Transcription

McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64CASE STUDYOpen AccessApplying the workload indicators of staffing need(WISN) method in Namibia: challenges andimplications for human resources for health policyPamela A McQuide1*, Riitta-Liisa Kolehmainen-Aitken2 and Norbert Forster3AbstractIntroduction: As part of ongoing efforts to restructure the health sector and improve health care quality, theMinistry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS) in Namibia sought to update staffing norms for health facilities. Toestablish an evidence base for the new norms, the MoHSS supported the first-ever national application of theWorkload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN) method, a human resource management tool developed by the WorldHealth Organization.Application: The WISN method calculates the number of health workers per cadre, based on health facilityworkload. It provides two indicators to assess staffing: (1) the gap/excess between current and required number ofstaff, and (2) the WISN ratio, a measure of workload pressure. Namibian WISN calculations focused on four cadres(doctors, nurses, pharmacists, pharmacy assistants) and all four levels of public facilities (clinics, health centers,district hospitals, intermediate hospitals). WISN steps included establishing a task force; conducting a regional pilot;holding a national validation workshop; field verifying data; collecting, uploading, processing, and analyzing data;and providing feedback to policy-makers.Challenges: The task force faced two challenges requiring time and effort to solve: WISN software-relatedchallenges and unavailability of some data at the national level.Findings: WISN findings highlighted health worker shortages and inequities in their distribution. Overall, staffshortages are most profound for doctors and pharmacists. Although the country has an appropriate number ofnurses, the nurse workforce is skewed towards hospitals, which are adequately or slightly overstaffed relative tonurses’ workloads. Health centers and, in particular, clinics both have gaps between current and required number ofnurses. Inequities in nursing staff also exist between and within regions. Finally, the requirement for nurses variesgreatly between less and more busy clinics (range 1 to 7) and health centers (range 2 to 57).Policy implications: The utility of the WISN health workforce findings has prompted the MoHSS to seek approvalfor use of WISN in human resources for health policy decisions and practices. The MoHSS will focus on revisingstaffing norms; improving staffing equity across regions and facility types; ensuring an appropriate skill mix at eachlevel; and estimating workforce requirements for new cadres.Keywords: Workload Indicators of Staffing Need, WISN, Human resources, Health workforce, Workload, Namibia* Correspondence: pmcquide@intrahealth.org1IntraHealth International, Eros, PO Box 9942, Windhoek, NamibiaFull list of author information is available at the end of the article 2013 McQuide et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CreativeCommons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, andreproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64IntroductionNamibia is an upper-middle-income country characterizedby one of the greatest income inequalities in the world,with a Gini coefficient of 0.6 in 2009 to 2010 (where 1 represents complete inequality) [1,2]. Although equity hasbeen a guiding principle of the country’s primary healthcare strategy since 1990 [3], and access to health servicesin both rural and urban settings has improved, historicallyskewed resource allocation [4] affects the distribution ofhealth workers and quality of health service delivery.In recent years, public dissatisfaction with health carequality has increased considerably, alongside concernsover high maternal and child mortality. A report by thePresidential Commission of Inquiry into Namibia’s HealthService, presented to Parliament in March 2013 [5],highlighted the severe shortage of health professionals asone of the main reasons for poor health outcomes. Inaddition to health worker shortages, the country’s healthcare system also faces problems of inadequate local training capacity, uncompetitive salaries and benefits, relativelyhigh attrition rates, and low staff motivation [5].The Presidential Commission recommended promptimplementation of efforts initially launched in 2009 torestructure the Ministry of Health and Social Services(MoHSS). At that time, the Ministry formed a restructuring task force (RTF). As part of these ongoing restructuring efforts, the country’s Public Service Commission (PSC)charged the Ministry with updating the staffing norms forall operational health facilities to enable informed assessment of any proposed new staff positions. Seeking a meansof establishing an evidence base for the new staffingnorms, the MoHSS and RTF supported the application ofthe Workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN) methodin Namibia.The WISN method is a versatile human resource management tool developed and later revised by the WorldHealth Organization (WHO) [6,7]. It has been used in anumber of different settings and a variety of countries[8-14]. In the first-ever application of WISN at the national level, Namibia used the method to calculate the required number of health workers (for four cadres) in allpublic sector health facilities. In this paper, we describethe national application of the WISN method in Namibiaand explore some of the challenges encountered. We alsodescribe key findings and highlight their use in human resources for health (HRH) policy-making in Namibia.Application of WISN in NamibiaThe WISN method calculates the number of healthworkers per cadre, based on the workload of a particularhealth facility. It provides two basic indicators to assess astaffing situation: (1) the gap/excess between current andrequired number of staff and (2) the WISN ratio, a measure of workload pressure on health workers. ManagersPage 2 of 11can use WISN findings to compare staffing of similar facilities in a single administrative area (for example, healthcenters in one district) or contrast staffing levels of a particular cadre between different types of health facilitiesand different administrative areas. (For further details onthe WISN method and process, see text box).The original impetus for using the WISN method inNamibia came from the chief medical officer for theKavango region, who approached the MoHSS for permission to pilot the WISN method to estimate the region’sstaff requirements. The MoHSS gave its consent and latermade the decision to extend WISN to the national levelsince the findings from Kavango were perceived to bebeneficial to the restructuring process. With support fromIntraHealth International and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), both the Kavango andnational WISN calculations focused on four categoriesof health workers: doctors, nurses, pharmacists, andpharmacy assistants. The regional and national analysesencompassed all levels of public sector facilities, includingclinics, health centers, district hospitals, and intermediate(referral) hospitals.The Namibian WISN application consisted of the sixsteps described in the following paragraphs: establishing aWISN task force; piloting the method in Kavango region;conducting a national validation workshop; performingfield verification of the data; collecting, uploading, processing, and analyzing the data; and providing feedback tosenior MoHSS policy-makers and managers.WISN technical task forceStaff members of the MoHSS and IntraHealth set up a 12member WISN technical task force, which implementedboth the Kavango regional pilot and the national application of WISN. This task force comprised senior MoHSSleaders (Policy, Planning, Human Resources Developmentand Human Resources Management) and key regional figures including the chief medical officer, senior nurses, andhuman resources experts. The task force also was responsible for briefing members of the MoHSS RTF and otherpolicy-makers and managers.Kavango regional pilotGroups of knowledgeable doctors, nurses, and pharmacystaff came together in two-day workshops to determine themain workload components of each cadre and define activity standards. For this WISN exercise, the steering committee requested that the groups list the activities that a cadreshould be performing given adequate staffing (rather thanthose it was currently performing) in order to estimate thenumber in each cadre required to do this work. This distinction is important because severe shortages of somecadres have forced other cadres, especially nurses, to shoulder additional work and take on responsibilities outside of

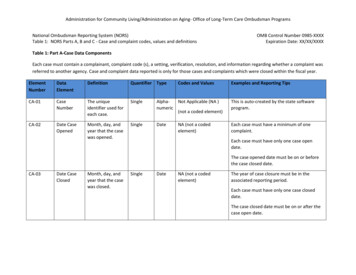

McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64their expected job descriptions. It would not be possible toimprove this situation if we included the additional activities of overburdened cadres in the WISN calculations.National validation workshopOver 100 participants attended a two-day national workshop to validate the main workload components and activity standards established by the Kavango regional pilot.Workshop participants included the four cadres (that is,senior doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and pharmacy assistants) and represented 12 of the 13 regions, key departments, and divisions of the MoHSS as well as otherrelevant partners. Participants first refined the activity listsand standards in their respective professional groups afteridentifying several missing activities and next worked toreach consensus in multiprofessional groups arranged bymanagement level and subsequent plenary. Bringing together diverse cadres engendered productive discussionsregarding staff activities and overlap.Page 3 of 11activities were then called either support or additionalactivities, depending on whether the activity was undertaken by all or only some providers of a particular cadre;a category or individual allowance was then set for eachactivity. For example, all doctors routinely do small procedures such as electrocardiograms or scans, but because they are not recorded in the HIS database thisactivity was switched from a health service activity to asupport activity. Table 1 provides an example of themain health service activities and activity standards fora nurse at a health center or clinic and defines eachworkload data item.A small group of MoHSS staff ensured availability ofrelevant data from national data sources and uploadedor entered the data to the WISN software during a twoday retreat. Although the WISN software does not currently support automatic upload of data, this was madepossible through development of a small software program to upload the data.Field verification of dataUsing routinely collected data to support analyses that inform policy and management decisions strengthens dataquality at the national level. Accordingly, the WISNprocess collected only minimal primary data and used nationally available sources of health and human resourcesinformation. Each public sector health facility reports dataon a monthly basis into several district and regional databases that are subsequently submitted into national-leveldatabases: the Health Information System database (HIS),the electronic patient management system (ePMS) forHIV/AIDS-related data, and the pharmaceutical management information systems (PMIS and EDT). To ensurecredibility of the WISN findings, the WISN task forceverified a sample of the nationally available data by comparing them with sources of primary data. Task forcemembers visited four geographically distinct regions(Erongo, Karas, Omaheke, and Omusati) to collect primary service statistics and staffing data from selectedhealth facilities. Task force members found no sizable discrepancies between the primary-level and national-leveldata from the databases. This assured us that the nationaldatabases could provide reliable workload estimates anddid not over- or underreport compared with the primarydata we collected.Data collection, upload, processing, and analysisPrior to carrying out any data entry, the WISN taskforce examined the final lists of main activities and associated activity standards elaborated at the nationalvalidation workshop. Task force members reviewedboth lists for consistency between cadres and facilitytypes and deleted several health service activities wherenational service statistics were unavailable. TheseFeedback to senior MoHSS policy-makers and managersThe WISN task force regularly briefed the MoHSS RTFon the progress of both the WISN pilot and the nationalapplication. At the request of the RTF, the WISN taskforce also made several high-level presentations to senior managers, including presentations of WISN findings at the MoHSS National Management DevelopmentForum (February 2013) and the MoHSS Strategic Management Retreat (July 2013). WISN task force membersprovided regular progress briefings to the MinisterialSteering Committee chaired by the Minister of Health.Challenges in applying the WISN methodThe WISN task force faced two main types of challengesin applying the WISN method. The first set of challengesresulted from the WISN software itself, while the secondconcerned the lack of availability of particular data itemsat the national level.Software challengesThe WHO-developed WISN software is not open source.As a result, we were not able to examine in detail how thesoftware performs its calculations. This created severalchallenges. For example, two separate reports initially provided different answers for the same calculated requirement. This was brought to WHO’s attention and latercorrected in an updated version of the software. Anothersoftware-related challenge was related to the lack of cleardirection in the WISN software manual regarding how thesoftware handles workload activities that are needed24 hours a day and 365 days a year. Through manual calculations, we determined that the software does not adjustautomatically for such activities.

ActivitiesAdmit a patientDischarge a patientDeath: last officeService standards for health centersService standards for clinicsWorkload data for the most recent fiscal year20 minutes/admissionn/aTotal admissions5 minutes/dischargen/aTotal discharges60 minutes/deathn/aTotal deathsConduct a daily ward round10 minutes/inpatientn/aTotal admissionsaRoutine nursing care30 minutes/inpatientn/aTotal admissionsGive injections10 minutes/injection10 minutes/injectionTotal injections, other than immunizationsand family planning (FP)10 minutes/lab specimen10 minutes/lab specimenTotal lab specimens taken, including ARTPerform a dried blood spot (DBS) test10 minutes/DBS test10 minutes/DBS testTotal DBS tests doneMonitor and manage normal delivery240 minutes/normal deliveryn/aTotal normal deliveriesb180 minutes/emergency delivery180 minutes/emergency deliveryTotal emergency deliveries60 minutes/delivery60 minutes/deliveryNormal forceps vacuum emergencydeliveries born before arrivalScreen and treat outpatients25 minutes/outpatient25 minutes/outpatientTotal outpatients (OPD first visits and revisits)Outpatient department (OPD) procedure25 minutes/procedure25 minutes/procedureTotal OPD proceduresTake lab specimens, including forantiretroviral therapy (ART)Monitor and manage emergency deliveryImmediate post-natal care of mother and babyTake a pap smearAntenatal care (ANC) first visitANC revisitPost-natal visitsGrowth monitoring of children20 minutes/pap smear20 minutes/pap smearTotal pap smears30 minutes/ANC first visit30 minutes/ANC first visitTotal ANC first visits20 minutes/ANC revisit20 minutes/ANC revisitTotal ANC revisits30 minutes/post-natal visit30 minutes/post-natal visitTotal post-natal visits10 minutes/childTotal children growth monitored10 minutes/immunization10 minutes/i006DmunizationTotal tetanus toxoid immunizations forwomen aged 15 to 49 years - all dosesImmunization of children under one year old10 minutes/immunization10 minutes/immunizationTotal immunizations of under-oneyear-olds - all vaccines, all doses15 minutes/FP first visit15 minutes/FP first visitTotal FP first visits10 minutes/FP revisit10 minutes/FP revisitTotal FP revisits30 minutes/HIV/AIDS revisit30 minutes/HIV/AIDS revisit80% of the total HIV/AIDS revisits plus 80%of enrolled in HIV/AIDS care and treatmentcPre-test counseling of voluntary counselingand testing (VCT) clients15 minutes/VCT client15 minutes/VCT client10% of the total VCT clients pre-test counseledPost-test counselling of VCT clients30 minutes/VCT client30 minutes/VCT client10% of the total VCT clients post-test counseled10 minutes/client10 minutes/clientTotal clients who received PMTCTFamily planning first visitFamily planning revisitIntegrated management of adult illness (IMAI)Provide prevention of mother-to-child transmission(PMTCT) counseling and testingPage 4 of 1110 minutes/childImmunization of women of reproductive ageMcQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64Table 1 Service standards for nurses in health centers and clinics, Namibia 2012

Provide TB DOTS10 minutes/DOTS visit10 minutes/DOTS visit40% of the total DOTS visitsProvide ART care and treatment15 minutes/ART revisit15 minutes/ART revisit20% of total ART revisits plus 20%of enrolled in care and treatment10 minutes/dressing10 minutes/dressingTotal dressingsDressing woundsaHealth centers do not keep data on patient days since a client stay cannot exceed 48 hours. Therefore using the number of admissions as the data source gives an estimate for daily ward rounds and routine nursingcare at a health center.bClinics only provide emergency deliveries; normal deliveries should occur at hospitals and certain health centers.cSeveral activities are done by more than one cadre; the percent represents the proportion of time the specific cadre conducts that activity.ANC: antenatal care; ART: antiretroviral therapy; DBS: dried blood spot; DOTS: directly observed treatment, short-course; FP: family planning; IMAI: integrated management of adult illness; OPD: outpatient department;PMTCT: prevention of mother-to-child transmission; VCT: voluntary counseling and testing.McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64Table 1 Service standards for nurses in health centers and clinics, Namibia 2012 (Continued)Page 5 of 11

McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64Data challengesData on a few important workload components (such asthe number of major and minor operations) were available at the facility level but not at the national level. Because the task force considered those workload activitiescritical to account for the full workload of relevantcadres, the team collected the missing data directly fromhospital theater registers. Additionally, the number ofpatient days is an important indicator of workload; because the HIS database only inputs the number of patient discharges, patient days had to be calculated fromavailable midnight census report data.WISN findingsThis paper presents key findings of particular relevanceto the use of the WISN method to inform HRH policyand practice in Namibia. Although we discuss results forother cadres as well, we particularly emphasize findingsas they relate to nurse staffing because nurses form thecountry’s biggest group of health workers (282 doctorsversus 4,251 nurses working in the public sector).The core WISN findings in Namibia can be summedup in two words: shortage and inequity. Overall, staffshortages are most profound for doctors and pharmacists. Both the intermediate and district hospitals haveonly one-third of the doctors that they require based onworkload. The shortage of pharmacists is even more severe. These serious staffing gaps are not a surprise because Namibia is still reliant on overseas recruitment forboth cadres. The local training programs have yet tograduate the first Namibian students.The WISN analysis found that only seven pharmacyassistants work in health centers, representing 11% ofthe workload-based requirement. The analysis found nopharmacy assistants at the clinic level. Even at the district hospital level, Namibia has only about a third of thepharmacy assistants that the facilities’ current workloadwould require.The WISN analysis of nurse staffing shows that on thewhole the country has an appropriate number of nurses.The nurses are, however, very inequitably distributed between the different types of facilities. The total nurseworkforce in Namibia is clearly skewed towards hospitals. This type of inequity exists, of course, in manycountries in Africa and elsewhere and represents healthprofessionals’ desire to live in urban environments offering better amenities for themselves and their families[15]. The WISN results for nurses showed that bothintermediate and district hospitals are adequately oreven slightly overstaffed relative to their workloads(Table 2), with excesses of 121 and 148 nurses at intermediate and district hospitals, respectively. However,while 18 of the 29 district hospitals have more nursesthan they require on the basis of their workload, 10Page 6 of 11actually have a shortage. At the health center level,health centers have only 85% of their required nursingstaff, representing a gap of 63 nurses. In clinics, nursingstaffing is only 77% of what is required, representing agap (210 nurses) that is over three times larger than thegap for health centers. It should be noted that the healthcenter shortage would appear greater if the facilitiesoperated around the clock as intended. However, many probably most - health centers operate only during thedaytime due to insufficient staff.Considerable inequity exists between and within regions. At the health center level, for example, Ohangwenaregion had no nurses in its only health center though calculations showed that it required 21 (Table 3). Accordingto the WISN ratio (a proxy measure for workload stress),health center nurses in Omusati region are under thegreatest workload stress (WISN ratio of 0.13), while thosein Karas region experience the least (WISN ratio of 2.46).Expressing these WISN ratios another way, health centersin Karas have 246% of their nurse requirement, whileOmusati health centers have only 13%. The WISN methodalso makes it possible to analyze staffing equity betweenhealth centers in one region (provided the region hasmore than one health center) or between clinics. InOshana region, for example, two of the five health centershave excess nursing staff. The best staffed center has 160%of its required staffing, while the three understaffed oneshave only about 40% of their requirement. Regional variation also can be illustrated by ranking regions by the sizeof the gap or excess in their required staffing for specificfacility types and cadres. For example, Table 4 shows thatthe first four regions account for 84% of the total nursestaffing gap (177/210 nurses) at the clinic level.The analysis of WISN findings demonstrates thatworkloads can vary widely within the same health facilitytype. Moreover, several clinics cope with workloads thatare higher than some health centers. In response tothese variable workloads, the workload-based requirement for nurses in the 278 clinics ranges from less thanone nurse per clinic to over 17. In the 38 health centers,the range is from a little over two nurses required in lessbusy centers to over 57 in the busiest.Using the WISN findings to inform HRH policyNamibia’s vast distances and relatively low populationdensities create considerable challenges for MoHSS efforts to balance health care equity, efficiency, and quality. Furthermore, the political pressure for enhancedquality has risen in the aftermath of the recommendations of the Presidential Commission of Inquiry. Theevidence-based WISN results provide important information for the MoHSS as it seeks to improve qualitywithout losing sight of other considerations.

McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64Page 7 of 11Table 2 Overall nurse staffing by type of health facility, Namibia 2012Type of health facilityNumber ofhealth facilitiesCurrent numberof nursesRequired numberof nursesGap/excess% of requirementIntermediate hospitals51,6211,500121108%District hospitals291,5421,393148111%Health centers38363426 6385%Clinics278693903 21077%Total3504,2194,223 4100%The utility of the health workforce findings generatedby the national application of the WISN method hasprompted the MoHSS to seek cabinet approval for thewider use of WISN in HRH policy decisions and practices. In the short term, the Ministry will focus its effortson three key areas: revising staffing norms; improvingstaffing equity across regions and types of facilities; andensuring an appropriate skill mix at each level, includingestimating workforce requirements for new cadres. At alater stage, the MoHSS intends to use the WISN methodto model future staff requirements based on differentassumptions about workloads and other key factors suchas training outputs, changing demographics and diseaseprofiles, and staff turnover.Although no official guidelines exist about how often torerun the WISN calculations, we recommend runningnew WISN estimates every two to three years, dependingon the budget cycle. The workload components should bereassessed every five or six years to ensure that they continue to reflect current activities and the standards forcompleting those activities. If health systems add newcadres or implement task-sharing, the WISN methodshould be used to estimate the new workload for thosespecific cadres.Revising staffing normsNamibia’s PSC requires a detailed facility-level proposal onstaffing norms to approve staff positions in public sectorfacilities. However, the current staffing norms in Namibia,as in most countries in the region, are not related to theworkload requirements of a specific facility. Rather, theyare based on a set number of staff by cadre according tothe type of health facility. The WISN findings can be usedin different ways to define more appropriate staffingnorms. Although one approach might be to use the averagestaff requirement as the new staffing norm, the WISN findings demonstrate that health centers and clinics inNamibia vary widely in their workloads. This implies thattwo types of clinics would require two different staffingnorms: a small clinic might require only one or two nurseswhereas a large clinic with a heavy workload could requireup to 17. Another approach to setting staffing norms is tobase the number of approved posts for a given facility onthe WISN calculations of the most recent year’s workloaddata for that facility. However, this approach ignores staffing requirements for services that the facility should be,but currently is not, delivering due to staff shortages.Therefore, the MoHSS will recommend to the PSC an approach for setting the new staffing norms that integratesTable 3 Equity between regions in health center (HC) nurse staffing, ranked by WISN ratio, Namibia 2012RegionNumber of HCsCurrent # of nursesRequired # of nursesGap/excess of nursesWISN ratio for nursesOhangwena1021 210.00Omusati7861 530.13Otjozondjupa31625 90.65Caprivi31116 50.70Khomas25173 220.70Oshana57390 170.81Omaheke167 26 630.85

McQuide et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, /11/1/64Page 8 of 11Table 4 Equity between regions: clinic staffing by nursesranked by the gap/excess, Namibia 2012RegionNumberof clinicsCurrent #of nursesRequired #of nursesGap/excessWISNratioOhangwena30105158 530.66Kavango4883130 470.64Kunene241355 420.24Omusati3984119 350.71Oshikoto205272 200.72Omaheke122439 150.61Erongo175772 150.79Otjozondjupa164256 140.75Oshana112335 120.67Hardap123035 50.87Karas144749 20.97Caprivi267355181.33Khomas96030302.02278693903 2100.77Totaltwo important considerations not previously addressed:the skill mix of cadres required to provide the minimumservice package for a given facility type, and the workloadpressure on the staff.Equity in staffing in relation to workloadsIt is possible to sort WISN findings by type of facility andcadre and easily identify the facilities most in need of additional staff. By pinpointing the health facilities with thehighest workload pressure and improving their staffing,the MoHSS expects to see improved quality of care. It alsoplans to make immediate improvements in nurse staffingin health facilities falling below an identified cut-off point(a WISN ratio of 0.6 or less, meaning 60% or less of required staffing).Staffing can be improved both by creating new postsand transferring existing staff. The process of staff transfers remains centralized through the PSC. A transferrequires a vacant staff post in the receiving facility, necessary budgetary provision for the post, and the consent ofthe individual to be transferred. WISN findings can beused to advocate for transfers (and, where necessary, newposts) that would greatly improve staffing equity in a region. Using the example of Karas region, Table 5 showshow the WISN findings could be used to identify transferoptions to alleviate workload pressure on nurses in someclinics and address overstaffing in others. The transferswould address nurse understaffing in the Berseba, DaanViljoen, Oranjemund, and Rosh Pinah clinics (which currently have only about a third to

staffing situation: (1) the gap/excess between current and required number of staff and (2) the WISN ratio, a meas-ure of workload pressure on health workers. Managers can use WISN findings to compare staffing of similar facil-ities in a single administrative area (for example, health centers in one district) or contrast staffing levels of a par-