Transcription

2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORTThe Impact of theCOVID-19 Pandemic onChildren’s Mental HealthWhat We Know So Far

The Child Mind Institute is dedicated to transforming the lives of children andfamilies struggling with mental health and learning disorders by giving themthe help they need to thrive. We’ve become the leading independent nonprofitin children’s mental health by providing gold-standard evidence-based care,delivering educational resources to millions of families each year, trainingeducators in underserved communities, and developing tomorrow’s breakthroughtreatments. Together, we truly can transform children’s lives.AUTHORSKelsey OsgoodHannah Sheldon-Dean, Child Mind InstituteHarry Kimball, Child Mind InstituteCONTRIBUTING PARTNERThe Morgan Stanley Alliance for Children’s Mental HealthThe Morgan Stanley Alliance for Children’s Mental Health combines the resourcesand reach of Morgan Stanley with the knowledge and experience of distinguishednonprofit partner organizations to help deliver positive, tangible impact on thecritical challenges of stress, anxiety and depression in children, adolescents andyoung people.CHILD MIND INSTITUTE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH COUNCILJudy Cameron, PhD, University of PittsburghKathleen Merikangas, PhD, National Institute of Mental HealthCHILD MIND INSTITUTE STAFF REVIEWERSMichael Milham, MD, PhD, Vice President of ResearchAki Nikolaidis, PhD, Research Scientist, Center for the Developing BrainDESIGNJohn Stislow, Stislow DesignAbby Brewster, Child Mind InstituteRECOMMENDED CITATIONOsgood, K., Sheldon-Dean, H., & Kimball, H. (2021). 2021 Children’s Mental HealthReport: What we know about the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on children’s mentalhealth –– and what we don’t know. Child Mind Institute.

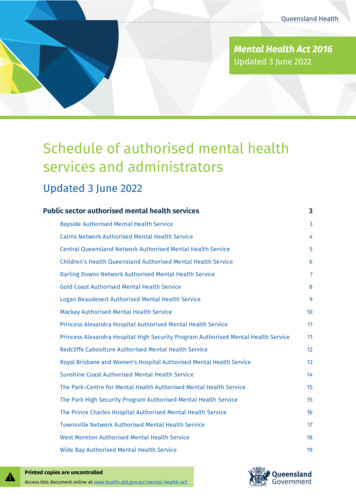

TABLE OF CONTENTSLET TER FROM OUR PRESIDENT3 Practicing Preventionand Building ResilienceINTRODUCTION4 The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic onChildren’s Mental Health: What We Know So FarONE5 What Do We Know About the COVID-19Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Health inChildren and Adolescents?TWO9 T he Child Mind Institute’s Research onYouth Mental Health and the CoronavirusTHREE13 Perspectives From Teens and EducatorsCONCLUSION24 Key Conclusions2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT1

2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT2

LET TER FROM OUR PRESIDENTPracticing Preventionand Building ResilienceEven before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, mental health professionals werestruggling to meet the needs of the one in five children and adolescents with a mental healthor learning disorder. Then the pandemic hit, bringing an upsurge in youth reporting mentalhealth challenges. In surveys now, about 30–40% of young people say they feel anxious,depressed and/or stressed. Parents tell the same story when asked about their kids.The pace of disruption in our world is increasing, notslowing down. How can we reduce the mental healthimpacts of the next global public health crisis — and theremainder of this one?The first step is to identify who is most affected. TheChild Mind Institute has been devoted to tracking theimpact of COVID-19 on youth and families since the firstdays of the pandemic. The research highlighted in the2021 Child Mind Institute Children’s Mental HealthReport demonstrates that the most negative impactsof the pandemic have been concentrated in uniquelyvulnerable populations. Who are they? Poor kids. BIPOCkids. LGBTQ kids. Kids with unstable home lives. Kidswith mental health disorders like anxiety, depression orADHD — especially those who don’t get treatment. Kidswith learning disabilities. Kids with autism.The next step is determining how to help them weatherthe coming storms. We cannot solve the factors thatcontribute to risk — poverty, stigma, racism — all atonce. Instead, we must focus on protecting at-risk youthand fostering their resilience. How?Prevention and preparation. Most young people, asyou will see in this report, respond to challenges anddisruption with resiliency. Supporting resilience in at-riskpopulations is an important (perhaps the most important)tool in the behavioral public health tool belt. My colleagues in this field often talk about going beyond theemphasis on “risk” factors in order to focus our effortson how to build “protective” factors.Where do we instill resilience? Our families. Ourschools. Our health care system. The Child Mind Instituteapproaches this challenge in many ways, including by:}Giving families tools to help their children with ourFamily Resource Center}Providing curricula and teacher trainingin our School and Community Programs}Offering direct clinical care, supportand professional development}Running community research studiesof at-risk youth and resilienceBut we can’t do this alone. I hope you will read this report,use these findings to advocate for change, and join theChild Mind Institute’s mission to transform children’s lives.Best regards,Harold S. Koplewicz, MDPresident and Founder, Child Mind Institute2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT3

INTRODUCTIONThe Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemicon Children’s Mental Health:What We Know So FarIn this report, we examine the growing body of research on the effects of the COVID-19pandemic on children’s mental health, including the results of a survey of thousandsof parents conducted by the Child Mind Institute. Though our understanding of theseimpacts is still evolving, it’s clear thus far that despite the challenges of the pandemic,children and young adults are remarkably resilient and able to cope with the ongoingstress and uncertainty in healthy ways.At the same time, certain identifiable groups of people and children are more at risk fornegative mental health outcomes, and certain pandemic-related stress factors are likely tobe more impactful than others. Responding to the mental health impacts of the pandemiceffectively requires both tailoring supports to these vulnerable groups and, simultaneously,recognizing and building on the strengths and resilience that young people already possess.In Chapter One, we review the available data on the pandemic’s impact on children in generaland on certain subgroups within the general population. We also put the coronavirus pandemicinto historical context by looking back at the mental health effects of previous disasters.In Chapter Two, we look at the major conclusions of the Child Mind Institute’s own researchinto the experiences of caregivers and their children.And in Chapter Three, we examine the results of two recent surveys in which educators andteenagers were asked about their perceptions of specific challenges related to weatheringthe pandemic and starting a new school year. We also look at what sort of resources they feltwould help them navigate these issues.2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT4

CHAPTER ONEWhat Do We Know About the COVID-19Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Healthin Children and Adolescents?Key TakeawaysThe pandemic has had meaningfulimpacts on mental health, but noteveryone has been affected to the samedegree or in the same way.Economic instability, living in an areahit harder by the virus, and preexistingmental health problems are some ofthe most notable risk factors for adultsexperiencing mental health challengesduring the pandemic.There is less information about children’smental health specifically, but theavailable data indicate that many of thesame risk factors apply.However, research and historical contextalso suggest that young people areresilient and that many (especially thosewith fewer risk factors) will likely emergefrom the pandemic without significantmental health challenges.2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORTThere is much more data on how the pandemic hasaffected the mental health of adults than there is on howit has impacted children and adolescents. While we’reconcerned here with the latter, looking at studies onadults is an important means of gaining insight into kids’experiences. One of the most salient takeaways from thestudies conducted is that while COVID-19 has broadlyaffected the mental health of many adults, not everyonewas affected to the same degree or in the same way.5

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, manyheadlines warned that a global mental health crisiswas coming.1,2But in reality, not everyone’s mental health was affectedequally (and, as we’ll see later, many people proved to beextraordinarily resilient).Studies showed that groups who lived in certain environments tended to be more afraid of the virus, and thisfear was itself associated with higher levels of anxietyand depression. These groups included:}Those who lived in areas where the outbreak wasmore severe}People who lived in urban areas3}Families of health care workersStudies also consistently showed that during thepandemic, certain subgroups reported higherlevels of stress and symptoms of mental healthdisorders like anxiety and depression regardlessof their environment. These groups included:}Women}Racial minorities, particularly Latinx people}People with preexisting mental health problems}Parents of young children4,5COVID-19 also didn’t occur in a vacuum: even beforethe virus, frustration over persistent economic disparityhad grown, particularly in the United States, whereincome inequality is higher than in almost any otherdeveloped nation.6 The pandemic led to mass job lossesand disproportionate professional stressors for peopleworking low-paid jobs with little professional security,such as nursing home aides and delivery workers.Those who experienced job loss or were otherwiseeconomically vulnerable during COVID-19 wereat high risk of developing anxiety or depression,which fits in with what we already knew about thestrong connection between low income and mentalhealth challenges.7, 8Increased stress had notable behavioral ramifications.Studies showed that women and parents of youngchildren reported drinking more alcohol, and thatparents who had experienced income loss were morelikely to lose their tempers and yell at their children.9, 10Studies have shown that children, like adults, havealso reported higher rates of distress during theCOVID-19 pandemic.11}In a survey conducted in late March 2020 by theUK charity YoungMinds, 83% of young people withpreexisting mental health needs reported that thepandemic had worsened their mental health to somedegree.12}According to a study published in October 2020,22.28% of children and adolescents in China exhibitedsigns of depression, compared to the 13.2% estimatedin previous research.13}Researchers studying the effect of lockdowns onparents and children in Italy found that children’semotional and behavioral challenges were significantlyaffected by how stressed their parents were, and howtheir parents responded to this stress.14Those who experienced job loss or were otherwiseeconomically vulnerable during COVID-19 wereat high risk of developing anxiety or depression,which fits in with what we already knew aboutthe strong connection between low income andmental health challenges.7,82021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT6

A growing body of research has shown that formany people, the distress experienced early onin the pandemic has evened out over time.27Though there are less data overall on how the pandemichas affected children’s mental health as opposed toadults’ mental health, the information we do havesuggests some overlap between the risk factors fordistress among children and adults. Like adults, childrenwho lived in urban areas and those whose familiesexperienced either economic uncertainty or a foodshortage showed greater levels of psychological distressthan others. They often exhibited signs of:}Anxiety}Depression}Attention issues}Sleep disturbances15, 16In times of crisis at home, many children find solace atschool, but during the pandemic, kids around the worldwere forced to switch to remote learning. While somesocially anxious kids experienced relief at this change,many more experienced it as a loss of vital outlets likesports and socializing with friends.17 The increasedreliance on the internet also raised red flags for someresearchers, who have linked increased screen time topoorer sleep habits, difficulty focusing and problematicbehavior.18 In addition, kids who used the internet to takepart in school lessons might have utilized their greateraccess to media to overconsume COVID-related news,which has been associated with higher levels of stress.19The evidence also suggests that for children withautism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their families,the disruption to schooling and to services like occupational, speech or applied behavioral therapies wasespecially significant. In a survey of 3,502 caregivers ofchildren with ASD:}64% reported that the lack of services had“severely or moderately” impacted their child’ssymptoms or behavior.}80% of those with preschool-aged children on theautism spectrum said the disruption caused thosechildren “extreme to moderate stress.”2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT}Though many therapeutic services were continuingvia telehealth, most survey respondents were nottaking advantage of them after a month, and thosethat were “reported minimal benefit.”20But while the risks to vulnerable young people are real,it’s hard to say what the long-term impacts for most kidswill be.COVID-19 was (and is) a unique global phenomenon formost people alive today. Historical precedents, whereavailable, show that experiencing a traumatic event maybe linked to worse mental health in subsequent years.But many of these events were singular catastrophes,like tsunamis or earthquakes, that affected a relativelysmall pool of people, whereas COVID has impactednearly everyone. Also, few of these previous studiesfocused on children.}In one study of the mental health effects of theChernobyl disaster, rates of depression, anxietyand PTSD were two to four times higher among“Chernobyl-exposed” subjects than the generalpopulation up to 11 years after the disaster.21}In looking at the experience of evacuees after theFukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011, researchersfound that 14.6% of their subjects expressed markedlevels of psychological distress, mostly related touncertainty over the long-term ramifications ofradiation exposure, compared to just 4.4% of thegeneral Japanese population.22}Children who witnessed the events of the 9/11 attackswere nearly three times more likely to have symptomsof depression or anxiety and nearly five times morelikely to have sleep problems, relative to those whohad not been exposed.237

The closest corollary to COVID in recent history is theSpanish flu of 1918, but little research was done on thelong-term mental health ramifications of that pandemic.Some research has indicated an uptick in psychiatrichospitalizations or suicides beginning at the onset ofthe Spanish flu, but it’s hard to assess its validity.24Studies of more recent epidemics and disasters haveconsistently found that the perception of impact ofthe event was one of the most potent influences onlonger-term outcomes. Accurate and consistentinformation that can allay these concerns is thereforea critical public health priority. Accordingly, conflictingmessages about the pandemic and mitigation steps arelikely at least partial explanations for the widespreadincrease in reported stress and anxiety in youth in theUnited States. 25 The Surgeon General of the UnitedStates has recently released a report that providessome measures to reduce the misinformation that maybe driving these negative mental health outcomes.26So, while history suggests that some long-term mentalhealth challenges may persist in the years following thispandemic, the evidence is far from conclusive.2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORTThere is also cause for optimism: a growing bodyof research has shown that, for many people, thedistress experienced early on in the pandemic hasevened out over time.27 Psychologists and otherprofessionals have invoked the idea of a “psychologicalimmune system” that protects us much the same waythe biological one does.28 Ultimately, we expect that, likeadults, most kids are naturally resilient, but others mayrequire extra support from their parents, social networks, health care providers, and others in their orbit.In the next chapter, we’ll look at some of the specificcharacteristics that put kids at greater risk for psychological distress during and after the pandemic. Thesecharacteristics include:}Having a preexisting mental health disorder,including but not limited to depression, anxiety,or ADHD}Having experienced a previous trauma}Being food insecure or economically vulnerable}Experiencing a disproportionate disruption toone’s daily schedule8

CHAPTER TWOThe Child Mind Institute’sResearch on Youth Mental Healthand the CoronavirusKey TakeawaysParent reports indicate that highpercentages of both adults and kidsexperienced psychological distressearly in the pandemic.Children in our study who lived infinancially unstable households orwho experienced food instabilityduring the pandemic experiencedworse mental health outcomes thantheir more financially secure peers.Our data indicate that a child’smental health three months beforethe pandemic began was the factormost closely correlated with theirmental health during the pandemic.2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORTFrom the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ChildMind Institute’s science team recognized a need forrobust research that could fill the gaps in the existingliterature and provide nuance to the dialogue. We knewthat the pandemic was making some children’s mentalhealth worse, but it was crucial to know which subgroupswere suffering most, and which aspects of the pandemicwere most impactful. In previous pandemics, like SARSand MERS, as well as catastrophes like earthquakes,most of the research was conducted long after the event.We wanted to track how people were coping in real time,and we are making a continuing effort to follow thechanging situation as we move into the new school year.9

With support from the Morgan Stanley Alliance forChildren’s Mental Health, the team at the Child MindInstitute joined forces with the National Institute ofMental Health and New York State’s Nathan KlineInstitute to create the CoRonavIruS Health and ImpactSurvey, or CRISIS.29 The survey delved deep into anumber of measures of well-being, including but notlimited to:}Mental health both before and during the pandemic}Lifestyle changes}Health behaviors including physical activity and sleep}Substance use}COVID-19 virus exposure and infection}Demographic information including race, profession,and physical healthIn April 2020, the survey was sent to 5,646 adultparticipants from the United Kingdom and the UnitedStates, mostly in areas that had been significantlyimpacted by COVID-19, like New York City, Manchester,London, and parts of California. About half of therespondents from each country answered on behalf ofthemselves, while the other half filled out the survey onbehalf of their children, who ranged in age from 5 to 17.Partner PerspectiveBefore the pandemic we launched the Morgan Stanley Alliance for Children’s MentalHealth in February 2020 with a 20 million commitment to address the increasingchallenges of stress, anxiety and depression in youth. We had no idea that withina month, the world would turn upside down and the very crisis we had identifiedwould explode. The pandemic is obviously awful, but there have been silver linings.The situation sped up the work of the Alliance and the collaboration across ournonprofit members, including the Child Mind Institute. Together, we have advancedgame-changing mental health care solutions for children and young people, especiallywithin vulnerable communities. And there has been a marked change in stigma, asparents, including our own employees, are openly discussing their children’s mentalhealth and actively seeking support and care. We have a long way to go, but I amheartened and hopeful that mental health can stay front of mind and that more willjoin Morgan Stanley and the Child Mind Institute in actively helping.”Joan Steinberg, president of the Morgan Stanley Foundation2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT10

Children who lived in financially unstable householdsor who experienced food instability during the pandemicexperienced worse mental health outcomes than theirmore financially secure peers.32We found some similarities — and some differences–– between adults’ and kids’ stressors.Our initial findings supported the idea that childrenand adults alike were experiencing higher levelsof emotional distress.About 70% of both children and adultsreported some degree of mental discomfort,resulting in loneliness, irritability or fidgetiness.ChildrenAdults55% of children felt more “sad, depressed orunhappy,” versus 25% of adults.30Adults generally said they were more “distracted,anxious, fatigued and worried” than their children.31One of the most telling findings from the initial wave ofthe study is that children’s moods during the pandemicwere most closely related to the lifestyle changes they’dexperienced, such as not being able to attend school,see friends, have in-person conversations with extendedfamily members, and being confined to their homesdue to lockdowns.33 These findings dovetail with otherresearch that has demonstrated the protective effectsof regular, predictable routines for children.34Though some studies have shown that strict lockdownsare a source of stress for adults, in our research, theadults generally ranked disruption to daily life as lessimpactful to their mental well-being than specific worriesabout COVID-19, such as fear of infection and illness.As was the case with many adult responders, our dataindicated that a child’s mental health three monthsbefore the pandemic began was the factor most closelycorrelated with their mental health during the pandemic.In other words, a child struggling with depressionprior to the pandemic was more likely to be strugglingduring the pandemic than one who was not.Like many other studies, this one was conducted during ashort window of time in locations that were experiencingvery high infection rates. In accordance with our desireto gain holistic, long-term insight into the pandemic’simpact on mental health, we’ve surveyed a portion ofour original subjects twice more since the first round ofresearch. We have begun publishing the data from thoselater rounds as well, and these early results indicatethat similar factors continued to be strong predictorsof mental health symptoms even many months intothe pandemic.35Children who lived in financially unstablehouseholds or who experienced food instabilityduring the pandemic experienced worse mentalhealth outcomes than their more financiallysecure peers.322021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT11

Practical Applications for Our FindingsOur research underscores the idea that for children atrisk due to preexisting mental health problems, everyeffort should be made to increase their access to care.This finding is especially relevant in the context ofprevious data that point toward ongoing deficienciesin children’s mental health care:}About half of the estimated 7.7 million children inthe United States who had a treatable mental healthdisorder in 2016 did not receive adequate treatment.36}There is a serious lack of accredited professionals,including child psychiatrists, therapists and socialworkers, in almost every state.37Our research also highlights the connection betweeneconomic hardship and mental health outcomes.As important as access to care is, promotingfinancial stability and food security for youngpeople and their families is an equally crucialmeans of supporting mental health.2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORTIn that vein, the Biden administration in the UnitedStates has recently rolled out a program to provide a taxcredit to American families, which is estimated to cutchild poverty rates by up to half and could be enormouslyimpactful on the mental health of America’s children.38Finally, the data indicate that minimizing disruptions todaily routines can do a lot to protect children’s mentalhealth, even in very stressful situations. Knowing thiscan not only help caregivers and educators set prioritiesat home and school — it can also guide public policytoward measures that minimize lifestyle disruptionsfor kids.In the next chapter, we’ll share personal perspectivesfrom educators, adolescents and children’s mentalhealth professionals. These anecdotal reports speakto many of the same needs that our own research andother studies have highlighted, and they offer insightsinto how these broad trends can shape individual lives.12

CHAPTER THREEPerspectives FromTeens and EducatorsKey TakeawaysEducators reported that their biggestconcerns about students’ adjustmentto the new school year were learningdeficits and anxiety over returning toschool in person.Educators also said they expectedeconomic hardship to be the highesthurdle for those students whoexperience it, more significant thaneither learning deficits or anxiety.Teenagers surveyed reported that theirbiggest worries about the new schoolyear were falling behind academicallyand experiencing social anxiety.Non-white teens reported more concernthan their white peers about nearly everyre-emergence issue, including negativeimpact of the pandemic on focus andacademic progress, coping with lossand grief, economic struggles or foodinsecurity, and mental health challenges.Nonetheless, teens were optimistic:67% agreed with the statement, “I amhopeful that I will adapt and reboundIn the last chapter, we discussed parents’ reports of howthe pandemic had affected their children’s mental health.Here, we complement the findings from parental perceptionsby summarizing reports from young people themselves.Because many school districts around the country areopen for full-time in-person learning this fall after a yearof remote or hybrid classes, we were especially interestedin whether or not teens felt prepared for this shift andwhat concerns they had over returning to the classroomenvironment. We also wondered what aspects ofre-emergence school employees were most concernedabout, and how those concerns could be best addressedby mental health professionals, school administrativebodies and the government.from the challenges of the pandemic.”2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT13

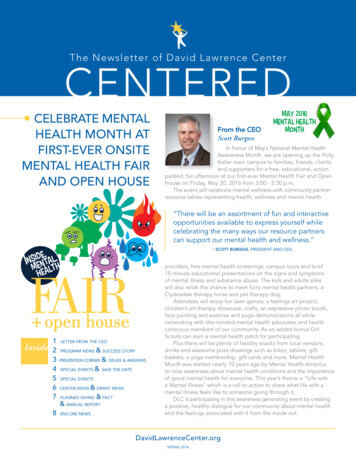

In the summer of 2021, the Morgan Stanley Alliance forChildren’s Mental Health conducted two surveys on thefollowing groups:}552 U.S.-based high school employees, includingteachers, administrators, school counselorsand nurses}516 U.S. teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19The surveys covered a wide variety of issues facingboth educators and students returning to in-personlearning, including:}Concern over handling pandemic-relatedacademic loss}Social anxiety}Coping with grief over the loss of a loved one,or helping students dealing with grief}Addressing economic hardship in the student body}Addressing trauma due to race, LGBTQ identity,disability, or other minority status in the student bodyTo learn more about the report on teenagers, mergence-program-teen-survey-factsheet.pdfAnd for more about the findings from educators, mergence-program-educator-survey-factsheet.pdfWhat Teachers ReportedNot surprisingly, a majority of educators we surveyedsaid they conducted remote learning at some pointduring the 2020–2021 school year. This figure changedsomewhat over the course of the year: 4 in 10 educatorssaid their school was fully remote in the fall, but that haddropped to 16% by spring.While a small portion of both students and educatorspreferred online learning to full-time in-person classes,many reported problems. Issues that students andeducators pointed to included increased studentdistractibility and the ease with which students couldneglect assignments or skip school altogether. Ninein ten educators reported that absenteeism was aproblem during the past year, with hybrid or onlinesettings being more affected.This high rate of absenteeism may have led to educators’reported concerns about loss of learning, academic focusand skill acquisition over the past year. Of the 12 potentialstudent re-emergence issues identified in the survey,educators rated “significant deficits in learning andacademic preparation” as likely to have the mostimpact on student learning this upcoming year.To what extent was student absenteeisma problem for your school/district duringthe 2020–2021 school year?40%11%49% Not a problem at all Minor problem Major problem2021 CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH REPORT14

“It is my job as a highNearly half of educators expect that students with significantdeficits in learning will have a large impact on the quality oflearning in the upcoming yearStudents with significant deficits inlearning and/or academic preparationschool teacher to coverbig areas of historycontent and to buildupon previous years’47%31%22%37%22%learning. There is notime in the curriculumStudents and families experiencingeconomic hardship42%Student anxiety about adjustmentto in-person learning41%34%25%to reteach things thatweren’t learned throughvirtual learning.”High school teacher A lot/a tremendous amount of impact Some impact No impact“After spending most ofthe year remote learning,Which one of the following issues do you expect to be thegreatest challenge for you during the upcoming school year?(2021–2022)Students with significant deficits inlearning and/or academic preparation15%Student anxiety about adjustment toin-person learning15%Student acting-out behaviormany [students] have lostappropriate social andcommunication skills.”School counselor11%Research indicates that students of color and/orthose with fewer economic resources are likely tohave experienced greater learning deficits.39 Theteache

Child Mind Institute has been devoted to tracking the impact of COVID-19 on youth and families since the first days of the pandemic. The research highlighted in the 2021 Child Mind Institute Children's Mental Health Report demonstrates that the most negative impacts of the pandemic have been concentrated in uniquely vulnerable populations.