Transcription

Designing Roads and Parking AreasDesign VehiclesChapter 8—Designing Roadsand Parking AreasProper road and parking area design is criticalin recreation sites, especially for vehicles towingtrailers. Traffic circulation should be simple,functional, and avoid dead ends.Road System DesignDesigning roads is a complex process that is beyondthe scope of this guidebook. Road geometry andcomponents, including turning radii, sight distances,horizontal and vertical alignments, and intersections,must conform to AASHTO requirements and anyother applicable standards. Consult with a qualifiedtransportation engineer. Designers need to know notonly engineering essentials, but also basic equestrianneeds when designing recreation site roads.simplifies incoming traffic flow and makes sitemanagement easier. Safe exits avoid steep grades andhave adequate clear sight distance for approaches anddepartures. Vehicles towing heavy horse trailers needa lot of time to merge with highway traffic, so makesure merge lanes are long enough.Avoid locating intersections on sharp curves or at areaswith awkward grade combinations. Carry the grade ofthe main road through the intersection and adjust thegrade of the access road to it. The grade of the accessroad should be 6 percent or less where it approachesthe main road. A maximum grade of 5 percent atintersections allows vehicles pulling horse trailers toaccelerate more quickly so they can merge safely intohighway traffic. The preferred grade is 1 to 2 percent.Recreation Site EntrancesThe access to most recreation sites is from a Stateor county highway. Any work performed withinthe rights-of-way of Federal, State, or county roadsrequires applicable permits. The road agencies alsomay require acceleration, deceleration, or turninglanes. During design, carefully analyze the location ofintersections. Use only one site entrance to minimizeconflicts with highway traffic. One entrance alsoFor roads where snow and ice may create poordriving conditions, AASHTO (2001a) lists thepreferred grade on the approach leg as 0.5 percentto no more than 2 percent, as practical. Avoidintersections that are slightly offset from each otheron opposite sides of the main road. More than tworoads intersecting at one location may cause trafficmanagement problems.139Road design is based on vehicle dimensions andoperating characteristics. Transportation engineersmust know which design vehicle is used at the site.In an equestrian recreation site, this is a passengervehicle—a pickup truck—pulling a horse trailer.The standard design length for passenger vehiclesis 19 feet (5.8 meters). Newer model pickup trucksrange from about 15 feet (4.6 meters) long for astandard pickup to about 22.5 feet (6.8 meters) longfor a pickup with an extended cab and long bed.Common horse trailers vary from 16 feet (4.9 meters)long for a two-horse, bumper-pull trailer, to about49 feet (15 meters) long for a six-horse, goosenecktrailer with living quarters. Roads also may need toaccommodate 32- to 46.5-foot (9.7- to 14.2-meter)motorhomes towing horse trailers. If a commercialwaste management company services a facility,garbage trucks may be traveling through the site.Visit with the land management agency to determinethe size of the expected vehicles and whether thesite needs to accommodate maintenance equipment.The Parking Area Layout section in this chapter hasmore information on lengths of common vehicles andslant-load trailers.Some turning radii guidelines are summarized intable 8–1. Tight curves may have to be widenedmore than indicated—consult current AASHTOrequirements for exact figures.8

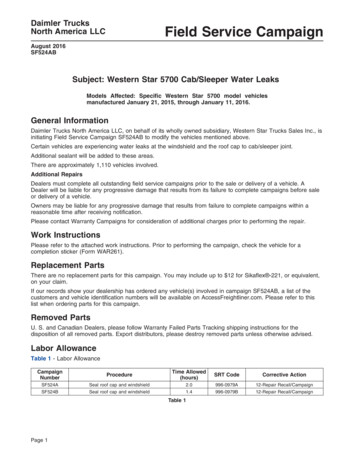

Designing Roads and Parking AreasTable 8–1—Turning radii of some common design vehicles, rounded to the nearest 6 inches.Vehicle typeMinimum insideturning radius (feet)Minimum outsideturning radius (feet)Passenger vehicle with trailer19-foot vehicle plus 30 feet total trailer length (including tongue—49 feet combined length17.534.5Motorhome with trailer30-foot vehicle plus 23 feet total trailer length (including tongue) —53 feet combined length3551.5Garbage truck**Gross vehicle weight (GVW) 20,000 pounds with 25-foot 5-inch wheelbase2133.5* A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (AASHTO 2001)Forest LanesThe number of constructed lanes appropriatefor recreation site roads depends on safetyconcerns and the amount of traffic. Forest Servicerecreation site roads generally are narrow enoughto minimize landscape impacts but wide enoughfor safe travel at up to 30 miles per hour (48.2kilometers per hour).8The Forest Service requires single-lane roads tobe at least 10 feet (3 meters) wide if they servepassenger vehicles moving no faster than 25 milesper hour (40.2 kilometers per hour). Riders oftendrive pickup trucks or motorhomes towing horsetrailers. Because these vehicles require moremaneuvering space than passenger vehicles, manyForest Service recreation site roads are wider than10 feet (3 meters). Single-lane recreation site roads** Architectural Graphic Standards (American Institute of Architects 2000).Trail Talkare often 12 feet (3.6 meters) wide, and double-lanerecreation site roads are often 24 feet (7.3 meters)wide (figure 8–1). Shoulder width depends onavailable space—1 to 2 feet (0.3 to 0.6 meter) usuallyis adequate. Curves need to be widened on singlelane roads to accommodate trailers. In most cases,single-lane roads are constructed no wider than14 feet (4.3 meters). If they are wider, drivers maymistake them for narrow two-lane roads.In a few situations, two-way traffic may be routedalong a single-lane recreation site road. Appropriatesituations include recreation sites where trafficvolume is very low, where the distance is short, orwhere minimal environmental impact is desired.When routing two-way traffic along a single-laneroad, the Forest Service constructs turnouts. Thedimensions and locations of turnouts must follow140established guidelines. Chapter 4 of the RoadPreconstruction Handbook FSH 7709.56 (U.S.Department of Agriculture, Forest Service 1987)has more information on Forest Service design andstandards. The handbook is available at http://www.fs.fed.us/cgi-bin/Directives/get dirs/fsh?7709.56.Recreation roads on public lands are subject tothe AASHTO guidelines for local roads with verylow traffic volume. On low-volume two-lane roadswhere the maximum speed is 30 miles per hour(48.3 kilometers per hour), AASHTO (2001b)recommends a width of 18 feet (5.5 meters). Singlelane roads with two-way traffic often range from11.5 to 13 feet (3.5 to 4 meters) wide.

Designing Roads and Parking AreasTrail TalkForest Lanes (continued)8Figure 8–1—Typical cross sections for roads at recreation sites.141

Designing Roads and Parking AreasRoad AlignmentMinimize landscape alterations by allowingrecreation site roads to complement the site’s naturallandforms. Visitors prefer curves to long straightstretches when they are driving through a recreationsite. However, roads with curves must provideadequate stopping sight distance. Where feasible,roads should follow the contour, avoiding areas ofsteep terrain. Try not to disturb appealing vegetationor significant natural features. In some places, newroad alignments can take advantage of abandonedroads.8Single-lane, one-way loop roads are best for singleparty campgrounds or group sites with individualcamp units. Loop roads make it easy for visitors toget oriented. Managers like loops because they canbe closed as needed. Fit the loops between landforms,dense stands of vegetation, streams, or drainages.These barriers will screen noise and provide privacy.Reduce road and trail duplication by aligning looproads so they lead to site attractions, such as trailaccess points or a lake (figure 8–2). Field experienceshows that to provide an adequate buffer for campunits, the loop road should enclose an area that is atleast 300 feet (91.4 meters) across. If vegetation issparse, allow more distance between the roads.In areas with restricted space, consider incorporatinga double-lane road with a loop turnaround—a cul-desac—at the end (figure 8–3). Make sure the cul-de-sac’sFigure 8–2—Loop roads lead to the lake. The campground loop roads fit between existing vegetation and drainages.142

Designing Roads and Parking Areas8Figure 8–3—This cul-de-sac is large enough to accommodate parking pads.143

Designing Roads and Parking Areasturning radius accommodates the expected sizesof vehicles. Unless the cul-de-sac is large enough,avoid locating parking pads on the turnaround,because it is difficult to maneuver vehicles withtrailers in and out of such areas. An oval-shaped culde-sac accommodates parking pads well. Consult8Figure 8–4—A campground loop road in a restricted space with a high level of development.144Chapter 9—Designing Camp and Picnic Units formore information on parking pads. Another conceptsuitable for tight spaces is shown in figure 8–4.

Designing Roads and Parking AreasRoad GradeRoad ProfileDesign recreation site roads with minimal grades.Wayne Iverson (1985) suggests that the maximumroad grade be 10 percent. A grade up to 12 percentmay be allowed for no more than 100 feet (30.5meters). When the route is considered a pedestrianaccess route, accessibility requirements apply. TheForest Service Outdoor Recreation AccessibilityGuidelines (FSORAG) define an outdoorrecreation access route (ORAR) as a continuous,unobstructed path intended for pedestrian use thatconnects constructed features within a picnic area,campground, or trailhead. The running slope onORARs should be 5 percent or less. On steeperterrain, running slopes up to 8.3 percent are permittedfor as long as 50 feet (15.2 meters). Running slopes upto 10 percent are permitted for as long as 30 feet (9.1meters). Additional accessibility requirements applyand are detailed in the FSORAG. The suggested roadgrades are summarized in table 8–2.Maintain landscape character by fitting recreationsite roads to the natural terrain. The objectives areto keep cuts and fills to a minimum, ease pedestrianflow to facilities, and reduce construction costs. Keepcuts and fills less than 3 feet (0.9 meter). WayneIverson (1985) indicates it is usually possible toraise the finished grade about 6 to 12 inches (152 to305 millimeters) above the natural grade to providedrainage in areas with gentle terrain.Resource RoundupRoad DrainageAvoid site damage by incorporating unobtrusivedrainage structures to carry surface water offrecreation site roads. Use culverts, drop inlets, dips,dikes, curbs, paved or unpaved ditches, and similarstructures where needed. Low-profile culverts anddrainage structures reduce fill requirements. Afterevaluating potential adverse environmental impacts,consider using a ford as a low-water crossing.Table 8–2—Suggested road grades for equestrian recreation site roads.Road elementMinimum grade(percent)Maximum grade(percent)Preferred grade(percent)Interior recreation site roads0102 to 5Site entrance or exit051 to 2Road cross slope(to allow adequate drainage)121 to 2145The Green BookRecreation site roads are subject to guidelinespublished and regularly updated by AASHTO.Be sure to use the most recent editions. A Policyon Geometric Design of Streets and Highwaysaddresses special-purpose roads that serverecreation sites. This comprehensive volume,sometimes called The Green Book, coversdesign speed, design vehicle, sight distance,grades, alignments, lane width, cross slopes,barriers, and related subjects.A companion volume, Guidelines for GeometricDesign of Very Low-Volume Local Roads(ADT 400), addresses design philosophy andguidelines. It also shows examples of unpavedroads and two-way single-lane roads. TheseAASHTO publications are available from thebookstore at https://bookstore.transportation.org/item details.aspx?ID 157.8

Designing Roads and Parking AreasParking Area DesignDesign parking areas to provide smoothly flowingtraffic circulation for vehicles pulling trailers. Avoiddead ends and allow the site’s terrain and vegetationto guide the shape of parking areas. Consult Chapter6—Choosing Horse-Friendly Surface Materialsfor information regarding surface options. Thedifference between equestrian parking areas andstandard parking is the size of the parking spaces.Because riders share most trailheads with many users,prevent conflicts by separating equestrian parkingareas from other parking areas. Consult Chapter7—Planning Recreation Sites for more informationregarding separation. If the trailhead accommodateshikers, mountain bikers, or picnickers, providepassenger-vehicle parking spaces. According to WayneIverson (1985), the minimum size for passenger-vehicleparking spaces in recreation sites is 10 feet (3 meters)wide by 20 feet (6.1 meters) long. Make some parkingspaces longer to accommodate longer pickup trucks.Provide accessible parking spaces. Forest Serviceparking areas must comply with the FSORAG. Figure8–5 shows parking area dimensions for standardpassenger vehicles. If nonequestrians in motorhomesfrequent the area, provide spaces for them. Whilemotorhomes fit into equestrian parking spaces, it isbetter to separate the conflicting uses.8Figure 8–5—Parking dimensions and patterns for standard passenger vehicles. Increase the length of parking spaces if they will be used by pickup trucks with extended cabs and long beds. Forest Serviceparking areas must comply with the FSORAG.146

Designing Roads and Parking AreasMost drivers prefer pullthrough parking spaces thatare angled 45 or 60 degrees, because the angledspace is easier to navigate. Experience shows that thisis true for both equestrian and nonequestrian drivers.Consider parking spaces angled at 90-degrees onlyfor nonequestrian parking.If space is limited, consider incorporating backin parking spaces angled at 45 or 60 degrees. Ifangled back-in spaces are used on single-lane roads,locate the spaces on the driver’s side of the road. Asdrivers back into the spaces, they can see obstacleson the inside of the turn more easily. The parkingconfiguration is more obvious when back-in parkingspaces contain wheel stops. Install the wheelstops inthe parking space, 2 feet (0.6 meter) from the end.Parallel parking spaces, while less desirable thanpullthrough spaces, also may be incorporated. Figure8–6 shows an equestrian parking area where spacerestrictions dictated the use of back-in and parallelparking spaces. A separate entrance and exit makethe most efficient use of space. Landscape islandsand exit and entrance signs guide parking.8Figure 8–6—Equestrian parking in restricted spaces.147

Designing Roads and Parking AreasParking Area GradeFor the safety and comfort of riders and their stock,equestrian parking areas need to be somewhat level.This makes it easier to unload stock and gear, tosaddle an animal, or to spend time in mobile livingquarters. Horses or mules tied to trailers are muchhappier standing for an extended period in a levelarea. The recommended grade for a parking area is 1to 2 percent, a comfortable range that allows properdrainage of rainwater and animal urine. Accessibilityrequirements also stipulate grades within this range.with inadequate space. The horse must stand closeto the trailer, making it difficult to saddle the animalproperly and safely. Figure 8–8 shows horses tied to atrailer with adequate staging area.Parallel stallsSlant-load stallsParking Area LayoutThe appropriate parking configuration depends ondrivers’ parking preferences, the number of parkingspaces desired, and the size of the site. In a groupcamp, some riders are satisfied with an open areawhere they can park as they wish. Others preferto have individual camp units, each with its ownparking pad. Because preferences vary, visit withlocal horse organizations to discover their members’preferred configuration for group parking.8Staging AreasPopular equestrian sites need staging areas where itis easy and safe to unload, groom, and saddle stock.This means providing extra length and width inparking spaces. Extra length allows riders to unloadstock and tie them at the rear of the trailer. Extrawidth allows stock to be tied at the trailer’s side.Figure 8–7 shows a rider saddling a horse in an areaFigure 8–7—Saddling a horse or mule requires access to all sidesof the animal, and tight quarters make the job difficult. Notethe difference in the horse trailers. The trailer on the left hasparallel horse stalls, and the trailer on the right has slant-load—orangled—stalls with a storage area behind the partially closed door.Figure 8–8—Adequate space in parking areas makes it easierand safer to saddle and care for horses and mules. They are morecomfortable and are more apt to wait quietly.148To determine the optimum width for parking spaces,consider the trailer width, stock requirements, andspace needed for walking behind the stock. Generally,trailers are 8 feet (2.4 meters) wide. Stock tied to theside of the trailer need about 12 feet (3.6 meters) atthe side of the trailer, if they stand perpendicular tothe trailer. Another 4 feet (1.2 meters) is needed for aperson to safely walk or lead an animal behind tiedstock. Where space allows, add an extra 4 feet foropen doors on neighboring vehicles, for a parkingspace that is 28 feet (8.5 meters) wide. Figure 8–9illustrates parking and staging dimensions for severalvehicle and horse trailer combinations.Determining the length of a parking space with stagingarea is similar to figuring its width. The minimumlength required for safely unloading a horse or mulefrom the rear of a horse trailer with an open door orramp is 15 feet (4.6 meters). Table 8–3 gives lengths ofcommon vehicles and slant-load trailers, as providedby several horse trailer manufacturers. A slant-loadtrailer allows stock to stand diagonal to the sidewallinstead of parallel (see figure 8–7). A gooseneck traileris similar to a fifth-wheel trailer. An extension (thegooseneck) extends over the pickup bed and is attachedto a ball hitch in the truck bed. Vehicle lengths rangefrom a standard pickup truck pulling a two-horsetrailer to a 44-foot (13.4-meter) motorhome towing asix-horse trailer with living quarters and tack room.Because many campgrounds use a garbage service, thelength of a standard garbage truck is provided.

Designing Roads and Parking AreasTable 8–3—Lengths of vehicles, trailers, and a standard garbagetruck. All trailers are slant loading.VehicleLength(feet)2-horse bumper-pull trailer16*3-horse bumper-pull trailer19*4-horse bumper-pull trailer23*6-horse bumper-pull trailer32*2-horse gooseneck trailer26 to 33**3-horse gooseneck trailer28 to 35**4-horse gooseneck trailer32 to 39**6-horse gooseneck trailer42 to 49**Pickup truck15 to 22.5Motorhome32 to 46.5Garbage truck28* Measurements for bumper-pull trailers include the length ofthe hitch.** Measurements for gooseneck trailers do not include theoverhang above the truck bed.Figure 8–9—Optimum parking and staging dimensions for vehicles towing horse trailers.1498

Designing Roads and Parking AreasA 19-foot (5.8-meter) pickup truck towing a bumperpull, two-horse trailer would need a total length of55 feet (16.8 meters) to park and unload safely. Thisincludes a 15-foot (4.6-meter) unloading area pluswalking space at both ends of the vehicle. A fourhorse gooseneck trailer drawn by a 19-foot pickuptruck would need 78 feet (23.8 meters) for parkingand loading. A 78-foot-long parking space coversmost parking and loading needs. Forty-two-foot(12.8-meter) motorhomes pulling six-horse trailerswith interior living quarters may need a space 110feet (33.5 meters) long (figures 8–10 and 8–11). Ifthese long trailers are common or expected in thefacility, provide several longer spaces for them. Iflocal riders commonly use two-horse trailers, providesome 55-foot- (16.8-meter-) long spaces for them.flexibility, an open parking area is appropriate for agroup camp or trailhead. Where possible, locate openparking areas in a large, sparsely vegetated area witha slope no steeper than 4 percent.Figure 8–10—Horse trailers come in many different sizes andconfigurations. Common slant-load gooseneck trailers range fromabout 26 to 49 feet long.Trail Talk8Spatially ChallengedDesigners laying out the Blue Mountain HorseTrailhead near Missoula, MT, had very littlespace to provide rider, pedestrian, and bicyclistfacilities. Local riders wanted parking areas thatwere 30 feet (9.1 meters) wide to accommodatestock tied to the sides of trailers. Doing so wouldhave greatly reduced the number of equestrianparking spaces. To resolve the problem, plannerschose 18-foot- (5.5-meter-) wide parking spacesand provided ample hitch rails nearby. For moreinformation about this trailhead, see Chapter16—Learning From Others.Figure 8–11—Some vehicles carry up to eight horses, containliving quarters, and include storage space.Open Parking AreasSome riders prefer a parking area that does nothave defined parking spaces. This allows driversto arrange vehicles in a manner that best suits theirneeds. When space is plentiful and riders want150Riders want to park facing the exit as they arrive,orienting their vehicles for an easy departure. Theparking area should be large enough for undefinedparking spaces 28 feet by 78 feet (8.5 meters by 23.8meters) and aisles that are 15 feet (4.6 meters) wideper lane. The generously sized parking area willallow many parking configurations. Designers mayplan one parking configuration and riders may parkin a very different way. Figure 8–12 illustrates theplanned configuration for a group camp and howhorse groups, such as 4-H clubs, often park in theallotted space. The impromptu arrangement opensthe center area for the club’s activities.A variation of the open parking area conceptincorporates several small parking areas (figures8–13 and 8–14). The small areas help break up theexpanse of a large parking area and may be moreattractive. In a group camp, having more than oneparking area provides flexibility. A few differentgroups could use the site simultaneously or one largegroup could occupy all the parking areas.

Designing Roads and Parking Areaspwp8upFigure 8–12—Designed parking compared to actual parking patterns.Figure 8–13—A recreation site for three small groups or one large group. An activity area is located inthe center.151

Designing Roads and Parking AreasSmall Parking AreasFigure 8–15 shows a parking concept appropriate forsmall trailheads. The circulation pattern includes aloop turnaround to prevent vehicles from becomingtrapped when all parking spaces are full. Becausethe parking area is not paved, arrows cannot markthe direction of traffic flow. In the United States,designers can use a counter-clockwise traffic flowthat takes advantage of the familiar right-handdriving pattern. Landscape islands guide vehicletraffic and determine parking orientation. Directionalsigns may be a helpful addition, along with wheelstops.8Figure 8–14—A group camp parking area that can be used by two small groups or one large group.152

Designing Roads and Parking Areas8Figure 8–15—Loop parking at a trailhead.153

Designing Roads and Parking AreasParking DelineationBecause paved equestrian parking areas are notrecommended, delineating the parking spacesbecomes a challenge. Many agencies don’t delineateparking spaces. Where delineation is necessary,striping is just one of several alternatives.Trail TalkDelineating With ConcreteIn the Southwest, where plowing and gradingare uncommon, some land management agenciesuse concrete delineators (figure 8–16). Thedelineators are durable enough to resist chippingor breaking when an animal steps on them.Because they are buried in the ground, theywill be damaged if areas are graded. To reducetripping, they are maintained flush with the roador parking surface (figure 8–17). When paintedwith white reflective traffic paint, the markersare easily visible.8Resource RoundupMarking the SpotIn 2002, the San Dimas Technology andDevelopment Center (SDTDC) conducted asearch for ways to designate parking on unpavedand gravel parking areas. The ideal solutionwould reduce traffic and eliminate confusion andother parking problems. The study investigatedwheel stops, striping, construction whiskers, anda soil stabilizer. Designating Parking Areas onUnpaved Surfaces describes the results of thestudy and is available at 14.html.Concreteparking markersFigure 8–16—Concrete markers are used to delineate unpavedparking spaces in some areas of the country.Figure 8–17—A concrete parking marker.154Existing VegetationIf there is natural vegetation in a planned parkingarea, consider preserving it and turning thesurrounding area into a landscape island (see figures8–14 and 8–15). The vegetation visually breaks upthe parking area, and the landscape island can guidemotorized traffic and provide a spot for drainagebasins. Where vegetation is sparse, preserve or planttrees and shrubs along parking area perimeters andin islands. The plantings relieve visual monotony, andthe shade is invaluable in hot weather.

Designing Roads and Parking AreasRoad and Parking Area SurfacesEquestrians frequently ride or stand on interiorrecreation site roads, in parking areas, and onparking pads. Many times these areas are paved withasphalt, chip seal, or concrete—surfaces that are notrecommended for equestrian use. Pavement and stockdon’t mix well because the hard surface providespoor traction for metal horseshoes. Aggregate is therecommended surface for equestrian recreation areas,because it is slip-resistant, doesn’t allow water topool, and is comfortable to stand or walk on.Pavement can be used for exterior recreation siteroads, which often receive more traffic than interiorroads (figure 8–18). Major benefits to pavingexterior roads include minimizing dust and reducingmaintenance requirements. Because horses usuallydon’t use exterior recreation site roads, pavementthere generally doesn’t pose a hazard. If pavedexterior roads lead to trail access points, construct anadjacent, unpaved trail for horses and mules.At a trailhead intended for shared use, apply aggregateonly in the section where riders unload and saddlestock before a ride. Pave the remaining nonequestriansections of the parking area (figure 8–19). ConsultChapter 6—Choosing Horse-Friendly SurfaceMaterials for more information regarding surfaces.8Site host unitFigure 8–18—Pavement should not be used in equestrian areas. Paving the exterior recreation site road is an exception to this rule because stock seldom travel there.155

Designing Roads and Parking Areas8Figure 8–19—When user groups are separated, surface materials can match the needs of different groups. In this illustration, the equestrian parking area is surfaced with aggregate and the nonequestrianparking area is paved.156

Designing Roads and Parking AreasTraffic ControlAvoid placing barriers that restrict vehicles alongthe perimeters of site roads and parking areas thatare traveled by stock. Barriers in these areas canbe dangerous for stock and riders. Some stock maybecome nervous around barriers, such as woodbollards. This is especially true if the passagewaybetween the bollards is constricted. Attempts to rideor lead a nervous animal through the barrier mayproduce a rodeo. While there are no completelyhorse-safe barriers, a wood or steel railing is suitable(figure 8–20). Make sure barriers have no sharpedges or other potential hazards. Large bouldersappear more natural to a horse or mule and may bean alternative to bollards.Figure 8–20—A horse-friendly steel barrier.8157

Designing Roads and Parking Areas8158

Designing Roads and Parking Areas 8 140 Table 8–1—Turning radii of some common design vehicles, rounded to the nearest 6 inches. * A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (AASHTO 2001) ** Architectural Graphic Standards (American I