Transcription

2020Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, Bijzondere Collecties, 1019 E 29: 12020Den Haag 1629, p. 111-112.De Zeventiende EeuwUit: Proteus ofte minne-beelden verandert in sinne-beelden door I. Cats,De Zeventiende Eeuw2020Vermijt u, domme jeught, ajuyn te willen schellen,Of, siet, uw treurigh oogh sal van de tranen swellen;Maer sooje met de vrucht wilt spelen sonder leet,Soo raecktse sachtjens aen, en laet het ding gekleet.Ghy meught u, jongh gesel, ter eeren wel vermaken,Maer pleeght geen ander min als door eerbiedigh raken.’t Is noch al, soo het plagh: Acteon naeckt verdriet,Indien hy sonder kleet de jonge nymphen siet.JAARBOEKJAARBOEKJAARBOEK 20202020De Zeventiende EeuwJAARBOEKJAARBOEKNuda movet lachrimasKomt dit gewas ontkleet,Al was ’et lief, soo wort ’et leet.cultuur in de nederlandenin interdisciplinair perspectief9 789087 0487859789087048785.pcovr.JB DZE2020.indd Alle pagina's08-09-20 14:05

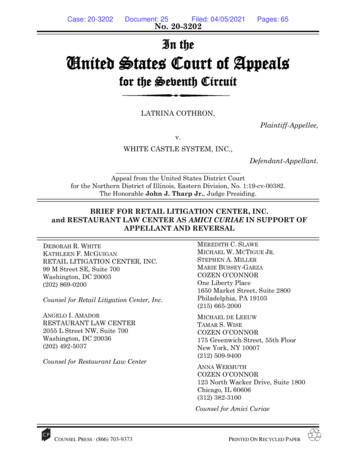

Kendra GrimmettRubens’s painting of the drunk demigod Hercules was a relatable, even sympathetic, figure for men living in seventeenth-century Antwerp. Rather than scorn or harsh judgment, the author argues that TheDrunken Hercules prompted laughter, and personal memories of drinking misadventures, from maleaudiences.A muscular male nude totters on unsteady legs in the center of Peter Paul Rubens’s twometer-tall Drunken Hercules (fig. 1). Ironically, the legendary strongman cannot support theweight of his own burly body. Despite his barrel chest, thick neck, and powerful limbs, Hercules comically requires the support of a satyr and satyress to keep him upright. Moreover, ifthe satyr were not supporting the bottom of Hercules’s wine jug, the inebriated musclemanwould drop his half-empty pitcher. The formidable hands that strangled the Nemean lionappear limp and useless here. Excessive drinking has cost the hero his strength and other attributes. The satyr on the far right – who sticks out his tongue – wears Hercules’s lion-skinpelt. Below, a putto drags the hero’s enormous club, now rendered harmless. The dancingbacchante on the left, who looks out at the viewer and points at the bleary-eyed drunkard,encourages audiences to laugh at Hercules’s foolish intemperance.Drunken Hercules may have attended a bacchanal – a hedonistic drinking celebration inhonor of Bacchus, the god of wine. Hercules’s companions – satyrs, a bacchante, and a putto – are typical bacchanalian revelers. Moreover, the ground is littered with objects associated with the wine god: an overturned basket of grapes, flutes, and a tambourine. Peekingthrough Hercules’s legs, a leopard – an animal that pulled Bacchus’s chariot after the god’s*Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdStumbling along the VirtuousPath with Rubens’s DrunkenHercules* I would like to thank my advisors Larry Silver and Shira Brisman for their endless support and invaluable sugges-tions. My gratitude also goes to the editorial board of this publication for their constructive comments that enrichedthis paper. And I am indebted to Bert Schepers, Brecht Vanoppen, Bert Watteeuw, Suzanne Duff, Petra Maclot, andall of my colleagues at the Rubenianum for their generous assistance and thoughtful conversations. This article isdedicated to my mother Kelly Grimmett, whose edits and insights always improve my work.419789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4107-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmettFig. 1 Peter Paul Rubens, TheDrunken Hercules, c. 1613-1615,oil on panel, 220 x 200 cm.Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister,Staatliche KunstsammlungenDresden, Photo Credit: Estel /Klut. Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdreturn from India – bites the dangling pelt.1 The god himself is not pictured, but all the Bacchic attributes and Hercules’s intoxication imply his presence.Hercules’s fondness for drinking was well represented in classical texts and images.2 Under the influence of alcohol, the misguided hero harassed priestesses, wrecked dinner parties, stole Apollo’s Delphic tripod, and even killed people.3 With hubris equal to his stature,Hercules unwisely challenged Bacchus to a drinking contest. Drunken Hercules may depictthe hero’s defeat. Natale Conti’s Mythologiae (1567), a standard source for classical mythologyin the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, includes an ancient Greek epigram describingHercules after a bout of drinking:1See the two leopards pulling Bacchus’s chariot in Titian’s painting Bacchus and Ariadne (c. 1520-1523) at theNational Gallery in London. In Rubens’s Dreaming Silenus (c. 1610-1612) at the Gemäldegalerie der Akademie derbildenden Künste in Vienna, a spotted feline appears under the arm of Bacchus’s slumbering drinking companion.2On the drunken Hercules motif, see E. McGrath, ‘The painted decoration of Rubens’s house’, in: Journal of theWarburg and Courtauld Institutes 41 (1978), 263-268.3McGrath, ‘Rubens’s house’, 264.429789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4207-09-20 11:37

Stumbling along the Virtuous Path with Rubens’s Drunken HerculesThis subduer of all, of whom, telling of his twelve labours, men sing because of his mighty valour, nowafter the feast is heavy with wine, and rolls along unsteady in his gait from drink, conquered by softBacchus, the loosener of the limbs.4The demigod who slew countless monsters was vulnerable to the allure and effects of alcohol. Together, the myths recounted in Conti’s Mythologiae present an ambivalent imageof Hercules: his epic triumphs are matched by his struggles with wine, women, and rage.5Despite his many dishonorable exploits, Hercules was a popular and celebrated figure inthe early modern period, appearing in books, paintings, prints, and on household objects.To understand the problematic hero’s appeal to educated men, especially the Flemish artistPeter Paul Rubens, this paper examines contemporary discourses on Hercules, virtue, anddrinking in the Low Countries. For Rubens and his peers, Hercules represented the complex relationship between virtue and vice. After close visual analysis and consideration of thehistorical context of the painting, I conclude that The Drunken Hercules was a relatable, evensympathetic, figure for men living in seventeenth-century Antwerp. The fallible demigodembodied every man’s struggle to behave virtuously.Themadossier Deugd en ondeugd Hercules at the Crossroads Rubens painted The Drunken Hercules and its pendant, The Coronation of a Hero, around1613 to 1615 (fig. 2).6 No documentation regarding the paintings’ intended audience survives.7However, the paintings were still in Rubens’s possession when he died in 1640, so it is possible that he designed the pair for his personal art collection.8 Based on the composition ofthe images, The Drunken Hercules hung on the left, facing his sober counterpart on the right.4 Natale Conti’s Mythologiae, translation J. Mulryan and S. Brown, Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies,vol. 316, Tempe 2006, 594.5On the ambivalence of Hercules, see P. Simons, ‘Hercules in Italian Renaissance art. Masculine labour andhomoerotic libido’, in Art History 31.5 (2008), 632-664.6The Drunken Hercules and The Coronation of a Hero are accepted as pendants based on their identical dimensionsand format, complementary compositions, related subject matter, and sequential descriptions in the inventory ofworks for sale from Rubens’s estate. Workshop copies of the pendants went to Mantua. N. Büttner, Allegories andsubjects from literature, 2 vols., Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard 12, 1, London, Turnhout 2018, 138-152.7L. Rosenthal, Gender, politics, and allegory in the art of Rubens, New York 2005, 64.8Rosenthal, Gender, politics, and allegory, 64; J. Muller, ‘Rubens’s collection in history’, in: K.L. Belkin and F. Healy(eds.), A house of art. Rubens as collector, Antwerp 2004, 54. The Drunken Hercules was not the only inebriated figurethat remained in Rubens’s art collection until 1640. Munich’s Drunken Silenus (1616-1617) hung in a small hall in theartist’s house. For more on Silenus, see L. Davis, ‘“On feet made unsteady by age and wine.” Rubens’ Silenus andHuman Aging’, in: C. van Wyhe (ed.), Rubens and the human body, Turnhout 2018, 249-268. The 1640 inventory alsoincludes Rubens’s corpulent Bacchus (c. 1638-1640) at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. For more onBacchus, see L. Davis, ‘A Gift from Nature. Rubens’ “Bacchus” and Artistic Creativity’, in Nederlands KunsthistorischJaarboek 55 (2004), 226-243.439789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4307-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmettFig. 2 Peter Paul Rubens, The Cor-onation of a Hero, c. 1613-1615, oilon panel, 221.5 x 200.5 cm.Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich,Photo Credit: Erich Lessing / ArtResource, NY. Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdThe Coronation of a Hero depicts Victory, a winged female nude, crowning an armored manwith a laurel wreath. That man earned his leafy accolade by resisting worldly temptations: heplaces his foot on the back of Drunkenness or Intemperance, personified by an ivy-wreathedsatyr. He turns away from the seated embodiment of Lust, a nude Venus joined by Cupid.Lurking in the shadows, a snake-haired woman eyes the victorious soldier. This frightful female, whom the man ignores, represents Discord or Envy.9 The armored hero thus forgoesthe very pleasures in which Hercules indulges.The 1640 inventory of Rubens’s estate refers to The Coronation of a Hero as item 156, ‘Apeice uppon bord called the Christian Knight.’ Item 157 is its pendant, ‘A drunken Hercules uppon bord.’10 The Christian Knight, or miles christianus, is a theological concept that9Büttner, Allegories, 150.10 Büttner, Allegories, 141. In the French translation of the inventory, or ‘Specification’, the paintings are describedas: ‘Vn cheualier Chrestien couronné de la victoire sur fond de bois’ and ‘Vn Hercule enyuré sur fond de bois’.449789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4407-09-20 11:37

Stumbling along the Virtuous Path with Rubens’s Drunken Herculescharacterizes Christians as warriors inthe struggle against forces of evil.11 InNetherlandish prints from the sixteenthand seventeenth centuries, the ChristianKnight is traditionally confronted by Sin,Death, and the Devil, with some depictions including Lady World and Lust. UllaKrempel suggests that Rubens adoptedelements of the Christian Knight in hisCoronation of a Hero, but the armored figure is not a true Christian Knight becausehe battles different enemies.12 Instead,the virtuous hero’s adversaries – Drunkenness, Lust, and Discord – are closely associated with Hercules. The strongman cannot resist alcohol or women, andthe evil personification that he most commonly defeats in Rubens’s oeuvre is Discord (fig. 3). By depicting The Coronationof a Hero confronting Hercules’s temptations, Rubens indicates that the hero mayalso be interpreted as Hercules.Because The Drunken Hercules depicts the consequences of Vice and TheCoronation of the Hero celebrates Virtue,scholars interpret the pendants as alternate endings to the ancient Crossroadsallegory that originated in Prodicus’s Horai (fifth century BCE) and appeared inXenophon’s Memorabilia (fourth centuryBCE).13 Hadrianus Junius’s Emblemata,published in Antwerp in 1565, illustratesFig. 3 Christoffel Jegher, after Peter Paul Rubens, Herculesovercomes Discord (Envy), c. 1635, woodcut, 61.2 x 37.1 cm.Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, object number RP-P-OB-39.797.Themadossier Deugd en ondeugd 11 On the Christian Knight motif, see U. Krempel, ‘Bemerkungen zur Ikonographie der “Krönung des Tugendhelden”’, in: Gentse Bijdragen tot de Kunstgeschiedenis 24 (1976-1978), 83-86. Saint Paul’s command to the Ephesians6:11-17, that they ‘put on the armor of God’, inspired the Christian Knight iconography.12 Krempel, ‘Tugendhelden’, 85.13 Krempel, ‘Tugendhelden’, 82-93; Rosenthal, Gender, politics, and allegory, 63-112; N. Büttner and U. Heinen (eds.),Peter Paul Rubens. Barocke Leidenschaften, München 2004, 317-320; on the Crossroads allegory, see E. Panofsky,Hercules am Scheidewege, Leipzig 1930.459789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4507-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmett Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdand describes Hercules’s fateful encounter in Emblem XLIIII: ‘The Crossroads ofVirtue and Vice’ (fig. 4).14 While travelingalong a road, young Hercules meets twowomen who ‘[attempt] to pull him downthe path of their respective behavior andlifestyle.’15 Vice, pictured as a bare-breasted Venus, accompanied by Cupid, urgesthe club-wielding hero to take the easypath of ‘pleasures and delights.’16 Virtue,represented by the wise, armored goddess Minerva, encourages Hercules toward the arduous path of righteousness.Because he selected the more difficult,but ultimately more rewarding path ofVirtue, the hero, usually known for hisphysical strength, acquired the attributesof mental fortitude and self-restraint.Observing Drunken Hercules’s undignified appearance and lack of control inthe Dresden painting, it is difficult toreconcile that he was also cited as a figure of virtue in Rubens’s time. Nevertheless, seventeenth-century humanists associated Hercules with the Latin nounvirtus, which denoted ‘manliness, manhood, strength, vigour, courage, [and] excellence.’17 In his Iconologia (1603), CesareRipa cites Hercules as the representationof ‘Heroic Virtue.’ The hero’s lion-skinpelt represents ‘generosity & fortitude ofthe soul’; his club symbolizes ‘reason,Fig. 4 Hadrianus Junius, Emblem XLIIII, ‘The Crossroads ofVirtue and Vice’, in: Emblemata (1565), woodcut, 16.4 cm.By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Archives andSpecial Collections.14 H. Junius, Emblemata, Antwerp 1565, 50, 134-135.15 Junius, Emblemata, 134. For English translations of the Latin text and commentary, see Glasgow University,‘Emblema XLIIII. Bivium virtutis & vitii,’ French Emblems at Glasgow, p?id FJUb044 (accessed 1 January 2020).16 Junius, Emblemata, 134.17 J. Woodall, ‘In pursuit of virtue’, in: VIRTUE. Virtuoso, Virtuosity in Netherlandish art 1500-1700, Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 54 (2003), 7. C.T. Lewis and C. Short, A Latin Dictionary, Oxford 1879.469789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4607-09-20 11:37

Stumbling along the Virtuous Path with Rubens’s Drunken Herculeswhich governs & tames the appetites.’18 Inthe 1611 edition of his emblem book, Ripaincludes an illustration of Hercules wearing his pelt and holding a spiky club (fig.5). In his left hand are the three goldenapples that the laboring hero stole fromthe garden of the Hesperides.19 Those apples symbolize the three heroic virtuesattributed to Hercules: the moderationof anger, the temperance of greed, andthe generous contempt for delights andpleasures.20These positive attributes promptedChristians, Neostoic philosophers, andpean rulers to adopt Hercules inEuro their ideology and iconography. Standingat a crossroads inspired by Matthew 7:1314, Hercules chooses between the narrowpath to Heaven, where devout Christiansstruggle to bear their crosses, and thewide, pleasure-filled path to Hell, wherea finely dressed couple dances towarddamnation (fig. 6). Positioned betweenTruth and Lady World, the pagan demiFig. 5 Cesare Ripa, ‘Heroic Virtue’, in: Iconologia (1611),god becomes a Christian role model. Sevwoodcut.enteenth-century intellectuals studyingthe Stoic teachings of Seneca, a first-cenCourtesy of the Emblematica Online Digital Collection andtury CE Roman philosopher, valued reaThe Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the University of Illison, constancy, equanimity, moderation,nois at Urbana-Champaign.and the acceptance of fate. For Senecaand the Neostoics, Hercules was an exemplum virtutis because he used reason to overcomehis passions at the crossroads.21Themadossier Deugd en ondeugd 18 C. Ripa, Iconologia, Rome 1603, 507. Author’s English translation.19 M. Morford, R. Lenardon, and M. Sham, Classical mythology, Oxford 2014, 572. In Euripides’s version of the myth,Hercules went to the garden, killed the dragon Ladon, and picked the apples himself. According to the traditionrepresented by the metopes at Olympia, the Titan Atlas retrieved the apples for Hercules. Rubens depicted Herculescollecting the apples in a painting at the Musei Reali Torino.20 C. Ripa, Iconologia, Padua 1611, 538.21 M. Morford, Stoics and neostoics. Rubens and the circle of Lipsius, Princeton 1991, 7; Krempel, ‘Tugendhelden’, 90.479789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4707-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmett Fig. 6 Pieter Nolpe after Pieter Symonsz. Potter, Hercules at the Crossroads, c. 1623-1653, etching, 40.1 x 52.4 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, object number RP-P-OB-24.075.Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdMany European rulers chose to associate themselves with Hercules because of his goodjudgment, leadership, and ability to vanquish monsters (i.e. threats to the realm).22 In his design for the triumphal entry of Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, the new governor of the SpanishNetherlands, Rubens portrays the young sovereign in the guise of Hercules Prodicus (fig. 7).Wise Minerva pulls Ferdinand toward the virtuous path and his resultant military victoryat Nördlingen.23 Although he dutifully chose Virtue, the Cardinal-Infante looks back long-22 A. Georgievska-Shine and L. Silver, Rubens, Velázquez, and the King of Spain, Burlington 2014, 90-95.23 J.R. Martin, The decorations for the Pompa Introitus Ferdinandi, Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard 16, Brussels1972, 206-207.489789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4807-09-20 11:37

Stumbling along the Virtuous Path with Rubens’s Drunken Herculester Peter Paul Rubens, HerculesProdicus, in: C. Gevartius, Pompa introitus Ferdinandi, pl. 39,(1639-1641), etching/engraving, 31x 26.2 cm.Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, objectnumber RP-P-OB-70.278.Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdFig. 7 Theodoor van Thulden, af- ingly at the figures of Venus and Bacchus. Like Hercules, the ruler is tempted by Lust andDrunkenness.At first glance, Rubens’s pendant paintings represent a dichotomous moralizing messageabout the consequences of Virtue and Vice. However, a strictly negative reading of DrunkenHercules or an entirely positive interpretation of The Coronation of a Hero ignores the relationship between the figures in each composition.24 Lisa Rosenthal argues that the physicalembodiment of allegorical concepts complicates and subverts the allegories depicted.25 InThe Coronation of a Hero, for example, the virtuous knight seems conflicted: he draws Victo-24 Rosenthal, Gender, politics, and allegory, 75; Heinen, Barocke Leidenschaften, 316-320.25 Rosenthal, Gender, politics, and allegory, 70.499789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 4907-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmettry closer with a hand on her waist, while averting his gaze and leaning away from her.26 Thehero hesitantly embraces Victory, because she so closely resembles temptation: the wingednude is just as enticing as Lust, her seated twin. Here, Rubens paints a man with a loose gripon victory over vice. At any moment the wary hero could succumb to lust, veering off the virtuous path as easily as Drunken Hercules. Maintaining a virtuous lifestyle was difficult, andlapses in temperance were inevitable – as Hercules’s stories make clear. Rubens’s pendantschallenge the idea that a man exclusively chooses either a life of Virtue or Vice. Even themost well-meaning seventeenth-century men could expect to falter along their own paths.Rubens’s Humanized Hercules Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdHercules was the son of Jupiter, the king of the gods, and the mortal queen Alcmene. Whilethe hero’s supernatural strength was undoubtedly part of his divine inheritance, it is unclearwhether his penchant for wine and women stemmed from his pleasure-loving father or hishuman mother. As an artist, antiquarian, and humanist, Rubens studied visual and textualsources recounting Hercules’s triumphs and follies. Rubens’s knowledge of the demigod’slimitations is evidenced in his oeuvre, in his personal art collection, and even in the artist’sdecoration of his own home in the center of Antwerp.During his travels in Italy from 1600 to 1608, Rubens studied, sketched, and collectedimages of Hercules. At the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, the artist drew the Farnese Hercules, athird-century CE marble copy of a bronze statue by Lysippos (fig. 8).27 In his ‘Theory of theHuman Figure’ (c. 1608), a posthumously published essay from his theoretical notebook,Rubens identifies the Farnese Hercules as ‘a work which is perfect in all its points and whichcharacterizes the greatest strength.’28 Despite his impressive physique, the Farnese Herculesrepresents a bone-weary hero, exhausted from his labors. The towering figure leans againsthis club. His head droops in the direction of his downcast eyes. The fatigued-hero motifmust have appealed to Rubens, who owned a carved gem featuring Resting Hercules. Theintaglio survives in a description written by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc around 1622:[6] Hercules, seated on a rock under a tree, melancholic, his head supported on his elbow, his faceresting on the back of his right hand, his right foot placed on top of an altar against which stand thehead of a wild boar and his club on top of it. At his feet lie the three apples of the Hesperides and hislion skin beside his seat. Intaglio.2926 Ibidem, 71.27 D. Jaffé and E. McGrath, Rubens. A master in the making, London 2005, 92-93.28 P.P. Rubens, Théorie de la Figure Humaine, ed. N. Laneyrie-Dagen, Paris 2003, 54. Author’s English translation.29 K.L. Belkin and F. Healy (eds.), A house of art. Rubens as collector, Antwerp 2004, 294. In 1619, Rubens began hiscorrespondence with Peiresc, a French scholar, antiquarian, and collector. By 1622, they decided to publish a bookon the most impressive surviving gems: Rubens would design the illustrations, Peiresc would write the descriptions.509789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 5007-09-20 11:37

Stumbling along the Virtuous Path with Rubens’s Drunken HerculesFig. 8 Glykon, copy after Lysippos, Farnese Hercules, c. 216CE (original from fourth century BCE), marble, 3.17 m.Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Photo Credit: Scala /Art Resource, NY.Exactly when Rubens acquired the gemis unknown; however, he may have purchased it during his eight-year stay in Italy.30 During that time the artist likelyencountered several ancient Roman sarcophagi featuring drunken Hercules. InRome, specifically, a relief in the Mattei collection inspired Rubens’s painting of theinebriated hero supported by two satyrs.31Rubens’s treatment of Drunken Hercules echoes the vulnerability and humanity that he saw in artworks such as theFarnese Hercules, his Resting Hercules gem,and reliefs from antiquity. Following hisown advice from his treatise On the Imitation of Statues (c. 1608), Rubens transforms the Farnese Hercules from marbleto flesh, ‘[distinguishing] material fromform, stone from figure-drawing [ ].’32 Inhis Drunken Hercules, Rubens softens the‘steep descents into blackness and shadow’ that characterize the Farnese Hercules’s stone musculature, animating thehard planes of his body with fleshy, translucent layers of color.33 Rubens’s paintedhero also has thicker limbs and a shorter torso. Most remarkably, in his transformation of the classical prototype, Rubenspainted his Drunken Hercules with hair onhis chest, armpits, and groin – a featureomitted from most ancient sculpture, butone that draws attention to the figure’shuman nature. Completing the incarna-Themadossier Deugd en ondeugd Unfortunately, the Gem Book was never finished. Belkin and Healy, A house of art, 261-262.30 Ibidem, 294.31 McGrath, ‘Rubens’s house’, 265.32 P.P. Rubens, On the Imitation of Statues, translation J. Fairweather, in: Wyhe (ed.), Rubens and the human body,99.33 Rubens, On the Imitation of Statues, 99.519789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 5107-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmettFig. 9 Peter Paul Rubens, detailof garden pavilion with Hercules bust, in Rubens and his sec-ond wife Helene Fourment in thegarden, 1631, oil on panel, 97.5 130.8 cm.Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich,Photo Credit: Erich Lessing / ArtResource, NY. Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdtion, Rubens gives his Hercules the ruddy cheeks and red nose of a drunkard.The artist lived with multiple contrasting examples of Hercules’s virtues and vices. Inaddition to the pendant paintings, the complicated hero decorated Rubens’s house and garden. In a painting dated to 1631, a bust of Hercules appears in an elevated, central positionin Rubens’s garden pavilion (fig. 9). Similarly, a plaster cast of the hero’s head sat over a doorway inside the artist’s home (fig. 10).34 In Jacobus Harrewijn’s 1684 print, the pavilion housesa full-length statue of Hercules, visible through the large, center archway of Rubens’s Italianate portico (fig. 11).35 In all likelihood, Rubens’s student Lucas Faydherbe sculpted the figure between 1636 and 1640 after his master’s design (fig. 12).36 This over-life-sized Hercules,reminiscent of the Farnese Hercules, finds peace in Rubens’s garden.37According to Ulrich Heinen, Rubens created a Lipsian Stoic garden, a retreat from theworries and uncertainties of the chaotic world, where visitors could regain clear judgmentand reason.38 The most important feature of the Stoic garden is its relationship to the outside world: it must have clear boundaries.39 Along the eastern border of his property, where34 Muller, ‘Rubens’s collection in history’, 21.35 The full-length Hercules statue also appears in the Rubens House pavilion in the background of Gonzales Coques’s Portrait of a Couple in the Park from around 1655 to 1660 at the Staatliche Museen in Berlin.36 U. Heinen, ‘Rubens’ Garten und die Gesundheit des Künstlers’, in: Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch 65 (2004), 103.Faydherbe sculpted busts of Hercules, too. See H. de Nijn, H. Vlieghe, and H. Devisscher (eds.), Lucas Faydherbe1617-1697, Mechelen 1997, 141-142, no. 21, 187-189 (bust Omphale), nos. 59-60, 194-195, no. 67.37 Heinen, ‘Rubens’ Garten’, 103-106.38 Ibidem, 99.39 Ibidem, 100.529789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 5207-09-20 11:37

Stumbling along the Virtuous Path with Rubens’s Drunken Herculesthe pavilion stands, Rubens had a wall built between his garden andthe shooting ranges of the Kolveniers (Arquebusiers) guild, Antwerp’scivic guard equipped with musket-like firearms. In effect, the Hercules statue turns his back on warfare and violence, represented by theriflemen.40To enter the artist’s garden from the west, visitors must traverse thecourtyard and walk under the monumental portico that Rubens designed. Over the left and right archways, pairs of male and female satyrs hold tablets, inscribed with lines from Juvenal’s tenth Satire (fig.13). The quotations in gilt lettering functioned as the lex hortorum, orgarden law, which conveyed the code of conduct and philosophy of thegarden.41 In this case, the excerpts from Juvenal’s Satires promote theStoic values of moderation, tranquility, and acceptance of fate. The inscription on the right instructs guests to ‘[ ] pray for a sound mind inFig. 10 Bust of Hera sound body. Ask for a heart that is courageous, with no fear of deathcules decorating a that is unfamiliar with anger, that longs for nothing.’42 Rubens knewdoorway in Rubens’sthat the passage continued: ‘Ask for a heart that prefers the troubleshouse (before it wasdismantled duringand grueling Labors of Hercules to sex and feasts and downy cushthe reconstruction ofions of Sardanapalus.’43 In Rubens’s garden, it is preferable to toil like1938), plaster cast.the demigod than to overindulge in worldly pleasures like the Assyrian king.Rubenshuis, Antwerp.Familiar with the entirety of the tenth Satire, Rubens and his fellowLatin school graduates may have discussed how Juvenal promoted themodel of Democritus, the laughing philosopher.44 Seneca, in his dialogue De TranquillitateAnimi (‘On tranquility of the mind/soul’), explains:Themadossier Deugd en ondeugd We ought therefore to bring ourselves into such a state of mind that all the vices of the vulgar maynot appear hateful to us, but merely ridiculous, and we should imitate Democritus rather than Heraclitus. The latter of these, whenever he appeared in public, used to weep, the former to laugh: the onethought all human doings to be follies, the other thought them to be miseries.45For Seneca, it is better to laugh at the world’s ills than to weep, because with laughter thereremains hope for improvement. Perhaps it was with Democritus’s hopeful laughter that40 Ibidem, 104.41 B. Uppenkamp and B. van Beneden, Palazzo Rubens. The master as architect, Antwerp 2011, 92.42 Ibidem.43 Ibidem.44 Heinen, ‘Rubens’ Garten’, 134-138. In 1603, Rubens painted Democritus and Heraclitus for the Duke of Lerma.45 Seneca, ‘Of Peace of Mind’, 15:2, in: Minor Dialogs Together with the Dialog ‘On Clemency’, translation A. Stewart,London 1900, 250-287.539789087048785.pinn.JDZE2020.indb 5307-09-20 11:37

kendra grimmett Fig. 11 Jacobus Harrewijn, after Jacques van Croes, Rubens House in Antwerp, 1684, engraving, 29 35.8 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, object number RP-P-OB-55.443.Themadossier Deugd en ondeugdRubens approached the figure of Hercules. In the courtyard between the portico and thegates to the city street, Rubens included a Drunken Hercules on the façade of his studio(fig. 14). The inebriated hero appears in the upper-right section of the frieze, closest to thestreet exit to Wapper. Like the gilt inscriptions, Hercules is supported by a pair of satyrs.Rubens and his guests might laugh at the demigod’s foolishness in the manner of Democritus rather than weep for his failure like Heraclitus.Expanding on Heinen’s interpretation of the Hercules statue in Rubens’s pavilion, I propose that the Drunken Hercules frieze may represent the mind and body of a man who needsto be rejuvenated and returned to reason in the garden. Located beyond the garden’s boundaries, closest to

In the French translation of the inventory, or 'Specification', the paintings are described as: 'Vn cheualier Chrestien couronné de la victoire sur fond de bois' and 'Vn Hercule enyuré sur fond de bois'. Fig. 2 Peter Paul Rubens, The Cor-onation of a Hero, c. 1613-1615, oil on panel, 221.5 x 200.5 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische .