerns. Anxiety is conceptualized as an emotional state that includesapprehension, nervousness, and worry, along with physiological arousal (AmericanPsychiatric Association, 2000; Frances and Ross, 2001; First, Frances, and Pincus,2004; Spielberger & Sydeman, 1994). Intense physiological activation due to anxietycan cause sleep problems (Zawadzki, Graham & Gerin, 2013).Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) is often found with OCD.OCPD is characterized by having a preoccupation with order, perfection, and control,but not by the presence of obsessions or compulsions (Foa, Kozak & Goodman, 1985).It is usually described as perfectionist personality. Unlike OCD, in order to be diagnosedwith OCPD, symptoms must appear by early adulthood. On the other hand, OCD andOCPD may occur in the same individual (Coles, Pinto, Mancebo, Rasmussen & Eisen,2008). The regularity of both diagnoses occurring together is not known, but studiessuggest that it is not unusual (Coles, Pinto, Mancebo, Rasmussen & Eisen, 2008). Forinstance, a study involving OCD participants found a concomitant rate of between 23%and 32%. However, it is important to note that this sample of participants was notdesigned to be representative of all patients with OCD (Coles, Pinto, Mancebo,Rasmussen & Eisen, 2008). Importantly, studies utilizing community samples estimatethe prevalence of OCPD to be about 0.9% to 2% (Coles, Pinto, Mancebo, Rasmussen &Eisen, 2008). There is also some evidence that OCPD is more common in people withOCD than in patients with other psychiatric disorders.Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is known for its onset in the wake of anextreme traumatic stressor. PTSD symptoms include avoidance of stimuli associatedwith the trauma and persistent thoughts about the event, both of which seem toresemble behaviors and obsessions commonly seen in OCD patients (American 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC8

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for ProfessionalsPsychiatric Association, 2000). On the other hand, the obsessions and compulsionscharacteristic of OCD differ from PTSD symptoms in that they are not caused by aspecific traumatic event.Tourette syndrome is defined by the occurrence of tics that for a majority ofpartients, first manifest during childhood. Unlike OCD, these tics tend to be preceded bya physical sense of "needing" to do the movement, not by anxiety about a specificoutcome or the desire to avert a feared event. Such tics may be quite complex and caneven resemble compulsions, leading to diagnostic confusion in some cases.Delusional disorder often co-exists with OCD and occurs when there is apresence of one or more non-bizarre delusions. The content of the delusions may evenresemble that of an obsession in OCD; for example, a delusion that one has contractedan infection may resemble anxiety about contamination in OCD. Classically, a patientwith OCD would have insight into his or her illness, while a patient with delusionaldisorder would not; however, when insight is lacking, OCD may closely resembledelusional disorder (Foa, Kozak & Goodman, et al. 1995). The DSM-IV-TR suggests thepossibility of adding a diagnosis of delusional disorder in OCD patients whenobsessions reach delusional proportions and are sustained over time (Foa, Kozak &Goodman, et al. 1995). OCD with delusional obsessions may also superficiallyresemble schizophrenia. However, the additional symptoms of schizophrenia willgenerally be lacking (Foa, Kozak & Goodman, et al. 1995).While the criteria for OCD is straightforward, research has demonstrated that thediagnosis is often missed (Foa, Kozak & Goodman, et al. 1995). The BrownLongitudinal Obsessive Compulsive Study has demonstrated this phenomenon since itssubjects first received treatment an average of more than 17 years after having theirfirst obsessive-compulsive symptoms and 11 years after meeting the diagnostic criteria(Pinto, Mancebo, Eisen, Pagano, Rasmussen & 2006). One hurdle to diagnosisincludes patients' reluctance to discuss symptoms. They may be embarrassed to admitto their obsessions, ashamed of the extent to which they pursue compulsions, or theymay even be unaware that treatment is available. The wide differential diagnosis andthe fact that comorbidities are common may also serve to obscure the diagnosis.Symptoms resembling those of OCD can appear in the absence of disease(American Psychiatric Association, 2007). Up to 80% of healthy people have intrusive orunwanted thoughts, and roughly 50% may even have ritualized behaviors (AmericanPsychiatric Association, 2007). Additionally, the thoughts and behaviors experienced byboth healthy people and those diagnosed with OCD may share common themes;(American Psychiatric Association, 2007) the difference being that the symptomsexperienced by healthy people do not cause them distress or interfere greatly with theirfunctioning.Screening tools are available to help evaluate the impact of OCD. One of thebest known is the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). The Y-BOCS 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC9

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for Professionalsincludes two components: a symptom checklist and a severity scale. The Y-BOCS iswidely used in research studies of OCD treatment, with reductions in severity used asmarkers of treatment success. The symptom checklist includes obsessions and bothphysical and mental compulsions. The severity scale is based on: the amount of timespent on obsessions and compulsions; resistance to these symptoms; interference fromsymptoms; related distress; and level of control. Please see the complete checklist klist.pdf, last accessed April 27,2013.IV. SOCIETAL COSTS AND SERIOUS EFFECTS ON THE INDIVIDUALSWHO SUFFER FROM OCDOCD is among the top 20 worldwide causes of disability for people 15 to 44years of age (World Health Organization, 2001). It is estimated that lifetime lost wagesfrom the disorder total 40 billion (Hollander, Kwon, Stein, et al, 1996). Moreover, it isestimated to cost 10.6 billion in annual direct and indirect costs to treat people whohave received a formal OCD diagnosis in the United States (Eaton, Martins, Nestadt,Bienvenu, Clarke & Alexandre, 2008). It is important to note that OCD is actually theleast expensive of all mental disorders, mainly due to the comparatively greaterfunctionality of affected individuals and low frequency of the disorder. OCD can have ahuge impact on one’s life; marriage, sexual functioning, family life, religious expression,leisure activities, and friendships can all be adversely affected by the disorder (Norberg,Calamari, Cohen & Riemann, 2008). For instance, some patients avoid social situationsaltogether because of the embarrassment and/or anxiety that they endure. Otherpatients report that they often have no time for social events and/or that their punctualityand efficiency at work is diminished because performing their compulsions is so timeconsuming. For all of the above reasons, it should come as no surprise that there is areported link between severity of OCD and decreased quality of life (Hollander, Kwon, &Stein, 1996; Eisen, Mancebo & Pinto, 2008; Huppert, Simpson, Nissenson, Liebowitz &Foa, 2009).OCD has been known to affect both men and women about equally, and theprevalence appears to be similar across all races and ethnicities. The NCS-R has foundthat the median age of onset is 19 years of age, with about 1/5 of cases starting beforeten years of age (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Walters, 2005). Other studies suggest a meanage of onset between 22 and 35 years of age, with 1/3 of cases starting before fifteenyears of age (American Psychiatric Association, 2007). Having an early age of onsetappears to be associated with more severe symptoms and higher rates of specificcomorbidities (including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tic disorders, and otheranxiety disorders). Such patients may be less responsive to first-line pharmacologictreatment as adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2007).OCD can also be affiliated with several types of dysfunctional self-perceptions(Doron & Kyrios, 2005; Doron et al, 2008). Anxiety, distress and preoccupation withparticular intrusions may stem from sensitivity in particular self-domains (e.g., jobcompetence), thus hindering therapeutic progress. It is quite common for an individual’s 2018 Ace-Classes, Inc. adapted with permission for ACEonline, LLC10

ACEonline, LLConline-CEs.comOnline Continuing Education for Professionalsself-worth to depend solely on competence in one specific domain (Doron & Kyrios,2005; Doron et al, 2008). Intrusions that challenge an individual’s perception ofcompetence in such a domain will result in both distress and dysfunctional responses.For instance, a client presenting with checking and ordering rituals described hergreatest fear as showing incompetence at work and believed that not getting enoughsleep would lead to her having work problems. As a result, this client spent severalhours a day performing routines (e.g., counting her steps, ordering her room, etc.) thatshe believed would prevent her from having difficulty falling asleep (Doron & Kyrios,2005; Doron et al, 2008).A common overvalued domain in OCD is morality. Some patients have such arigid and limited perception of morality (e.g., being free of sexual urges beforemarriage), that having an urge or thought that challenges their concept of morality leadsto self-criticism, continuous rumination and compulsions (Doron & Kyrios, 2005; Doronet al, 2008). When a client presents with such a limited self-view, special emphasisshould be put on expanding their self-concept. This can be accomplished by mappingadditional important domains for the client, by adding variety to daily activities, byincreasing skills in other domains (using activity scheduling, professional courses, etc.),and by challenging the rigidity and boundaries of the valued domain (e.g., “what doesbeing moral mean to you?”; “what other behaviors/beliefs/attitudes could be included inthis concept?”). The contingency of self-worth and self-domain should be explicitlyexplored, to the point where the client understands the relationship between anxiety andperceptions of failure in that self-domain.Nocturnal growth hormone (GH) secretion is shown to be altered among peoplesuffering from OCD; that is, the release of sleep onset-related GH is dulled, whichcauses sleeplessness (Lange, Lange, Hauser, J., Tucha, &Tucha, 2012). Also, the delayin activation of melatonin causes sleep delay which is also associated with OCD(Lange, K.W., Lange, K.M., Hauser, J., Tucha, L. Tucha, 2012). The relationship of OCDwith GAD, depression and the like has previously been discussed. When an individual issuffering from depression, GAD or OCD, they may become pre-occupied with the causeof their depression or racing thoughts, which often leads to insomnia or sleepdeprivation (Alfano, Ginsburg, & Kingery, 2007; Frances and Ross, 2001; First, Frances,and Pincus, 2004). Thus, a prudent practitioner will realize that the client’s insomniamay be the direct result of the client’s disorder, (Alfano, Ginsburg, & Kingery, 2007;Frances and Ross, 2001; First, Frances, and Pincus, 2004) and that such insomnia canbe cured or treated merely by virtue of treating the underlying mental illnesses, if at all.According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), clinicians shouldunderstand that individuals with OCD are not immune to co-occurring disorders thatmay increase the likelihood of suicidal or aggressive behavior. When such co-occurringconditions are present, it is important to arrange treatments that will enhance

_ ACEonline, LLC online-CEs.com Online Continuing Education for Professionals Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (3CE)