Transcription

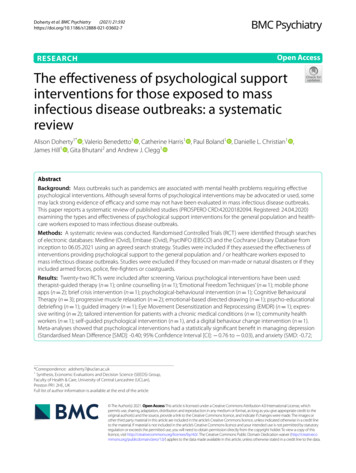

(2021) 21:592Doherty et al. BMC -7Open AccessRESEARCHThe effectiveness of psychological supportinterventions for those exposed to massinfectious disease outbreaks: a systematicreviewAlison Doherty1* , Valerio Benedetto1 , Catherine Harris1 , Paul Boland1 , Danielle L. Christian1 ,James Hill1 , Gita Bhutani2 and Andrew J. Clegg1AbstractBackground: Mass outbreaks such as pandemics are associated with mental health problems requiring effectivepsychological interventions. Although several forms of psychological interventions may be advocated or used, somemay lack strong evidence of efficacy and some may not have been evaluated in mass infectious disease outbreaks.This paper reports a systematic review of published studies (PROSPERO CRD:42020182094. Registered: 24.04.2020)examining the types and effectiveness of psychological support interventions for the general population and healthcare workers exposed to mass infectious disease outbreaks.Methods: A systematic review was conducted. Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) were identified through searchesof electronic databases: Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (EBSCO) and the Cochrane Library Database frominception to 06.05.2021 using an agreed search strategy. Studies were included if they assessed the effectiveness ofinterventions providing psychological support to the general population and / or healthcare workers exposed tomass infectious disease outbreaks. Studies were excluded if they focused on man-made or natural disasters or if theyincluded armed forces, police, fire-fighters or coastguards.Results: Twenty-two RCTs were included after screening. Various psychological interventions have been used:therapist-guided therapy (n 1); online counselling (n 1); ‘Emotional Freedom Techniques’ (n 1); mobile phoneapps (n 2); brief crisis intervention (n 1); psychological-behavioural intervention (n 1); Cognitive BehaviouralTherapy (n 3); progressive muscle relaxation (n 2); emotional-based directed drawing (n 1); psycho-educationaldebriefing (n 1); guided imagery (n 1); Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) (n 1); expressive writing (n 2); tailored intervention for patients with a chronic medical conditions (n 1); community healthworkers (n 1); self-guided psychological intervention (n 1), and a digital behaviour change intervention (n 1).Meta-analyses showed that psychological interventions had a statistically significant benefit in managing depression(Standardised Mean Difference [SMD]: -0.40; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.76 to 0.03), and anxiety (SMD: -0.72;*Correspondence: adoherty7@uclan.ac.uk1Synthesis, Economic Evaluations and Decision Science (SEEDS) Group,Faculty of Health & Care, University of Central Lancashire (UCLan),Preston PR1 2HE, UKFull list of author information is available at the end of the article The Author(s) 2021. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, whichpermits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to theoriginal author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images orother third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit lineto the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutoryregulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of thislicence, visit http:// creat iveco mmons. org/ licen ses/ by/4. 0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http:// creat iveco mmons. org/ publi cdoma in/ zero/1. 0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Doherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 2 of 2895% CI: 1.03 to 0.40). The effect on stress was equivocal (SMD: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.51). The heterogeneity ofstudies, studies’ high risk of bias, and the lack of available evidence means uncertainty remains.Conclusions: Further RCTs and intervention studies involving representative study populations are needed to informthe development of targeted and tailored psychological interventions for those exposed to mass infectious diseaseoutbreaks.Keywords: Review, Pandemics, Public health, Mental health, Interventions, Mass outbreaksBackgroundOver a decade before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, healthcare organisations across the worldwere preparing for an influenza pandemic of unpredictable scale and impact [1–5], involving increased rates ofmorbidity and mortality among the general population,high healthcare demands, and considerable psychologicalstress amongst healthcare workers [1, 2, 4]. It is evidentthat the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are pervasiveaffecting the mental health of many of those exposed [6,7], including healthcare workers [8–11].The effects on healthcare workers is a concern, giventheir importance in preventing and managing the consequences of pandemics [12, 13]. A mass outbreak putshealthcare workers in unprecedented situations including dilemmas over how to balance their own physicaland mental healthcare needs along with those of theirpatients [13]. Experience with the SARS outbreak in2003 highlighted how the acute stress of an outbreak canimpact on the mental health and wellbeing of healthcareworkers and how this, in turn, can affect their abilityto care for patients [14, 15]. During the SARS outbreakmany healthcare workers reduced their working hoursand face-to-face involvement with patients [14, 15]. Twoyears after the mass infectious disease outbreak, healthcare practitioners that had treated SARS patients hadelevated signs of chronic stress compared to healthcarepractitioners not treating SARS patients [15]. SARSCoV-2 is a virus that can cause COVID-19, a mass infectious disease. Reducing the mental health impact of thoseexposed to such mass infectious disease outbreaks is fundamental to the continued provision of health and socialcare [2, 5]. However, the planning and delivery of suchpsychological support may differ within and betweencountries [16–18].Although several forms of psychological interventions[19] may be advocated or used, some are recognised asbeing harmful, others lack strong evidence of efficacyand some have not been evaluated in mass infectious disease outbreaks [16, 19–22]. Importantly, specific population groups such as children and young people, ethnicminorities, and people on low incomes, may be morevulnerable to mental health problems associated withmass infectious disease outbreaks and require targetedinterventions [23–28]. Such uncertainties call for thedevelopment and implementation of effective targetedinterventions for all those exposed to mass infectiousdisease outbreaks [11, 16, 26]. Despite several systematicreviews assessing interventions to manage psychologicalproblems associated with different types of mass outbreaks [28–31], doubts remain due to certain shortcomings. Some focus on different types of disasters (not justepidemics or pandemics), on interventions for childrenonly, for healthcare workers only, and/or exclude recentevidence [28–31]. Consequently, we conducted a systematic review to identify the types of psychological interventions used in previous mass infectious disease outbreaks(similar to COVID-19) and during the COVID-19 pandemic to support the general population and healthcareworkers, and how effective these interventions have been.Findings are expected to provide evidence-based information to inform research, policy and practice.MethodsSearch strategyOur systematic review was conducted according to a pre-registered protocol (PROSPERO 2020CRD:42020182094. Registered: 24.04.2020), followingestablished PRISMA guidance and reporting standards [32, 33]. We identified studies through searches ofelectronic databases, including Medline (Ovid), Embase(Ovid), PsycINFO (EBSCO) and the Cochrane LibraryDatabase, using a predetermined search strategy and prepiloted screening tool (Additional files 1 & 2). Databaseswere searched from inception to 06.05.2021.Study selectionInclusionWe included Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs)including Cluster RCTs and Parallel RCTs that assessedthe comparative effectiveness of interventions providingpsychological support to the general population (all ages)and/or healthcare workers (e.g. nurses, doctors) exposedto mass infectious disease outbreaks including COVID19, H1N1, swine flu, SARS, Ebola, and MERS. Psychological support could include interventions such as cognitivebehavioural, psycho-social or psycho-educational interventions. Any comparator was included, for example:

InterventionPsychological or psychosocial interventions used to support the mentalhealth of those exposed to massinfectious disease outbreaks, including:H1N1 (a type of influenza A virus),swine flu, Severe Acute RespiratorySyndrome (SARS - SARS-CoV-2 is a virusthat can cause COVID-19, a disease),Ebola, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and COVID-19.PopulationHealthcare staff exposed to massinfectious disease outbreaks e.g.nurses, physicians, allied health professionals, healthcare support staff.General population, (all ages) including children, adolescents, adults,patients exposed to mass infectiousdisease outbreaks.Any healthcare setting or any community setting, in any country.Table 1 Eligibility criteriaAny comparator. For example, comparison with no care, with usual care,with another type of psychologicalsupport intervention, or with a pharmacological intervention.ComparatorMeasurable changes (or perceivedlevels of changes) in mental healthdisorders including depression, anxiety or stress.OutcomesRandomised Controlled Trials (RCTs).Cluster RCTs.Study DesignDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 3 of 28

Doherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592comparison with no intervention, with usual care, comparisons between a psychological intervention andanother type of psychological intervention(s), or pharmacological intervention(s). Effectiveness was assessedusing any measure of changes in psychological or mentalhealth impact: specifically reduced depression, anxietyor stress levels measured by a recognised outcome measurement tool such as the Patient Health Questionnairedepression scale (PHQ-9) or the Generalized AnxietyDisorder scale (GAD-7) or the Depression, Anxiety andStress Scale (DASS-21). Relevant systematic reviews wereonly used to identify any RCTs that may not have alreadybeen identified by the review’s initial electronic searches.ExclusionNon-RCT studies were excluded. Studies were excludedif they involved armed forces, police, firefighters, coastguards; terrorism / war; or, man-made or natural disasters (e.g. tsunamis). Abstracts, editorials, commentaries,or opinion pieces were excluded, as were studies wherethe full text was not available or if they were not published in English. Table 1 summarises the eligibility criteria for the review. Titles and abstracts of papers fromthe searches were screened independently by pairs ofreviewers (AJD/VB/CH/AJC), using an eligibility criteriascreening tool (Additional file 2). Full-text manuscriptsof studies that met the criteria at the title and abstractscreening stage were retrieved and screened independently by the pairs of reviewers (AJD/VB/CH/AJC) usingthe same criteria.Data extraction and quality assessmentThe pairs of two reviewers (AJD/VB/CH/AJC) independently extracted each study’s data using a pre-piloteddata extraction form, checking each other’s extraction.Data were extracted into the following categories: study(first author, year); country; setting; study aims; mass outbreak (type); participant characteristics; intervention(s);comparator(s); and outcomes. The pairs of reviewersindependently assessed the quality of included studiesusing the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoBv2) Tool [34] andchecked one another’s assessments. Any discrepanciesat any stage were resolved through discussions to reachmutual consensus.Data analysisStudies were synthesised narratively with tabulation ofresults. Where studies presented continuous outcomemeasures of depression, anxiety and stress, they werepooled through meta-analysis presenting results as pointestimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Althoughoutcomes were measured on different scales, they werebased on the same underlying construct, allowingPage 4 of 28standardised weighted mean differences (SMDs) to beestimated. Given the variation in the studies, randomeffects models were used to pool outcomes. Heterogeneity was assessed through visual inspection of forest plotsand the calculation of the I2 statistics. Pre-planned subgroup analyses explored the influence of study setting,participants and risk of bias. Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager version 5.4.1 (CochraneCollaboration 2020).ResultsA combined total of 12,104 citations were identified fromthe database searches after removal of duplicates. Nofurther eligible RCTs were identified from other sources(reference checks of relevant reviews). Twenty-twopapers met the eligibility criteria and reported information for quality appraisal and data extraction [35–56].Fig. 1 summarises the study selection process. Table 2provides a summary of the included studies.Quality assessmentMost of the included studies were assessed as beingof high risk of bias (n 12/22), or of ‘some concern’(n 8/22). Two studies were assessed as being of lowrisk of bias [54, 55]. Studies that were considered as highrisk or of ‘some concern’ showed shortcomings due toeither their randomisation process, deviations from theirintended interventions, missing outcome data, theirmeasurement of outcomes, or selective reporting. Table 3provides an overall summary of the individual risk of biasassessments for each of the included studies.Year and location of studiesMost of the studies included in the review were published in 2020 or 2021 (n 21). One study was published in 2006 [46]. Studies were conducted in severaldifferent countries: Belgium (n 1) [53], Canada (n 1)[45], China (n 6) [40–44, 56], Hong Kong (n 1) [46],Iran (n 3) [39, 48, 51], Italy (n 3) [36, 49, 50], Oman(n 1) [35], Serbia (n 1) [54], Spain (n 1) [38], Sweden (n 1) [55], and Turkey (n 2) [37, 47]. One study[52] involved participants from seven different countries(Australia, Canada, France, Mexico, Spain, UK and USA).Nine of these studies’ countries were high-income countries (HICs) [35, 36, 38, 45, 46, 49, 50, 53, 55] and 12 wereupper-middle-income countries (UMICs) [37, 39–44,47, 48, 51, 54, 56]. One study was conducted in countries from both HIC and UMIC [52]. No published studies were identified from either in low-income-countries(LICs) or lower-middle-income countries (LMICs).

Doherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 5 of 28Fig. 1 PRISMA FlowchartParticipant characteristicsPatientsEleven studies involved participants who were patients,of which: seven involved patients with COVID-19 [39,40, 42–44, 47, 48]; three with pre-existing chronic diseases exposed to COVID-19 and / or with a diagnosis of COVID-19 [41, 52, 53]; and one involved adultpatients with chronic diseases exposed to SARS [46].General populationSeven studies involved participants from general populations exposed to COVID-19 [35, 36, 45, 51, 54–56].Two of these seven studies involved schoolchildren [45,56] and one involved college students [51].

Country; settingOman; Community.Italy; Community.First author, year,(Study type)Al-Alawi, 2021(RCT) [35]Carbone, 2021(RCT) [36]Table 2 Summary of included studiesAdults in the general populationliving in Italy during the COVID19 pandemic (N 54) (n 26intervention group; n 28control group): 77% female(N 41); mean age: 34.34 years(SD: 8.27 years).Adults in the general populationliving in Oman during COVID-19pandemic (N 60) but dataonly available for N 46 (n 22intervention group; n 24control group); of which: 78%female; mean age 28.51 years(Standard Deviation (SD):8.70 years).PopulationOnline counselling sessionfocusing on reducing clinicalsymptoms and increasing wellbeing during the first COVID-19Italian lockdown. One session(only) lasting 60 min.Follow-up: none.Internet-based (email-delivered)therapist-guided online therapyfocusing on symptoms of anxiety and depression. One sessionper week for 6 weeks.Follow-up: 6 weeks.Intervention and follow-upControl group were on a waiting list.Control group received anautomatic weekly newslettervia email containing self-helpinformation and tips to copewith psychological distressassociated with COVID-19.ComparatorOutcome measures used:Self-report questionnaires: BSIInventory; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS);State-Trait Inventory of Cognitiveand Somatic Anxiety (STICSA);The Warwick-Edinburgh MentalWellbeing Scale (WEMWBS)Compared to the control group,the intervention group showeda significant reduction inanxiety (M SD 36.65 8.35 vs48.04 11.51; p 0.001).Outcome measures used:Patient Health Questionnaire-9(PHQ-9) and General AnxietyDisorder-7 (GAD-7) scale.Analysis of covariance indicateda significant reduction in theGAD-7 scores (F1,43 7.307;P .01) between the two groupsafter adjusting for baseline scores.GAD-7 scores of participantsin the intervention group wereconsiderably more reducedthan those of participants inthe control group (β 3.27;P .01). A greater reduction inmean PHQ-9 scores was observedamong participants in theintervention group (F1,43 8.298;P .006) than those in the controlgroup (β 4.311; P .006).Although the levels of anxietyand depression reduced in bothstudy groups, the reduction washigher in the intervention group(P .049) than in the controlgroup (P .02).OutcomeDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 6 of 28

Spain; Hospital and community. Healthcare workers (N 482)(n 248 intervention group;n 234 control group): 83.2%female; median age: 42 years;33.4% nurses; 31.7% physicians;30.5% nurse assistants;81.3% worked in a hospital setting; 12.7% worked in primarycare; 6% worked in home-caresettings.Fiol-DeRoque, 2021(Parallel RCT) [38]Hospital-based nurses (N 72completed the intervention)(n 35 intervention group;n 37 control group):88.8% female; mean age:33.45 years (SD: 9.63 years).Turkey; Hospital.Dincer, 2021(RCT) [37]PopulationCountry; settingFirst author, year,(Study type)Table 2 (continued)ComparatorA psychoeducational, mindfulness-based mHealth intervention entitled PsyCovidApp.Two-week duration.Follow-up: by telephonebetween 24 h and 10 days postintervention using the samequestionnaire used at baseline.Control app comprising briefwritten information about themental healthcare of healthcareworkers during the COVID-19pandemic (adapted from a set ofmaterials developed by the Spanish Society of Psychiatry).Brief online form of EmotionalControl group received noFreedom Techniques (EFT)intervention.aimed at prevention of stressand anxiety in nurses involvedin treatment of COVID-19patients. One session (only) lasting 20 min.Follow-up: none.Intervention and follow-upOutcome measures used: Acomposite of depression, anxiety,and stress: Depression Anxietyand Stress Scale (DASS21). The Intervention Group presented significantly lower overallscores (suggesting improvedmental health) at 2 weeks thanthe Control Group (adjustedstandardized mean difference 0.29; 95% CI: 0.48 to 0.09; p 0.004). The Intervention significantlyimproved symptoms of: Anxiety (adjusted standardisedmean differences) ( 0.26; 95%CI-0.45 to 0.08; p .004); Stress (adjusted standardisedmean differences)( 0.30; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.09;p .003); PTSD (adjusted standardisedmean differences)( 0.20; 95% CI-0.37 to 0.03;p 0.01) No significant differenceswere observed for symptoms ofdepression.Outcome measures used:Subjective Units of Distress (SUD)scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-1), burnout scale viaonline survey The mean anxiety score reduction on the post-test for theintervention group was highlysignificant (p 0.001). The mean post-test anxietyscore for the control group wasnot statistically significantly different.OutcomeDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 7 of 28

Country; settingIran; HospitalChina; Hospital.First author, year,(Study type)Gharaati Sotoudeh, 2020(RCT) [39]Kong, 2020(RCT) [40]Table 2 (continued)Patients with COVID-19(N 144) (n 13 interventiongroup; n 13 control group):51.4% female; 51.4% aged over50 years.Patients with diagnosis ofCOVID-19 (N 30) (n 16intervention group; n 14 control group): 53.3% female; agerange: 20 to 70 years; mean ageIntervention Group: 41.92 years(SD: 12.2 years); mean ageControl Group: 44.7 years (SD:14.2 alUsual care.Intervention which includedbreathing exercises and psychosocial support.Duration: 10 days.Breathing exercises performeddaily for 20 mins in the morning.Psychosocial support lastedapprox. 15 mins.Delivered by two trained medical staff.Follow-up: after 10 days treatment.Brief Crisis Intervention Package. Routine care.Duration: four 60-min sessionsfor 1 month.Weekly sessions comprised: (1)greetings and introduction tothe package; (2) adjustmentsskills; (3) responsibility andfactualism; (4) spirituality.Follow-up: 1 month.Intervention and follow-upOutcome measures used:Hospital Anxiety and DepressionScales for Anxiety and Depression(HADS-A and HADS-D); PerceivedSocial Support Scale (PSSS) selfreport.After a 10-day intervention, theHospital Anxiety and DepressionScale-Anxiety (HADS-A) score(Mean 6.15 / 3.579) and theHospital Anxiety and DepressionScale-Depression (HADS-D) score(5.92 / 3.730) were significantly reduced in the Intervention Group (both p 0.001).Outcome measures used:DASS21, symptom checklist (SCL25), Quality of Life Assessmentdeveloped by the World HealthOrganisation (WHO-QOL) The t-test results showed thatthe average score of depression, anxiety and stress after theintervention was statisticallysignificant compared to the pretest (p 0.05). The results of the ANCOVAshowed statistically significantdifferences as a result of theintervention vs usual care indepression, anxiety, stress,mental health, and quality of life(p 0.05).OutcomeDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 8 of 28

Country; settingChina; Hospital.First author, year,(Study type)Li, 2020(RCT) [41]Table 2 (continued)Patients with COVID-19 diagnosis (N 93) (n 47 interventiongroup; n 46 control group):64.5% female; mean age:48 years; 20.4% had chronicdiseases.PopulationComparatorCognitive Behavioural TherapyRoutine care.(CBT).Comprised: cognitive intervention, relaxation techniques training, problem-solving training,and social support strategy.Performed once a day in themorning, taking 30 mins tocomplete. Recorded by nurses.Delivered face-to-face andadjusted to suit individualpatient’s needs.Follow-up: not reported.Intervention and follow-upOutcome measure used:Chinese version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale(DASS-21) A significant decrease in themeans for scales of depression, anxiety and total DASS-21(DASS-12 is the Chinese versionof the Depression Anxiety andStress Scale-21) were found inboth intervention (p 0.001)and control groups (p 0.001).Participants in the InterventionGroup had a bigger reduction onmeans for scales of depressionand anxiety. After the intervention, moreparticipants in the InterventionGroup had no depression or anxiety symptoms than in the ControlGroup, but no statistical differences were found (p 0.05). Compared with participantswith chronic disease, participantswith no chronic disease had astatistically significantly largerreduction of total DASS-21 scale(mean difference on the DASS-21scale 4.74, 95% CI: 9.31 to 0.17; p 0.04). The length of hospital stay wasstatistically significantly associated with a greater increase inanxiety in the Intervention Group(p 0.005), whilst no statisticallysignificant association was foundin the Control Group (p 0.29).OutcomeDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 9 of 28

Country; settingChina; Hospital.China; Hospital.First author, year,(Study type)Liu, 2020(RCT) [42]Liu, 2021(a)(RCT) [43]Table 2 (continued)Patients with COVID-19 hospitalised infections (N 140) (n 70intervention group; n 70control group); (59% female;54% aged 36 years and over.Patients with confirmed COVID19 (N 51) (n 25 interventiongroup; n 26 control group):56% male; mean age 50.41 years(SD: 13.04 years).PopulationComparator‘WeChat’ intervention group.Promoted during ward roundsand through daily broadcasts.Included daily broadcastswhich provided knowledgeabout COVID-19 – includingprevention, treatment, andrecovery measures. Participantsencouraged, through a WeChatapp platform, to conduct selfintroductions, make friends,share experiences, help eachother build confidence, satisfyspiritual issues, and soothestress.Follow-up: none.Routine care.Progressive muscle relaxation.Routine care.Performed for between20–30 min per day over a periodof five consecutive days.Follow-up: none.Intervention and follow-upOutcome measures used: StateAnxiety Inventory (SAI). Results showed that the average State Anxiety Inventory(SAI) score of the trial groupwas 38.5 13.2, and it was15.9% lower than the controlgroup (45.8 10.4) resulting in astatistically significant difference(p 0.001). Females, young, well-educated,and those without underlyingdiseases were more willing toinvolved in, and more vigorousto fulfil intervention activities andrehabilitation exercises; moreover,they found it easier to understandCOVID-19 prevention methodsand countermeasures.Outcome measures used: StateTrait Anxiety Scale (STAI). The t-test results showed thatthe average score of anxietybefore intervention was notstatistically significant [betweenthe two groups] (p 0.713), andthe average score of anxiety afterthe intervention was statistically significant (Interventiongroup: Mean 44.96 / (SD)12.68;Control group: Mean 57.15 / (SD)9.24; p 0.001).OutcomeDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 10 of 28

Country; settingChina; Hospital.Canada; Schools.First author, year,(Study type)Liu, 2021(b)(RCT) [44]Malboeuf-Hurtubise, 2021(Cluster RCT) [45]Table 2 (continued)Schoolchildren (N 22): (n 14intervention group; n 8control group): mean age:11.3 years; 50% female.Patients with COVID-19 fromfive sites (N 273) (n 137intervention group; n 136control group): 59% male;mean age intervention group:43.76 years (SD: 14.31 years);mean age control group:41.52 years (SD: 11.51 years).PopulationComparatorEmotion-based directedMandala drawing intervention.drawing intervention. TheGroup-based, delivered onlineintervention was group-based, and remotely.delivered online and remotely.Duration: 5 weeks (1 sessionper week with each sessionlasting approximately 45 mins).Content involved: story of avirus (Comic strip); drawing howyou feel; drawing viruses withfunny names; drawing whatyou are afraid of and putting itin a bottle and throwing this inthe bin; drawing what makesyou anxious and where you feelit in your body; drawing yourCOVID-19 cure; and forecastinghow your heart feels.Follow-up: none reported.Computerised Cognitive Behav- Treatment as usual.ioural Therapy (cCBT)A self-help interventiondelivered through 10 min ofself-directed individual therapyper day for 1 week at each trialcentre. The cCBT interventionwas installed on an iPad onlyavailable to research therapists.Therapists first show participants how to use the systembefore the participants can usethe self-help intervention.Follow-up: one-month postintervention.Intervention and follow-upOutcome measure used:Behaviour Assessment Scale forChildren-3rd edition (BASC 111) No statistically significant impacton levels of anxiety or depression in either the intervention orcontrol group as measured byANCOVA (p 0.26 for anxiety;p 0.68 for depression). For anxiety: Interventiongroup had means (SD) pre-test:3.71(1.48) and post-test: 3.5(1.70);Control group had means (SD)pre-test: 3.25(2.05) and post-test:2.87(0.83). For depression Interventiongroup had means (SD) pretest: 2.46(1.71) and post-test:2.07(1.49); Control group hadmeans (SD) pre-test: 2.62(1.84)and post-test: 2.62(1.50).Outcome measures used: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17(HAMD); Hamilton Anxiety Scale(HAMA), Self-Rating DepressionScale, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.A mixed-effects repeated measures model revealed statisticallysignificant improvement indepression (p 0.001), anxiety(p 0.001), during the post-intervention and follow-up periods inthe intervention group comparedto the control group.OutcomeDoherty et al. BMC Psychiatry(2021) 21:592Page 11 of 28

Country; settingHong Kong; Community.First author, year,(Study type)Ng, 2006(RCT) [46]Table 2 (continued)Community RehabilitationNetwork for participants withchronic disease (N 51) (n 25intervention group; n 26 control group): 74.5% female; meanage of intervention group:53.9 years.PopulationStrength-Focusedand Meaning-OrientedApproach for Resilience andTransformation (SMART)debriefing intervention forpeople exposed to SARS.One-day psycho-educationalintervention.Follow-up: one-month postintervention.Intervention and follow-upNo interventionComparatorOutcome measure used: BriefSymptom Inventory (BSI)Paired t-tests were conductedfor changes between baseline ( T0) and immediately at the endof the session ( T1) only for theintervention group: The Depression score droppedsignificantly (p 0.01). The Anxiety, Somatization andHostility scores did not.Repeated-measure ANOVAwas conducted for changes

psychological support to the general population (all ages) and/or healthcare workers (e.g. nurses, doctors) exposed to mass infectious disease outbreaks including COVID-19, H1N1, swine u, SARS, Ebola, and MERS. Psycholog - ical support could include interventions such as cognitive behavioural, psycho-social or psycho-educational inter-ventions.