Transcription

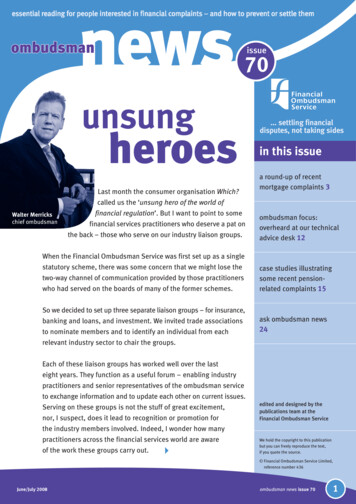

Ombudsman newsessential reading for people interested in financial complaints– and how to prevent or settle themissue 79page 3Complaints involvingcar financepage 14The Ombudsman in theHighlands and IslandsWalter Merricks, chief ombudsmanMotor ManThe love affair between the great British public and carsprovides the backdrop to a substantial proportion of ourcaseload – and in this issue of Ombudsman news we presenta fairly typical selection of complaints we have dealt withrecently involving motor cars.The consumer’s amorous relationship is with the vehicle, not with thefinance firm or insurer that makes its use possible or safe. When hopesare dashed and hearts are broken, acrimony develops and complaintsfollow. We should not, therefore, be surprised about the emotion thataccompanies them.Complaints about the settling of car insurance claims have alwaysfeatured in the ombudsman’s casebook. Disputed valuations of writtenoff vehicles, together with concerns over the quality of repairs carriedout by or on behalf of insurers, form a steady and rising workload. 4September/October 2009 – page 1page 20Motor insurance – disputesabout the quality of repairsand the non-disclosure ofvehicle modificationspage 24the Q & A page

The trend has been for insurers to take charge of repairs rather than leavingconsumers to arrange the repairs themselves and then claim for the cost.But does that account for some of the increase in our complaints in this area– from 2,500 in 2005 to over 6,200 last year?Our jurisdiction over consumer credit has brought additional complaintsabout car finance businesses or the extent to which that they should beresponsible for the quality of vehicles for which finance is provided.And many of the complaints we receive about payment protection insurancerelate to cover for loans taken out in order to buy a car.Our remit only covers the financial aspect of people’s relationship with cars.But complaints about second-hand car sales, and car servicing and repair,are among the top five categories of complaints to Consumer Direct.Consumer bodies point out that there’s no ombudsman for most of thesedisputes. Will there perhaps be a Motor Ombudsman one day?Walter Merricks, chief ombudsmanswitchboard020 7964 1000consumer helpline0845 080 1800 or 0300 123 9 123open 8am to 6pm Monday to Fridaytechnical advice desk020 7964 1400South Quay Plazaopen 10am to 4pm Monday to Friday183 Marsh WallLondon E14 9SRwww.financial-ombudsman.org.ukSeptember/October 2009 – page 2 Financial Ombudsman Service Limited.You can freely reproduce the text,if you quote the source.Ombudsman news is not a definitivestatement of the law, our approach or ourprocedure. It gives general information onthe position at the date of publication.The illustrative case studies are based broadlyon real-life cases, but are not precedents.We decide individual cases on their own facts.

case studiesComplaints involvingcar financeThe coverage of the ombudsman service was extended in April 2007 to includeall regulated consumer credit activity. Since then we have seen a steady increasein the number of complaints made to us about car finance. Most of thesecomplaints concern hire purchase, although some involve leasing agreementsor loans taken out through car dealers.We are able to consider complaints about car dealers as well as those aboutcredit or hire businesses – but only in relation to their consumer credit activities.For dealers, that will usually be credit broking; for the credit or hire businessesit will be hire purchase, lending or leasing.Hire purchase is a type of financial arrangement where the consumer makes amonthly repayment for a set period of time, during which the car remains theproperty of the hire purchase business. At the end of the period, the consumercan either hand back the car, or pay a further lump sum (often called a ‘balloonpayment’) to buy the car outright.Consumers frequently find the technicalities of hire purchase transactionsconfusing. Typically, they believe they simply went to a dealer and bought a carwith the aid of credit, when what actually happened is rather different: they chose a car, and asked the dealer for credit to help them pay for it; the dealer acted as a credit broker, arranging hire purchase throughanother business;September/October 2009 – page 34

case studiesComplaints involvingcar finance the hire purchase business bought the car from the dealer, and thenprovided it to the consumer under a hire purchase agreement – so the caris owned by the hire purchase company (not the consumer).Hire purchase agreements are covered by the Supply of Goods (Implied Terms)Act 1973. This says there are implied conditions in a hire purchase agreement,including a condition that the goods will be of satisfactory quality and will be fitfor purpose. (Implied conditions are those that can be assumed to be includedin the agreement, even if they do not actually appear in writing.) So where aconsumer has a complaint about faults in a car that was bought by means of a hirepurchase agreement, we can consider the complaint if it has been made againstthe hire purchase business. We are not able to pursue such complaints if they aremade against the dealer. This is not just because the selling of cars is not a consumercredit activity but because, under a hire purchase agreement, the dealer doesnot sell the car to the consumer. In our experience, some businesses encourageconsumers to complain to the dealer in these circumstances, which adds to theconsumer’s confusion. This is what happened in case 79/4 below.Another form of car finance that features fairly regularly in the complaints we seeis the type of loan that is often called a ‘fixed-sum loan’. Here the dealer acts as acredit broker and – at the time of the sale – arranges the loan for the buyer from aseparate business – the lender. The lender pays the proceeds of the loan direct tothe dealer and the consumer makes regular repayments to the lender.When this type of loan is used to buy the car, then under Section 75 of theConsumer Credit Act 1974 the lender may, in some circumstances, be equally liablewith the dealer if something is wrong with the car. Most commonly, that will bewhere the dealer seriously mis-describes the car, or where the car has faults of aSeptember/October 2009 – page 4

case studieskind that amount to a breach of contract by the dealer. Even where the car issecond-hand, it must still be safe and in appropriate condition for its age andprice – as we see in case 79/2.In these sorts of cases, we will explain to the consumer that the complaintmust be brought against the business that provided the hire purchase orfixed-sum loan, and that is therefore responsible for the quality of the carprovided (under the hire purchase agreement – or through Section 75if the credit was a fixed-sum loan).Lenders and hire purchase providers are sometimes reluctant to lookproperly into a consumer’s complaint about faults in a car, and prefer to takethe dealer’s word for it that the car was in good condition when it was supplied.However, we would expect them to take reasonable steps to satisfy themselvesin the matter, before they decide whether or not to uphold a consumer’s complaint.Sometimes the complaint is about the activity of credit broking, and sois properly brought against the dealer. As car dealers are covered by uswhen they carry out credit broking, they need to be prepared to answer ourquestions about any complaints that are brought to us.Where we uphold a consumer’s complaint, we are able to consider a range ofpotential measures when deciding on an appropriate settlement. These couldinclude refunds, compensation, replacement vehicles or the early terminationof a credit agreement, without charge. Our aim is to bring about an outcomethat does justice to the individual case, taking account of what each partydid (or failed to do).September/October 2009 – page 54

case studiesComplaints involvingcar financeConsumers, as well as consumer credit businesses, should take care to actreasonably during the dispute. Hiding or abandoning the car, or damaging it,for example, will just make a difficult situation worse (as in case 79/3).As always, it is important for businesses to keep proper records in case acomplaint is made against them. The business complained about in case 79/5was able to produce contemporaneous photographic evidence to support itsclaim that the car had been damaged. This was particularly helpful in enablingus to make our own independent assessment of the nature of the damage.The following case studies illustrate some of the complaints that we have dealtwith recently involving car finance.n 79/1Unfortunately, the problems with the roofconsumer attempts to cancel agreementcontinued. Miss Q returned the car forwhen car bought on hire purchase turnsrepairs on five more occasions over theout to be faultynext three months. On the final occasion,the dealer kept the car for nearly a monthA call-centre supervisor, Miss Q,before returning it to her.obtained a brand-new hatchback withthe help of hire purchase arranged byBy then, she had given up hope thatthe car dealer. Only a couple of weeksthe problem would ever be resolved.after taking delivery of the car,She wrote to the hire purchase businessshe found that a significant amount ofand said it appeared to be impossiblerainwater had leaked through the roof.to obtain an effective – and permanentShe took the car back to the dealer,– repair to the roof. As she had alreadywho repaired it and returned it to hergiven the dealer ‘a fair chance to putthe following day.things right’, she felt she was now‘entitled to cancel the agreement andhand the car back’.September/October 2009 – page 6

The faulty roof and the frequent needresponded by telling her it was unablefor repairs meant that her use of the carto help as it was ‘a finance company,had been limited and far from trouble-not a garage’. After she had pursuedfree. So we said the hire purchasethe matter for some weeks, it eventuallybusiness should retain just 50 from eachtold her it was prepared, ‘as a goodwillof the monthly repayments Miss Q hadgesture’ to liaise between her and themade. It should return the rest of thedealer to help her get the car repaired.money to her, plus interest. We said itMiss Q did not think this an acceptableshould also pay her 200, in recognitionoption, but the hire purchase businessof the inconvenience caused by its poorrefused to discuss the matter further.handling of her complaint.nShe then brought her complaint to us.n 79/2complaint upheldWe were satisfied, from the reports theconsumer asks to cancel loandealer had provided, that there was aagreement after discovering majorsubstantial and seemingly irreparablefaults in car bought with the loanproblem with the roof of the car.We agreed with Miss Q that a faultA retail manager, Mr B, bought aof this nature was unacceptable in asix-year-old car with the aid of abrand-new car – and that she had givenfixed-sum loan, arranged by the carthe dealer ample opportunity to try todealer. Within two days of taking thecorrect the fault.car home, he discovered that neitherthe fuel gauge nor the speedometerWe pointed out to the hire purchasewere functioning properly and thebusiness that, under the hire purchasecooling fan did not work at all.agreement, it (rather than the dealer)He therefore returned the car towas the provider of the car – and wasthe dealer for repairs.therefore responsible to Miss Q for thequality of the car.Very shortly after getting the car back,Mr B had to take it for further repairs,In our view, the facts of this caseas there was a problem with one of thejustified Miss Q being released frompedals. And a few weeks after that,her liability under the hire purchasehe found that water had leaked intoagreement. So we said the hirethe driver’s foot-well area – and thepurchase business should cancelfuel gauge and speedometer hadthe agreement and arrange to collectbroken again.the car from Miss Q.September/October 2009 – page 74case studiesInitially, the hire purchase business

case studies. the lender said that anyproblems with the car were ‘down tothe dealer to sort out’.After that, a problem developed withsimilar value, Mr B was unwilling to takethe front brake discs and the fixings forthe risk that a replacement car mightthe driver’s seat. The dealer arrangedturn out to be of a similarly poor quality.for a mechanic to collect the car fromMr B and take it away for repairs.He told the lender he wanted to returnBut an hour before the mechanic wasthe car and cancel the loan agreement.due to arrive, Mr B rang him to say theHowever, the lender said that this wascar would have to be towed away, as itnot possible and that any problems withwould be too dangerous to drive it.the car were ‘down to the dealer to sortHe had noticed a strong smell of petrolout’. Mr B then came to us.inside the car – and petrol had leakedcomplaint upheldon to his driveway.We were satisfied, from the evidenceIt was over three weeks before the carMr B provided, that the car hadwas eventually repaired and returnedsignificant defects which the dealer hadto Mr B. For a short while all appearedfailed to put right within a reasonableto be well. However, while the carperiod of time. In the particularwas having its MOT inspection at ancircumstances of this case, we acceptedindependent garage, an electricalthat it was reasonable for Mr B to haveburning smell was detected in therefused the dealer’s offer to exchangeengine compartment, so the inspectionthe car for another used vehicle.had to be abandoned.We accepted the lender’s view thatBy then, it was nearly six months since‘some issues’ might be expected toMr B had bought the car. Its existingcome to light with a second-hand carMOT certificate would shortly run out.of this age. However, it seemed toHe had lost faith in the dealer’sus that the ‘issues’ in this case wentability to carry out lasting repairs.beyond what Mr B might reasonablyAnd although the dealer had offered tohave expected to encounter, given theexchange the car for another used car ofcar’s age and price.September/October 2009 – page 8

certificate in its current state.consumer asks to cancel agreementThe problems had started to becomebecause car being bought on hireapparent very shortly after Mr B hadpurchase was faultybought the car – and they were welldocumented. So it seemed likely thatMr G’s local car dealer arranged hirethe car had been faulty at the time itpurchase to enable him to buy awas sold – and that there had thereforetwo-year-old used car. Three monthsbeen a breach of contract.later, Mr G told the dealer that the carkept breaking down, so he wanted toBecause of the type of loan he hadreturn it and cancel the hire purchasetaken, Mr B was able (under Section 75agreement.of the Consumer Credit Act 1974)to claim against either the dealer orThe dealer insisted that it was unablethe lender for the breach of contract.to help, as there was nothing wrongwith the car. Mr G then decided toThat meant the lender was liable forcancel the direct debit for his monthlyMr B’s losses in the matter. We saidhire purchase payments.it should release him from the loanagreement and that – for each monthThe hire purchase business contactedwhen the faults had prevented himhim a few weeks later to ask why hefrom using the car – it should refund hishad missed a payment. He said he wasrepayment. We said the lender shouldnot prepared to continue paying foralso pay Mr B 200, in recognition ofa ‘faulty car’ and that he would handthe inconvenience caused by its poorit back as soon as the hire purchasehandling of the complaint.agreement was cancelled.nThe hire purchase business said that. he said he was not– as a first step – it would get the carinspected to establish exactly what wasprepared to continue payingwrong with it. But Mr G was adamantfor a ‘faulty car’.that the agreement must be cancelledbefore he would hand over the carto anyone.September/October 2009 – page 94case studiesn 79/3The car would not obtain an MOT

case studiesThe business again explained that itSo we said there did not appear to becould not know how best to proceedany reason why he should be releaseduntil the car had been inspected.from the hire purchase agreement.Mr G then locked the car in a friend’sWe did not uphold the complaint.garage. He later told us this was toWe told Mr G he should consider carefullyensure the hire purchase businessthe potential consequences of keepingwould not be able to find the car if itthe car hidden and continuing totried to take it away.withhold his payments.Unable to reach any agreement with thenn 79/4business, Mr G eventually brought hisconsumer asks lender to pay for repairscomplaint to us.when the used car bought with a loan isfound to be faultycomplaint not upheldMr G told us that as he was ‘notA trainee hairdresser, Miss W, took outparticularly knowledgeable about cara fixed-sum loan so she could buy aengines’ he could not tell us exactlythree-year-old used car. While she waswhat was wrong with his car.driving the car home after collectingAnd although he gave us a list of theit from the dealer’s, she heard a louddates when he said the car had brokennoise in the engine and then noticed adown, he was unable to offer anylarge quantity of black smoke comingevidence to back this up. He said he hadfrom the exhaust.not used a breakdown service but, oneach occasion, had arranged for a friendShe took the car straight back and wasto help him out by towing the car home.assured by the dealer that all would bewell once he had arranged for the fuelWe thought the hire purchase businessinjectors to be cleaned.had acted reasonably in saying itneeded to get the car inspected beforeInitially, this seemed to solve theit could decide how to proceed. Mr Gproblem but a few weeks later the carhad not helped the situation at all bybroke down altogether. Rather thanrefusing to cooperate with such angoing back to the dealer, Miss W hadinspection and by then moving the carthe car assessed by a local garage.to an undisclosed address.She was told that new fuel injectorsWe saw no evidence that he had beenwere needed, at a total cost ofprovided with a faulty car, and he wasaround 1,500.unwilling to allow anyone to inspect it.September/October 2009 – page 10

case studies. she heard a loud noise in the engine,then noticed a large quantity of blacksmoke coming from the exhaust.When she asked the lender if it wouldThe lender said it was unable topay for this work, it said it would firstcomment until it heard from the dealer.have to arrange its own inspection ofShortly after that, the dealer rangthe car. This was carried out severalMiss W, offering to exchange her carweeks later and confirmed the need forfor one that he said was of a similarnew fuel injectors. However, the lenderage and value and had only just cometold Miss W not to get the car repairedinto his showroom.before it had obtained the dealer’scomments on the car’s condition.Miss W wanted to keep her existing carbut to have it properly repaired.Over the next few weeks, Miss W rangThe dealer told her that was not anthe lender at regular intervals to askoption. And when she contacted thewhat was happening. Each time,lender, it said it was not prepared tothe lender said it was still waiting to hearpay for repairs as she had now beenfrom the dealer. Miss W made severaloffered an alternative car.attempts to contact the dealer herself,but her calls were never returned.Miss W then complained to us aboutboth the lender and the dealer.Eventually, she sent the lender a letterof complaint. She said that travellingcomplaint upheldto and from work was difficult andWe told Miss W that we would onlyexpensive without the use of her car.be able to look into a complaint aboutShe did not want to delay the repairsthe dealer if it concerned his regulatedany longer – but could not afford toconsumer-credit activities. The relevantpay for them herself unless the lenderactivity in this case was credit-brokingconfirmed that it would refund the– but there was no suggestion that thecost of the work.dealer had done anything wrong whenarranging Miss W’s loan.September/October 2009 – page 114

case studies. we did not accept his view thatthe business had ‘forfeited its right’to pass on the cost to him.We were, however, able to look into hern 79/5complaint against the lender becauseconsumer disputes repair bill afterthe type of loan she used to buy the carreturning car at the end of three-yearmeant she was covered by Section 75 oflease periodthe Consumer Credit Act 1974.Mr D leased a sports car under aIt was clear, from the inspectionsthree-year regulated consumer hirethat both Miss W and the lender hadagreement, which allowed him to drivecommissioned, that the car had beenthe car for up to 8,000 miles each year.sold with a major fault.One of the conditions of the lease wasthat he was liable for the cost of anyWe contacted the lender and explaineddamage to the car beyond ‘normal wearwhy, given the circumstances of thisand tear’.case, we thought it should pay tohave the car repaired. It agreed toWhen the lease period came to ando this, and to give Miss W 500 toend, he returned the car to the leasingcover her out-of-pocket expenses andbusiness with 18,162 miles on thecompensate her for the inconvenienceclock – well under the maximumshe had been caused.mileage he was allowed.n. he was liable for the cost ofany damage to the car beyond‘normal wear and tear’.Soon afterwards, the business soldthe car at auction (as is usual practice).It then asked Mr D to pay 177.50.This was the estimated cost of repairingdamage that it said had been caused tothe car while Mr D had the use of it.September/October 2009 – page 12

The business provided evidence thatbusiness that the low mileage on 177.50 represented a fair estimate forthe car when he returned it shouldthe cost of the repair work. We did not‘more than make up for any defectsagree with Mr D that his low mileagethe car might have had’.would ‘off-set’ the cost of any damage.Nor did we accept his view that –He denied that the car had sustainedin putting the car into the auctionany damage beyond what could bebefore getting it repaired – the businessconsidered ‘normal wear and tearhad ‘forfeited its right’ to pass onover a three-year period’. And he saidthe cost to him.that, in any event, the business hadleft it too late to expect him to pay, as itUnder the leasing agreement, Mr Dshould have had the car repaired beforewas liable to pay the cost of the damagesending it to auction.in question – and it was immaterialwhether these repairs were carried outcomplaint not upheldbefore or after the car went to auction.The leasing business sent us theWe did not uphold his complaint.photographs it had taken of the carwhen Mr D returned it. These clearlyshowed a large rip to the fabric of oneof the seats, as well as a cut on thenear-side rear tyre.After referring to the guidelines on fairwear and tear produced by the BritishVehicle Rental and Leasing Association(BVRLA), we said the business was rightto say the damage to the car could notbe regarded as ‘normal wear and tear’. he said the businesshad left it too late to expecthim to pay.September/October 2009 – page 13ncase studiesMr D refused to pay. He told the

The Ombudsman inthe Highlands and IslandsA small team from the ombudsman service recently spent a week in the ScottishHighlands and Islands, meeting some of our most geographically-distant customers.Working in partnership with a number of front-line consumer advice agencies,we ran a series of informal ‘complaints clinics’ for local residents, as well asorganising training sessions for community and advice workers.The tour formed part of our ongoingEstablishing partnerships with localcommitment to carrying out a wide range oforganisations formed a key part of ouractivities across the UK, aimed at sharing ourstrategy and we are grateful for theexperience and knowledge with the outsideenthusiastic support and practical assistanceworld. This includes undertaking outreachwe received from Citizens Advice Scotland,work with different local communities –Trading Standards in Scotland, Money Adviceraising awareness of our role among thoseScotland, Consumer Direct Scotland, theless likely to use – or be aware of –Highlands Council, Argyll and Bute Council,the ombudsman service.and Orkney Council. As well as helping topublicise our events, these organisationsWe targeted the Scottish Highlands and Islandsprovided us with free venues for thebecause we receive proportionately fewercomplaints clinics and training days –complaints from consumers based there thanand handled the booking of appointmentswe do from consumers in the rest of Scotland.for consumers wanting to attend our clinics.We were also aware that the Scottish Highlandsand Islands has a higher than averageSet up in the main centres of population –proportion of older residents – and consumerInverness, Kirkwall, Oban and Stornowayresearch consistently shows that awareness– the clinics offered a free 15-minuteof the ombudsman service among consumersappointment to anyone who needed helpaged 65 and over is significantly lower thansorting out a problem with their bank,among those in most other age groups.insurance company or finance firm.Intensive preparation in the weeks leading upAdvertising our forthcoming visit was quite ato the tour enabled us to make the most of ourchallenge, given that the local population islimited time in the area – and ensured that wespread sparsely over a relatively large area.generated plenty of advance publicity for ourAs well as getting prominent coverage inprogramme of events.the local and regional press – and on localSeptember/October 2009 – page 14

radio stations – we enlisted the help of localMPs, schools, libraries, doctors’ surgeries,rural post offices, churches and faith groupsin distributing our publicity materials.We designed a special set of posters andleaflets for use on the boats plying the key ferryroutes between the mainland and the islands.We also expanded the information available inGaelic on our website (shown above).and Inverness. We also ran training sessionsin dispute-resolution to community and adviceIt quickly became clear that all the effort thatworkers based in a variety of locations fromhad gone into spreading the word about ourSkye to Kirkwall. A trading standards officervisit had paid off. We had to squeeze in awho attended one of the sessions later toldfew extra slots at all our clinics, so as not tous ‘Everyone who attended the event founddisappoint anyone by turning them away.it worthwhile. As well as providing a greaterAt each of the venues we met a wide range ofinsight into the ombudsman’s role, it hasconsumers – some of whom had travelled agiven us confidence about the types of casesconsiderable distance to see us. The issueswe can refer to the Ombudsman in future’.they raised with us ranged from a query aboutthe appropriateness of advice to put lifeIn the months following the initiative, we havesavings in an investment bond to a disputenoticed a three-fold increase in the numberover the quality of repairs arranged by anof people accessing the information weinsurer on a storm-damaged farmhouse.provide on our website in the Gaelic language.And recent consumer research shows thatIn tandem with the complaints clinics,Scotland now has a higher unprompted levelwe provided complaints-handling trainingof awareness of the ombudsman service thansessions for consumer advisers in Obanany other area of the UK.JWhat’s next?Following the success of our Highlands and Islands tour, we areplanning a similar initiative in Wales in the early part of 2010.September/October 2009 – page 15

case studiesMotor insurance – disputes about thequality of repairs and the non-disclosureof vehicle modificationsAs we noted in our last annual review, motor insurance is the second mostcomplained-about area of general insurance after payment protection insurance(PPI). A sizeable number of the motor insurance complaints we see concern thequality of repairs carried out following an accident.Generally, the insurer is responsible for the quality of such work if the policy saysthat the insurer will arrange the repair – or if, in practice, this is what happens.If the policy simply offers to reimburse the consumer for the cost of the repair –and the consumer arranges that repair – then the insurer is not responsible forany failings in the quality of work undertaken.Some disputes involving motor repairs arise from disagreements about the cause ofthe damage, for example, did all the damage result from the accident (in which caseit is the insurer’s responsibility to sort it all out) – or did some of the damage comeabout because of wear and tear or an earlier accident? When deciding such disputes,we will need to consider the evidence to decide the most likely cause of the damage.Sometimes the insurer has refused to pay a claim because it says the consumerfailed to disclose that the vehicle had been modified. In such cases we look atwhat questions the insurer asked – at the time the consumer applied for thepolicy – to try to establish whether there had been any modifications to a vehicle.We will also consider whether any non-disclosure on the part of the consumer wasmaterial to the claim and the extent to which the non-disclosure was deliberate,reckless or inadvertent.September/October 2009 – page 16

motor engineer, the damage his dealermotor insurer rejects claim for repairhad rectified was not caused by theon grounds that damage resulted fromaccident but had come about through‘normal wear and tear’‘normal wear and tear’. It was thereforenot covered by the policy.Mr K‘s insurer arranged for one of itsapproved repairers to carry out someMr K strongly disputed this and theremedial

not sell the car to the consumer. In our experience, some businesses encourage consumers to complain to the dealer in these circumstances, which adds to the consumer's confusion. This is what happened in case 79/4 below. Another form of car finance that features fairly regularly in the complaints we see