Transcription

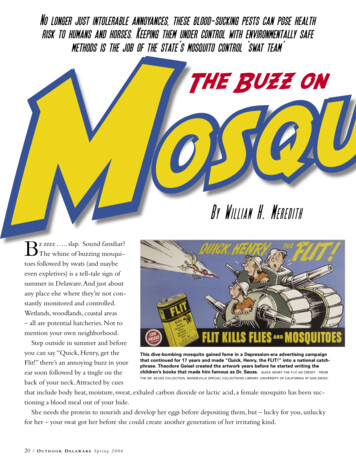

No longer just intolerable annoyances, these blood-sucking pests can pose healthrisk to humans and horses. Keeping them under control with environmentally safemethods is the job of the state’s mosquito control ‘swat team’Bz zzzz . slap. Sound familiar?The whine of buzzing mosquitoes followed by swats (and maybeeven expletives) is a tell-tale sign ofsummer in Delaware. And just aboutany place else where they’re not constantly monitored and controlled.Wetlands, woodlands, coastal areas– all are potential hatcheries. Not tomention your own neighborhood.Step outside in summer and beforeyou can say “Quick, Henry, get theThis dive-bombing mosquito gained fame in a Depression-era advertising campaignthat continued for 17 years and made “Quick, Henry, the FLIT!” into a national catchFlit!” there’s an annoying buzz in yourphrase. Theodore Geisel created the artwork years before he started writing thechildren’s books that made him famous as Dr. Seuss. QUICK HENRY THE FLIT AD CREDIT: FROMear soon followed by a tingle on theTHE DR. SEUSS COLLECTION, MANDEVILLE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT SAN DIEGO.back of your neck. Attracted by cuesthat include body heat, moisture, sweat, exhaled carbon dioxide or lactic acid, a female mosquito has been suctioning a blood meal out of your hide.She needs the protein to nourish and develop her eggs before depositing them, but – lucky for you, unluckyfor her – your swat got her before she could create another generation of her irritating kind.20 /O U T D O O R D E L AW A R E S p r i n g 2 0 0 6

Drinking its fill may take a mosquito a few minutes. By the time youfeel the bite, you already have an itchywelt caused by an allergic reaction toanticoagulants in mosquito saliva.Theanticoagulants allow the littlebuggersto keep siphoning yourblood without clotting once they drillinto a blood vessel. (She doesn’t actuallybite you; six stylets equipped with serrated edges inside her proboscis rip awayat small capillaries just below the surfaceof your skin, creating a pool of blood.)In one feeding, a female mosquito mightmore than double her body weight.Depending upon her species, from a fewto several days later she’ll lay her eggs andgo look for another meal.Delaware hosts 57 mosquito species.At least nineteen of these can dine onhuman blood. Seventeen can make yousick. (See box for the worst culprits).Worldwide, there are around 2,700 different species. It often takes an expert inwing scale patterns and markings on thelegs, proboscis and abdomen to distinguish between them.Only female mosquitoes seek bloodmeals. Males live quite inoffensively onplant nectars and fruits high in sugar; theirprimary role is to mate with females thenthey die. After mating once, females ofmany species can bite again and again toproduce one batch of eggs after another,each time leaving a tiny souvenir of salivato itch and cause varying degrees of misery for their victims.Your biter could have come from avariety of watery environments, somemiles away: a salt marsh, roadside ditch,wet meadow, woodland pool, freshwaterwetland, storm water pond, sewer catchbasin, clogged rain gutter, standing waterin junked tires or empty flower pots, oran uncovered garbage can.You’ll findsome kindofmosquito developingfrom egg to larvae to pupae and finallyemerging as an adult in almost all typesof aquatic habitats in Delaware, whethernatural or man-made. Not much water isneeded: a tablespoon in an old soda can isenough to provide a home for numerouswrigglers.Over the past 20 years, the Asian tigermosquito has become a major pest inDelaware’s cities, towns and suburbs.JAMES GATHANY, CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROLFortunately, mosquito bites only causeirritation, not like the severe reactions tothe venom of yellow jackets, fire ants orAfricanized honeybees. However, likefleas and ticks, mosquitoes are vectors– blood-sucking insects that ingest, alongwith the blood from an infected host,disease-causing organisms such as virusesor other microbes, which they then injectinto a new host when taking their nextblood-meal. Mosquitoes cannot transmitall diseases – HIV for example – but theyare responsible for the spread of a host ofothers, including malaria, yellow fever,dengue fever, canine heartworm, andseveral types of encephalitis, includingWest Nile virus.The latter, which gets itsname from the West Nile region of Africawhere this virus was firstidentified in the 1930s,had never been reportedin North America untilthe summer of 1999 inthe New York City area.Since then it has spreadrapidly across the country,attacking a wide range ofanimals – from sparrows tohorses to humans. Some birds– especially crows and blue jays –are easily killed by the virus. Althoughthe virus can infect humans, we don’tpass it on to the next mosquito that bitesus. Birds as reservoir hosts keep the virusgoing because it replicates easily in theircells. The common house mosquito isthe primary vector for transmitting WestNile to humans.West Nile’s first appearance inDelaware was in 2001.Virus activity peaked in 2003, with 17 confirmedcases involving some pretty sick patientsand two deaths, plus a hundred or soDelawareans who got somewhat sick butdid not seek medical attention, and thuscould not be diagnosed as virus positive.No human cases were reported in 2004and only two cases in 2005; hopefully,numbers will stay low this summer aswell.West Nile illness is characterized byfever, headache, fatigue, muscle pain andsometimes rash. Most cases are mild andgo undetected. Although the illness canbe as short as a few days, in more serious cases, patients can be sick for severalweeks. In its most severe form, which primarily affects the elderly, the virus attacksa person’s nervous system and can causean inflammation of the brain known asencephalitis.West Nile has a fatality rateof about five percent in patients who areseverely infected.Eastern equine encephalitis, or EEE, isa West Nile cousin that is more virulentand deadly, but fortunately much rarer inDelaware and elsewhere. EEE is cycledin nature by a species of mosquitoesthat bites infected birds but doesn’t bitepeople. However, other species that feedS p r i n g 2 0 0 6 O U T D O O R D E L AW A R E /21

DELAWARE MOSQUITO CONTROL SECTIONinsects, small fish and salamander larvaeeat mosquito larvae. Bats, frogs, spiders,purple martins and other birds eat adultmosquitoes.While these predators helpto lower mosquito populations, this usually falls far short of the level of controlthat’s expected and demanded by modernsociety. In addition, mosquitoes have successfully evolved in the timing of theiroccurrences and preferred habitats toavoid being preyed upon.This routinelyallows their numbers to outstrip any natural controls.“The key to mosquito control is knowing when and where they’re occurring,”explains Dave Saveikis, program managerin charge of Mosquito Control in Kentand Sussex counties. “Our emphasis thesedays is on outsmarting them, and to doon both birds and mammals, such as saltmarsh mosquitoes, can pick up the virusand transmit it to horses and humans.EEE kills about a third of those patientswho are severely infected and leaves manysurvivors with nerve damage. Unlikemalaria and yellow fever, which use to beproblematic mosquito-borne diseases inDelaware, modern mosquito control andmodern medicine have not yet been ableto eliminate EEE as a human health concern in our state.For humans, there is no cure for WestNile virus or EEE, only prevention. Forhorses, excellent vaccines are available toprevent these diseases. Keeping mosquitoes at bay by eliminating larval habitats isas important for horses as humans.The good news is that there is very lowprobability that any single mosquito harbors West Nile virus or EEE.The chanceof contracting a mosquito-borne diseaseis still pretty slim, even after receiving numerous bites, but the risk increases, at leasta little, for every bite received.Years ago, mosquito populations wereout of control in many areas of Delaware.Females looking for blood meals besieged22 /O U T D O O R D E L AW A R E S p r i n g 2 0 0 6anyone daring to venture outside in summer. Stories told by “old timers” of cloudsof saltmarsh mosquitoes in numbers sogreat that the sky would literally darkenaren’t just hyperbole.The state’s first line of defense is theDivision of Fish and Wildlife’s MosquitoControl Section.Twenty full-time and15 part-time biologists, conservationtechnicians and other staff, working withan annual operating budget of about 2million, are fighting an ongoing battleagainst a tenacious and adaptable foe.Thisbattle requires constant vigilance and useof a variety of weapons and tactics.Todaymany inhabited parts of the state are relatively mosquito-free, but only becauseof the aggressive prevention and controlwork that goes on behind the scenes tokeep it that way.“Because mosquitoes arise fromnatural, healthy ecosystems, the idea isnot to eliminate every one,” says TomMoran, the regional manager in chargeof Mosquito Control’s northern district.“Our mission is to prevent the proliferation of those that are a health risk,and to limit those that cause intolerablenuisances. And we must do all this usingenvironmentally safe measures.”Dragonfly nymphs, other aquaticDELAWARE MOSQUITO CONTROL SECTIONIn the spring, Mosquito Control employees with backpack sprayers apply preventative larvicides in marshy breeding sites to prevent the mosquitoes from becoming adults.When vast expanses of marsh must be treatedfor mosquitoes, aerial spraying is the only wayto go.that you have to understand their ecologyand behavior to know when and where toattack them.”The Mosquito Control Section’s extensive and intensive surveillance andmonitoring program keeps tabs on bothlarval and adult mosquito populations andthe viruses they might carry. Examiningmosquito populations, including speciestypes and abundances, can involve collecting “dipper” samples to check for larvaein wetlands; collecting adults in lighttraps placed at over 30 permanent stationsaround the state and numerous temporarylocations; or by performing landing ratecounts.The latter involves counting howmany mosquitoes land on the front of afield technician’s body in one minute.The goal is to shoo them away beforethey actually bite, all done while tryingnot to double-count any potential biters.

That’s a real challenge when infestationsstart producing numbers of 50 or moreper minute!The Mosquito Control Section relieson and actually encourages mosquitocomplaints from the public; that helps usfocus control resources. However, it’simperative that property owners also dotheir part to prevent skeeter eruptions byeliminating even small puddles of standingwater. Mosquito Control employees arehappy to help landowners identify problem sites.The search for West Nile entails testing wild birds that are reservoir hosts ofthis virus. People are urged to report sickor dead crows, blue jays, robins, cardinals,hawks and owls that might have contracted West Nile. “Sentinel” chickensare also checked weekly for viral antibodies induced by West Nile or EEE.Theyare placed four to a cage at 22 stationsaround the state. In addition, we lookfor the presence of virus in mosquitoesthemselves. Laboratory analyses for mosquito-borne viruses are conducted by theDelaware Public Health Laboratory.When surveillance and monitoring indicate that control action is needed, “sourcereduction” involving non-chemical controls, is often the method of choice.One such method is stocking native, larvae-eating fishes, primarilymosquitofish, in appropriate habitats.Unfortunately, there are environmentaland logistical factors that limit this type ofbiological control, so it’s not always an effective solution.The primary source reduction tech-Blood samples from sentinel chickens at22 monitoring stations around the stateare tested weekly for mosquito-borneviruses.1. Stay inside when mosquitoes are most active, at dawn and dusk andinto the evening. . And that goes for city slickers and country folksalike.2. If you must be outside, applying an insect repellent containing theactive ingredient DEET can be effective and safe, as long you follow all application instructions on the label. The EPA has recentlyrecognized picaridin and, for the organically inclined, oil of lemon eucalyptus as active ingredients effective in repelling mosquitoes.3. Rid your yard of mosquito habitat by draining areas where larvaemight occur. If you’re producing the pests in your own backyard,chances are they’re going after you first!4. Mosquitoes are attracted to body heat, sweat and skin odor, sosomebody who’s vigorously moving around or exercising can presenta more tempting target.5. The colognes and colorful clothing that make you more attractive toyour own species can make you more attractive to mosquitoes too.6. Wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants helps, but this is not themost comfortable clothing for hot summer months.7. Forget bug zappers. They kill far more non-target insects than mosquitoes themselves, many which are harmless or beneficial species.nique for saltmarsh mosquito control isOpen Marsh Water Management, whichinvolves digging shallow ponds and smallditches in areas of irregularly-floodedcoastal marsh where most saltmarshmosquitoes are produced.This providesgreater access to larval habitats for smallnative fish, primarily killifish, to consumemosquito larvae. OMWM also reversessome of the damage done to marshesthat had been “parallel-grid-ditched”by the Civilian Conservation Corps inthe 1930s, and restores or creates betterhabitat for waterbirds and other estuarineanimals. Because OMWM provides mos-quito control while reducing the need forchemical controls, it has support from awide range of environmental groups andagencies.Around homes or businesses, the primary source reduction method is simplypreventing or getting rid of any unnecessary standing water.This is a simplematter to address, if only more propertyowners would do this! We urge everyoneto help us “fight the bite.”While the Mosquito Control Sectionprefers non-chemical, source reductionS p r i n g 2 0 0 6 O U T D O O R D E L AW A R E /23

methods wherever practicable to use,we must frequently fall back on insecticide treatments. Mosquitoes spend theirfirst several days as aquatic larvae.This isthe easiest time to get rid of them sincethey’re more localized and confined.Larvicides are applied to larval habitats inwetland areas to kill the immature mosquitoes, usually by airplane or helicopter.Roadside ditches are usually treated bytruck-mounted sprayers. Other manmade locations are often treated withhand-applied larvicides.If larviciding doesn’t do the trick, thelast resort is adulticide spraying to killadult mosquitoes that unfortunately areoften widely dispersed.This typicallyentails aerial applications over wide-spread areas that are being plagued bymosquitoes, or by more targeted groundapplications using truck-mounted sprayersor “foggers.”Delaware’s mosquito control seasonstarts in mid-March with aerial larviciding of spring woodland pools beforeforest canopy leaf-out occurs. It continues in many other areas throughout theNot all of Delaware’s 57 species of mosquitoes cause problemsfor people. But here are 13 of the worst culprits. [WNV West Nile virus; EEE eastern equine encephalitis.]Ochlerotatus (Aedes) sollicitans – commonsaltmarsh mosquitoHistorically Delaware’s number one pestmosquito and still a major problem today;breeds in coastal/tidal wetland “potholes”of the high marsh; erupts after lunar tidalfloodings or rains from May until October;bites day/night; long-distance flyer; primaryEEE vector, also found WNV-positive inthe field.Ochlerotatus (Aedes) cantator – brown saltmarsh mosquitoSimilar to the common saltmarsh mosquito,but can appear as early as April; not asabundant in late summer and fall, nor as active during day; an EEE vector, also foundWNV-positive in the field.Ochlerotatus (Aedes) canadensis – woodlandpool mosquitoBiggest spring problem in temporary woodland pools; long-lived; relatively limitedflight range; found WNV-positive in thefield.Aedes vexans – floodwater mosquitoPrefers temporary waters of inland freshwater wetlands and wet woodlots; biggestsummer woodland-pool pest; long-distanceflyer; evening/night biter; EEE vector,found WNV-positive in the field.Aedes albopictus – Asian tiger mosquitoSpread to Western Hemisphere in mid1980s as a result of international trade inused tires; first found in Delaware in 1987,24 /O U T D O O R D E L AW A R E S p r i n g 2 0 0 6now a major urban/suburban problem; doesbest in residential areas where shade andwater-holding containers are common; aggressive daytime biter; limited flight range;found WNV-positive in the field.Ochlerotatus (Aedes) japonicus – Japanese orrockpool mosquitoFirst found in Delaware in 2000; containerbreeder plus occurs in isolated standingwaters; not too numerous yet, but couldbecome a serious urban/suburban problem;found WNV-positive in the field.Culex pipiens – common house mosquitoMajor problem in domestic environs; primarily takes avian blood meals but readilybites humans; container-breeder aroundhouses; also likes sewer catch-basins andstormwater ponds or wastewater lagoons;limited flight range; night biter; can breedcontinuously throughout the summer,producing several generations; the primaryvector in the east for WNV transmission tohumans.Culex salinarius - unbanded saltmarshmosquitoBreeds in standing waters of coastal wetlands, both salt and fresh; night biter; locallyvery abundant; seems to prefer mammals forblood meals; found WNV-positive in thefield.Coquilletidia (Mansonia) perturbans – cattailor irritating mosquitoPrefers freshwater marshes with thick vegetation; one generation per year in latespring/early summer; long-distance flyers;aggressive evening and nighttime biters; EEEvector, found WNV-positive in the field.Anopheles quadrimaculatus – common malaria mosquitoBreeds in permanent waters of freshwaterwetlands; night biter, will enter houses; limited flight range; historic vector for malariain southeastern U.S. as far north as NewYork; found WNV-positive in the field.Psorophora columbiae - dark ricefield orglades mosquitoLikes temporary waters of freshwater wetlands or irrigation systems; long-distanceflyers; aggressive day/night biter; foundWNV-positive in the field.Psorophora ciliata – gallinipperA large mosquito often noticeably alarmingto public; aggressive day/night biter; foundWNV-positive in the field.Culiseta melanura - cedar swamp orblack-tailed mosquitoNot a problem biter for humans, but a majorplayer for cycling viruses (EEE,WNV)in birds that can ultimately affect humansthrough the bites of other mosquito species;found in wet woodlands, but due to its deepwoodland habitats very impracticable to tryto control.

DELAWARE MOSQUITO CONTROL SECTIONspring, summer and fall as we treat variousmosquito production problems in saltmarshes, freshwater wetlands, and urban/suburban environments.The seasondoesn’t end until the first killing freeze ofthe fall.The Mosquito Control Section onlyuses insecticides that are registered by theU.S. Environmental Protection Agencyfor mosquito control purposes.The EPAhas scientifically determined that whenused in prescribed manner, applicationsof larvicides or adulticides pose no unreasonable risks to human health, wildlife orthe environment.The active ingredientsin mosquito control insecticides breakdown quickly in sunlight and water anddo not leave toxic residues. Additionally,modern larvicides have become muchmore target-specific.The Mosquito Control Section putsout information about where and whenspraying will occur with radio announcements, by fax to many federal, state,county and municipal officials, on atoll-free phone hotline (800-338-8181),on DNREC’s website, and via e-mailsto people who have subscribed to theMosquito Control listserver. (To sign up,go to the DNREC homepage, click on“E-mail List Subscription” under servicesand follow directions.)DELAWARE MOSQUITO CONTROL SECTIONVigilant surveillance is key to good mosquito control. Here a technician checks aDelaware saltmarsh – a perfect breedingground for mosquitoes – for larval development.for new ways to conquer mosquitoes– from introducing mosquito pathogensto genetic engineering – the biologistsand technicians of the Mosquito ControlSection will carry on the fight to keep thestate’s mosquito populations at tolerablelevels.However, we might as well face it:mosquitoes have been around for millions of years and they’ll be here longafter we’re gone, despite all our best efforts to eliminate or reduce them. If theonslaught is intolerable, call your localMosquito Control field office at 302-8362555 for New Castle and northwesternKent County, or at 302-422-1512 forthe rest of Kent and all of Sussex County.Otherwise, the best solution is to tryto avoid being where the little buggersabound, or covering up and using a repellent containing DEET.DR.WILLIAM H. MEREDITH IS THEMOSQUITO CONTROL SECTION ADMINISTRATOR. THERE IS MORE INFORMATION ABOUTMOSQUITO CONTROL IN DELAWARE ON-LINEAT HTTP://WWW.DNREC.STATE.DE.US/FW/MOSQUITO.HTM.When larval densities, like that in the dipper, are found in widespread areas, quickcontrol measures are needed to preventfuture misery.The Mosquito Control Section isengaged in applied research projects toimprove surveillance-and-monitoringpractices and our control responses.Wehave a long and fruitful history workingwith University of Delaware researchersto help do this.“Delaware’s Mosquito Controlprogram has developed a realistic andcost-effective approach to mosquito control that makes things bearable and ourmodern way of life possible,” Departmentof Natural Resources Secretary JohnHughes says with pride. “Though the situation is much improved when comparedto historical infestations, Delawareansshouldn’t expect us to eradicate allmosquitoes -- the economic and environmental costs of trying to do this wouldnot be worth the effort.”While researchers continue to lookS p r i n g 2 0 0 6 O U T D O O R D E L AW A R E /25

THE DR. SEUSS COLLECTION, MANDEVILLE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT SAN DIEGO. No longer just intolerable annoyances, these blood-sucking pests can pose health risk to humans and horses. Keeping them under control with environmentally safe methods is the job of the state's mosquito control 'swat team'