Transcription

For VannieShou you you 受 又

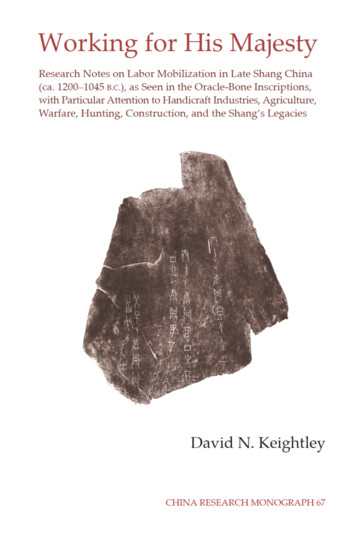

A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California,Berkeley. Although the institute is responsible for the selection andacceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinionsexpressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors.The China Research Monograph series is one of several publication seriessponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with itsconstituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series,the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and PolicyStudies series.Send correspondence and manuscripts toKatherine Lawn Chouta, Managing EditorInstitute of East Asian Studies2223 Fulton Street, 6th FloorBerkeley, CA 94720-2318ieaseditor@berkeley.eduLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataKeightley, David N.Working for His Majesty : research notes on labor mobilization in late ShangChina (ca. 1200-1045 B.C.), as seen in the oracle-bone inscriptions, with particularattention to handicraft industries, agriculture, warfare, hunting, construction,and the Shang’s legacies / by David N. Keightley.pages cm. -- (China research monograph ; 67)Summary: “Dealing with the Shang dynasty (ca. 1200-1045 B.C.), the first to leavewritten records in North China, this work focuses on the artisan corps, labormobilization, farming, warfare, hunting, building, leadership, and culture”-Provided by publisher.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 978-1-55729-102-8 -- ISBN 1-55729-102-01. China--History--Shang dynasty, 1766-1122 B.C.--Sources. 2. China--Economicconditions--To 1644--Sources. 3. Oracle bones--China. 4. Industrialmobilization--China--History--To 1500--Sources. 5. Laborsupply--China--History--To 1500--Sources. 6. Artisans--China--History--To1500--Sources. 7. Farmers--China--History--To 1500--Sources. 8. Soldiers-China--History--To 1500--Sources. 9. Hunters--China--History--To 1500-Sources. 10. Building trades--China--History--To 1500--Sources. I. Title.DS744.2.K34 2012931’.02--dc232012032817Copyright 2012 by the Regents of the University of California.Printed in the United States of America.All rights reserved.Front cover: An oracle bone on an ox scapula. Heji 6172. From Guo Moruo 郭沫若, ed., Hu Houxuan 胡厚宣, ed. in chief, Jiaguwen heji 甲骨文合集, 13 vols.(Zhonghua shuju, 1978–82). For transcription, see [52AB], p. 79.

ContentsPrefaceNotes about the Sources, Citation, andTranscription Conventionsxixvii1. Introduction: The Setting12. The Work and the WorkshopsBone Working9Stone and Jade WorkingPottery15Textiles16Wood Working17Bronze Casting19Cowries: Bone and BronzeThe Emergence of WritingThe Workshops28The Products3091326273. The Artisan CorpsThe Status of the Artisans33The Duo Gong 多工34“The Many Strikers”40Summary44The Dependent Laborers of ShangA Note on Population4833464. The Zhong 眾 and the Ren 人The Status of the Workers:Slave, Free, or Dependent53The Differences Between the Zhong 眾 and the Ren 人5058

5. Punishments, Human Sacrifice, and Accompanying-in-DeathPossible Punishments63The Qiang 羌 and Duo Qiang 多羌: A Sample Case66Human Sacrifice and Accompanying-in-Death69636. Labor MobilizationThe Verbs for “Mobilize”78The Verbs for “Making an Offering”78817. Who Was Mobilized868. The Occupational Lineages929. NumbersAccuracy of the Figures99Casualties among the Zhong 眾101Casualties among the Ren 人1049710. Work Schedule of the DivinersDiscussion11610611. Leadership11912. The Work: AgricultureThe Agricultural Context125Late Shang Agriculture126The Powers and the Weather129Agricultural Tools131The Yi 邑 and Tian 田132The Peasantry and the Population135Dynastic Agriculture136The Ritual Dimension152Opening Up New Land161The Use of Fire166Irrigation168Conclusions17312413. The Work: WarfareLeadership in Warfare174Army Organization179Penetration184Horse-chariot Units and the Shang ArmyShang Weapons189Shang Military History190174187

14. The Work: Hunting19415. The Work: ConstructionWall Construction200Rammed-Earth Construction203Settlements and Buildings204Temples and Other Buildings205Drainage208Royal and Other Tombs21020016. Some Elements of Ritual Concern21417. The Role of Geopolitics and CultureAncestor Worship220Other Demands for Work226The Role of Writing230The Creation of the Ancestors23222018. The Legacies236FigureTables244246Appendix 1. Inscription Glosses250Appendix 2. Glossary of Shang Terms and Phrases275Bibliography A. Abbreviations for the Oracle-Bone Collectionsand Other Reference Works368Bibliography B. Other Works Cited373Key to the Inscriptions Translated483Index488

PrefaceEgyptian, by contrast, ultimately gave rise to all historically knownscripts of the modern world, save those of East Asia. . . . China is, in otherwords, one of only two civilizations in the history of mankind to haveinvented ex nihilo a script that has endured down to the present day,and thus to have influenced the course of human history in regard to themost fundamental feature of historical civilization itself, the use of writing. (Boltz 1999:123)The present work deals with the Shang 商 dynasty (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.) inNorth China, the first to leave written records, and its efforts—evidentlywith great success—which focused on the artisan corps, labor mobilization, farming, warfare, hunting, building, leadership, and culture thatmade it all possible. My introduction to the subject of Shang labor mobilization—apart from the obligatory graduate student brush with KarlAugust Wittfogel’s work—came about quite accidentally in a Tokyo 東京bookstore in mid-December 1967. My wife, Vannie, and I* had just spenttwo-plus years in Taipei 臺北 and were then spending six weeks in Japanbefore I returned to Columbia University to write my dissertation on labormobilization in the Eastern Zhou 東周 (770–221 B.C.). When I asked whatthe bookstores had on ancient China, one of the clerks showed me ShimaKunio’s 島邦男 concordance, Inkyo bokuji sōrui 殷墟卜辭綜類 (A comprehensive compilation of divinations from the waste of Yin), whose first edition had been published in November 1967. I was not then working in theShang. I didn’t read oracle-bone inscriptions. So I merely flipped it open,glanced at the first page, and moved on to other volumes.The memory of that first page, however, remained lodged in my mind.I had evidently had the good sense to realize that it transcribed a series ofinscriptions that dealt with the “raising” of men. Indeed, had I been ableto read the first inscription that Shima transcribed (presented below atinscription number [52AB]) I would have found: “In the present season,*. The name Keightley is pronounced “Keetly,” not “Kitely”: Yorkshire, not Germanic.

xiiWorking for His MajestyHis Majesty should raise men, five thousand (of them), and march to regulate the Tufang, (for We) will receive abundant assistance.” Almost a yearpassed. I thought I should write a preface on the Shang background. Themoment I began to study the oracle-bone inscriptions I realized they contained a mine of information. And before I knew it, the focus of my dissertation was shifting from the Eastern Zhou to the Shang and Western Zhou西周 (1045–771 B.C.) (Keightley 1969). I immediately contacted the Tokyobookstore and ordered a copy of Shima’s invaluable concordance, whicharrived in New York in October 1968, and which opened up the Shanginscriptions to me, as it did to all scholars, in ways that permitted Shanghistory to be studied in a systematic way.To Chao Lin 趙林, a student of the Academia Sinica in 1968, who firstguided my early steps in the oracle bones, I owe a substantial debt. Myfirst publication (Keightley 1969a) was a review of Shima Kunio’s contribution, and I dedicated my first book (Keightley 1978) to him.1 Since I waslargely self-taught in oracle-bone studies, I suspect that I might never havebeen encouraged to focus on labor mobilization in the Shang had I notboth stumbled across Shima’s volume in that Tokyo bookstore, and hadI not flipped it open to that crucial first page. As the Shang would haveappreciated, luck, or perhaps ancestral guidance, plays a role.I have devoted works to the study of the sources (Keightley 1978, 1994,1999b, 1999e); the origins of Chinese civilization (1983, 1987a); the Shangenvironment (1999a); the Shang in general (1999b, 2000); Shang religion(1978a, 1984, 1985, 1998, 2004) and divination (1988, 1999d, 2001, 2006a,2008); the origins of Chinese writing (1989a, 2006); comparisons with theGreeks (1993); and numerous reviews (e.g., 1973, 1982, 1982a, 1990, 1997).(I cite only works that bear upon the present endeavor.) But I have keptmy 1969 dissertation—never before published—much in mind over theintervening forty-plus years. My dissertation focused in part on the activities of the zhong 眾 and ren 人; they still play a central role in the pages thatfollow. But I had subsequently found it necessary to treat the dependentlaborers of Shang in their full administrative and cultural context.2 I hadtranslated 102 Shang oracle bones in the dissertation; the present workhas 341 of them, often with several charges on the bone or shell (I estimateabout 535 charges).This book deals with oracle-bone inscriptions of the Late Shang dynasty,covering the period from Wu Ding 武丁 (ca. ?–1189 B.C.) to Di Xin 帝辛(ca. 1086–1045 B.C.). Wu Ding presumably reigned for more than twentyyears (Keightley 1978:175–76), but we do not have a firm grip on the year1. One appreciation of Shima’s book is at Wang Yuxin and Yang Shengnan 1999:404–06.2. For an introduction, in English, to the oracle bones, see, among many others: Creel 1937:21–26, 185–96; 1938:1–16; Keightley 1978; 1990; 1997; 1997a; 1999e; 2001; Rawson 1980:55–57;Takashima 1988–89; Wilkinson 2000:395–406.

Notes about the Sources, Citation, andTranscription ConventionsOne copy of the oracle-bone script and its modern transcription may befound in Yao Xiaosui 姚孝遂 and Xiao Ding 肖丁, eds., Yinxu jiagu kecimoshi zongji 殷墟甲骨刻辭摹釋總集 (1988), abbreviated as MZ (reviewedby Keightley 1997:507–08).The main source for the oracle bones is Guo Moruo 郭沫若, ed., HuHouxuan 胡厚宣, ed. in chief, Jiaguwen heji 甲骨文合集 (13 vols., 1978–82,abbreviated as Heji (reviewed in Keightley 1990:39–51). A consultation ofHu Houxuan et al., Jiaguwen Heji cailiao laiyuanbiao 甲骨文合集材料來源表 (vol. 2, 1999), will refer you to the original publication sources—from1903 to 1979—with more potential glosses. I also refer frequently to HuHouxuan et al., Jiaguwen Heji shiwen 甲骨文合集釋文 (1999) for the modern characters, abbreviating it as Heshi. In addition to the Heji, which contains 41,956 oracle-bone inscriptions, Peng Bangjiong 彭邦炯 et al., Jiaguwen Heji: Bubian 甲骨文合集: 補編 (1999), contains 13,450 more pieces; Iwill cite this as Hebu 合補.1 I also refer to Cao Jinyan 曹錦炎 and ShenJianhua 沈建華, Jiaguwen xiaoshi zongji 甲骨文校釋總集 (2006; abbreviated as JGXS) and to varied computer databases, in particular CHANT(Chinese Ancient Texts) (and see Shen Jianhua and Cao Jinyan 2001). Allof these must be considered.2I also cite Hsü Chin-hsiung, Oracle Bones from the White and Other Collections (1979) and Xiaotun nandi jiagu 小屯南地甲骨 (1980, 1983) (reviewedin Keightley 1990:51–59), both of which appear in MZ and Yao Xiaosuiand Xiao Ding, eds., Yinxu jiagu keci leizuan 殷墟甲骨刻辭類纂 (abbreviated as Y; reviewed in Keightley 1997:507–13). I also cite, but rarely, a variety of other collections in Bibliography A.1. “Since the first discovery of oracle bone inscriptions in 1899, more than 160,000inscribed pieces have been unearthed” (Lu Liancheng and Yan Wenming 2005:166).2. Cai Zhemao (1999:115–45) gives a list of nearly one thousand of the inscriptions thatappear twice in Heji. Also see Hu Houxuan (1991); Song Zhenhao (ed., 1999)—which lists10,946 bibliographic entries on the jiaguwen; and Wilkinson (2000:395–406).

xviiiWorking for His MajestyA substantial portion of the book is devoted to “Inscription Glosses”(Appendix 1) and “Glossary of Shang Terms and Phrases” (Appendix 2).The meaning of the Shang words is by no means always clear—our firstChinese dictionaries, the Er Ya 爾鴉 and Shuowen jiezi 說文解字, have beendated to a millennium or more later—and scholars have frequently disagreed about their interpretation (see Serruys 1974:12–13). The “Glosses”and “Glossary” provide an introduction to the interpretative issues andalert the reader to the uncertain nature of some of the readings that I haveadopted. They are intended to be honest accounts of my thinking, ratherthan assertive refutation of the thought of others. They leave grounds fordisagreement and invite readers to form their own conclusions.A word should be said about the periodization.3 Archaeologically, Iassign the finds from Erlitou 二里頭 and Yanshi 偃師 to the pre-Shangperiod;4 I assign Erligang 二里崗 and Zhengzhou 鄭州 to the Early Shang;5I assign Huanbei 洹北 to the Middle Shang;6 and I assign Xiaotun 小屯 (orAnyang 安陽) to the Late Shang.7I divide the finds from the sites into “Yinxu I” (Pan Geng 盤庚 [ca. 1300B.C.], Xiao Xin 小辛, Xiao Yi 小乙, and early Wu Ding 武丁); “Yinxu II”(late Wu Ding, Zu Geng 祖庚, Zu Jia 祖甲); “Yinxu III” (Lin Xin 廩辛 toWen Wu Ding 文武丁); and “Yinxu IV” (Di Yi 帝乙 and Di Xin 帝辛 [to1045 B.C.]).8 For the oracle-bone inscriptions, I use the five-period datingof Dong Zuobin (1945),9 dating the periods from Period “I” (Wu Ding)—the diviner Bin 賓, Que 㱿, etc.—till Period “V” (Di Xin). But I do not follow Dong in seeing the re-emergence of the “Old School” in Period IV,a dating that was also followed by Heji. I place, rather, the Shi 𠂤 -groupand Li 歷-group in the two Periods of I and II.10 Among other problems,3. Shaughnessy (1999:25) provides a chronology of the last nine Shang kings. Several articles of the Xia-Shang-Zhou chronology project (in English) have appeared in the Journal ofEast Asian Archaeology: Li Xueqin 2002; Nivison 2002; Zhang Changshou 2002; Zhang Peiyu2002. See too Nivison 1982–83; 1993; Pankenier 1981–82; 1995.4. Li Liu and Xingcan Chen 2003:26–101;

Late Shang Agriculture 126 The Powers and the Weather 129 Agricultural Tools 131 The Yi 邑 and Tian 田 132 The Peasantry and the Population 135 Dynastic Agriculture 136 The Ritual Dimension 152 Opening Up New Land 161 The Use of Fire 166 Irrigation 168 Conclusions 173 13. The Work: Warfare 174 Leadership in Warfare 174 Army Organization 179 Penetration 184 Horse-chariot Units and the Shang .