Transcription

B-625711/12Texas Well Owner NetworkWell Owner’s Guideto Water Supply

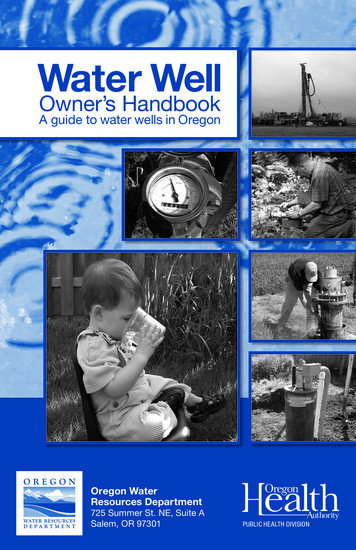

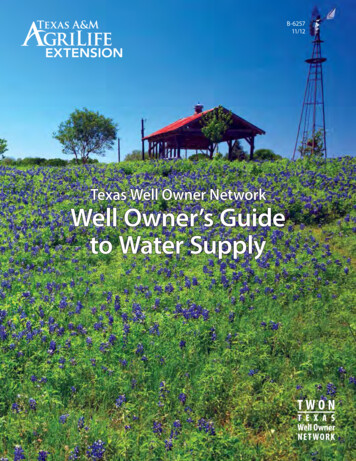

Major Aquifers of TexasMajor aquifers of RAYWHEELERDEAF ROHANSFORDOCHILTREEHUTCHINSON OSBYKINGDICKENSCOOKEARCHERBAYLORKNOXGRAYSONRED THROCKMORTONDENTONWISEYOUNGCOLLINHOPKINSHUNTMORR ISTERRYFRAN ALLASTARRANTPARKERPALO PINTORAINSUPSHURKAUFMAN VAN RISONG REGGSMITHJOHNSONRUSKNAVARROEL BYSCRANEUPTONREEVESCORYELLTOM TONSAN SABABELLJEFF NCHOIRIONNESA T RDINTRAVISGILLESPIEHAYSKERREDWARDSKENDALLVAL OGUADALUPEFORT WHARTONBRAZORIAWILSONDE DIMMITMcMULLENLA SALLEPecos ValleySeymourGulf CoastCarrizo - Wilcox (outcrop)Carrizo - Wilcox (subcrop)Hueco - Mesilla BolsonOgallalaEdwards - Trinity Plateau (outcrop)Edwards - Trinity Plateau (subcrop)Edwards BFZ (outcrop)Edwards BFZ (subcrop)Trinity (outcrop)Trinity (subcrop)CALHOUNLIVE EKENEDYSTARRRDE V E L OPMOT B AR DJIM HOGGZAPATAEENKLEBERGX A S WATJIMWELLSWILLACYHIDALGOCAMERON NOTE: Chronology by Geologic age.OUTCROP (portion of a water-bearing rock unit exposed at the land surface)SUBCROP (portion of a water-bearing rock unit existing below other rock DISCLAIMERThis map was generated by the Texas Water Development Boardusing GIS (Geographic Information System) software.No claims are made to the accuracy or completeness of theinformation shown herein nor to its suitability for a particular use.The scale and location of all mapped data are approximate.Map updated December 2006 by Mark Hayes, GISPwww.twdb.state.tx.us/groundwater

Texas Well Owner NetworkWell Owner’s Guide to Water SupplyKristine UhlmanExtension Program Specialist–Water ResourcesDiane E. BoellstorffAssistant Professor and Extension Water Resources SpecialistMark L. McFarlandProfessor and State Water Quality CoordinatorBrent ClaytonExtension Program SpecialistJohn W. SmithExtension Program SpecialistThe Texas A&M System

ContentsChapter 1. IntroductionAbout the Handbook.1About the Texas Well Owner Network.1Chapter 2. Aquifers in TexasHow Aquifers Develop.3Water Movement in Aquifers.3What Creates an Aquifer?.4Aquifer Recharge.7Chapter 3. Physiographic Provinces of Texas and Aquifer TypesHigh Plains.9Gulf Coastal Plains. 10Grand Prairie and the Edwards Plateau.11North-Central Plains.12Basin and Range.12Central Texas Uplift: The Hill Country.13Chapter 4. Watersheds and AquifersSoil Type.16Land Use.16Topography.17Aquifer Characteristics.18Chapter 5. Well Siting and ConstructionInformation about Your Well. 21Well Siting Regulations. 23Well Construction. 24How Wells Affect Aquifers: Cones of Depression. 27Well System Failure. 28Chapter 6. Water QuantityTexas Water Rights and Groundwater Ownership.31Shared Wells . 32Low-Yielding Wells. 34Options for Correcting Low-Yield Wells. 34Drought. 35Chapter 7. Water QualityDrinking Water Guidelines and Standards. 37Total Dissolved Solids. 38Hardness. 39Acidic or Alkaline Water: pH. 39Organic Matter and Hydrogen Sulfide (Rotten Egg Odor). 40Dissolved Metals, Iron, and Manganese. 40Naturally Occurring Contaminants in Texas Groundwater. 41 vTexas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water Supply

Chapter 8. Common Contaminants in Well WaterNitrate. 45Bacteria and Pathogens. 46Contaminants Produced by People. 47Emerging Contaminants. 48Chapter 9. Water Quality TestingWater Quality Testing Schedule. 51How to Sample a Drinking Water Well. 53Interpreting Water Test Results. 53Doing Your Own Testing: Water Testing Kits. 54Chapter 10. Water Treatment OptionsParticle and Microfiltration. 57Activated Carbon Filter. 58Reverse Osmosis. 58Distillation. 59Ion Exchange: Water Softening. 59Disinfection. 60Continuous Chlorination of Domestic Wells. 60Boiling. 60Emergency Disinfection. 60Chapter 11: Protecting Your Well Water QualityWell Installation and Maintenance. 63Wellhead Protection. 64Household Wastewater Management and Onsite Septic Systems. 66Plugging Abandoned Water Wells. 67Shock Chlorination of Water Wells. 68Hydraulic Fracturing. 69APPENDICESA. Agencies and Organizations: Where to Find Help. 70B. National Primary Drinking Water Standards. 72C. Water Problems: Symptoms, Tests, and Possible Sources. 78GLOSSARY. 81 viTexas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water Supply

AcknowledgmentsFunding SourcesThis guide was developed with support from a grant from the Nonpoint SourceManagement Program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The programis under the purview of the Clean Water Act Section 319, through the Texas StateSoil and Water Conservation Board, under Agreement No. 10-04.Support was also given by the National Integrated Water Quality Program of theNational Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, underAgreement No. 2008-51130-19537, also known as the Southern Region WaterResource Project.Review and DevelopmentThe authors would like to thank the following groups and individuals for their assistance:Texas State Soil and Water Conservation BoardJana LloydT. J. HeltonAaron WendtTexas Water Resources InstituteBrian VanDelistDanielle KalisekKevin WagnerTexas Groundwater Protection CommitteeAlan Cherepon, Texas Commission on Environmental QualityDavid Gunn, Texas Department of Licensing and RegistrationKathy McCormack, Texas Commission on Environmental QualityChris A. Muller, Texas Water Development BoardPeter Pope, Texas Railroad CommissionSpecial Thanks To:Pamela Casebolt, T. J. Helton, and Aaron Wendt of the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board, for theirvision and support of this new programJanick Artiola of the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science at the University of Arizona, and GaryHix of the Arizona Water Well Association, for sharing their work from the Arizona Well Owner ProgramLisa Angeles Watanabe for graphics developmentRobert Mace of the Texas Water Development Board for sharing his collection of historic photosDiane Bowen and Melissa Smith, Extension Communication Specialists, for editing and graphic designDisclaimerThe information in this publication is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products and/ortrade names are made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by theTexas A&M AgriLife Extension Service is implied. viiTexas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water Supply

1: Introduction

Chapter 1: IntroductionAbout the TexasWell Owner NetworkChapter 1: ProgramIntroductionChapter 1: IntroductionHgroundwater sources, water quality, water treatment, and well maintenance issues.ousehold well owners in Texas areresponsible for ensuring that their wellwater is safe to drink. People who drinkpolluted water can become sick and, in somecases, die. Health problems caused by contaminated well water include illnesses from bacteriasuch as E. coli, “blue baby syndrome,” and arsenicpoisoning.The Texas Well Owner Network is an educational program that aims to:Unsafe drinking water from wells is often causedby high concentrations of minerals—such asarsenic and uranium—that occur naturally acrossTexas. Well water can also be polluted by seepagefrom failed septic tanks and by synthetic compounds such as fertilizers, gasoline, and pesticides. Educate residents about water issues, with afocus on groundwater Help Texans improve their water’s quantity andquality Help residents implement community watershedprotection plans and participate in the TexasWatershed Steward programAccording to the Centers for Disease Control, upto 30 percent of U.S. households depend on private wells for drinking water. Of the water usedin Texas, roughly 60 percent is from groundwater, which is the water below the earth’s surface.Anyone who wants to learn about, improve, andprotect community water resources can participate in the Texas Well Owner Network. The network includes well owners, agricultural producers, decision makers, and community leaders.In Texas, as across the United States, the government does not routinely test household well waterto make sure it is safe to drink. The well drillermust test it for bacteria when the well is firstinstalled; thereafter, it is the well owner who isresponsible for making sure the water is safe.The Texas Well Owner Network is being offeredby the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service incooperation with the Texas State Soil and WaterConservation Board and other agencies and organizations.Our water’s quality and quantity are greatlyaffected by the way we live. If we learn about ourwater resources and understand how our activities affect them, we can help keep our water safeto drink as well as preserve, protect, and enhancethis vital resource.ReferencesAbout the HandbookThis publication was created to help Texans keeptheir well water safe to drink and use. It waswritten for the participants in the Texas WellOwner Network (TWON) and Texas residentswho depend on household wells for their drinking water. It provides information about TexasU.S. Census Bureau. Current Housing Reports,Series H150/07, American Housing Survey for theUnited States: 2007, U.S. Government PrintingOffice, Washington, DC: 20401, 2008. Availableat www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/h150-07.pdf. 1Texas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water SupplyChapter 1: ProgramIntroductionBartholomay, R. C., J. M. Carter, S. L. Qi, J. H.Squillace, and G. L. Rowe. 2007. Summary ofSelected U.S. Geological Survey Data on DomesticWell Water Quality for the CDC NEPHTP. USGSReport 2007-5213.

2: Aquifers in Texas

Chapter 2: Aquifers in Texas Consolidated (bound or cemented) rockmaterials include the granite formations of theHill Country of Central Texas and the limestone formations in the Edwards Aquifer. Inconsolidated aquifers, the water is held in thefractures and cracks of rock.In some types of sediment movements, the materials are not sorted well, such as when landslidesdeposit loose and jumbled bits of rock and sediment known as colluvium. Aquifers formed inpoorly sorted, unconsolidated materials are calledcolluvial aquifers.Chapter 2: Aquifers in Texas Unconsolidated (loose) rock materials includethe sands and gravels of river valleys. In unconsolidated aquifers, water is held in the emptyspaces (pores) between grains of clay, silt, sand,and gravel.When sediment is moved, it is often sorted intoparticles of similar sizes. For example, sand grainsdeposited by wind that form a sand dune tendto be about the same size. Fast-moving rivers cantransport gravel and large cobbles (rocks about 2½to 10 inches in diameter); in contrast, lakes andslow streams form layers of fine silt and clay at thebottom.Chapter 1: ProgramIntroductionAflowing water are said to be alluvial. Materialsmoved by wind are termed aeolian.n aquifer is an underground geologicformation that can produce (yield ortransmit) usable amounts of water to awell or spring. Aquifers may be composed of oneor a combination of materials (Fig. 1):Some sediments harden into consolidated rock ina process known as lithification. An example oflithification is when lava cools and hardens intosolid basalt. Other examples are when sedimentsare buried and squeezed under pressure to formshale, or when they are melted and metamorphosed to form granite.How Aquifers DevelopKnowing how an aquifer has developed geologically can help you understand how much waterthat a well can yield and how vulnerable it is tocontamination.These consolidated rocks can be weathered by biological, chemical, and physical processes. Weathering produces the clay, silt, sand, gravel, and otherrock fragments that compose unconsolidatedaquifers.Unconsolidated aquifers are formed when windor water moves and deposits geologic materials such as sand and gravel. Materials moved byThe transition between unconsolidated to consolidated rock can be subtle, but it is generally truethat if you can dig at the aquifer material with aspoon, the aquifer is unconsolidated.In unconsolidated aquifers, water flows throughthe interconnected pores between grains of sediment. The ratio of space to these grains is knownas primary porosity.Figure 1. Aquifers can be composed of unconsolidatedmaterials, consolidated materials, or a combination of both. 3Texas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water SupplyChapter 1: ProgramIntroductionWater Movementin Aquifers

Chapter 2: Aquifers in TexasChapter 2: Aquifers in TexasWater moves faster through anaquifer made of sand particles,which are larger (0.05 to 2 mm)than those of other types of soiland create larger pore spaces.Water flows much more slowlyaround silt and clay particles,which are smaller (less than0.05 mm) and have smaller porespaces. Small particles tend tofilter water more effectively,removing many pollutants beforethey can reach the aquifer; thelarge pollutants cannot getthrough a fine filter.Consolidated aquifers developFigure 2. A view of Texas from space showing traces of the tectonic rifts alongwhen rock breaks or fractures;the Mississippi River and Rio Grande River Valleys that formed many aquifersacross the state.the ratio between the spacesand the rock is called secondaryporosity. In a consolidated rockaquifer, secondary porosity can be increased bywhen the North AmeriDid You Know?breaking up, or fracturing, the rock. This processcan continental plateIn 1811 and 1812, theis the basis of hydraulic fracturing proceduresbegan pulling away fromlargest earthquakecarried out to increase gas, oil, and water wellEurope. Over time, thisrecorded in theoutput (see Chapter 11).expansion created thecontinental UnitedAtlantic Ocean.States occurred in arift near New Madrid,What Creates an Aquifer?As continent-sized platesMO (Fig. 3). During theof rock pull apart andearthquake, parts ofthe Mississippi Riverpush together, they gendropped by as mucherate earthquakes, formas 10 feet. Several daysmountains, and crepassed before the riverate chasms called rifts.flow stabilized.Sediment is moved anddeposited into the riftvalleys and farther downstream.As melted rock circulates deep inside the earth,it lifts, moves, and breaks up enormous plates ofrock using natural influences called tectonic forces.Did You Know?These forces cause contiToday, continental shiftnental drift, the movementis causing the Atlanticof the earth’s continents inOcean to expand byrelation to each other.about 1 inch per year.The coastal and eastern Texas aquifers were created by the geologic activity around the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, whichformed in a rift valley more than 750 millionyears ago.Over a lifetime, thisexpansion will increasethe distance betweenNew York and Londonby about 6 feet.In Texas, aquifers havebeen formed by this geologic activity in the Mississippi River Valley, theRocky Mountains, and theRio Grande River Valley (Fig. 2). The activityhad its beginnings about 200 million years ago,The Mississippi Valley continues to subside, moving sediments to form a thick delta, or alluvial 4Texas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water Supply

Chapter 2: Aquifers in TexasIn the High Plains of Texas, erosion of the RockyMountains has created very thick deposits ofsediment. Much of the High Plains and the central Great Plains of the United States is coveredwith layers of unconsolidated sediments.Figure 3. A series of earthquakes occurred in 1811 and1812 along the New Madrid fault system. Some shockswere felt as far away as Toronto, Canada.Chapter 2: Aquifers in TexasOver millions of years, subsidence and changesin sea level have caused the shoreline of the Gulfof Mexico to advance and retreat. During thatperiod, most of Texas was often covered withocean water.Chapter 1: ProgramIntroductionfan, that extends into the Gulf of Mexico. A deltais an outspread, gently sloping landform thattakes the shape of a fan. Sediment from CentralTexas has also been deposited along the easterncoast of Texas, creating wedges of sediment thatthicken in the direction of subsidence (Fig. 4).In West Texas, the Rio Grande River is in a riftvalley that began forming 35 million years agoas the southwest portion of the continental platewas pulled west. The Rio Grande Rift extendsfrom southern Colorado into Mexico, and theRio Grande River follows the depression in theland surface. In contrast to the rest of Texas, theRio Grande Valley is more arid, and there is notenough moisture to erode and transport sediment. Here, gravity moves most of the sediment(Fig. 5).Figure 4. Alluvial sediments in eastern Texas, withdeposition in the direction of the Gulf of Mexicosubsidence.Figure 5. In arid climates, gravity moves unconsolidated rock into mountain basins. 5Texas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water SupplyChapter 1: ProgramIntroductionIn some areas, the earth’scrust is stretched andbroken by faults that arenearly vertical. Large,consolidated blocks ofrock are moved verticallyto create mountain rangesand basins (broad valleys).The mountaintop can be asmuch as 10,000 feet fromthe valley basement. Thevalleys can be filled withup to 7,000 feet of gravel,sand, and silt.

Chapter 2: Aquifers in Texascore of the continental plate, to the land surface(Fig. 6).Chapter 2: Aquifers in TexasLimestone consists of calcium carbonate from theskeletal remains of ocean creatures such as coral(Fig. 7). Beds of limestone were deposited in theGulf of Mexico as the shoreline advanced andretreated over the landscape.Although limestone is a consolidated rock, it isvery soluble. When slightly acidic water movesthrough the fractures and cracks in limestone,the rock dissolves and karst landscapes develop.Figure 6. The Llano Uplift brought pink graniteconsolidated rock to the land surface. This type of granitewas used to build the state capitol in Austin.Unconsolidated rock aquifers are formed from sediment transport and deposition; consolidated rockaquifers erode and provide the source of sediment.Through time, the unconsolidated sediments maybecome compacted and eventually transition intoconsolidated rock aquifers. When the pore spacesare filled with fresh water, these aquifers becomepotential sources of drinking water.This type of natural landscape feature is calleda basin and range landform. Such landforms areprevalent across the Basin and Range Province,which is located from West Texas to California.Volcanoes in the Basin andRange Province createdigneous rock (rock madefrom molten or partly molten material) such as basalt.In parts of West Texas,consolidated aquifers haveformed in this igneous rock.In West, East, and SouthTexas, tectonic forcesstretched rock that latereroded. The sediment thatwas deposited over millionsof years eventually formedaquifers. In the LlanoUplift of Central Texas,tectonic forces broughtbasement rock, the deepFigure 7. Canyon Lake Gorge showing limestone of the Edwards Aquifer. 6Texas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water Supply

Chapter 2: Aquifers in TexasAquifer recharge can occur many miles from awell. For example, water can filter undergroundwhere the aquifer is exposed at land surface.The water can then be extracted miles from therecharge area.Aquifer RechargeWater from rain and snowfall seeps through thesoil and recharges (replenishes) the aquifer. Whenthe aquifer is recharged, the water table elevationrises; during drought, it drops (Fig. 8). The depiction of the change in water-table elevation overtime is called a hydrograph.Chapter 2: Aquifers in TexasFigure 8. A hydrograph shows the changes in water-tableelevation over time.Chapter 1: ProgramIntroductionScientists can determine how fast and how oftenan aquifer is recharged by measuring isotopes(different forms of an element) of hydrogen andoxygen as well as other elements, such as carbon,that have dissolved in the water. As precipitation passes through the atmosphere, it picks upa unique isotopic fingerprint that can be used tomeasure how long ago the water fell as precipitation. Hydrologists can then calculate the timesince the aquifer was recharged, or the age of thewater.Recharge can also occur along streams and fromlakes and reservoirs, wherever water is in contactwith the aquifer.ReferenceOnly some of the rain or snow recharges theaquifer; most of the water evaporates, is taken upby plants, or drains off the landscape into streamsand rivers. The amount of groundwater that anaquifer can hold is determined by its porosity.Scanlon, B. R., and A. Dutton, M. Sophocleous.(2003) Groundwater Recharge in Texas. TexasWater Development Board, Austin, TX.Chapter 1: ProgramIntroductionFigure 9. Flowing artesian well developed for the Port Arthur, Texas, water supply (circa 1910). 7Texas Well Owner Network: Well Owner’s Guide to Water Supply

3: Physiographic Provincesof Texas and Aquifer Types

Chapter 3: Physiographic Provinces of Texas and Aquifer TypesHigh PlainsThe provinces are described below using information from the Physiographic Map of Texas, whichwas produced in 1996 by the Bureau of Economic Geology. Also listed are the aquifer(s) ineach province as well as the predominant aquiferexpected to provide water for a domestic, household well.The High Plains of Texas (pink area of Fig. 10)forms a nearly flat plateau with an average elevation of about 3,00

jones nueces reagan bowie ward zapata lamar real nolan terry garza mills coleman ector tom green mason young falls cameron matagorda hays brown cooke j a s p e r deaf smith burnet maverick houston lavaca fisher collin moore fannin motley . ford e n robertson washing-ton aransas san patricio major aquifers of texas note: chronology by geologic .