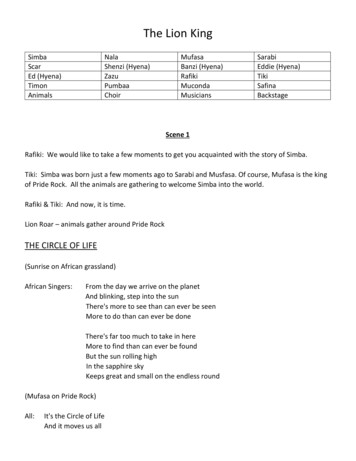

Transcription

KING’SJanuary 2008a newsletter for members of King’s College, CambridgePA R A D E

Editor’s LetterCollegenewsWhen I met former King’s ChaplainPatrick Magee at the Foundation Lunchlast March and learned that he was livingin retirement with a Muslim family inMorocco, I asked him for his reflections.These, together with the fact that Directorof Music, Stephen Cleobury, took the Choir to the Istanbul MusicFestival in June have provided an excuse to show you some King’sIslamic artefacts as well as to juxtapose one iconic building withanother. (King’s Chapel, completed in 1547, took over a hundredyears to build; the Blue Mosque, completed in 1616, took less thanten )Last spring the Development Office sent 3000 Non-ResidentMembers a survey asking what you thought about King’s andyour experience as students here. The College wanted to knowabout your preferences and interests and to hear your viewsabout communications and events at King’s. Six hundred and fiftyNRMs from matriculation years 1944 to 2003 returned the survey.Each question was divided into two parts. The first part askedyou for a ranking and the second for your comments. You hadquite a lot to say and your answers have given us many ideasabout how we might do some things differently.One finding was that, in spite of the College running severalwell-publicised events for Non-Resident Members each year,many of you still did not know about them. Many of you alsosaid that you felt you had to wait too long to see friends fromyour year group at reunions, or that you would like to come toan event that welcomed families.There’s no soft centre to this issue. The profile features ProfessorMegan Vaughan (KC 2003), an African history expert who works onslavery and famine; and Leila Blacking (KC 1995) writes about herhands-on work for the Red Cross at the end of the long Liberiancivil war. More than eighty King’s members currently live in Africa– King’s Parade welcomes your news and feedback.In response to your requests, the events programme has beenredesigned to welcome NRMs back to College once every fiveyears, and we will also be running an annual family-friendlyevent starting in 2008. A special black tie event has been addedfor years reaching the 50th, 55th and 60th anniversary of theirmatriculation.This issue also announces some anniversaries – the King’sSingers’ 40th (they are giving a concert in King’s in May), andKing’s Voices, the College’s mixed voice choir, have reached their10th anniversary. The Boat Club’s 150th anniversary is providingan opportunity for members to come for a dinner in June, and tofit in some nostalgic rowing too. Please also send in your rowingrecollections for a new book on the club – addressed to thesecretary of KCBC, Matthew Tancock.Another surprise was that so few of you knew that you allautomatically become members of the King’s College Associationupon graduation. The Association runs the annual KCA Dayin King’s and sponsors the publication of the King’s Register,the Who’s Who of Kingsmen – the last one was published in1998 and records details of Members up to and including thosematriculating in 1990. In addition to asking for a new register tobe published, you overwhelmingly favoured a password-protectedonline address book to keep in touch with friends. The KCA istaking on both of these projects in the coming year and will becontacting you to ensure that information about you is accurateboth in the Register and online.Your responses to the recent email survey have resulted in areinvigorated programme of events as well as more forwardplanning. See the back page for full details, and reunion informationfor 2009 and 2010.This is my last issue of King's Parade. Thank you for all yourcontributions, letters, suggestions, enthusiasm and support as thispublication has grown and developed over the last ten years.In the survey you were also asked how you would like to becontacted by the College. Some of you prefer to be contactedby post and others by email and even that depends on thesubject of the communication. Increasingly, your individualpreferences will be taken into consideration.With my good wishes for the future,Alison CarterYour comments provided marvellous, often inspiring insightsinto what you think the College does well and helpfulsuggestions about what it could do better. Thank you for takingthe time to let the College know what you think. Full results ofthe survey can be found online at: www.kings.cam.ac.uk/developmentPHOTO: ELIZABETH ENNION editor's letterkings.parade@kings.cam.ac.uk2What you had to say.To find out more aboutevents at King’s seewww.kings.cam.ac.uk/developmentor contact Amy Ingle inthe Development Office.events@kings.cam.ac.uk01223 331443Iznik ware, 16th Century, TurkeyEveryone who filled out the survey was entered into a draw foreither a case of College wine or dinner in the Saltmarsh Roomand a night in the Rylands Suite. Congratulations to DebbieEnever (KC 1999) who won a case of College wine and toMr Paul Lambert (KC 1988) who won the dinner and night inCollege.Joelle du Lac, Director of DevelopmentMany thanks to Mark Perkins (KC 1975) whose software wasused to interpret the survey data.

Peter Lipton (KC 1994), Fellow, died suddenlyin Cambridge on 25 November. He will be greatlymissed. His many contributions to the College,both intellectual and social, earned him therespect and affection of all who worked with him.Double accolade for Jealousy ofTradeIstvan Hont (KC1978) has beenawarded both theJ. David GreenstoneAward 2007 for thebest book in historyand politics, and theJoseph J. SpenglerBest Book Award 2007for the best book in thehistory of economics.“Jealousy of trade” refers to a particularconjunction between politics and the economythat emerged when success in international tradebecame a matter of the military and politicalsurvival of nations. Today, it would be called“economic nationalism”. Istvan Hont connectsthe commercial politics of nationalism andglobalization in the eighteenth century to theoriesof commercial society and Enlightenment ideasof the economic limits of politics.“This is a stunningly ambitious and eruditeproject that covers an extraordinary array offigures from Hobbes, Grotius and Pufendorf, tothe Physiocrats, Montesquieu, Hume, and Smith;just as important, it contributes distinctivelyto issues that occupy contemporary politicalscientists and political theorists, includingnationalism, socialism, republicanism,capitalism and globalization theory.” (From theJ. David Greenstone Award citation.)“ Jealousy of Trade provides an account ofthe development of modern political argumentfreed from the ideological distortions bredby party-polemical zeal. Its ambition here isconspicuous, but so too is its intellectual energyand imagination. It is a landmark contribution toits field.” Richard Bourke (QMUL) Times LiterarySupplement, 20 January, 2006.Istvan Hont is University Lecturer in the Historyof Political Thought. He was Senior ResearchFellow in charge (with Michael Ignatieff, KC1978) of the Research Centre’s project ‘PoliticalEconomy and Society 1750-1850’.Jealousy of Trade: International Competition andthe Nation-State in Historical Perspective. BelknapPress of the Harvard University Press, 2005.New Joint Centre for History andEconomicsKing’s College and the Harvard UniversityFaculty of Arts and Sciences have established aJoint Centre for History and Economics. The newJoint Centre will build on the current researchproject “Exchanges of Economic and PoliticalIdeas since 1760”, which is supported by theAndrew W. Mellon Foundation. The new Centrewill be administered from both sides of theAtlantic. Emma Rothschild (KC 1988) andGareth Stedman Jones (KC 1975) will be codirectors of the Centre in Cambridge, and EmmaRothschild will be the initial director of theCenter in Harvard.www-histecon.kings.cam.ac.ukNew Vice-ProvostDr Tess Adkins (KC 1972), retired at the endof 2007. Dr Basim Musallam (KC 1985) is thenew Vice-Provost.The Fourth of JulyEvery year on 4July Americanscelebrate. Mostbelieve themselvesto be celebrating thefounding of theircountry, which bycustom is said tohave occurred themoment a document,the Declaration ofIndependence, was signed in the State Housein Philadelphia on Thursday, July 4, 1776. TheDeclaration of Independence was in fact madeon 2nd July. On the 4th it was only signed by oneperson rather than through the collective act of56 individuals. Jefferson was not the sole authorof the document. Nor was it intended to markthe origin of a new nation. But after 50 years theday had begun to assume totemic significance.Peter de Bolla (KC 1976) teases out thetrue history of the Fourth of July, tracking themoments and symbols – the flag, the LibertyBell and Uncle Sam – which have helpedcreate the myths and practices of observancethat continue to make the 4th such a punctualmoment in the calendar of America.Peter de Bolla is Reader in Cultural History. Hewas a founder Editor of Granta and occasionallywrites about food and wine.The Fourth of July and the Founding of America.Profile Books. 15.99.The Book of InterruptionsWe are living in the Age of Interruption; moderntechnology is changing our forms of attention,everyday life is subject to more disruption thanever before. Edited by David Hillman (KC 2004,Lecturer in English) and writer and psychoanalystAdam Phillips, these essays by distinguishedwriters from diverse fields explore how the ideaof interruption constitutes our sense of ourselves,often without our noticing. Contributors includeJoan Acocella, Gillian Beer, George Benjamin(KC 1978) Victor Burgin, Stanley Cavell, MaudEllmann (KC 1972), Marjorie Garber, GabrielJosipovici and John Wilkinson.The Book of Interruptions. David Hillman andAdam Phillips. Oxford. Peter Lang, 2007.Christian Muslim ForumA three-dayconference, FaithCommunities ina Civil Society Christian and MuslimPerspectives, washeld in King’s inSeptember, sponsoredby The ChristianAdnan Abidali andMuslim Forum, andJonathan Chaplinorganised by King’sgraduate student, Saira Malik (KC 2003).The Dean, Ian Thompson (KC 2005), invitedRowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterburyand Professor Tariq Ramadan, Senior ResearchFellow at St Antony’s College (Oxford) to givepublic lectures in the Chapel. The Dean said:“The two lectures are the public face of whatwill, we hope, be an important dialogue betweenvarious people involved in the field.”Saira Malik's research is on the history ofscience and ideas in the classical and medievalArabic tradition.Rus in urbsThere has been newenthusiasm for the useof England’s urbangreen spaces for theraising of cattle. And,perhaps inevitably,some of the creatures– which one hadconsidered simply tobe attractive additions to the landscape – havefound their way onto Cambridge dinner tables. Iam reliably informed that King’s, which has hadits own picturesque small herd for some time(White Park cattle, to match the Gibbs building– not these cheeky Country Life poseurs) hasas yet no plans to make a meal of them. Butclimates do change. college newsProfessor Peter Lipton3

Parade Profile: Megan Vaughan parade profile: Professor Megan VaughanPHOTO: W. NOWIKOWSKIMegan Vaughan (KC 2003) is Smuts Professor of CommonwealthHistory and a Fellow of the British Academy. She has carriedout extensive field and archival research in Malawi, Zambia andMauritius. She tells Alison Carter about her work.4Creating the Creole Island: slavery in eighteenthcentury Mauritius brings to life the complexways in which a completely new societywas formed on the once-uninhabited island(then called Île de France). Megan providesclose readings of the fine human detail fromlegal records, correspondence and travelaccounts. The island went within a lifetimefrom being a slave destination to being itselfa place of origin. As she documents theincreasingly slippery definitions of freedom,race and ethnicity in use before and afterthe French Revolution, she reflects backsome of our contemporary concerns aboutmulticulturalism and identity.Megan Vaughan’s work has centred onthe social history of rural communitiesand their responses to slavery, famine,disease and labour migration, and hasalways involved oral historical research. “Ifsomeone tells you that the goats sold by afamine victim changed into snakes whentheir new owners took them home,” sheasks, “what weight do you give this kind ofinformation?” This kind of question is herbread and butter. Although she deals withslavery, famine and disease – her accountsof these several grim reapers always havehuman voices.We are talking in Megan’s study – herrooms are in one of the medieval buildingsbehind the façade of King’s Parade, allnarrow doorways, sloping floors, steep stairsand twisted timbers. I’ve just been readingher moving new book about slavery inMauritius, with its detailed reporting of thefears of slaves and traders, and I feel I’m atsea in an old wooden ship.She deals head on with the slave trade andits economic preoccupations with mortality.In assessing the evidence for contemporaryattitudes, she turns to a revealing account byM. Brugevin, the captain of the French slaveship Licorne in 1787. Reporting on the causesof mortality (to a member, incidentally, ofthe anti-slavery lobby in Paris), he says thatthe real cause was not so much the terribleand prevalent dysentery as a very particularkind of fear. “What is most detrimental is the prejudice, inculcated in them sincechildhood, that the whites come to theirshores to abduct them, to take them totheir own land in order to eat them andto drink their blood.” This belief, he says,led to slaves literally dying of fear. But,Megan contends, the slave trade really was abloodsucking enterprise.“In East and Central Africa there’s a longstanding trope, which is that rich peopleare sucking blood out of poor people,” sheexplains. People literally think the blood isbeing sucked out of them. “When you ask,

The book is subtitled, Gender and Famine in Twentieth CenturyMalawi, and it was through gathering oral history that thegender dimension came out. “Women were saying thingslike, ‘Oh, that was the year when all our husbands left’. And Ididn’t know about that.” She then addressed what she saw asShe talks about Malawi with deep familiarity and fondnessthe gap in the ‘entitlement theory’ of famine. Nobel laureate– she taught at the University there for several years afterAmartya Sen’s Poverty and Famines (1981) was and is still verydoing her PhD (on slavery in the 19th century) and has keptinfluential. “If you can have a famine in a place where there’sup her connection. But her first contact with Africa was asactually plenty of food around, what you have to understand isa school leaver –she did VSO in Swaziland. She grew up inhow people access that food – how do theyLondon and Surrey, attending a girlsgain their ‘entitlement’ to food. What thesegrammar school and then Atlanticwomen were saying to me was that men andCollege in Wales. Her father was a“If"If you can have a famine inwomen had different ways of getting accesslocal government officer from Southa place where there’s actuallyto food and that in a crisis, women wereWales, her mother from the East Endparticularly vulnerable because men hadof London, and she and her sister theplenty of food around, whatmore access to the wage economy. Womenfirst in the family to go to university.you have to understand iswere more tied to their home and children“There wasn’t much scope for doingand less mobile, and marital relationshipsAfrican history at the Universityhow people access that foodwere fragile.” Megan’s working definition ofof Kent!” she laughs. “So I did– how do they gain theirfamine is thus a more social one. “Peoplemedieval history but worked closely‘entitlement’ to food."themselves say ‘this was a period when wewith anthropologists.” In 1986 shedidn’t behave normally’. What was strikingbecame Rhodes Lecturer and then, inthen, and it’s the same today – when there’s1996, Professor of Commonwealthbeen a crisis, especially in rural areas, whereStudies in Oxford. She remains anthere are very strong social and economic obligations – is theEmeritus Fellow of Nuffield College. “My work has been shapedreal shame and anxiety people feel when they’ve been unableby Malawi – because it’s one of the poorest and most ruralto fulfil those obligations. People feel very, very unhappy. Incountries in Africa, I ended up working on poverty.” Megana famine crisis, people do things they wouldn’t otherwise do,has been a trustee for Oxfam, sat on an advisory committeeincluding abandoning elderly people and children, or sellingworking on food, land and gender issues and was involved intheir children.”the work of The Commission for Africa, which reported in2005. Her work has dovetailed with and informed evolvingShe had personal experience of the famine in Malawi in 2002.academic discourses and public perceptions of poverty and“The first sign I saw of it was a whole calendar year earlier.famine, its causes and cures.People were queuing to buy bran, which is used as a filler ifyou don’t have anything else. It was a sign that something“There was a period in the 1970s when Africa was a seen aswas wrong.” As a European, was it hard to find food? “No, no,continent in a crisis of food production. Now that work isthere’s food around, but if you’re poor you can’t get hold of it.”being heavily critiqued for misrepresenting what was actuallyShe thinks the corruption problem is insoluble for as long asgoing on.” Politically it matters whether you say there’s a foodAfrican countries are so dependent on aid. “Any mechanismshortage or a famine. You can cover it up – or decide to call itof accountability is intercepted by the aid economy. In thea crisis and try and attract attention to it. And then, she asks,Malawi famine, some politicians hoarded food and then soldfor it to be called a famine, do people have to die in largeit at very high prices. It was corrupt – this was the nationalnumbers? Now, with the HIV/Aids crisis, it’s almost impossiblegrain store. But on the other hand the IMF had been tellingto distinguish a famine death from another kind of death. “Thethe government to sell some of it, because they thought theyimages we have come out of the big famines, mostly politicallyshould be operating the grain store as a market institution.constructed, in the Horn of Africa, with camps and peopleNow the international agencies blame the politicians and thestarving and dying of disease. The famine in Malawi is muchpoliticians blame the IMF.”more typical – no big camps, no food aid until late in the day,no people congregating so you don’t see lots of emaciatedMegan is closely involved in the Centre for African Studiesdying people because they are at home, that’s where they die. Ifin Cambridge, an interdisciplinary centre supporting Africanyou’re really ill and sick you stay at home.”institutions with a visiting scholar programme, and her currentresearch includes an AHRC project with Goldsmith’s CollegeShe wrote The Story of an African Famine, in 1987. I read it theon the history of death in Africa. She’s also just given a paperweek the report on the UK’s obesity epidemic was published,on the history of romantic love in Africa. “Not,” she laughs,bringing home the fact that obesity and famine are relative“that it was necessarily any less depressing!”terms. The fieldwork had been interesting but not terribly easy.“The government of the time in Malawi was a dictatorship andwww.african.cam.ac.ukparade profile: Professor Megan Vaughanthe fiction was that no-one was ever hungry.” She was followedaround by special branch, monitoring her interviews. “I wouldask ‘Have there been any famines since 1949?’ And peoplewould say yes, yes! But then others would chip in and say no,no – you’re not supposed to say that!” now, who is sucking the blood, people say it’s agents of thegovernment, but that they’re not sucking it for themselves butto send to Washington DC in a pipeline.” In the Malawi villageswhere she was working recently a young man appeared with apin prick in his arm saying that people had come in the night,drugged him and taken his blood. “The village headman madea fuss and the government was forced into making a statement,saying rather comically, ‘No self-respecting government couldsuck the blood from its people’.”5

The road to AgadirTen years ago, former Chaplain Patrick Magee (KC 1934) took up the offer of a Moroccan friend to live en famille inAgadir. He reports on a very successful retirement option.My friend suggested that rather than livingalone, I join his family, and for the last tenyears I have lived with them in Agadir formost of the time, returning to England nowand then. Agadir is a vast industrial city andport (with a population about that of Leeds),but has a coastline of 5 – 6 miles withexcellent beaches, which is a tourist resort.People are friendly and warm hearted, andhospitable to strangers. Their great virtue isfamily solidarity, a valuable way of life whichin Britain is in decline! A foreigner is presentedwith no great difficulties as the differences betweenpeople of different cultures are minimal. You need toknow how people are thinking and feeling and fall inwith their customs naturally. The main differenceslie at meal times. Food is usually cooked on thetagine system, meat and vegetables cooked togetherin a dish out of which we all eat. Instead of knivesand forks, crusts of bread are used by which youcan scoop up the juices with your fingers. (Knivesand forks are offered to foreigners!) Our main dietis fish (straight from the sea) vegetables and fruit– very healthy. Islam also lays much emphasis onhospitality. Friends or relatives arriving at the housewill always be given a meal or a bed – at any hour ofthe day or night!Patrick Magee (KC 1934)Tile Panel, Tunisia, XVIIIth CenturyPresented by Professor Michael Jaffé (KC 1948) inmemory of his father Arthur Daniel Jaffé (KC 1899)Snooker for intellectuals?Tom Banfield (KC 1962) traces his interest in croquet back to his studentdays. He makes the case for taking it up again in retirement.Most Kingsmen will have enjoyed half-remembered afternoons andevenings on the croquet lawn (and sometimes even mornings in theLong Vac), surrounded by the delightful sights, sounds and scents of theFellows’ Garden. I played purely socially when at King’s, and was neververy good, but I always knew it was a game I could appreciate at greaterdepth if I ever got the chance.Two particular memories stand out from the 1960s.The first was whenthe Visitor, the Bishop of Lincoln, had come to College in some importantceremonial role – and I was one of those inveigled into playing a shortgame of croquet doubles with him after dinner. He was dressed to killin a frock-coat and gaiters (sic), and looked as though he had just comehot-foot from Barchester stopping only to pose for a Punch cartoon. Alashe was not as good a player as he imagined, though that did not preventus complimenting him on his skill: “Oh good shot, my Lord!”My second memory was of watching Keith Wylie (KC 1963), aWykehamist mathematician a year or two younger than me, practising his6The population of the country is two thirds Araband one third Berber; but you cannot tell thedifference. They are strongly Muslim (Sunni). Islamis evident, with mosques being more prevalent thanchurches in a modern western city; but it is in noway oppressive. Islam is most noticeable duringthe month of Ramadan, which is very strictly kept– no food or drink must be taken between the hoursof sunrise and sunset. During Ramadan, I jointhe family at their breakfast at 7 pm, which is mysupper; thereafter I am given a full midday mealseparately; and then sleep several hours!The Moroccans are a proud people with a longhistory of independence, for they never came undereither the Byzantine or Ottoman Empires – andthus have no ‘hang-ups’. The only foreign intrusioncame with the French who administered the countryfor some forty years (but never actually occupiedit), and are generally popular. Morocco is a goodbridge between the West and the Middle East; andI feel that the more people from both sides of thecultural divide can meet the less suspicion and moreunderstanding there will be.Patrick Magee (KC 1934), a Choral Scholar, read History.Chaplain of King’s from 1946 – 1952, he was Vicar ofKingston upon Thames, Chaplain at Bryanston, TeamVicar of Bemerton near Salisbury from 1973 – 84 and laternon-residentiary Canon of Salisbury Cathedral.croquet single-mindedly and with superb skill. It was only when I tookup the game again a third of a century later (after a very satisfying ICIcareer) that I found out what an impact Keith had had. In his day he wasthe Tiger Woods of world croquet, setting new technical standards thatlater players have had to emulate or fail. He was the world championseveral times, and his book Expert Croquet Tactics is still in print. Sadly hedied at an early age.Croquet has been described as “snooker for intellectuals” – albeit from allwalks of life. I for one enjoy the peculiar combination of the physical skill,demanded by accurate hand-eye coordination, with the mental planning,necessary to build a successful break and make several hoops in one turnon the lawn. And I do appreciate the fact that the ball is stationary whenI hit it! The sport has enjoyed a recent resurgence following the unwittingpublicity given it by the former Deputy Prime Minister. A high proportionof active players are retired graduates. Britain is the current worldchampion, having taken particular pleasure in beating Australia 19-2 alongthe way.I do urge retired Kingsmen (and women too) to consider revisitingtheir youth, as I did, and join a local croquet club. Many U3A groupsrun introductory sessions. You are assured of a warm welcome, and achallenge you will relish, so do contact www.croquet.org.uk to find outwhat is available in your area.

Ivon HitchensIn this definitive study of Hitchens’life and work, Peter Khoroche (KC1965) who knew Hitchens well, drawson the painter’s published writings,correspondence and conversation tocreate a critical reappraisal of his theoryand practice. Ivon Hitchens (1893-1979)is widely regarded as the outstandingEnglish landscape painter of thetwentieth century. His work, immediatelyrecognizable by its daring yet subtle useof colour and brushmark to evoke thespirit of place is to be found in publicand private collections throughout theworld. J.M.Keynes bought three of hispaintings, which now hang in King’s.Khoroche charts the journey fromconventional beginnings to ‘figurativeundermine good corporate governance,undercut security and the prospectsfor democracy. “For over a dozen yearsmy work has put me in positions whereI could observe both bribe-seekersand bribe-payers at close range.” Shepresents accounts of major public-sector(government)bribery, and of‘gift giving’ – beit fur coats,moon cakes orgoats. She thensurveys currentefforts toreduce briberyand makessuggestions forhow to restoretransparency, concluding optimistically:“Surely this is the century in which the toleration of bribery will come to an end,the way the toleration of slavery came toan end in the nineteenth century.”Alexandra Addison Wrage is the Directorof TRACE International, a non-profit, antibribery business association.www.TRACEinternational.orgCan a Robot be Human?abstraction’, and surveys the entireoeuvre, still-lifes, flower pieces, nudes,interiors and large-scale murals besidesthe landscapes, a huge legacy of workspanning sixty years. This revised andenlarged edition contains a new selectionof over 100 colour images.Ivon Hitchens. Lund Humphries, 2007. 35.00.Peter Khoroche is also the author ofBen Nicholson: Drawings and PaintedReliefs. Lund Humphries, 2002.Bribery and extortionThose who traffic in people, narcotics, andillegal arms pay immigration officers notto ask, customs officials not to inspect,and police officers not to investigate.Alexandra Wrage (KC 1988) draws onher work before and after studying Lawat King’s, and as international counsel fora major American aerospace company,to document bribe solicitation, collusionand resistance, showing how bribesIn this book ofpuzzles andparadoxes, PeterCave (KC 1972)introduces someof life’s mostimportant questionswith tales and tallstories, reasonsand arguments, common sense andbizarre conclusions. From how to get toheaven, to speedy tortoises, paradoxesand puzzles give rise to some of themost exciting problems in philosophy– from logic to ethics and from art topolitics. Illustrated with quirky cartoonsthroughout, the book takes the reader ona taster tour of the most interesting anddelightful parts of philosophy. This title isfor everyone who puzzles about the world.“If it doesn’t make you think, you’reprobably dead already.”Peter Cave teaches Philosophy at CityUniversity, ymondcave@aol.comBooks about King’sThe Bloomsbury BallerinaJudith Mackrell tells the storyof the splendidly unpredictableRussian dancer, LydiaLopokova, who ruffled thefeathers of the Bloomsbury setand became the wife of JohnMaynard Keynes.Judith Mackrell, the Guardiandance critic, gave a talk aboutLydia Lopokova to King'smembers at the KCA Day in 2005.The Bloomsbury Ballerina.Judith Mackrell. Weidenfeldand Nicolson, 2008. 20.00.Bloomsbury & British TheatreTim Cribb tells the story of the influence of The BloomsburyGroup on English theatre through the Marlowe Society. RupertBrooke (KC 1906) was an early member and his friendshipswith Virginia Woolf and Lytton Strachey linked the new Society toBloomsbury; links were developed by George “Dadie” Rylands(KC 1921), who directed productions from 1929 to 1966. JohnMaynard Keynes (KC 1902) built the Cambridge Arts Theatrein 1936, which was managed by Rylands. This is the theatre thatPeter Hall haunted as a schoolboy and acted in as a student, inproductio

of Music, Stephen Cleobury, took the Choir to the Istanbul Music Festival in June have provided an excuse to show you some King's Islamic artefacts as well as to juxtapose one iconic building with another. (King's Chapel, completed in 1547, took over a hundred years to build; the Blue Mosque, completed in 1616, took less than ten )