Transcription

BRIEFING FOR THEHOUSE OF COMMONSJUSTICE COMMITTEEFEBRUARY 2012Ministry of JusticeComparing InternationalCriminal Justice Systems

Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely.We apply the unique perspective of public auditto help Parliament and government drive lastingimprovement in public services.The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending on behalf ofParliament. The Comptroller and Auditor General, Amyas Morse, is an Officerof the House of Commons. He is the head of the NAO, which employssome 880 staff. He and the NAO are totally independent of government.He certifies the accounts of all government departments and a wide rangeof other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to reportto Parliament on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with whichdepartments and other bodies have used their resources. Our work led tosavings and other efficiency gains worth more than 1 billion in 2010-11.

Ministry of JusticeComparing InternationalCriminal Justice SystemsBRIEFING FOR THE HOUSE OF COMMONS JUSTICE COMMITTEEFEBRUARY 2012

We have produced this briefing for the Houseof Commons Justice Committee to provide aninternational dimension to its inquiry into thebudget and structure of the Ministry of Justicein England and Wales.

ContentsIntroduction 4Part OneMaking internationalcomparisons 8Part TwoInternational comparisons ofkey crime and justice data 12(a) International trends in crime 12(b) International trends in dealingwith crime 18(c) Sentencing comparisons,including prisoner numbers 21(d) The use of remanddetention 30(e) Measuring reoffending 32(f) Wider public perceptionsof justice 34Part ThreeComparing expenditure oncriminal justice 38The National Audit Office study teamconsisted of: Anna Athanasopoulou,Stephanie Bryant, Tim Phillips andAlex Quick under the direction ofAileen Murphie, with significantadditional contributions fromJabin Ahmed, Ben Gunter,Claire Hardy, Rishi Raithatha,Callum Saunders, and Marcus Wilton.For further information about theNational Audit Office please contact:National Audit OfficePress Office157–197 Buckingham Palace RoadVictoriaLondonSW1W 9SPTel: 020 7798 7400Email: enquiries@nao.gsi.gov.ukWebsite: www.nao.org.ukTwitter: @NAOorguk National Audit Office 2012Appendix OneKey facts about comparatorterritories 43Appendix TwoMethodology 44Endnotes 46

4Introduction Comparing International Criminal Justice SystemsIntroduction1We have produced this briefing for the House of Commons Justice Committeeto provide an international dimension to its inquiry into the budget and structure of theMinistry of Justice in England and Wales. The briefing compares crime and criminaljustice data from a number of different countries and sets out some of the challenges ofmaking such comparisons. It also identifies a number of areas where it may be beneficialfor the Ministry or others to do additional comparative work.2The briefing focuses on two main types of information. First, there are quantitativeanalyses of published criminal justice statistics, including data about crime, the courtsand prison systems in a number of countries. Secondly, there are reviews of a smallselection of recent academic literature on criminal justice subjects, which we looked at inorder to provide Committee Members with some insights into the directions being takenin current research.3In neither case was our analysis intended to be exhaustive. But, in order toinform our approach, we interviewed a small number of criminal justice experts,including analysts at the Ministry of Justice, about international comparisons of criminaljustice systems. We also drew on our experience of making and using internationalcomparisons in our value for money studies on home affairs and justice and on a briefingsimilar to this one which we published following a request by the Home Affairs SelectCommittee in 2003. We have not examined specifically how the Ministry of Justice usesinternational evidence to inform its internal decision-making. Our main aim in puttingthis briefing together was to demonstrate how, caveats notwithstanding, much valuableinformation can be extracted from existing criminal justice data and many more usefulanalyses might be performed.4Among the material we reviewed are published documents from national justiceand interior ministries and statistics authorities; reports from criminal justice think tanksand academic criminologists; and analyses by major international bodies, such as theUnited Nations and the Council of Europe.5Experts in this field will already be aware of many of the limitations in our analysis.These are caused by incompatibilities in the ways that countries measure crime andpunishment. We describe these incompatibilities in depth in the body of our report, andhave attempted to minimise the impact they have by choosing carefully the countries wecompared and the analyses we carried out.

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Introduction56We selected a range of advanced democratic nations for our detailed work,including some common law and non-common law jurisdictions, countries from theEuropean Union and the Commonwealth, and some with reputations either for liberal orpunitive justice systems. To enhance our understanding of the United States of America,for which only limited data are available at the federal level, we also included the state ofCalifornia within our analyses. Accordingly, this briefing focuses on: England and Wales; Northern Ireland; Scotland; Australia; Canada; New Zealand; the Republic of Ireland; the United States; the US state of California; Finland; France; and the Netherlands.A summary of some key factual information about each of these places can be found atAppendix One, while further information about our methods and a list of the people weconsulted, are at Appendix Two.7This report is ambitious in scope and consequently in the breadth of issues itraises. Overall, we believe that it shows the importance of international comparisonsand the potential they have to improve the value for money of criminal justice systems,including that of England and Wales. At a time of global fiscal restraint, it is tempting forgovernments to cut back on research and analysis, especially when the results may beonly partial or hard to interpret. International comparisons seldom provide answers ofthe ‘silver bullet’ variety, but the comparative dimension can provide valuable informationabout how politicians in different countries tackle similar problems and about longterm trends that require explanation. International comparisons can, however, be veryresource intensive and take time to deliver results.

6Introduction Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems8Overall, we found that the Ministry of Justice had an admirable record of producinghigh-quality and timely statistics about the criminal justice system in England and Wales.None of our comparator countries had a more comprehensive or up-to-date set of data.Like justice departments in other countries, however, the Ministry of Justice here hastraditionally focused research on domestic issues rather than international comparisons,albeit while contributing fully to projects run by international bodies such as the UnitedNations and the Council of Europe. Much of what it has done in terms of internationalanalysis has been for internal consumption, aimed at assisting in the development ofpolicy. For instance, it told us that in the last year it had produced or commissionedresearch with an international dimension on squatting, community orders, sentencingguidelines and prison policy. The Ministry did publish its international review of legal aidin 2011, and this put much useful information into the public domain for the first time; assuch, it demonstrates that even when the findings of international comparisons requirecareful handling, they can still prove compelling and worthwhile.9At a high level, this report shows that the criminal justice challenges facingadvanced nations are essentially similar. Governments are expected to put in placesystems capable of preventing crime, and where these are not effective, to developother responses to detect and punish it. All developed countries aspire to rehabilitate thecriminals they catch to a greater or lesser extent. Yet the responses to crime can varysubstantially from place to place, as do the costs of criminal justice systems and theoutcomes they achieve.10 It is beyond the bounds of this piece of work to explain all these variations, andindeed some of them are likely to be inexplicable. Nonetheless, this report indicates anumber of areas where productive further research might be carried out: either detailedstatistical and analytical research or more qualitative consultations about the approachesadopted in different jurisdictions. We understand that the Ministry of Justice is unlikelyto be able to put additional resources into such research at the present time without aclear ‘spend to save’ rationale; and even then it may struggle to do so. But we advisethat it consider carefully the additional work we are suggesting alongside its existingplans and reprioritise accordingly. Think tanks, campaigning organisations and universitydepartments may also want to consider taking some of these analyses forward.11Some of the main issues raised by this report are as follows: The potential benefit of conducting more research into prison population trendsin other countries in order to learn lessons from those with declining prisonpopulations (see page 22). The lack of evidence for a clear relationship between the use of prison andchanges in crime levels (see pages 25-26). The potential benefit of more research into international trends in reoffending, whichare almost impossible to compare at present (see page 33)

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Introduction The need for better information about the impact of police numbers and otherchanges in police activity on the recording of crime and reoffending rates(see pages 34-35). The potential for justice departments experiencing cuts to learn from one another(see pages 40-41).12The body of our report is structured as follows: Part One describes the main data sources we are using and the limitations facedby people wanting to compare them; Part Two contains a number of comparisons of operational data, for instance oncrime trends and prison numbers; and Part Three considers the costs of different criminal justice systems around theworld, and current attempts to reduce them.7

8Part One Comparing International Criminal Justice SystemsPart OneMaking international comparisons1.1 In this Part, we examine the challenges of making international comparisons in thearea of criminal justice, as well as some of the potential benefits of doing so.Using data to make policy1.2 Politicians and civil servants constantly affirm their desire to make policy on thebasis of evidence.1 This is as true in the area of criminal justice as anywhere. As wasobserved in a 2010 publication from the European Institute for Crime Prevention andControl, ‘an efficient system for the collection, analysis and dissemination of informationon crime and criminal justice is a prerequisite for effective crime prevention’.2 The idealscenario is typically taken to be one in which good data inform the initial setting of policy,while subsequent measuring of effectiveness produces new data that can inform futuredevelopments, a cycle as set out in Figure 1.Figure 1The measurement process cycleNew performance measuresand process improvementPerformancemeasuresCriminal justice dataCriminal justicedata measurementprocess cycleUpdated criminaljustice dataSource: National Audit Office analysisPolicydevelopmentsNew policies

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Part One9Benefits of international comparisons1.3 International comparisons have an important role to play in building understandingof how individual criminal justice systems are functioning. They can also help toimprove them. Each jurisdiction has a single criminal justice system, which meansthat comparative evidence about its performance can usually only be had by lookingat systems in other countries, even if this is difficult in practice. Similarly, while policyinitiatives in the justice area are sometimes ‘home-grown’, it is also common for them tobe inspired by policies overseas.1.4 This report has been produced to coincide with the Justice Committee’s inquiry onthe budget and structure of the Ministry of Justice in England and Wales. That inquiry islooking at the adequacy of the framework within which the Ministry operates at presentand at whether it is handling its finances to best effect. Although high-level, it is touchingon every aspect of the Ministry’s business, including the courts, legal aid, the NationalOffender Management Service (NOMS) and the Parole Board.1.5 Seeing these issues within an international context is important, and so the JusticeCommittee asked us to complete a review of available international criminal justice dataand report back. The NAO undertook a similar exercise for the Home Affairs SelectCommittee in 2003. The findings from our latest analyses are described in Parts Twoand Three of this report. But, overall, our observation is that international comparisonsremain a valuable tool for criminal justice policymakers, and one to which moreconsideration might be given in future.1.6 There is, of course, always much work to be done before a specific comparisoncan be made to stand up, and before its significance and robustness can beestablished. Some of the challenges of doing this are described below. The difficultiesappear to be greatest often when it comes to comparing the cost-effectiveness ofdifferent systems. However, if more effort were to be made to do this (not just by theMinistry of Justice and equivalent departments around the world but also by academicsand think tanks), it could produce useful results: for instance, evidence that could beused to inform public debates about what is worthwhile and what is not in criminaljustice policy. It was not within the scope of this exercise to produce such evidence, butthe NAO would be happy to talk to any organisations that are interested in attempting todo so in the future.

10Part One Comparing International Criminal Justice SystemsChallenges of making international comparisons1.7 The main reason why experts often hesitate before embarking on internationalcomparisons in the justice area is because they are so difficult. On the face of it, theyappear to be considerably more difficult than comparisons of other public policy issues,for instance, health. In the health arena, definitions of illnesses and lists of acceptabletreatments are relatively standard throughout the developed world: certainly more sothan definitions of crime or of specific punishments and rehabilitative techniques. Theconcept of ‘dosage’ is a good case in point. It has come into use increasingly in thecriminal justice environment in Britain in recent years, but is still a much more inexactand less measurable idea there than in the medical profession. Put simply, as theEuropean Institute for Crime Prevention and Control wrote in 2010, in the field of criminaljustice ‘the availability of internationally comparable statistics is very limited’.31.8 What impairs comparability? There are multiple factors. These should be borne inmind by readers of this report. They include: differences in the ways crimes are counted (for example, whether countries registera crime as soon as it is reported to the police or whether they do so only when it istaken up by prosecutors or associated with a named suspect); differences in offence categorisations (e.g. what is classed as a serious violentcrime), sentence types (e.g. whether suspended sentences are used or not), andreoffending measures (e.g. whether re-arrests or reconvictions are measured); frequent changes in measurement rules and definitions, which evolve as recordingpractices and laws change and as methodological improvements are made (e.g.in Australia the 2010 iteration of key crime statistics and its successors are notcomparable with those from previous years);4 and wide variation in the timeliness of data, with, we have observed, England and Walesoften being the quickest to produce their definitive statistics.1.9 Comparability issues can often be mitigated, at least partially, by careful cleaningof data or the right choice of analyses. In this report, for instance, we have concentratedon comparing changing trends in crime and punishment internationally, rather thanmaking direct comparisons betweens rates and volumes for given years. Thus, we havenot made much of the fact that New Zealand has, on the face of it, a significantly highercrime rate than France, as we cannot be sure that the two places measure crime in thesame way. Instead, we focus on the fact that the trend in both countries has been forcrime rates to fall in recent years.

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Part One11Challenges of interpreting international comparisons1.10 However, comparability is only part of the problem. Attribution – the question ofwhat is causing a given trend – can also cause difficulties for those wanting to makeinternational comparisons. This is because of the number of systemic factors that tendto be at work.5 These include: intrinsic differences between legal systems (e.g. some experts believe thatCommon Law systems, like that in England and Wales, tend to make more use ofcourt for petty crimes than systems based on Roman, or Civil, Law); fundamental differences in policy structures (e.g. many experts believe thatcriminal justice outcomes are affected by whether policy is set in one governmentdepartment or several, and by whether it is implemented directly, at arm’s length orthrough the private sector); differences in the number of laws that countries have on their statute books, andthus in the degree to which specific undesirable activities are criminalised;6 characteristics of independent sentencers and the impact of any training theyreceive or any controls exerted over them; and differences in public confidence in the police and other criminal justice agencies, andthus in the degree to which people cooperate with them and comply with the law.1.11 Away from narrow criminal justice concerns, it is also generally agreed that widersocial issues have an important impact on criminal justice problems and outcomes.Thus, disparities in educational attainment, inequalities in income and in race relationsare all now recognised as having a direct, if complex, influence on outcomes.7 Evenwithin the selection of advanced nations considered here, the variation in such issuescan be surprisingly great.8A worthwhile endeavour1.12 Listing the difficulties with international criminal justice comparisons can in itselfseem to present a challenge to their value. But, for the most part, the analyses we havecarried out as part of this research, and the conversations we have had with experts,have rather tended to show us how much can be achieved using existing data.1.13 Even where current operational statistics do not allow for much comparison, forinstance with regard to sentencing policy, a great deal might be achieved by studyingpractice in other countries and, where it was warranted, piloting similar measures here.Likewise, though sometimes expensive, international surveys can provide valuableinsights. Just increasing the prominence of, and coverage given to, key international dataabout crime and punishment might, on its own, improve the quality of public debate oncriminal justice matters, both in this country and elsewhere.

12Part Two Comparing International Criminal Justice SystemsPart TwoInternational comparisons of key crime andjustice dataa)International trends in crime2.1 Crime levels are a key measure in any analysis of criminal justice systems. InEngland and Wales there are two main measures of crime - police recorded crimeand the British Crime Survey, which measures reports of victimisation from a nationallyrepresentative sample of the resident population of England and Wales. Each measurehas its own difficulties and benefits. As in other countries, neither can be said to becomplete. Despite this, trend data can be used to reach legitimate conclusions andmake comparisons about the direction of crime in different countries. This sectionexplores trends across all our case territories.Measuring crime levels2.2 Police recorded crime is an incomplete measure because it does not includecases where a victim does not report the crime or where police decide not to record it.Furthermore, in response to local and national priorities, police forces may be required totarget specific crimes, such as drug possession or sexual offences. While more of thesecrimes may consequently be recorded year on year, this does not necessarily mean thatmore are being committed. This targeted policing may also serve to increase numbers ofother crimes, at which resources are not specifically targeted.2.3 In some countries, as in England and Wales, police recorded crime issupplemented by national9 and international10 victimisation data on crimes experiencedby samples of individuals. International victimisation data are collected only infrequently,with the last International Crime Victimisation Survey being run in 2006.2.4 The Home Office commissioned the first British Crime Survey in 1981. The surveyhas run continuously on an annual basis since 2001, having previously been conductedroughly every two to four years. The British Crime Survey in England and Wales coversapproximately 50,000 individuals over the age of 1011 and collects information aboutlevels of, and public attitudes towards, crime in England and Wales.12

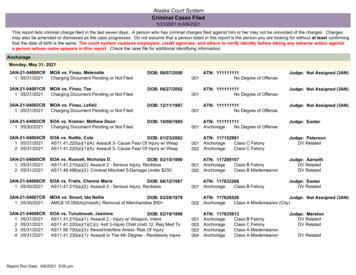

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Part Two132.5 Results are published four times a year and the survey is internationally regardedas one of the most robust and methodologically-sound currently conducted.13 It alsoproduces data more regularly than those in many other countries, for instance Canada.14It provides more complete coverage of the victimisation and crime levels experiencedby the population resident in households than police recorded crime. But, becauseit is a household victimisation survey, it does not cover crimes against public sector,commercial and other organisations, and so-called ‘victimless’ crimes such as drugpossession offences.2.6 In a small number of countries, other measures of overall crime are used in additionto police recorded crime and victimisation surveys. Thus, in Canada, police recordedcrime is adjusted before being reported according to a seriousness scale: the CrimeSeverity Index. To calculate the index, each offence on the statute book is assigneda weight, derived from average sentences handed down by criminal courts: the moreserious the average sentence, the higher the weight an offence is given, and thus thegreater its impact on the overall statistics. The Canadian government is thus able toreport on the changing severity of recorded crime as well as the change in the recordedcrime rate by population. Between 2009 and 2010, it fell by 5.6 per cent. While we arenot recommending that such an approach replace police recorded crime statisticscurrently in use in England and Wales, we think that there may be some merit in theHome Office and Ministry of Justice considering whether a measure like this mightadditionally be reported from time to time.15Trends in levels of recorded crime internationally2.7 We looked at the levels of recorded crime that had been reported internationally inrecent years. We found that, as is the case in England and Wales, there has been a cleartrend downwards since 1995.162.8 In England and Wales, there were 4.2 million crimes recorded by the police in2010‑11, down from 5.6 million in 2005-06.17 This represents a 25 per cent decrease.As over the longer period since 1995, this overall trend is confirmed by the British CrimeSurvey, though the size of the reduction reported is different. According to the BritishCrime Survey measure, 9.6 million crimes were committed against adults in 2010-11,down from 10.7 million in 2005-06, a statistically significant decrease of 10 per cent.182.9 Figure 2 overleaf presents the percentage change in the numbers of crimes overa comparable time for ten of the countries we explored, as well as California. Owing tovaried definitions of crime, and different crime recording standards, we have focused onthis percentage change, looking at the period between 2005 and 2009. Canadian data19is not included in Figure 2 because, unlike the other cases countries, it is presented asa rate per 100,000 population. For information, Canadian crime rate data also shows adecrease, of 12 per cent, between 2005 and 2009.

14Part Two Comparing International Criminal Justice SystemsFigure 2Percentage change in police recorded crime numbers, 2005 2009Percentage change in crime numbers, 2005 ia-19-20-22-25Englandand WalesScotlandNorthernIrelandRepublicof IrelandCase territories outside the United KingdomUnited Kingdom case countriesNOTES1 United States and California numbers include only violent and property crimes.2French data is on ‘crime and misdemeanours'. Data available at: http://www.justice.gouv.fr/art pix/stat annuaire p105-115 20111128.ods, accessed23/2/12.3Data does not sum due to rounding.Source: National Audit Office analysis of published crime and population data2.10 Crime in England and Wales decreased by the largest amount between2005 and 2009 (22 per cent), followed by Scotland with a decrease of 19 per cent.Three countries’ crime levels increased, with the Republic of Ireland having the largestincrease (of 12 per cent). Caution should be taken when drawing conclusions from thesetrends, as described in Part One.2.11 Further detail can be supplied for each of the constituent parts of the UnitedKingdom, because definitions of what constitutes a crime there are relatively similar.As shown above, levels of crime have been decreasing in each country at different rates,with Northern Ireland’s decreasing most slowly. But, as indicated in Figure 3, Englandand Wales still has the highest crime rate of the three administrations, while NorthernIreland’s is currently the lowest.2.12 Thus, England and Wales remains a jurisdiction with a high crime rate compared tothe other parts of the United Kingdom. This analysis appears to be true more widely too,on the basis of evidence contained in a number of standard international studies. Theseinclude studies conducted under the auspices of the European Sourcebook project,EUROSTAT and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes, all of which attempt tomake it possible to compare a large number of countries even when compatibility issuesare substantial.20

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Part Two152.13 According to the most recent European Sourcebook publication, which presentscomparable data on offences per 100,000 population for 2007, England and Wales hasa crime rate well above the mean average for 42 Council of Europe countries (Figure 4),though it is not the highest of our case countries. In 2007, the Republic of Ireland (11,407),Finland (10,368), Scotland (9,417), England and Wales (9,156), the Netherlands (7,329),Northern Ireland (6,166) and France (5,795) were all well above the mean Council ofEurope crime rate of 4,675.Figure 3Police recorded crime rates in the United Kingdom, 2010-11CountryCrime rate in 2010-111 per100,000 populationPercentage change in crimerate, 2005-06 – 2010-11England and Wales7,513-28%Scotland6,186-25%Northern Ireland5,838-18%NOTE1 Calculation: (total number of crimes/population) multiplied by 100,000.Source: National Audit Office analysis of published crime and population dataFigure 4Offences per 100,000 population (2007)Offences per 100,000 population (2007)12,00011,40710,00010,3689,4178,000Mean of f IrelandFinlandScotlandEngland Netherlandsand WalesNorthernIrelandFranceCase countries outside the United KingdomCase countries in the United KingdomSource: p. 37. European Sourcebook, 4th edition. Available at: http://europeansourcebook.org/ob285 full.pdf

16Part Two Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems2.14 The reasons why England and Wales should have a high crime rate, but one whichis falling at a fast rate, are undoubtedly complex. This complexity itself can be difficult forpoliticians and experts to communicate to the public at large. Media organisations andpoliticians often tend to focus on one of the two facts to the exclusion of the other. Inreality, the crime rate in England and Wales may be high because the incidence of crimeis genuinely greater than elsewhere, or it may be because of some of the measurementand categorisation differences described in Part One, or because the police arerecording crime more effectively. Ironically, given the sustained doubts in some quartersabout whether crime is genuinely falling, it is this trend that is the more verifiable of thetwo, as it is backed up by two reputable sources.21Homicide2.15 Those wanting to understand high-level variations in violent crime internationally oftenturn to homicide rates as the most accurate guide. This is because the basic definition ofhomicide is clear (although even here there can be measurement differences to control forbetween countries), and because it is generally taken that, even in less advanced nations,a great proportion of homicides are likely to come to the attention of the authorities.2.16 In the UK, homicide is typically the crime of greatest interest to the media, forunderstandable

Comparing International Criminal Justice Systems Part One 9 Benefits of international comparisons 1.3 International comparisons have an important role to play in building understanding of how individual criminal justice systems are functioning. They can also help to improve them. Each jurisdiction has a single criminal justice system, which means