Transcription

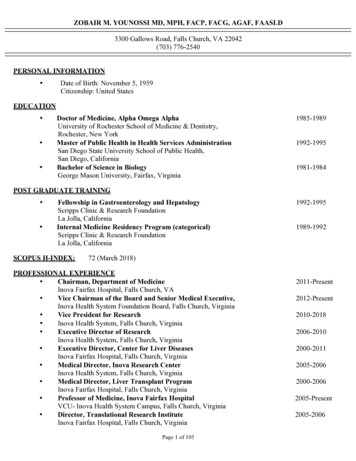

MissouriHepatitis CElimination PlanShow Me the Cure2022-26

Prepared by:Office of EpidemiologyJasmin Wright, Viral Hepatitis Associate EpidemiologistMissouri Department of Health and Senior ServicesBureau of HIV, STD, and Hepatitis:Alicia Jenkins, MSA, Bureau ChiefTara McKinney, Viral Hepatitis DirectorCassia Lawrence, Viral Hepatitis Prevention CoordinatorOffice of Public Information:Brad Bashore, Senior Multi Media SpecialistLori Buchanan, Public Relations CoordinatorContributorsMissouri Hep C Elimination Planning Committee (MO HEPC)Dean AndersonOutreach CoordinatorMissouri Telehealth Network & Show-Me ECHOCindy McDannoldBehavioral Health and SUD ProgramMissouri Primary Care AssociationVililla BroadnaxRegistered NurseSt. Louis County Department of Public HealthRachel Melson, DNP, FNP-CDirector of Outreach ServicesSwope HealthTricia CreggerMissouri Perinatal Hep B Program ManagerMissouri Department of Health and Senior ServicesJosh Moore, PharmDDirector of PharmacyMO HealthNetHeather DavenportLaboratory SupervisorMissouri State Public Health LaboratoryNatalie Torres-NegronnProgram ManagerCity of St. Louis Department of HealthLaToya DuckworthAssistant Division Director for Medical ServicesMissouri Department of CorrectionsKevin SandersViral Hepatitis CoordinatorSt. Louis County Health Department of Public HealthMichael GendernalikPrEP CoordinatorWashington University, St. Louis – Project ARKRandy SchillersVirology Unit ManagerMissouri State Public Health LaboratoryKortney GentnerState Opioid Response DirectorMissouri Department of Mental HealthChristine SewellExecutive DirectorHep C AllianceJohny GonzalezProgram Coordinator for Testing and CounselingKC Care Health CenterJulia SiebertHepatitis Nurse Case ManagerSt. Louis County Department of Public HealthMarietta HaganProject CoordinatorCoxHealthJason Stalling, MBA, CFHASection ChiefClay County Public Health CenterBrooke JarchowProgram Manager, Community HealthClay County Public Health CenterBlair Thedinger, MDAssociate Medical DirectorKC Care Health CenterClaudia JonesCommunity PlannerCity of St. Louis Department of HealthMelissa Van DyneExecutive DirectorMissouri Rural Health AssociationStaci LockhartSenior Medical Science LiaisonAbbVieNeann WedgeworthHarm Reduction CoordinatorMissouri Department of Health and Senior ServicesNicole MasseyDirector of Prevention and OutreachAIDS Project of the OzarksCole Whetstine, RNRegistered Nurse – Hepatitis CKC Care Health CenterMissouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-261Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

OurOurIncrease access to hepatitis Cprevention, testing and treatment forall Missouri residents.Create a plan to eliminate hepatitis C inMissouri by ensuring universal testing,improving health care outcomes forpeople living with hepatitis C andpreventing new infections.VisionMissionTable of Contents367141524OverviewMissouri BackgroundMissouri Data OverviewCreating the Plan – Show Me the Cure!Pillar - Goals, Activities and Workplan Pillar 1 – Access to Services Pillar 2 – Provider Development Pillar 3 – Education, Collaboration and Awareness Pillar 4 – Surveillance Pillar 5 – Policy and AdvocacyCitationsMissouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-262Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

OVERVIEWHepatitis means inflammation of the liver. There aremany reasons that inflammation can occur, but when avirus causes hepatitis, it is referenced with a letter at theend. There are three common hepatitis viruses in theUnited States: A, B and C. Each of these viruses is verydifferent in how they are transmitted and whether thereis a vaccine or cure. Below is a table outlining each of thedifferent viruses. For this elimination plan, the focus ison the hepatitis C virus (HCV), but it is essential to keepthese viruses in mind.AT A GLANCEVIRAL HEPATITISABCNoneApprox. 15%of infections75% - 85%of infectionsYesYesNoNone, it goes away on itsown within six months.Yes, but not alwayssuccessful.Yes, with direct-actingmedications, it may be cured.Blood and Body FluidsBlood to Blood(Semen and Vaginal Fluids)Symptoms of Acute Infection (if any): Fever - Fatigue - Loss of Appetite - Nausea - Vomiting - Abdominal Pain Grey-Colored Stools - Joint Pain - JaundiceTransmissionPotential for ChronicInfection:Vaccine:Treatment:Feces (fecal to oral)- VaccinationPrevention:- Wash hands after usingthe restroom- Effectively clean surfacesthat may be contaminatedwith fecesOther Notes:Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-26- Vaccination- Do not share needles ofany kind or other drugequipment.- Clean up blood spillscorrectly- Do not share razors ortoothbrushes- Do not share needlesof any kind, razors, ortoothbrushes- Do not share equipmentused for tattooing (includingink) or body piercings- Practice safe sex- Clean up blood spillscorrectly- Practice safe sexThe virus can live and be infectious in dried blood forextended periods of time.3Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Testing RecommendationsThe hepatitis C virus is one of the most significant healthproblems affecting the liver. An estimated 2.4 millionAmericans are living with HCV1. The HCV infection causesan inflammation of the liver called chronic hepatitis.This condition can progress to liver scarring, calledfibrosis, or more advanced scarring, called cirrhosis.Some individuals with cirrhosis develop liver failure orcomplications of cirrhosis, including liver cancer.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)recommends one-time HCV testing of all adults (18years and older) and all pregnant women during everypregnancy. CDC continues to recommend people withrisk factors, including people who inject drugs, be testedregularly.Signs and SymptomsMore than half of the individuals diagnosed with HCVwill develop chronic infection, while the other halfmay experience spontaneous clearance after an acuteinfection. Approximately 5 - 25% of every 100 peoplewill develop cirrhosis within 10-15 years. For individualswith cirrhosis, the rate of development of Hepatocellularcarcinoma (liver cancer) might be as high as 1 - 4% peryear1.People with newly acquired HCV infection are usuallyasymptomatic or have mild symptoms that are unlikelyto prompt a visit to a healthcare professional. Whensymptoms do occur, they can include1: TransmissionHepatitis C is a bloodborne pathogen, which istransmitted through blood-to-blood contact. Possibleexposures include1: Injection-drug use (currently the most commonmode of HCV transmission in the United States). Birth to an HCV-infected mother.Many remain asymptomatic even when their HCVinfection progresses to a chronic condition.Although less frequent, HCV can also be spread through1: PreventionSex with an HCV-infected person (an inefficientmeans of transmission, although HIV-infected menwho have sex with men [MSM] have an increasedrisk of sexual transmission). Sharing personal items contaminated with infectiousblood, such as razors or toothbrushes. Other health-care procedures that involve invasiveprocedures, such as injections (usually recognized inthe context of outbreaks). Unregulated tattooing. Receipt of donated blood, blood products, andorgans (rare in the United States since bloodscreening became available in 1992). Needle stick injuries in health care settings.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-26FeverFatigueDark urineClay-colored stoolAbdominal painLoss of appetiteNauseaVomitingJoint painJaundiceHepatitis C can be prevented by not sharing items thatcome in contact with blood. The HCV can live for days ormonths outside of the body, even if the blood is dry. HCVdoes not have a vaccine.Prevention includes the following:4 Do not share needles of any kind or other drugequipment. Do not share razors, toothbrushes, nail trimmers, orother items that could come in contact with blood. Do not share equipment used for tattooing (includingink) or body piercings. Clean up blood spills correctly. Practice safe sex.Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Hepatitis C TestingTreatmentAntibody TestTreatment is curative and easy to tolerate in 90% ofpatients. Treatment typically lasts 8-12 weeks and hasvery few side effects1.A blood test, called a Hepatitis C Antibody test(sometimes called the Anti-HCV test), is used todetermine if someone has ever been infected with HCV.The Anti-HCV test looks for antibodies to the hepatitis Cvirus. New rapid tests are now available in some settings,and the results of these tests are available in 20 minutes. Before 2014, HCV treatments were ineffective andcaused severe side effects. Given that HCV treatmenthas been simplified, many types of providers caneffectively manage HCV-infected patients, includinginternal medicine and family practice physicians, nursepractitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists.Specialists (e.g., infectious-disease physicians,gastroenterologists, pediatricians and hepatologists) maybe more appropriate when managing children with HCVand patients who have certain HCV-related sequelaeor advanced disease, including those requiring a livertransplant1. With the new medications and access toeducation resources, primary care providers can nowtreat HCV. This has opened an opportunity to make plansfor hepatitis elimination.Non-Reactive or Negative Hepatitis C Antibody testA non-reactive or negative antibody test means that theperson has not been exposed to the hepatitis C virus.However, if the person may have been exposed in thelast six months, they will need to be tested again as it cantake the body a little longer to produce the antibodies. Reactive or Positive Hepatitis C Antibody testA reactive or positive antibody test means that theperson has been infected with the hepatitis C virus atsome point in time. Once infected, these antibodieswill be present in their blood for the rest of their life,even if they clear the virus or become cured. A reactiveantibody test does not necessarily mean that the personis currently infected. A follow-up test looking for the virusin the blood (viral load) is needed.Confirmatory Testing - Diagnosing Hepatitis CIf the antibody test is reactive (positive), the individualwill need an additional test to confirm that they currentlyhave a HCV infection. Looking for viral load, this test iscalled an HCV RNA test. If the follow-up test is: Negative (or undetected) – this means they wereinfected with HCV, but the virus is not now present intheir blood. Positive – this means they currently have the virusin their blood and will need to be evaluated fortreatment.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-265Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

MISSOURI BACKGROUNDThe Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services(DHSS), Bureau of HIV, STD, and Hepatitis (BHSH), ViralHepatitis Prevention Program’s (VHPP) focus is to educateand collaborate with providers, local public healthagencies (LPHAs), substance use disorder treatmentcenters, and community-based organizations to increaseefforts related to testing, treatment and care of peoplethat are most at risk for hepatitis C Funding is providedthrough a grant from the CDC titled Integrated ViralHepatitis Surveillance and Prevention Funding for HealthDepartments. University of Missouri, Missouri Telehealth Networkhas a Show Me ECHO dedicated to HCV treatment.“The Hepatitis C ECHO empowers and supportsprimary care providers to effectively and confidentlytreat patients suffering from liver diseases.”3 Patient assistance programs are available for HCVdirect-acting viral medication. VHPP has strong partnerships with stakeholdersthroughout the state.While these programs are valuable, there is still progressneeded to eliminate HCV in Missouri.The VHPP has been in the department for many years andmodifies program priorities based on recommendationsfrom the CDC and evolving changes in HCV treatmentand populations at risk. Hepatitis A and hepatitis B (HBV)programs are located in different bureaus within DHSS.However, VHPP does provide education, training andresources on hepatitis A and B as needed.Barriers:Missouri has many strengths regarding hepatitis effortsand improvements. Funding for viral hepatitis testing, treatment, orlinkage to care is limited. The program does leverageseveral different programs and grants to increasethe importance of hepatitis testing and treatmentthrough education, awareness, and technicalassistance. The VHPP is currently unable to support HCV testingat the Missouri State Public Health Laboratory(MSPHL). The ability to conduct testing throughthe MSPHL will create reasonable testing costs,especially for underinsured or uninsured people. In the rural high burden areas, there is limited accessto treatment providers due to resources, physicianavailability, and transportation issues. Many patientsare lost to care and follow-up due to the lack ofnavigation services. This is a concern as the VHPPattempts to reduce new HCV infections. Stigma contributes to hesitancies to get tested andseek treatment.Strengths: The Missouri Viral Hepatitis Stakeholder (MVHS)workgroup was established in 2018. It comprisesrepresentatives from across the state, includingLPHAs, federally qualified health centers, communitybased organizations, hospitals and other stateagencies. This workgroup serves as an opportunity toshare resources and collaborate on projects.Hep C Alliance provides education, resources, andaccess to discounted testing to patients and providersthroughout Missouri. In August 2020, Missourians voted to expandMedicaid; therefore, Medicaid beneficiaries will nolonger be limited by age or by pregnancy/parentingstatus and access to testing and linkage to care willsignificantly improve. In July 2021, MO HealthNet launched Project HepCure. This initiative is to jump start the eliminationof HCV by making prescription MAVYRET availableto all MO HealthNet participants at no cost. Anyonewho has MO HealthNet coverage and has testedpositive for HCV is eligible for treatment2.While patient assistance programs exist for thecost of medications, there are minimal resourcesfor the cost of office visits and labs associated withtreatment for individuals that are underinsured oruninsured. People that were previously diagnosed with HCV areoften lost to care due to misinformation regardingtreatment availability, restrictions and cost.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-266Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

MISSOURI DATA OVERVIEWIn 2016, the CDC identified 13 vulnerable counties inMissouri for an HIV/HCV outbreak among People WhoUse Drugs (PWUD). Most counties are located in thestate’s southern region, specifically the southeast. Theseareas are more rural and typically have fewer resourcesor access to care. HIV and hepatitis co-infection are aconcern for Missouri, and the VHPP collaborates with HIVprograms to address HIV and hepatitis testing and linkageto care. According to the CDC, about 25% of people withHIV in the U.S. are co-infected with HCV, and about 10%are co-infected with HBV. Nearly 75% of people with HIVwho inject drugs also are infected with HCV5.Previously, HCV was highest amongst those bornbetween 1945 and 1965. Many efforts and campaignswere created to increase testing and treatment amongthis cohort. It is also recommended that people withinthis cohort receive at least one-time testing. However,individuals with high-risk behaviors are encouraged toreceive regular testing.Currently, younger people, ages 20-39, are contractingthe virus at higher rates. This is mainly related to theopioid epidemic and increased injection drug use (IDU).This population is often hard to reach for medicalinterventions and is underinsured or uninsured. Stigma isalso a factor for those that are seeking treatments.“Stigma related to hepatitis C is incredibly pervasive in our communities, particularlywhen you consider it’s association with injection drug use. This stigma often results inpeople delaying or completely avoiding testing or treatment for HCV—primarily out offear of judgement.” - Nicole Massey, AIDS Project of the OzarksMissouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-267Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

MO HEP CShow Me the CureThe VHPP collaborated with the DHSS, Section ofEpidemiology for Public Health Practice on theCooperative Agreement for Emergency Response:Public Health Crisis Response, CDC-RFA-TP18-1802grant, and provided assistance in the creation of theMissouri Vulnerability Assessment for opioid overdoseand bloodborne infections. Twenty-three counties wereidentified as vulnerable. Many of the counties identifiedas vulnerable are located in the southern region ofMissouri. This also provided a clear link between druguse and HCV, as most counties at risk for opioid overdoseoutbreaks were also at risk for bloodborne infectionsoutbreaks. Many of the same counties in the CDCassessment were in the Missouri assessment as well.Missouri Bloodborne InfectionVulnerability AssessmentThe opioid overdose and bloodborne infectionassessments were calculated separately, but severalcounties were identified as more vulnerable in bothassessments6. The complete assessment can be accessedat tyassessments-full-report-2020.pdf.Comparison of the Opioid Overdose and Bloodborne Infection Vulnerability AssessmentsOpioid OverdoseBates*BentonMariesNew MadridPolkPulaskiSt. nMississippiPhelpsRipley*St. Francois*St. Louis CityTaneyWarrenWashington*Wayne*Boodborne * indicates counties that were also identified by CDC for an HIV/HCV outbreak among PWUD.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-2688Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Missouri Statistics and DataMissouri’s communicable disease reporting rule, 19CSR 20-20.020, requires reporting acute and chronichepatitis B and C cases, perinatal hepatitis B andprenatal hepatitis B, within three days, to the localhealth authority or DHSS. Demographic information,viral status, laboratory results, and treatmentinformation are collected on standardized report formsand laboratory reports. A Viral Hepatitis AssociateEpidemiologist with the Office of Epidemiology managesthe hepatitis surveillance data stored in the MissouriHealth Surveillance Information Systems (WebSurv).Age-adjusted prevalence rates for Missouri are basedon mid-year 2020 estimates from the United StatesCensus Bureau. Limitations to data collection do exist.Limitations of the data include incomplete race/ethnicityinformation and underreporting. In 2020, Jackson County had the greatest numberof reported hepatitis C cases with 398 cases, toinclude six of the vulnerable population of thoseincarcerated. St. Louis (excluding St. Louis City)was a close second with 351 cases of hepatitis C toinclude 30 incarcerated individuals.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-26 Among males, the largest numbers of reportedhepatitis C cases were between the ages of 30-39(512)*. Among females, the largest numbers of reportedhepatitis C cases were between the ages of 30-39(318)*. The second largest number of reported hepatitis Ccases, in males, was between the ages of 50-59*, andin females, was those between the ages of 20-29*.Rapid HCV test kits are provided by BHSH and isconducted by 13 contracted HIV testing and preventionorganizations. From 2019 to 2021, these organizationsconducted 6,596 rapid antibody HCV tests with apositivity rate of 8%. These tests are conducted throughoutreach events, walk-ins, or educational presentationsin various settings including substance use disordertreatment facilities. Of the 6,596 tests conducted, 1,715indicated injection drug use as a risk factor. Individualswho indicated injection drug use had a positivity rate of23%. It should be noted that due to COVID-19, there wasa decrease in the number of tests conducted in 2020 and2021. However, even with the decrease in the number oftests conducted positivity rates remained consistent.The 2019 Epidemiologic Profiles of HIV, STDs andHepatitis can be found at re were 4,890 (to include 1,631 of those who areincarcerated) hepatitis C cases reported in Missouriin 2020, which represented an increase of 79 casesfrom the number of hepatitis C cases reported in2019.The St. Louis region had the highest rate of reportedhepatitis C cases* (43.99 per 100,000)*.*Incarcerated individuals have been excluded.Until 2021, Missouri did not receive specific funding forviral hepatitis surveillance. Since receiving this funding,DHSS has been working on reviewing and designing anepidemiologic profile specifically for Hepatitis C. 9Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

pandemic. Public health and health care testing formany programs was greatly reduced in order to prioritizeCOVID-19 response efforts. For this reason it’s likely that asmaller than usual proportion of HCV cases was identifiedduring 2020 than within the 2015-2019 timeframe.HCV risk can differ among different groups of people interms of race, geographic location and age. It is thoughtthat the opioid epidemic has shifted the distribution ofHCV over time, as injection drug use and its associatedmedical and social problems have increased in Missouriand across the U.S. Currently, risk information is rarelyreported for HCV, but demographic differences can beused to help target public health program activities todiagnose cases and ensure linkage to health care.The following chart shows a decrease in the number ofreported HCV acute and chronic cases from 2015 to 2016among unincarcerated Missourians, a plateau in thenumber of reported cases from 2016 to 2019, followed bya drop in cases to below that plateau in 2020. Also shownis a decrease in the number of reported HCV cases amongincarcerated Missourians from 2015 to 2016, a shortplateau from 2016 to 2018, followed by an increase incases during 2020.Statewide Hepatitis C Disease Burden TrendsDisease trends are best understood within the context ofhistorical events and take into account any public healthcase definition alterations that change over time. In2016, the CDC revised the case definitions for hepatitis Cvirus, both chronic and acute, which may have impactedreported HCV case numbers for 2016. Furthermore, the2020 case data visualizations provided in this sectionshould be interpreted within the context of the COVID-19The Number of Reported HCV Acute and Chronic Cases Per Year(2015-2020)Note: In 2016, the CDC revised the case definitions for hepatitis C virus, both chronic and acute, which may have impacted reportedHCV case numbers for 2016.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-2610Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Shown in the heat maps below is a comparison ofthe population density of reported HCV cases amongunincarcerated Missourians in 2015 with those reportedin 2020. Of note are the differences in geographicdistribution of reported HCV cases in 2015 comparedto 2020. In 2020 the population of reported HCV casesshifted away from metropolitan areas. Instead, thepopulation of reported HCV cases became more diffuseacross Missouri.Changes in Geographic DistributionFrom 2015 through 2020, the geographic distribution ofreported HCV cases changed in Missouri. Over time, casesbecame more evenly distributed among the programservice regions. These changes are visualized in thefollowing heat maps and chart.Total Reported HCV Acute and Chronic Cases by Region, 2015Total Reported HCV Acute and Chronic Cases by Region, 2020These changes in geographic distribution of HCV casescan also be seen in the corresponding bar chart belowcomparing 2015 reported cases to 2020 reported cases.The proportion of cases represented by incarceratedindividuals saw some changes within regions, but therewas no overall trend statewide. It is possible that changesin testing availability may have affected case reportdistribution across service regions, either from a decreasein metro areas due to COVID-19 service disruptions or anincrease in testing in rural areas.Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-26Total Reported HCV Acute and Chronic Cases by Region,(2015 and 2020)11Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Changes in Case DemographicsIn 2020, reported HCV cases were still higher in maleMissourians compared to female Missourians, althoughamongst a younger age cohort. The proportion of casesreported among younger Missourians is a shift in thedemographic profile of a typical person diagnosedwith HCV. Comparing 2015 to 2020, the median age offemales diagnosed with HCV virus decreased from 52to 48, while the median age of males diagnosed withHCV virus decreased from 47.5 to 47. Though these arenot statistically significant changes, it’s estimated thatmillennials will encompass the majority of new casediagnoses in the next few years due to the opioid crisisand the associated increase in HCV in this age group.1From 2015 through 2020, the ages of reported HCV casesamong unincarcerated individuals changed in Missouri.Over time, cases became more evenly distributedamong age groups, especially for male cases. Examinedin the charts below are the age and sex distributionsfor unincarcerated Missourians reported to have HCVinfection during 2015 and 2020. As illustrated by the data,there was a decrease in the number of reported HCVcases from 2015 to cases reported in 2020, especially inMissourians age 50 to 59 and 60 to 69, corresponding tothe 1945 to 1965 HCV age cohort that has been shownto be at higher risk for HCV diagnosis. This is becausehepatitis C was not discovered until 1989, so manymedical procedures like blood transfusions did not screenfor hepatitis C or ensure adequate infection preventionmeasures until after that time.Total Reported HCV Acute and Chronic Cases by Age and Sex, 2015Total Reported HCV Acute and Chronic Cases by Age and Sex, 2020Rose, Michelle et al. “293. Hepatitis C is now a Millennial Disease in Response to the Opioid Crisis: A Demographic Shift in Hepatitis C Infection.”Open Forum Infectious Diseases vol. 6,Suppl 2 S159. 23 Oct. 2019, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz360.3681Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-2612Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Changes in Risk Among Racial and Ethnic GroupsRacial Disparities in HCV Infection Risk, 2015Racial and ethnic disparities among HCV reported inunincarcerated Missourians during 2015 and 2020are presented below. In 2015, Black Missourians weresignificantly more likely to have a reported HCV infectionin comparison to white Missourians. Case rates forHCV infection among other reported race groups wereunstable and excluded from the analysis. HispanicMissourians were 53% less likely to have a reported HCVinfection than non-Hispanic Missourians.In 2020, the risk profile among racial and ethnic groupsin Missouri changed in comparison to 2015. As was seenin 2015, in 2020 Black Missourians were still significantlymore likely to have a reported HCV infection comparedto white Missourians. However, the difference in HCV riskbetween the two race groups decreased by 69%. HCV caserates in 2020 among other reported race groups wereunstable and excluded from the analysis. When ethnicitydifferences were examined, there was also no longer asignificant difference in HCV risk between Hispanic andnon-Hispanic Missourians, meaning that the differencein HCV risk between these two groups seen in 2015disappeared by 2020.Ethnic Disparities in HCV Infection Risk, 2015While the opioid crisis may explain some of the changesseen in this analysis, it’s possible that HCV testing accessmay have become more or less equitable from 2015-2020.These changes, along with age and geographic distributionof HCV cases, will be closely monitored in the comingyears to help inform testing and treatment policy changesthat will end the HCV epidemic.1Missouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-26Racial Disparities in HCV Infection Risk, 202013Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

CREATING THE PLAN - SHOW ME THE CUREThe Missouri Viral Hepatitis Stakeholder (MVHS)workgroup was established in 2018. It is comprised ofrepresentatives from across the state, including LPHAs,FQHCs, community-based organizations, hospitals andother state agencies.(SWOT) assessment was completed. This allowedmembers to identify what Missouri needed to focuson for this plan. The committee identified five pillarsof importance. The five pillars are Access to Services;Provider Development; Education, Collaboration andAwareness; Surveillance; and Policy and Advocacy.Based on expertise indicated in the survey, memberswere assigned to a pillar subgroup. Each subgroup metin between meetings to identify each pillar’s goals,objectives and activities.Before establishing the Missouri Hepatitis C EliminationPlanning Committee (MO HEPC), DHSS surveyed currentMVHS members to identify expertise and to measureinterest in participating in the planning committee. Itwas vital to have committed members because of theaggressive timeframe for completion. From that survey,28 members were identified and agreed to volunteertheir time and expertise.An in-person meeting was held in November 2021 foreach subgroup to present the draft on their specificpillar and gain input from all members. In January 2022,the core of the plan was finalized, after review fromDHSS. The work that members contributed to this planis invaluable and would not be possible without theircommitment and determination.The first meeting was held in August 2021. During thefirst meeting, the mission and vision were established,and Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and ThreatsMissouri Hepatitis C Elimination Planning CommitteeMissouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-2614Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Pillar 1Pillar 2Pillar 3Access onandAwarenessPillar 4Pillar 5SurveillancePolicyandAdvocacyMissouri Hepatitis C Elimination Plan 2022-2615Show Me the Cure health.mo.gov/MOHEPC

Access to S

Jasmin Wright, Viral Hepatitis Associate Epidemiologist Office of Public Information: . Missouri State Public Health Laboratory Christine Sewell Executive Director Hep C Alliance Julia Siebert Hepatitis Nurse Case Manager St. Louis County Department of Public Health Jason Stalling, MBA, CFHA Section Chief Clay County Public Health Center .