Transcription

R E V I E W S & A N A LY S E SHandoff Communications: A Systems ApproachLea Anne Gardner, PhD, RN INTRODUCTIONSenior Patient Safety AnalystPennsylvania Patient Safety Authority Personnel at a Pennsylvania healthcare facility contacted the Pennsylvania PatientABSTRACTHandoffs are an integral part of carecoordination and the delivery of safepatient care. Effective handoffs havemultiple functions: transferring responsibility and accountability for the patient’scare and confirming the accuracy ofinformation from one healthcare workerto another and providing opportunities to catch and correct errors. InPennsylvania, facilities reported 1,565handoff-related events through thePennsylvania Patient Safety ReportingSystem (PA-PSRS) that occurred in 2014and 2015. About 60% of the handoffreports indicated discrepancies betweeninformation shared and the patient’scondition noted during or after a handoff with no description of a follow up; in40% of the event reports, a follow up inpatient care to address the discrepancywas stated. In addition, about 20% ofthe event reports stated that there wasno handoff given and in another 16%of the event reports, details about thepatient’s condition were omitted fromthe handoff. Using handoff processesthat incorporate critical thinking andreasoning skills to address patientneeds, addressing environmental distractions and communication deficits,and providing handoff training and education are strategies to improve patienthandoff communications. (Pa Patient SafAdvis 2017 Mar;14[1]:17-26)Safety Authority to learn about the types of handoff-related events reported byother facilities in the state so they could adapt and improve their handoff processes.Handoffs involve sharing patient information and often include performing a visualinspection of the patient to confirm the accuracy of information conveyed.1 Handoffcommunications coordinate patient care by passing essential information about apatient’s health status and responsibility for the patient’s care from one healthcareworker to another. They occur at change of shift (e.g., attending physicians, nursingstaff), transfer of patients from one area within a healthcare facility to another, transfers between facilities, and during shifts when staff leave the unit or area to tend toother patients or take a break. Each handoff provides opportunities to catch and correct errors.2When a handoff is successfully completed, the next person responsible for the patienthas the necessary information to inform care for that specific patient. In cases in whichinformation is incomplete or a handoff fails to occur, an incomplete understandingof a patient’s condition may contribute to inappropriate or inadequate treatment. Ina study by Tucker and Edmondson, missing or incorrect information was one of fivebroad types of healthcare problems or process failures encountered by nurses.3 Lapsesin handoffs impact all groups of healthcare clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses, alliedhealth professionals) and nonclinicians (e.g., transportation staff).Handoffs between healthcare workers occur hundreds to thousands of times eachday, creating opportunities to identify effective handoff communications. The JointCommission identified [inadequate] communication as the third most frequentlyidentified root cause for a sentinel event in 2014 and 2015.4 Good communication isa part of patient care and leadership standards.5-7 The challenge in completing a successful handoff is knowing what information is most important and how to convey theinformation in a clear and concise manner appropriate for the patient’s circumstances.For example, hospital intensive care units may adhere to handoff criteria that differfrom obstetric unit criteria. Effective handoffs require teamwork, shared practices, andshared expectations (e.g., use of handoff tools).8-10The literature is replete with articles focusing on the use of handoff tools.10-15Healthcare professionals have developed and validated a variety of handoff toolsthat provide a shared mental model to help complete a patient handoff. Examples ofsome well-known handoff tools for clinicians include SBAR (Situation, Background,Assessment, and Response) and I-PASS (Illness severity, Patient summary, Action list,Situation awareness and contingency planning, and Synthesis by receiver), and for clinical and nonclinical staff, the “ticket to ride” tool, used when transporting patients.15-18Handoff tools help clinicians gather needed information and pass it on to other healthcareworkers, but this integral part of coordinating patient care can fail.2,14,19-23 (See Table 1.)METHODSAnalysts queried the PA-PSRS database to identify handoff-related events reported byPennsylvania healthcare facilities that occurred in 2014 and 2015. The query searchedfree-text data fields of the event type “Other,” event description, and recommendations using the following keywords: handover, sign off, nursing report, shift report, off(continued on page 19)Vol. 14, No. 1—March 2017 2017 Pennsylvania Patient Safety AuthorityPennsylvania Patient Safety AdvisoryPage 17

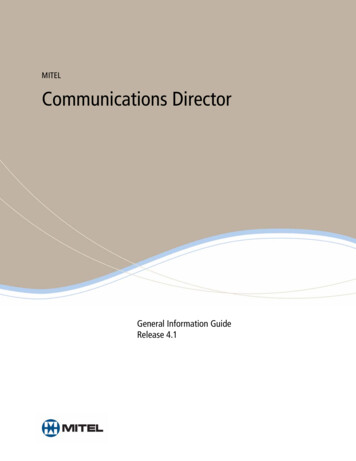

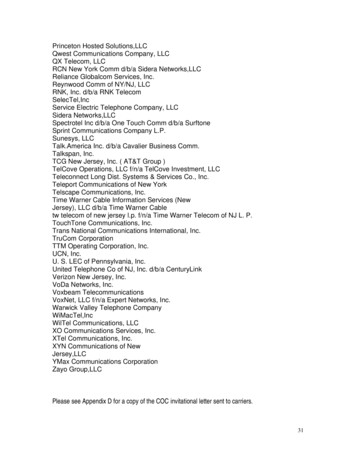

R E V I E W S & A N A LY S E STable 1. Handoff VIRONMENTALDISTRACTIONSINSUFFICIENTTRAINING ANDEDUCATIONMissing or incompleteinformation1,2No formal processin place1Lack of time, inabilityto follow up or shareadditional information2-5Lack of resourcesto implementhandoff program1,3Lack of leadershipsupport; organizationadministrative structurethat impedes opencommunication1,2Use of unclearlanguage, such asabbreviations andacronyms or similarsounding medicationnames2,5,6Lack of standardizedforms, tools, orprocess1-4,7Excessive noise or activity,including backgroundnoise, leading tosensory and informationoverload1-3,7Inadequate or nohandoff trainingprogram1,3,7Different levels of staffexperience and expertiseor staff with differentexpertise and training(e.g., MD and RN)2,4,5Differences incommunicationpatterns or language;cultural differences1-3,5Multiple handofftools used1Frequent transfers (e.g.,new admissions arisingduring handoffs) or highcensus1-4Staffing challenges (e.g.,too few nurses, high staffturnover)1-3,7Unclear roles andresponsibilities of teammembers1Process too timeconsuming orreports too long1,2Complex patients withhigh-acuity or new acutecare situation requiringimmediate care1-4,7Missing or unclear handoffpolicies and procedure1Lack of attention orresponsiveness ofreceiver3Illegible writtennotes from outgoingstaff2Interruptions, distractions,or multitasking during ahandoff report1,2,4,7Lack of teamwork andmutual respect; culture ofblame3Lack of mutual respector support1,3Difficulty accessingrecords2Cognitive bias4Unorganized or lengthyreports1Lack of privacy1,2,4,5Outgoing nurse notavailable1Staff fatigue or stress1,2,4Incorrect, extraneous,or irrelevantinformation1Poor lighting1LEADERSHIP/STAFFINGCHALLENGESElectronic device failure2Notes1. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Cunningham JM. Nursing handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Nurs. 2010 Apr;110(4):24-34; quiz 35-6. Alsoavailable: 09. PMID: 20335686.2. Friesen MA, White SV, Byers JF. Chapter 34: Handoffs: implications for nurses. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient safety and quality: an evidence-basedhandbook for nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2008. Also available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2649/.3. Halm MA. Nursing handoffs: ensuring safe passage for patients. Am J Crit Care. 2013 Mar;22(2):158-62. Also available: http://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2013454. PMID: 23455866.4. Bright J, Long B. ED handoffs - the problem and what we can do to improve. [internet]. emDocs; 2015 Nov 18 [accessed 2016 Sep 21]. [8 p]. oblem-and-what-we-can-do-to-improve/.5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss PB. Handoffs in hospitals: a review of the literature on information exchange while transferring patient responsibility or control. AnnArbor (MI): School of Information, University of Michigan; 2009 Jan 16. Also available: 8.6. Gardner LA. Health literacy and patient safety events. Pa Patient Saf Advis. 2016 Jun 16;13(2):58-65. Also available: oryLibrary/2016/jun;13(2)/Pages/58.aspx.7. VandenBerg AK. Patient hand offs: facilitating safe and effective transitions of care. Grand Rapids (MI): Kirkhoff College of Nursing, Grand Valley StateUniversity; 2013. 66 p. (Master’s Projects; Paper 1). Also available: rticle 1000&context kconprojects.Page 18Pennsylvania Patient Safety AdvisoryVol. 14, No. 1—March 2017 2017 Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority

(continued from page 17)shift, in shift, inshift, hand off, handoff,sign out, signout, cover, and to cover.The initial query resulted in 3,566 eventreports. Analysts reviewed the event reportsand excluded 2,001 with no mention of ahandoff or only a cursory mention (e.g.,a statement of intent to provide patientinformation at a future handoff). Analyststhen applied the following criteria whenreviewing and identifying handoff eventreports: the setting in which the handoffoccurred or should have occurred (e.g., shiftreports or unit transfers); discrepancies suchas omitted or inconsistent information; lackof physical checks of equipment, orders, ormedications; healthcare clinicians involvedin the handoff; and statements of no handoff performed.RESULTSOf the 1,565 handoff-related eventreports, 99.1% (n 1,551) were reportedas Incidents (e.g., near-miss events orevents that reached the patient but didnot cause harm). The remaining 0.9%(n 14) were reported as Serious Events(i.e., an event that reached the patientthat contributed to or resulted in harm).Handoff Settings and StaffInvolvementThree handoff settings were identified inthe event descriptions:——————Shift-to-shift transitions (39%,n 610 of 1,565)Unit-to-unit transfers (30.3%,n 474)Temporary coverage (e.g., during alunch break; 1.8%, n 28)In the final 28.9% (n 453), the handoffsetting was unidentified.Specific healthcare professionals were identified in the majority of the event reports(68.6%, n 1,074 of 1,565). In manycases, more than one class of healthcareprofessional was identified in the eventdescription, but their role as the giver orVol. 14, No. 1—March 2017 2017 Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authorityreceiver in the handoff was not consistently stated. They are grouped as follows:——————————[sure that the] patient’s RN wasaware [of the lab value]. Staff statedthat the patient had left the unit andwas possibly having a procedure. Thecharge RN called the [procedure room],reached the RN caring for the patient,and passed on these critical lab results.Registered nurse (86.4%, n 928 of1,074)Medical doctor (18.2%, n 195)Allied health professional (6.2%,n 67)Nonclinical staff (2%, n 22)Student nurse or resident (2%,n 21)During change of shift report, theoutgoing RN reported that new skinbreakdown on the patient’s buttockwas present. The outgoing RN statedthe wound was not there when hecared for the patient previously. Theoncoming RN’s assessment of thewound noted several areas of openskin. The patient was incontinentand requires frequent care. Barriercreams were applied to the skin. Thecertified registered nurse practitionerwas informed of [the patient’s] skinintegrity and the certified woundostomy and continence nurse sawpatient the next day.Completed HandoffsThe majority of the event reports identified the occurrence of a handoff, 81%(n 1,268 of 1,565), versus eventsreporting lack of a handoff (see Figure).Discrepancies between the informationshared and the patient’s condition wasthe most common problem. Event reportsthat identified a discrepancy withoutstating whether the staff addressed the discrepancy accounted for 59.2% (n 751 of1,268) of these reports; in the remaining40.8% (n 517) of the handoff reports,staff identified and followed up on handoff discrepancies. Discrepancies withoutan identified follow-up were found mostoften after a handoff occurred, 56.3%(n 423 of 751), and included omittedinformation in 61.5% (n 260 of 423)and a lack of a physical check or failureto clarify intravenous (IV) lines, orders,or skin conditions during a handoff in10.2% (n 43 of 423) of events.Good Follow ThroughThe following narratives illustrate efforts tosee patient issues through to completion:*Charge registered nurse (RN) receivedcall from the lab with a critical labvalue. Patient was not on the unitand no hand-off report was yet givenon the patient. The patient was [still]showing to be [on another unit]. TheRN [who received the critical labvalue] called the other unit to makeDiscrepancies Noted During Handoffwithout Indication of Staff Follow Through(n 136 of 751)Medication errors comprised more thanhalf of the 136 events in which discrepancies were noted during the handoff(55.1%, n 75) and included dose omission, extra or wrong dose, prescriptiondelays, monitoring errors, and incorrectmedication lists. The PA-PSRS miscellaneous or “Other” category comprised17.6% (n 24) of event reports; catheterline problems (e.g., infusion rates,infiltrates) and patient identificationissues accounted for the majority of theseevent reports. Errors in procedures, tests,or treatments included problems such asdelays in providing treatments or receivingtest results, missed treatments, or dietaryissues and accounted for 14.0% (n 19)of these event reports. The remainingevent reports involved transfusions, skinintegrity, equipment problems, and complications of procedures, tests, or treatments.* The details of the PA-PSRS event narrativesin this article have been modified to preserveconfidentiality.Pennsylvania Patient Safety AdvisoryWhile giving handoff report in theOR, the [outgoing] nurse noted anPage 19

R E V I E W S & A N A L

inspection of the patient to confirm the accuracy of information conveyed.1 Handoff communications coordinate patient care by passing essential information about a patient’s health status and responsibility for the patient’s care from one healthcare worker to another. They occur at change of shift (e.g., attending physicians, nursingFile Size: 449KBPage Count: 11