Transcription

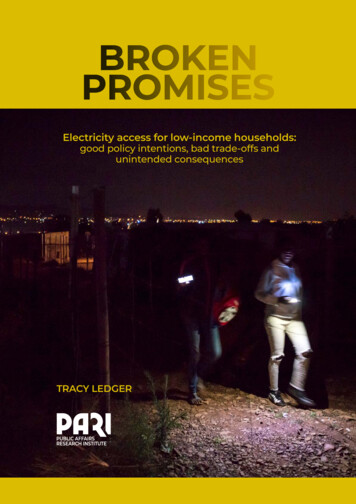

BROKEN PROMISESINTRODUCTIONBROKENPROMISESElectricity access for low-income households:good policy intentions, bad trade-offs andunintended consequencesTRACY LEDGER1ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

ENERGY AND SOCIETYWORKING PAPER #2APRIL 2021THIS REPORT WAS MADE POSSIBLE BYFUNDING FROM AGORA ENERGIEWENDEPHOTOGRAPHS BYBRAM LAMMERS PHTOGRAPHYNOTE:In this paper we have used the term energy to indicatewhat is more accurately a particular sub-category ofenergy — electricity and its common substitutes. In turn,when we refer in this paper to the conceptualisation of ajust transition in South Africa, we are making particularreference to that part of the transition narrative thatdeals with alternative (renewable) electricity productionmodels, rather than all energy issues.

TABLE OF CONTENTS1.INTRODUCTION .11.1. Background . 11.2. Modelling energy distribution and poverty . 31.3. Affordable access: policy promises versus implementation reality. 41.4. Structure of this working paper . 72.THE POLICY CONTEXT:WHAT HAPPENED TO THE GOAL OF AFFORDABLE ACCESS? 92.1. The policy promise of affordable energy for all. 92.2. The gap between White Paper promisesand policy reality. 123.THE TRADE-OFF BETWEEN LOCAL GOVERNMENT’SFINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY AND AFFORDABLEACCESS TO ENERGY.213.1. The role of local government in energy acccess. 213.2. The FBE trade-off no one knows about . 263.3. The failure of oversight and governance . 344.SUMMARY AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS.384.1. Summary of findings. 394.2. Policy recommendations. 40REFERENCES.42

They always promise us free electricity, theycannot turn against us and say we must pay.Pay for what, what happened to the -free-electricity-promise-north-residents/ (20 February 2019)

BROKEN PROMISESINTRODUCTION1. INTRODUCTIONPoverty has received scant attention from an energyperspective. This is remarkable given that energy is centralto the satisfaction of basic nutrition and health needs, andthat energy services constitute a sizeable share of totalhousehold expenditure in developing countries.21.1. BackgroundThe ability of all South African households to access sufficient quantities ofaffordable, clean (i.e. non-polluting) and safe energy is directly related to both animprovement in households’ standard of living, and the country’s ability to achieveits decarbonisation targets, through (at least) the following factors: Affordable access to clean energy facilitates the preparation and storage(refrigeration) of food and the ability to work, read and study after dark. Affordable access supports multiple livelihood opportunities, from smallscale home-based manufacturing to the ability to keep a cellphone charged(and thus to stay in contact with potential job opportunities). Affordable access reduces the share of energy expenditure in householdexpenditure, effectively making more resources available for otherbasic necessities, notably food and transport. Given that 80 per cent ofSouth African households cannot afford to purchase a basic basket ofnutritious food3, even small amounts of extra money for food purchasescan significantly affect a household’s nutrition status. The ability to pay fortransport, in turn, is key to accessing employment opportunities. Safe energy greatly reduces the risk of house fires and associated loss of lifeand property. Clean energy reduces the negative health impacts associated with high levelsof indoor air pollution caused by energy sources such as coal, animal dungand firewood. Clean, safe and affordable energy sources tend to benefit womendisproportionately, since they often have the primary responsibility forpreparing food and in the absence of such energy sources must often walklong distances to source items such firewood.2United Nations Development Programme, Energy After Rio: Prospects and Challenges, New York: United NationsPublications, 1997, p8.3Ledger, 2016.1ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESCHAPTER ONEPARI’s initial modelling of the linkages between energy and household poverty4indicates that whether or not households actually have access to sufficient cleanand safe energy that they can afford is determined in large part by the structureand operating model of the energy distribution system. Energy generation modelsimpact the national level of carbon emissions, as well as the baseline cost of energy.But it is the distribution model in South Africa that has the most significant impacton whether or not households can actually access clean and safe energy withinhousehold income constraints. When they are unable to do so, they either turnto dirty (i.e. polluting) and/or unsafe sources or make do without. Both of thesedecisions negatively affect a household’s standard of living and quality of life. Sinceit is the poorest households that are disproportionately affected, the result is toworsen inequality.We believe that a truly just energy transition must incorporate the basic principlesof energy justice, which we would define as all households having access tosufficient affordable clean and safe energy. In turn, the details of the dominantdistribution model are central to whether or not we can achieve energy justice.Despite the importance of energy distribution in creating (or undermining) SouthAfrica’s socioeconomic development and transformation goals (inclusivity, equalityand poverty reduction), the issue has to date received very little attention in thelocal just transition narratives. In these narratives, the definition of the social welfareaspects of transition have largely been limited to those of employment (or futureunemployment) in the coal sector, and the negative impact of the move away fromcoal on areas where it is the main economic activity.Policy making (particularly in the macro-economic resource-constrainedenvironment in which we currently find ourselves) is fundamentally about choosingwhich trade-offs to make, among multiple and competing goals. Those choices, inturn, cannot be made optimally without a full picture of what those trade-offs are,and the likely implications of different choices. The problem, as we currently viewit, is that because of the effective ‘invisibility’ of energy distribution as a problemto be addressed in any meaningful just transition, it is unlikely to receive the policyattention it requires. As a result, decisions that effectively result in exacerbatingpoverty are being made without full cognition of the trade-offs being made. Ouraim is to remedy that a-just-energy-transition/2ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESINTRODUCTION1.2. Modelling energy distribution and povertyPARI’s Energy and Society Programme was established in 2020 to address theseperceived shortcomings in the dominant definitions of what constitutes a justtransition. The aim of the programme is to investigate in detail the wide range ofsocial justice issues that originate in the distribution part of the energy system, thatare not currently on the just transition agenda. Our preliminary research indicatesthat the current structure and governance of the energy system actively underminethe poverty and inequality reduction goals of South Africa’s National DevelopmentPlan (NDP). Via a number of different but interconnected pathways, the currentdistribution system is actively and significantly contributing to increased povertyand inequality in a manner contrary to the intentions of both South Africa’s propoor transformation agenda and original policy intentions, with respect to thedevelopmental role of energy in a post-apartheid society.Our central premise is that there can be no just transition without a just distribution.That is, we need to incorporate a much more rigorous understanding of the multipleways in which the current structure and operation of the energy distribution systemundermine our goal of energy justice.The first working paper in this series contains an overview of the structure andoperation of the energy distribution sector in South Africa, and proposes a modelillustrating the causal linkages between the current form of that distribution sectorand household poverty and inequality. In this model, the central factor contributingto poverty and increased inequality was determined to be affordable access tosufficient clean and safe energy. Access of this kind is positively associated with areduction in poverty and inequality. Conversely, if households are unable to accesssuch energy at a cost that they can afford, there are multiple negative implications: Energy costs as a percentage of household expenditure will increase,reducing the amount of money needed for other basic necessities, such asfood and transport. Households look for other sources of energy, many of which come withserious negative side-effects, including indoor pollution and an increased riskof house fires. If enough households are forced into using dirty (polluting) energy sourcesbecause of the relative cost of clean energy, the effective result can be todilute national decarbonisation efforts. Unaffordable electricity drives many households toward illegal connections,which have both safety and system integrity consequences.The model draws our attention to a series of causal drivers — factors in the energydistribution system that are the most important for determining the nature andscale of the impact on poverty and inequality. These drivers determine the costof energy and the nature and terms of access to energy. The more these driversincrease the cost of clean and safe energy — and thereby undermine access — thegreater the negative impact on poverty and inequality.3ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESCHAPTER ONEThe most important drivers identified in our analysis included: Energy policy and energy system governance, which includes institutionalarrangements. This governance structure determines what actually getprioritised in the energy distribution system (and which isn’t always identicalto original policy intentions), and thus determines which trade-offs are made. Local government, given its central role in determining both the cost of, andaccess to, clean and safe energy. Both the local government fiscal framework(which depends on municipalities in aggregate earning significant surpluseson electricity sales) and the ability of local municipalities to determine whogets access to subsidised services and who does not are the key factors in thisrespect.1.3. Affordable access: policy promises versusimplementation realityAn overview of the current South African household energy access landscape paintsa grim picture: Significant numbers of households clearly do not have access to the amountsof clean energy that they require, at a cost that they can afford. This isevidenced by widespread electricity disconnections in poor areas, due to thenon-payment of accounts, high rates of illegal electricity connections,5 andwidespread protests about unaffordable electricity access.6 Despite high household electrification levels (around 85 per cent)7 manyhouseholds are forced into using dirty (polluting) and unsafe energy sourcesbecause they cannot afford to pay for the amount of electricity they require.A conservative estimate is that there are ten shack fires a day across SouthAfrica (Wang et al 2020): this implies that thousands of homes have beendestroyed by fire over the past five years, representing an almost total lossof all possessions for the affected families (who are overwhelmingly poorfamilies). Hundreds of people may have died in these fires, with many moresuffering serious injury. Indoor air pollution in many South African homes issignificantly higher than in most industrial areas (where outdoor air pollutionis more visible) and is estimated to cause around 1,400 deaths of childreneach neral Household Survey, indoor-airpollution-study/#: :text %20a%20few%20industrial%20hotspots.4ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESINTRODUCTIONGiven this situation, it may come as a surprise to learn that South Africa has a clearpolicy regarding universal access to sufficient safe and affordable energy for all poorhousehold (and small businesses and small farmers), set out in the 1998 White Paperon Energy. The questions we have to ask are — what went wrong, and how can weget back on track to realising the White Paper’s objectives? Proposed answers tothe second question should, we believe, be incorporated into existing just transitionstrategies.This working paper focuses on how the affordable energy access goals of SouthAfrica’s energy policy have been undermined: our analysis indicates that this isthe result of a combination of poor system governance, the failure to allocate clearaccountability for delivering affordable access, haphazard institutional alignmentand an overarching failure to identify and address critical competing policy tradeoffs, particularly between affordable energy access for households and municipalfinancial viability .5ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESCHAPTER ONEMany of these negative outcomes originate in the local government sphere ofthe state — in the structure of its revenue model, in the priorities emphasised bynational departments with key oversight roles over municipalities, and in the centralgatekeeper role that local municipalities play in determining who gets access tosubsidised services and who does not. Certainly, there are multiple weaknesses inthe overarching policies that local government is responsible for implementing(which weaknesses need to be addressed), but the manner in which these havebeen implemented by local government has made a bad situation even worse.The current operation of the energy distribution system is actively and significantlycontributing to increased poverty and inequality, as is detailed in this workingpaper. Key oversight institutions are effectively reproducing and entrenching theseoutcomes, either by neglecting their mandated oversight roles in respect of energyaccess, or by emphasising competing outcomes inherently at odds with a pro-poorenergy agenda.This situation is completely contrary to the intentions of both South Africa’s pro-poortransformation agenda (including the central role of local government in deliveringthat agenda) and original policy intentions concerning the developmental roleof energy in a post-apartheid society. These outcomes also have the potential toundermine the decarbonisation goals being pursued in the transition from coal toclean energy. Effectively, by ignoring the details of what is actually going on in ourenergy distribution system, we are building and entrenching two parallel energysystems: a visible, clean system based on renewable energy generation to whichaccess is effectively limited, alongside a largely invisible, dirty and dangerous systemthat is the only option for millions of households.Most of these negative outcomes reflect a failure of national policy coordination,coherence and alignment, and the siloed nature of the state (where nationaldepartments focus only on their own narrow mandate and largely ignore crosscutting developmental objectives), rather than any specific malicious intent on thepart of the state. However, this is meagre comfort to the millions of South Africanswho have effectively been denied the access to affordable and safe energy promisedto them more than twenty years ago.This working paper focuses on three key interlinked issues: The failure of policy and plans to give effect to the comprehensive affordableaccess goals of the 1998 White Paper on Energy, even where it was clearlyanticipated that they would do so; The nature and outcomes of a conflict of interest (between the financialviability of municipalities and the ability of low-income households to accessaffordable, clean and safe energy) inadvertently produced by the currentoperation of the local government fiscal framework; and6ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESINTRODUCTION The multiple gaps in the overarching governance system which have bothprevented any ‘big-picture’ assessment of the reality of affordable access toclean and safe energy, and not made any one organisation responsible forachieving this goal.These factors have underpinned and mutually reinforced each other in a long-term(and escalating) vicious cycle that contributes directly to deepening householdpoverty and exacerbating inequality (that is, the effects of this vicious cycledisproportionately impacts poorer households).Our continued failure to recognise these causal linkages and drivers carries thevery real risk of entrenching them into any new generation regime. This will makethem almost impossible to undo. We have a window of opportunity to rethink andrestructure our entire energy system, to make it fully aligned with reaching bothour decarbonisation goals and contributing significantly to poverty reduction andincreased equity. But these latter goals will not be fully achieved by reaching ourdecarbonisation goals alone. Nor will they be fully achieved under current limiteddefinitions of what constitutes a just transition.There is a case to be made that the goal of affordable and secure energy accesswill be facilitated by decarbonisation, and that decarbonisation will be facilitated bybeing designed and implemented as part of a wider green-and-fair developmentstrategy.1.4. Structure of this working paperChapter 2 of this paper outlines the policy trail, beginning with the 1998 White Paperon Energy, through the policies and regulation designed (in theory) to give effect toits intentions, tracking how the original policy intentions have either been dilutedor erased over the past 22 years. Close attention has been paid to the free basicelectricity (FBE) policy in this analysis.Chapter 3 analyses one of the most important factors that is negatively impactingaffordable access to energy and resulting in one of the invisible policy trade-offsreferred to above — the local government fiscal framework. Not only does thestructure and operation of this framework actively undermine the goal of affordableaccess, but the manner in which municipalities have implemented the FBE policyhas effectively deprived millions of households of that electricity allowance.Chapter 4 summarises our findings and makes some recommendations for howthe current situation could be improved.7ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESCHAPTER ONE8ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESTHE POLICY CONTEXT: WHAT HAPPENED TO THE GOAL OF AFFORDABLE ACCESS?2.THE POLICY CONTEXT:WHAT HAPPENED TO THE GOAL OFAFFORDABLE ACCESS?The main theme of this working paper is unintended consequences,largely generated by the challenge of achieving complex developmentalgoals in a fragmented institutional and governance environment. Theresult is effective trade-offs among competing policy goals, which tradeoffs are deeply prejudicial to poor households. However, they remain largelyinvisible.To investigate how these unintended consequences are generated — to present acomprehensive account of how we arrived at this position — we bring together arange of different threads. This chapter begins with an overview of the original policygoals of affordable energy access for a wide range of users, followed by a discussionof how those goals have been implemented — or not, which is the more commonoutcome. It is the failure of policies intended to give effect to the White Paper toactually do so which have contributed significantly to the situation in which we findourselves.2.1. The policy promise of affordable energy for allThe promise of affordable, clean and safe energy for all South Africans is a recurringthread across multiple policy documents and national plans. This goal was clearlyarticulated in the 1998 White Paper on Energy (RSA, 1998a), which listed the followingas the first of five long-term policy objectives for a transformed and developmentalenergy sector:Government will promote access to affordable energyservices for disadvantaged households, small businesses,small farms and community services. The achievementof this objective is fundamental to government’sreconstruction and development programme, and to thefuture socioeconomic development of our country (ouremphasis).It is important to note that the use of the word promote indicates an active role forthe state in achieving this goal, and not merely as an observing bystander.9ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESCHAPTER TWOThe following was offered by the White Paper as some of the reasons why affordableenergy access was considered so very important for reducing poverty and inequality,and for achieving socioeconomic development targets:The environmental effects of household energy use areparticularly severe on the rural poor, who use fuelwoodas their primary energy source. Coal-use in urban areasalso results in indoor air pollution with serious healthconsequences. With both fuels, pollution in many casesexceeds World Health Organisation standards.Energy security for low-income households can help reducepoverty, increase livelihoods and improve living standards.Government will determine a minimum standard for basichousehold energy services and monitor progress over time.People must have access to fuels that do not endangertheir health. Basic energy needs must consider costs,access and health.Productive activities in underdeveloped areas willeconomically empower the poor. Energy, particularlyelectricity, is a key requirement for these productiveactivitiesThe White Paper was also clear on what exactly this objective implied in terms of thetangible outcomes to be achieved:Energy should therefore be available to all citizens atan affordable cost. Energy production and distributionshould not only be sustainable but should also leadto improvement of the standard of living for all of thecountry’s citizens.The White Paper made it clear that ‘government is committed’ to promoting thisobjective. This is an important point to remember: the state made a clear and publiccommitment to what it considered to be the most important long-term objectiveof its energy policy.It is also notable that this objective — access to affordable energy services — was notjust going to be delivered to a limited number of the poorest households: instead,small enterprises and small farmers were also going to benefit — all citizens wouldhave access at an affordable cost. This wide definition of policy beneficiary was aclear recognition of the importance of affordable access to clean and safe energyin facilitating livelihood generation, a more equitable distribution of businessownership, and the success of the land reform programme.10ENERGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESTHE POLICY CONTEXT: WHAT HAPPENED TO THE GOAL OF AFFORDABLE ACCESS?This, in turn, echoed the general policy sense that close to full electrification of SouthAfrica was central to the ambitious post-1994 transformation agenda. The IntegratedNational Electrification Programme (INEP) was set up to connect all energy users tothe grid, save for a few areas where this was deemed to be prohibitively expensive,either because of the terrain or a very small number of users in remote areas (Bekkeret al, 2008). It should be noted, however, that INEP’s goal is to provide a physicalaccess point to as many users as possible. It is thus not in any way concerned withthe issue of the affordable access that was the number one objective set out in theWhite Paper, since it plays no role in determining the tariffs that users pay once theyare connected.The drafters of the Energy White Paper were clear that physical access was notthe same thing as affordable access, and therefore that additional measureswere required in order to ensure that this objective (affordable access) wasactually achieved: ‘many people cannot afford to use electricity optimally, even ifthey have access to it’ (p30).Unfortunately, the White Paper did not contain any guidelines or targets fordetermining affordability (such as a maximum percentage of household expenditureto be allocated to energy). It is worth remembering that electricity prices in 1998were significantly lower in real terms than they currently are. In just ten years, theelectricity price has increased by more than double the consumer price inflationrate.9 Thus, the question of affordability may not have appeared as urgent in 1998 asit does now, when tens of thousands of households face disconnection because oftheir inability to pay for electricity.The White Paper also contained a clear vision for significantly restructuring theelectricity distribution sector: it proposed that local municipalities would no longerhave a role in distribution (the authors were particularly critical of the principle ofusing electricity revenue to cross-subsidise other municipal activities). Instead, theWhite Paper envisaged a system where all distribution was consolidated under anumber of regional electricity distributors (REDs). We might assume that the planwas that these REDs would directly address the issue of affordable access, sinceit would presumably fall under their distribution mandate, but the structure wasnever implemented.The National Development Plan (NDP) was released in 2011 and is currently theoverarching apex socioeconomic development plan for South Africa. The NDPproposes that higher living standards — one of its key priorities — can be achievedthrough ‘a combination of increasing employment, higher incomes throughproductivity growth, a social wage and good-quality public services (NPC, 2011, p25).The social wage includes social grants, subsidised or free public services (such ashealth and education) and subsidised or free basic services (notably electricity,water and sanitation). The aim of the social wage package is to raise the livingstandards of those who are unemployed, or whose wages do not cover their basicliving requirements, by compensating them for their lack of RGY AND SOCIETY WORKING PAPER #2

BROKEN PROMISESCHAPTER TWOThe main themes that emerge from the Energy White Paper and the NDP arethose of universal access to a quality service (in the case of energy this is generallyintended to mean a formal electricity connection) and that the service be providedeither free or at a cost that is affordable for households. As the NDP pointed out —‘many households are too poor to pay the costs of services’, implying that effectiveaccess requires the state to subsidise the difference between what householdscan afford to pay and the cost of a basic requirement. It should be noted that theNDP also does not set any benchmarks for how the affordability in question is to bedetermined, or what exactly constitutes being too poor to pay for a service.10So what exactly has been done since 1998 to realise the primary objective of affordableaccess to energy for all citizens? The short answer is — very little.2.2. The gap between White Paper promisesand policy realityThe White Paper on Energy did not deal with the details of how its objectives inrespect of affordable access to energy were actually to be achieved — this is not thepurpose of such a document. However, it was intended to be the guiding documentfor all subsequent legislation and plans: it was this legislation and these plans thatwere meant to give full effect to the intentions of the White Paper (in the absence ofwhich it would be no more than a lengthy document).The first important policy document intended to deliver the objectives of the WhitePaper (of which affordable access to energy for households, small business andsmall farmers was the premier objective) is the National Energy Act of 2008 (RSA,2008). The word affordable appears only twice in that Act: right at the beginning,when the aim of the Act is described (‘to ensure that diverse energy resources areavailable in sustainable quantities

BROKEN PROMISES CHAPTER ONE PARI's initial modelling of the linkages between energy and household poverty4 indicates that whether or not households actually have access to sufficient clean and safe energy that they can afford is determined in large part by the structure and operating model of the energy distribution system. Energy generation .