Transcription

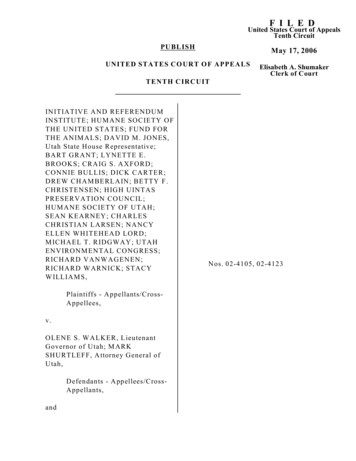

F I L E DUnited States Court of AppealsTenth CircuitPU BL ISHMay 17, 2006UNITED STATES CO URT O F APPEALSElisabeth A. ShumakerClerk of CourtTENTH CIRCUITIN ITIA TIV E A N D REFER EN DUMIN STITUTE; H U MA N E SO CIETY OFTH E U NITED STA TES; FU N D FORTH E A NIM ALS; DAVID M . JONES,Utah State House Representative;BA RT G RA NT; LYN ETTE E.B RO O K S; C RA IG S. A X FO RD;CONNIE BULLIS; DICK CARTER;DREW CH AM BERLAIN; BETTY F.C HRISTEN SEN ; H IG H U IN TASPRESERV ATION CO UN CIL;H U MA N E SO CIETY O F U TA H;SEAN KEA RN EY; CH AR LESCHRISTIAN LARSEN; NAN CYELLEN WH ITEH EA D LO RD ;M ICHA EL T. R ID G WA Y ; U TAHEN VIRO NM EN TA L CONGRESS;R ICHA RD V A N WA G EN EN ;RICHARD W ARNICK; STACYW ILLIAM S,Plaintiffs - Appellants/CrossAppellees,v.OLENE S. W ALKER, LieutenantGovernor of Utah; M ARKSH URTLEFF, Attorney General ofUtah,Defendants - Appellees/CrossAppellants,andNos. 02-4105, 02-4123

U TA H WILD LIFE FED ER ATION;UTA H FO UN DA TION FOR N OR THAM ERICA N W ILD SHEEP;SPO RTSM EN FO R FISH A N DW ILD LIFE/SPO RTSM EN FO RH A BITA T; U TA H FA RM B UR EAUFEDERATION; UTAH BOW M AN'SA SSO CIA TIO N ; R EPR ESEN TATIVEM IK E STY LER ; PR OFESSO R HALL. BLACK; PROFESSOR TERRYM ESSM ER; M S. CINDY LABRUM ;M R. KEN JONES; M R. KARLM ALONE; DR. CHARLES C.ED W ARD S,Amici Curiae.APPEAL FROM THE UN ITED STATES DISTRICT CO URTFOR T HE DISTRICT OF UTAH(D.C. No. 2:00-CV-00836)Lisa W atts Baskin (Robert R. W allace with her on the briefs), of Plant, W allace,Christensen & Kanell, Salt Lake City, Utah, for Plaintiffs-Appellants/CrossAppellees.Thom D. Roberts, Assistant Attorney General (M ark L. Shurtleff, AttorneyGeneral, with him on the briefs), Salt Lake City, Utah, for DefendantsAppellees/Cross-Appellants.Richard G. W ilkins, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University,Provo, Utah, John D. Ray, Jennifer E. Decker, and M atthew B. Hutchinson ofFabian & Clendenin, Salt Lake City, Utah, filed an amici curiae brief for the UtahW ildlife Federation, et al., in Support of D efendants-Appellees/Cross-Appellants.-2-

Before TA CH A, Chief Circuit Judge, EBEL, KELLY, HENRY, BR ISC OE,L UC ER O, M U RPH Y, HA RTZ, O’BRIEN, M cCO NNELL, andT YM K O VIC H, Circuit Judges.M cCO NNELL, Circuit Judge.The Utah Constitution allows voters to initiate legislation “to be submittedto the people for adoption upon a majority vote of those voting on thelegislation.” Utah Const. art. VI, § 1(2)(a)(i)(A). Initiatives related to wildlifemanagement, however, are subject to a special standard: “legislation initiated toallow, limit, or prohibit the taking of wildlife or the season for or method oftaking wildlife shall be adopted upon approval of two-thirds of those voting.” Id.art. VI, § 1(2)(a)(ii). The Plaintiffs, including six wildlife and animal advocacygroups, several state legislators and politicians, and more than a dozenindividuals, bring a facial First Amendment challenge to this supermajorityrequirement. Their principal claim is that by raising the bar for wildlifeinitiatives, the provision imposes a “chilling effect” on the exercise of their FirstAmendment rights, and does so in a manner that is both impermissibly contentdiscriminatory and overbroad. The district court held that the Plaintiffs hadstanding to raise their challenge, but dismissed their First Amendment claim onthe merits. W hile this case w as on appeal, the Plaintiffs’ position gained supportfrom another Circuit. In Wirzburger v. Galvin, 412 F.3d 271, 279 (1st Cir. 2005),-3-

the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that a state constitutional provisionprohibiting ballot initiatives on a particular subject constitutes a restriction onspeech subject to intermediate scrutiny.W e affirm the district court in both respects. W e hold that some of thePlaintiffs have standing to challenge Utah’s supermajority requirement forwildlife initiatives and that the case is ripe and otherw ise justiciable.Respectfully disagreeing with the First Circuit, we hold that a constitutionalprovision imposing a supermajority requirement for enactment of initiatives onspecific topics does not implicate the freedom of speech.I. Facts and Procedural H istorySince 1900, the Utah Constitution has vested the legislative power of thestate not only in the state Senate and House of Representatives but in “the peopleof the State of Utah.” U tah Const. art. VI, § 1(1)(b). The people exercise theirlegislative power as provided in Article VI, Section 1(2), which grants voters theauthority to initiate legislation to be voted up or down by a majority of voters in ageneral election. See id. art. 6, § 1(2)(a)(i)(A). Utah was the second state in theUnion to extend the power to initiate legislation to citizens. See Thomas E.Cronin, Direct Democracy: The Politics of Initiative, Referendum, and Recall 51(1989). From 1960 to 1998, voters initiated fifteen ballot measures. Two ofthese won approval at the polls. See State of Utah Elections Office, Results ofUtah Initiatives and Referendums, 1960-2000,-4-

at andReferendums.htm.None of those initiatives dealt with wildlife management issues, butwildlife and animal rights advocates saw an opportunity to succeed at the ballotbox where they had been stymied in the state legislature. In 1991, a group ofcitizens comm issioned a public-opinion survey regarding cougar and bear huntingmethods to determine whether a ballot initiative was likely to succeed.M eanwhile, they used the threat of a statewide wildlife initiative as a bargainingtool in negotiations with state officials. In several other W estern states, nationalgroups sponsored high-profile animal protection and wildlife initiatives, andbelieved that they could mount a similar campaign in Utah. According todocuments submitted by the Plaintiffs, by 1996 a group called the CougarCoalition had announced its mission to “advance the cause of predator protection. . . by taking our cause directly to the citizens of Utah by means of an initiative.”App. 62. In January 1997, the Humane Society of the United States commencedplanning in Salt Lake City for a wildlife initiative in Utah.In February 1998, two-thirds of the members of both houses of the Utahlegislature passed resolutions endorsing an amendment to Article VI, Section 1 ofthe state constitution:[L]egislation initiated to allow, limit, or prohibit the taking of wildlife orthe season for or method of taking of wildlife shall be adopted uponapproval of two-thirds of those voting.-5-

Utah Const. art. VI, § 1(2)(a)(ii). The proposed amendment, dubbed “Proposition5,” w as slated for a popular vote during the November 1998 general election. Ata meeting of the Utah Constitutional Revision Commission in August 1998,several proponents explained the reasons for their support of Proposition 5. StateRepresentative M ichael Styler praised the performance of existing regionalwildlife management councils and “expressed concern that certain groups fromoutside the state want to manage Utah wildlife practices through initiativepetition.” App. 55. Don Peay, representing a group called Utahns for W ildlife,put it more bluntly, calling Proposition 5 “an effort to preserve Utah’s wildlifepractices from East Coast Special Interest groups” who planned to press “theW ashington DC agenda” through the initiative process. Id.In the 1998 general election, 56% of voters approved Proposition 5, and theamendment went into effect on January 1, 1999. Since then, no group orindividual has pursued a wildlife initiative in Utah.The Plaintiffs filed this lawsuit on October 23, 2000, alleging that thesupermajority requirement created by Proposition 5 impermissibly burdens theexercise of their First Amendment rights, violates the First Amendment onoverbreadth grounds, and violates the Equal Protection Clause of the FourteenthAmendment. They also alleged various violations of the Utah Constitution. TheDefendants countered that the Plaintiffs lacked standing to bring their facial-6-

challenge, and that in any case the Plaintiffs’ First Amendment claims failed as am atter of law .The district court held that the Plaintiffs “clearly have standing to bringthis suit.” Initiative & Referendum Inst. v. Walker, 161 F. Supp. 2d 1307, 1309(D . Utah 2001). It concluded that the Plaintiffs had alleged an “injury in fact,”noting that although the Plaintiffs had not participated in a ballot initiative drivesince the passage of Proposition 5, they had “demonstrated through a number ofaffidavits that they have used the initiative process often in the past and are likelyto in the future.” Id. at 1310. A causal connection existed between the claimedinjury and the challenged conduct, according to the district court, because “[i]fthe Amendment is unconstitutional, then Plaintiffs’ injury is directly traceable tothe existence of the Amendment.” Id. The district court also found the Plaintiffs’challenge ripe, holding that under the “relaxed” standards for ripeness in facialchallenges under the First Amendment, they had alleged a present injury: acontinuing chilling effect on their First A mendment rights, and “higher costs ingetting an initiative passed” in the future. Id. at 1311–12. It also rejected theDefendants’ argument that the case was not ripe for review because theamendment did not in fact have a chilling effect on the Plaintiffs’ speech, notingthat “it would be inappropriate to dismiss the case on ripeness grounds becauseone might find that the Free Speech claim is not meritorious.” Id.-7-

On the merits, however, the district court granted the Defendants’ motion todismiss the Plaintiffs’ facial First Amendment claims, concluding that thesupermajority requirement did not amount to a “restriction” on speech at all. Therule “makes it more difficult to pass a wildlife initiative,” the court noted, “but itdoes not prohibit people from talking about such issues at all.” Id. at 1313. Thedistrict court disagreed with the Plaintiffs’ characterization of the amendment asview point discrimination, finding that “no view point or content is subject todiscrimination or occlusion from public discussion,” in part because “‘peopleinterested in wildlife’ or environmentalists are not homogeneous groups and beinga member of one of these groups does not suggest that one would have adiscre[te] ‘viewpoint.’” Id. at 1314.The Plaintiffs agreed to a dismissal without prejudice of their state law andequal protection claims, and on appeal press only their First Amendmentchallenge. The Defendants cross-appeal the district court’s denial of their motionto dismiss on standing and ripeness grounds. A three-judge panel of this Courtheard oral argument on September 15, 2003. Because of the importance of thestanding and First Amendment issues at stake, however, we set the case for initialen banc review and reheard the case en banc on November 15, 2005.II. StandingAlthough this Court finds itself more closely divided on the question ofstanding than on the underlying First Amendment claim, we cannot reach the-8-

merits based on “hypothetical standing,” any more than we can exercisehypothetical subject matter jurisdiction. See Steel Co. v. Citizens for a BetterEnv’t, 523 U.S. 83, 94 (1998) (rejecting the doctrine of “hypotheticaljurisdiction,” once embraced by some courts of appeals as a way to avoid difficultjurisdictional questions when the merits could be more easily resolved). W etherefore begin by determining whether the Plaintiffs have standing to bring theirFirst Amendment claim.A.The role of federal courts in our democratic society is “properly limited.”Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 750 (1984); see also Valley Forge Christian Coll.v. Ams. United for Separation of Church & State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464, 476 (1982).Rather than being constituted as free-wheeling enforcers of the Constitution andlaws, the federal courts were limited to what James M adison called “cases of aJudiciary Nature,” 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, at 430 (M axFarrand ed., 1911), and Article III of the Constitution calls “cases” and“controversies.” U.S. Const. art. III, § 2. Concern for this limited judicial role isreflected in the principle that, for a federal court to exercise jurisdiction underArticle III, plaintiffs must allege (and ultimately prove) that they have suffered an“injury in fact,” that the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action of theDefendants, and that it is redressable by a favorable decision. Lujan v. Defendersof Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560–61 (1992). Particularly important, for present-9-

purposes, is the requirement of an “injury in fact,” which the Supreme Court hasdefined as “an invasion of a legally protected interest which is (a) concrete andparticularized and (b) actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical.” Id. at560 (internal quotation marks, citations, and footnote omitted). “Allegations ofpossible future injury” do not satisfy the injury in fact requirement, Whitmore v.Arkansas, 495 U.S. 149, 158 (1990), though a plaintiff need not “expose himselfto actual arrest or prosecution to be entitled to challenge a statute that he claimsdeters the exercise of his constitutional rights,” Steffel v. Thom pson, 415 U.S.452, 459 (1974). For purposes of the standing inquiry, the question is notwhether the alleged injury rises to the level of a constitutional violation. That isthe issue on the merits. For standing purposes, we ask only if there was an injuryin fact, caused by the challenged action and redressable in court.The injury alleged by the Plaintiffs in this case is a chilling effect on theirspeech in support of wildlife initiatives in Utah. This Court has recognized that achilling effect on the exercise of a plaintiff’s First Amendment rights may amountto a judicially cognizable injury in fact, as long as it “arise[s] from an objectivelyjustified fear of real consequences.” D.L.S. v. Utah, 374 F.3d 971, 975 (10th Cir.2004); see Ward v.

Thom D. Roberts, Assistant Attorney General (Mark L. Shurtleff, Attorney General, with him on the briefs), Salt Lake City, Utah, for Defendants-Appellees/ Cross -Appellants . Richard G. Wilkins, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, John D.