Transcription

ANNUAL REVIEW ofNURSING EDUCATIONVolume 5, 2007Challenges and New Directionsin Nursing Education

EDITORMarilyn H. Oermann, PhD, RN, FAANProfessor, College of NursingWayne State UniversityDetroit, MichiganASSOCIATE EDITORKathleen T. Heinrich, PhD, RNPrincipal, KTH ConsultingGuilford, ConnecticutEDITORIAL BOARDDiane M. Billings, EdD, RN, FAANSuzanne P. Smith, EdD, RN, FAANChancellor’s Professor of NursingIndiana University School of NursingIndianapolis, IndianaEditor-in-Chief, Journal of NursingAdministration & Nurse EducatorBradenton, FloridaPeggy L. Chinn, PhD, RN, FAANProfessor Emerita of NursingUniversity of ConnecticutEditor, Advances in Nursing ScienceEmeryville, CaliforniaHelen J. Streubert Speziale, EdD, RNAssociate Vice President of AcademicAffairsCollege MisericordiaDallas, PennsylvaniaElaine Mohn-Brown, EdD, RNProfessor, ADN ProgramChemeketa Community CollegeSalem, OregonRichard L. Pullen, Jr., EdD, RNAssistant Director of Associate DegreeNursing ProgramProfessor of NursingAmarillo CollegeAmarillo, TexasChristine A. Tanner, PhD, RNYoumans-Spaulding DistinguishedProfessorOregon Health and Sciences UniversityEditor, Journal of Nursing EducationPortland, Oregon

ANNUAL REVIEW ofNURSING EDUCATIONVolume 5, 2007Challenges and New Directionsin Nursing EducationMarilyn H. Oermann, PhD, RN, FAAN, EditorKathleen T. Heinrich, PhD, RN, Associate EditorAnnual ReviewofNURSINGEDUCATION

To purchase copies of other volumes of the Annual Review of Nursing Education at 10%off the list price, go to www.springerpub.com/ARNE.c 2007 Springer Publishing Company, LLCCopyright All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, ortransmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Springer Publishing Company,LLC.Springer Publishing Company, LLC11 West 42nd Street, 15th FloorNew York, NY 10036-8002www.springerpub.com07 08 09 10/5 4 3 2 1ISBN-0-8261-02395ISSN-1542-412XANNUAL REVIEW OF NURSING EDUCATION is indexed in Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.Printed in the United States of America by Bang Printing.

This volume is dedicated to the memory of Jo-Ann L. Rossitto, DNSc, RN(1951–2006) who served as an editorial board member for the AnnualReview of Nursing Education (ARNE) since its inception. Energetic,loyal, and committed, Jo-Ann’s support for the scholarship of teachingand learning extended far beyond her ARNE responsibilities. The Deanand Director of Nursing Education at San Diego City College, Jo-Anninspired student and faculty colleagues to pursue educational and professional opportunities. While our scholarly pursuits were enriched byJo-Ann’s generosity in life, her legacy is a challenge to educate, lead,and mentor nurse-scholars by example.

This page intentionally left blank

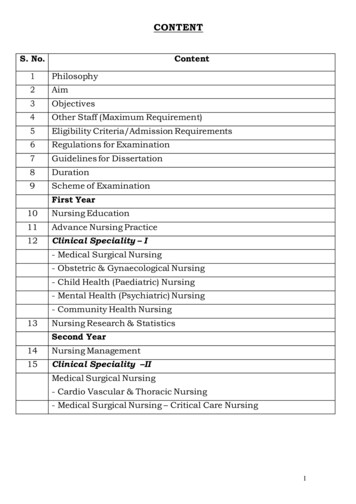

ContentsContributorsxiPrefacexvPart I: Clinical Nursing Education: New Directions inAssessment and Clinical Experiences for Students1Standardized Patients in Nursing EducationLOUISE SHERMAN JENKINS AND KATHY SCHAIVONE32A Multidimensional Strategy for Teaching CulturalCompetence: Spotlight on an Innovative Field TripExperienceMARIANNE R. JEFFREYS, LENORE BERTONE,JO-ANN DOUGLAS, VIVIEN LI, AND SARA NEWMAN253Providing Time Out: A Unique Service Learning ClinicalExperienceJAYNE KENDLE AND LINDA H. ZOELLER534Registered Nurses Mentoring Baccalaureate NursingStudents: Instrument Development and PreliminaryTestingMARY-ANNE ANDRUSYSZYN, CARROLL L. IWASIW,DOLLY GOLDENBERG, CATHY MAWDSLEY,BARBARA SINCLAIR, CHARLENE BEYNON, CATHY PARSONS,KRISTEN LETHBRIDGE, AND RICHARD BOOTH77Part II: Challenges Faced by Nurse Educators5Managing Difficult Student Situations: Lessons LearnedSUSAN LUPARELL101vii

viiiCONTENTS6Investigating Women Nurse Academics’ Experiences inUniversities: The Importance of Hope, Optimism, andCareer Resilience for Workplace SatisfactionNEL GLASS1117From Dancing With Hurricanes to Regaining OurBalance: A New NormalGWEN LEIGH, JILL LAROUSSINI, SUDHA C. PATEL,AND ARDITH L. SUDDUTH1378The Ultimate Challenge: Three Situations Call AmericanNurses to Think and Act GloballyRUTH NEESE, GENE MAJKA, AND GENEIVA G. TENNANT1539Using Benchmarking for Continuous QualityImprovement in Nursing EducationDIANE M. BILLINGS173Part III: Enhancing Learning and Student DevelopmentThrough Technology and Assessment10Student Support Services for Distance EducationStudents in Nursing ProgramsRAMONA NELSON18311A Focus on Older Adults: From Online to CD-ROMLINDA FELVER AND CATHERINE VAN SON20712Enriching Student Learning and Enhancing TeachingThrough a Course Management SystemLINDA M. GOODFELLOW23113ePortfolios in Nursing Education: Not Your Mother’sResumeJANICE M. JONES, KAY SACKETT, W. SCOTT ERDLEY,AND JOHN B. BLYTH24514“How Can I Fail the NCLEX-RN With a 3.5 GPA?”:Approaches to Help This Unexpected High-RiskGroupPAULETTE DEMASKE ROLLANT259

CONTENTSixIndex275Contents of Volume 1287Contents of Volume 2289Contents of Volume 3291Contents of Volume 4295

This page intentionally left blank

ContributorsMary-Anne Andrusyszyn,EdD, RNAssociate ProfessorSchool of NursingFaculty of Health SciencesUniversity of Western OntarioLondon, Ontario, CanadaJohn B. Blyth, MBA, MISEducation Specialist and WebDeveloperSchool of NursingUniversity at Buffalo, The StateUniversity of New YorkBuffalo, New YorkLenore Bertone, BS, RNNurse TherapistSouth Beach Psychiatric CenterStaten Island, New YorkRichard Booth, MScN(c), RNResearch AssistantSchool of NursingFaculty of Health SciencesUniversity of Western OntarioLondon, Ontario, CanadaCharlene Beynon, MScN, RNDirectorResearch Education Evaluation &Development ServicesMiddlesex-London Health UnitLondon, Ontario, CanadaDiane M. Billings, EdD, RN,FAANChancellor’s Professor of NursingIndiana University School ofNursingIndianapolis, IndianaJo-Ann Douglas, BS, RNStaff NurseBeth Israel Medical CenterNew York, New YorkW. Scott Erdley, DNS, RNClinical Associate ProfessorSchool of NursingUniversity at Buffalo, The StateUniversity of New YorkBuffalo, New Yorkxi

xiiCONTRIBUTORSLinda Felver, PhD, RNAssociate Professor and Director,Older Adult Focus ProjectSchool of NursingOregon Health & ScienceUniversityPortland, OregonMarianne R. Jeffreys, EdD, RNProfessor, NursingNursing DepartmentThe City University of New YorkCollege of Staten IslandStaten Island, New YorkNel Glass, PhD, MHPEd, BA,Dip Neuroscience Nursing,RN, FCN(NSW),FRCNAAssociate ProfessorDepartment of Nursing andHealth Care PracticesSchool of Health and HumanSciencesSouthern Cross UniversityLismore, AustraliaLouise Sherman Jenkins, PhD,RNCo-Director, Clinical Educationand Evaluation LaboratoryCo-Director, Institute forEducators in Nursing andHealth ProfessionsSchool of NursingUniversity of MarylandBaltimore, MarylandDolly Goldenberg, PhD, RNProfessor and Chair of GraduateProgramsSchool of NursingFaculty of Health SciencesUniversity of Western OntarioLondon, Ontario, CanadaLinda M. Goodfellow, PhD, RNAssociate ProfessorDuquesne University School ofNursingPittsburgh, PennsylvaniaCarroll L. Iwasiw, EdD, RNProfessorSchool of NursingFaculty of Health SciencesUniversity of Western OntarioLondon, Ontario, CanadaJanice M. Jones, PhD, RN, CNSClinical Associate ProfessorSchool of NursingUniversity at Buffalo, The StateUniversity of New YorkBuffalo, New YorkJayne Kendle, MS(N), RNCAssociate ProfessorDepartment of NursingSaint Mary’s CollegeNotre Dame, IndianaJill Laroussini, MSN, RNInstructor, College of Nursing andAllied HealthUniversity of Louisiana atLafayetteLafayette, Louisiana

CONTRIBUTORSGwen Leigh, MSN, RNInstructor, College of Nursing andAllied HealthUniversity of Louisiana atLafayetteLafayette, LouisianaKristen Lethbridge, MScN, RN,PhD(c)Research CoordinatorSchool of NursingFaculty of Health SciencesUniversity of Western OntarioLondon, Ontario, CanadaVivien Li, BS, RNStaff NurseLutheran Medical CenterBrooklyn, New YorkSusan Luparell, PhD, APRN,BCAssistant ProfessorCollege of NursingMontana StateUniversity–BozemanGreat Falls CampusGreat Falls, MontanaGene Majka, MS, RNInstructorBarry University School ofNursingMiami Shores, FloridaxiiiCathy Mawdsley, MScN, RNClinical Nurse Specialist – CriticalCareUniversity HospitalLondon, Ontario, CanadaRuth Neese, MSN, RN, CENAdjunct FacultyPalm Beach Community College –Eissey CampusPalm Beach Gardens, FloridaRamona Nelson, PhD, RN,FAANProfessor and ChairDepartment of NursingSlippery Rock UniversitySlippery Rock, PennsylvaniaSara Newman, BS, RNStaff NurseBeth Israel Medical CenterNew York, New YorkCathy Parsons, MScN, RNNursing Practice Consultant/Corporate FacilitatorSt. Joseph’s Health Care LondonLondon, Ontario, CanadaSudha C. Patel, DNS, RN, MAAssistant Professor, College ofNursing and Allied HealthUniversity of Louisiana atLafayetteLafayette, Louisiana

xivCONTRIBUTORSPaulette Demaske Rollant, PhD,RNPresident, Rollant Concepts, Inc.Test-Prep/Curriculum SpecialistNavarre Beach, FloridaKay Sackett, EdD, RNClinical Associate ProfessorSchool of NursingUniversity at Buffalo, The StateUniversity of New YorkBuffalo, New YorkKathy Schaivone, MPAManaging Director, ClinicalEducation and EvaluationLaboratorySchools of Nursing and MedicineUniversity of MarylandBaltimore, MarylandBarbara Sinclair, MScN, RNCoordinator for SimulatedClinical EducationSchool of NursingFaculty of Health SciencesUniversity of Western OntarioLondon, Ontario, CanadaArdith L. Sudduth, PhD, RN,MA, APRN-BCAssistant Professor, College ofNursing and Allied HealthUniversity of Louisiana atLafayetteLafayette, LouisianaGeneiva G. Tennant, MSN, RNCharge NurseNorth Shore Medical CenterMiami, FloridaCatherine Van Son, PhD, RNPostdoctoral Fellow andInstructorSchool of NursingOregon Health & ScienceUniversityPortland, OregonLinda H. Zoeller, PhD, APRN,BCChair and Associate ProfessorDepartment of NursingSaint Mary’s CollegeNotre Dame, Indiana

PrefaceWhen we first envisioned the Annual Review of Nursing Education (ARNE), our intent was to gather each year’s hottesttrends and cutting edge innovations into one volume. In theprocess of editing this fifth volume, we noticed that these chapters arenot only in the vanguard of nursing education, but they also reflectissues that are igniting national discourse. One of the ARNE chaptersrelates to an increase in academic incivility; the front page of The NewYork Times carried an article about legislation that has New York leadinga ”politeness trend” (Hu, 2006, p. 1). Other ARNE chapters describe thelessons nurse educators and students learned from surviving the GulfCoast hurricanes and the implications of foreign nurses’ immigrationon American nursing education, thus reflecting national and international concerns expressed often in the media. Increasingly, nurse educators’ insights and recommendations for turning teaching challengesinto opportunities can serve as an inspiration for national and globalaction.Part I of this year’s ARNE focuses on clinical nursing education.Chapters explain how to use standardized patients for clinical teachingand evaluation, share two innovative clinical experiences for students,and present the findings of the first phase of a research study on a formalmentoring program for beginning nursing students.Nurse educators face many challenges in selecting clinical sites,planning clinical learning activities, providing feedback to students, andevaluating their competencies. In chapter 1, Louise Sherman Jenkins andKathy Schaivone explain how standardized patients can help educatorsovercome some of these barriers to effective clinical teaching and evaluation. This form of simulation allows learners to practice skills witha real person in a safe and controlled environment. Having simulatedpatients trained to portray focused scenarios provides for consistency ofexperiences across learners and strengthens the reliability of the evaluation process. The authors provide sufficient detail and many examplesxv

xviPREFACEof using standardized patients in undergraduate and graduate coursesfor faculty to integrate this method in their own programs.Nurse educators are challenged to provide innovative and meaningful educational opportunities to enhance the cultural competencyof nursing students. Marianne R. Jeffreys, Lenore Bertone, Jo-AnnDouglas, Vivien Li, and Sara Newman, in chapter 2, describe a multidimensional strategy for learning and teaching cultural competence ingraduate nursing education. The strategy involves an innovative fieldtrip experience. The authors provide background information about thestrategy development, implementation, and evaluation, including anempirically supported model to guide cultural competence education—the Cultural Competence and Confidence model. Four case exemplarsdemonstrate how this strategy is applied in clinical nursing educationat the graduate level. The strategy also could be used with prelicensurestudents.Faculty teaching in undergraduate nursing programs are continuallychallenged to find meaningful clinical experiences for their students. Asstudent enrollments increase and patients’ lengths of stays decrease, thischallenge is becoming even more difficult. In chapter 3, Jayne Kendleand Linda Zoeller describe a service learning clinical experience. “TimeOut” is a pediatric respite care experience in which nursing studentsprovide respite care in the home for families with children who havespecial needs. The authors describe the benefits of this type of clinicalexperience for nursing students, guidelines for students and families,program evaluation, and outcomes of the program. Tools used to evaluatestudent learning are shared with readers.Mentoring is a voluntary partnership in which an individual withknowledge and experience, a mentor, acts as a role model for a student ornurse with less experience over an extended period of time. Mentoring isa valuable component of a nursing student’s education, but instrumentsfor assessing the characteristics and outcomes of mentoring in nursingeducation are lacking. In chapter 4, Mary-Anne Andrusyszyn, Carroll L.Iwasiw, Dolly Goldenberg, and their research team of Cathy Mawdsley,Barbara Sinclair, Charlene Beynon, Cathy Parsons, Kristen Lethbridge,and Richard Booth describe the first phase of a 3-year research studyon a formal mentoring program for beginning baccalaureate nursingstudents in Canada. The authors present how they developed and pilottested questionnaires to assess the outcomes of this mentoring programand share the mentor pretest with readers.

PREFACExviiChapters in Part II of the Annual Review address some of the challenging aspects of teaching in nursing. We begin this part with a chapterby Susan Luparell on student incivility and dealing with rude, unprofessional, and inappropriate behaviors among nursing students. The purpose of her chapter is to share some of the mistakes she made and thelessons she learned in dealing with difficult or challenging student situations as a nurse educator. Strategies to prevent and address this type ofincivility are suggested. A national survey of nursing faculty confirmedthat educators are confronted with problematic student behaviors in astonishingly high numbers. Read this chapter before encountering thesestudent behaviors in your own teaching.Issues such as competitiveness, lack of support, and workplaceviolence affect academics’ individual development and their ability toeffectively take on new educational initiatives. In chapter 6, Nel Glassshares the experiences of women nurse academics who participated in apostmodern feminist, ethnographic study that involved four countries(Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States)over an 8-year period (1997-2004). Dr. Glass explores the competitiveuniversity cultures and the hope and optimism nurse academics desperately want to maintain. Their comments reflect a new emerging discourse of nurses in academia and reveal their interpersonal experiencesof working in an academic setting.In chapter 7, four nursing faculty from The University of Louisianaat Lafayette describe their experiences during fall semester 2005 afterHurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. Gwen Leigh explains how facultymanaged their personal challenges. Jill Laroussini tells how she balanced resourcefulness and flexibility while maintaining academic commitments. Sudha C. Patel and Ardith L. Sudduth describe their strategies for helping students cope. The authors share how they respondedto a state of crisis while maintaining their educational commitments tostudents.Ruth Neese, Gene Majka, and Geneiva Tennant, in chapter 8, explore the implications of three global challenges: (1) the brain drain ofeducated professionals migrating from less to more developed countries,(2) the shortage of nursing faculty, and (3) the relationship of literacyand nursing students. The authors describe the global nature of thesechallenges for nursing education, explain how American educators areaffected by them, and offer local strategies teachers can use to meetthese global challenges. Beyond raising the consciousness of U.S. nurse

xviiiPREFACEeducators about how these global situations impinge on their professional lives, the chapter offers suggestions for action at the local, national,and international levels.Benchmarking involves identifying processes or practices fromother institutions and then using them to help an organization improvesimilar processes or practices. Benchmarking answers questions suchas: “How are we doing in comparison with other schools” and “Whois using the best practices and what can we learn from them?” DianeM. Billings, in chapter 9, reviews four types of benchmarking practices,steps that are common to most benchmarking activities, and how tointegrate benchmarking into education practices in a school of nursing.This is a good chapter to read to learn about benchmarking and its usein nursing education programs.In Part III of the ARNE, chapters shift to initiatives that enhancelearning and student development; some of these rely on new technology and others focus on guided assessment. We begin Part III witha chapter by Ramona Nelson on student support services essential in adistance education program. Distance education has become an increasingly effective tool in meeting the educational needs of students seekingdegrees in nursing. A quality, online education program requires a welldesigned curriculum as well as a wide range of student support services.Examples of key student support services include academic advising,bookstore services, financial aid, and library services. This chapter describes required online student support services, explains how theseonline services can be structured, and identifies resources for developing them.In chapter 11, Linda Felver and Catherine Van Son describe theeducational innovations they developed as part of their Older Adult Focus Project, intended to increase the ability of nurses to provide carefor older adults. As part of that project, they created materials to buildinto an existing online baccalaureate program for registered nurses. Theyalso developed a stand-alone CD-ROM to assist nursing students andnurses to increase their abilities in working with older adults and toassist educators who want to infuse older adult content into existingcourses or teach it as a separate course. They describe the development process they used, which can be adapted to other educationalsettings.Chapter 12 describes how to use a course management system(CMS) to enrich student learning and enhance teaching. A CMS is

PREFACExixa web-based “frame” through which faculty can communicate withstudents; distribute information; and facilitate the exchange of ideas,information, and resources. Linda M. Goodfellow explains how to use aCMS to manage courses taught in a school of nursing, describes innovative ways of using a CMS in both a traditional and virtual classroom,and examines the significant role of a CMS in nursing education.In chapter 13, Janice M. Jones, Kay Sackett, W. Scott Erdley, andJohn B. Blyth describe how to develop electronic portfolios (or ePortfolios). By preparing an ePortfolio, students can communicate their accomplishments and competencies, have an opportunity to work withtechnology, and demonstrate their ability to use information technologyas a tool. The authors describe their project to prepare nursing studentsfor professional practice by using a technology-based format showcasingstudents’ talents and skills in the form of ePortfolios. In addition, the advantages and disadvantages of implementing ePortfolios are discussed,and the authors share many of their tools with readers.In chapter 14, Paulette Demaske Rollant reviews the literatureon predictors and tools to identify students at risk for failure on theNCLEX-RN . In this chapter, she presents interventions she has usedover the years to successfully prepare students for the licensure examination and for taking other tests in nursing programs. These simpleinterventions can be used by faculty to prepare students to be successfultest takers in nursing programs.The goal of the ARNE is to keep you updated on innovations andnew ideas in nursing education. We hope you agree that volume 5 metthat goal. We appreciate the hard work of the authors who, as teacherscholars, so generously share their innovations for the benefit of educators everywhere. A heartfelt thanks to you for reading and recommending the Annual Review of Nursing Education to other nurse educators!Marilyn H. Oermann, EditorKathleen T. Heinrich, Associate EditorREFERENCEHu, W. (2006, April 16). “New York leads politeness trend? Get outta here.” The NewYork Times, p. 1.

This page intentionally left blank

Part IClinical Nursing Education:New Directions in Assessmentand Clinical Experiencesfor Students

This page intentionally left blank

Chapter 1Standardized Patients in Nursing EducationLouise Sherman Jenkins and Kathy SchaivoneEducators in nursing face multiple challenges in planning effectivelearning experiences and providing constructive, objective evaluation of knowledge and skills in learners. Competition for clinicalsites, increasing complexity and acuity levels of patients in clinical settings, and heightened levels of public concern about patient safety arekey among factors that mandate learners in health professions demonstrate clinical competence prior to entering the actual clinical setting.Integration of standardized patients (SPs) into learning experiences canhelp educators overcome some of these barriers to effective clinical teaching and evaluation. This sophisticated form of simulation allows learnersto practice skills with a real person in a safe and controlled environment.Having these simulated patients highly trained to portray focused scenarios allows for consistency of experiences across learners and strengthensthe reliability of the evaluation process. Consistency of clinical experience and evaluation of learners is maintained through the use of trainedSPs portraying scenarios tailored specifically to the objectives of theencounter.At the University of Maryland School of Nursing, high value isplaced on the integration of simulation into nursing curricula, beginning in the classroom, extending through laboratory experiences withvarious types of simulation incorporating various types of models ranging from simple to exceedingly complex (Morton & Rauen, 2004).This chapter was accepted on April 6, 2006.3

4CLINICAL NURSING EDUCATIONDuring the late 1990s, the University of Maryland Schools of Nursing and Medicine were using SPs on a limited basis with students. Atthat time, the SPs were contracted from another university with an established program. A thorough needs assessment conducted by bothschools indicated that the education and evaluation of students couldbe expanded and enhanced if the campus had its own SP program.Both schools agreed a strong collaborative relationship in this endeavorwould have rich mutual benefits for the learners, the two schools, andthe University of Maryland academic health science campus. In late2000, the SP program began operation as the Clinical Education andEvaluation Laboratory, a joint venture of the Schools of Nursing andMedicine.This chapter contains a definition of SPs, a general discussion ofintegrating SP encounters into nursing curricula, and background information of the origins and evolution of the SP’s role in medical andnursing education. Turning attention to the SP laboratory, the physicalenvironment is described as well as the operation of the facility. In thesection about SP encounters, we describe various models for SP encounters, explicate the role of the educator, discuss case writing andevaluation of learners, training of SPs, and the process of the actual SPencounter. Learner performance and the role of the SP, the learner, andthe educator are described. Also included is a discussion of how learnersand educators evaluate the SP encounter, and how SPs are evaluated,as well as how the SP program is evaluated. Finally, implications foreducators using SPs in nursing are discussed. Throughout the chapter,we offer general information about using SPs and our experiences in theClinical Education and Evaluation Laboratory to discuss the approachesused in these various areas.BackgroundWhat Is a Standardized Patient?The Association of Standardized Patient Educators defines a SP as “a person trained to portray a patient: This can be for instruction, assessment,or practice of communication and/or examining skills of a health careprovider” (Gliva-McConvey, 2006). Training of SPs is key and shouldresult in:

STANDARDIZED PATIENTS IN NURSING EDUCATION5.a person who has been carefully coached to simulate an actual patient soaccurately that the simulation cannot be detected by a skilled clinician. Inperforming the simulation, the SP presents the gestalt of the patient beingsimulated; not just the history, but the body language, the physical findings,and the emotional and personality characteristics as well (Barrows, 1987).Standardized patients are lay people/actors who are employed by acenter or laboratory, carefully trained to simulate a particular “case” orscript, and—in many cases—provide feedback to the learner on theirperformance.Integrating Standardized Patient Encounters Into Nursing CurriculaStandardized Patient encounters can be integrated into the curriculumfor instruction and practice of skills, to evaluate learners, for programevaluation, faculty development, and research. Standardized Patient encounters allow for repeated experiences in which the learner can attendto the critical aspects of the situation and improve performance in response to patient outcomes, feedback, or both. There are characteristicsof SP encounters that lend themselves to effective integration into nursing education.The learner is an active participant in the experience rather thana passive observer. Because these encounters take place in the safe andpredictable environment of a laboratory, errors are educational experiences rather than patient disasters. In a clinical setting, the experiencesof learners are often uneven and controlled by the availability and condition of patients. In SP encounters, the behavior, presentation, andresponses by the patient are determined by the case, and the patientsare trained to adhere to that training. The sessions are flexible in that theycan take place at the convenience of the educator and learners. Throughthis methodology, educators can do direct comparisons of learner competence and efficiently use their time by observing multiple learners inone setting. The SP evaluations are responsive to real differences in performance due to case control. Learners can receive immediate feedbackand debriefing from SPs and educators.During SP sessions in which the learner is challenged with advancedclinical management of complex patient problems, educators are able toview the continuum of a student’s ability to take a history, complete anappropriate physical examination, plan for appropriate interventions,

6CLINICAL NURSING EDUCATIONand use some basic care measures with the SP. Through the integrationof SP encounters in the curriculum, universal competencies that are thefoundation of skills needed for effective clinician—patient interactionscan be taught and assessed. Ideally, a decision to integrate SP encountersinto a course or program would occur during development of the course.Doing so allows for careful identification of cognitive, psychomotor, andaffective knowledge and skills to be specified in the learning objectives.Integrating an SP encounter(s) into the curriculum serves as a focal pointfor the development and integration of competency-based skill evaluation. Standardized Patient encounters can also be added into existingcourses and programs as an innovative teaching strategy as well as anassessment strategy. In addition, the SP encounter offers an opportunityto use knowledge and skills attained in an appropriate context.Origin and Evolution of the RoleOver 40 years ago, Dr. Howard Barrows—a neurologist wanting to betterassess the clinical skills of his students—became the “father” of simulatedpatients as he employed and trained actors who were readily availablein southern California to work with his students. Using cases of actualneurology patients as templates for the scenarios the actors would portray, a detailed script was developed to determine the exact detail ofeach case to be presented. Thus, these simulated “patients” were trainedto present the same signs, symptoms, history, emotional state, and, insome cases, physical examination findings to students.This approach allowed Dr. Barrows to present the same “patient”multiple times for his students. He could then observe each student withthe simulated patient in a safe and controlled environment and ass

Professor, ADN Program Chemeketa Community College Salem, Oregon Richard L. Pullen, Jr., EdD, RN Assistant Director of Associate Degree Nursing Program Professor of Nursing Amarillo College Amarillo, Texas Suzanne P. Smith, EdD, RN, FAAN Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Nursing Administration & Nurse Educator Bradenton, Florida Helen J. Streubert .