Transcription

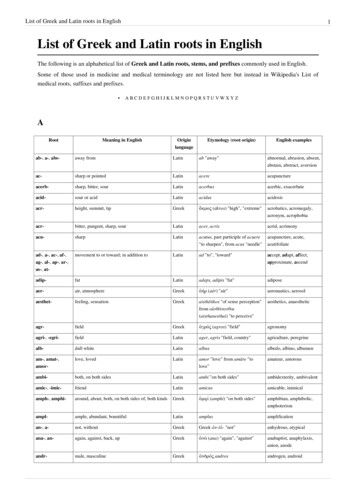

Art in LatinAmericaThe Modern Era, 1820-1980Dawn Adeswith contributions by Guy Brett,Stanton Loomis Catlin and Rosemary O'NeillYale University PressNew Haven and London 1989

ContentsSponsors of the ExhibitionAdvisory PanelExhibition CommitteeForewordAcknowledgementsLenders to the ExhibitionIntroduction1. Independence and its Heroes2. Acadern.ies and History Painting3.i Traveller-Reporter Artists and the EmpiricalTradition in Post-Independence Latin Americaby Stanton Loomis Catlin3.ii Nature, Science and the Picturesque4. Jose Maria Velasco5. Posada and the Popular Graphic Tradition6. Modernism and the Search for Roots7. The Mexican Mural Movement8. The Tall er de Grafica Popular9. Indigenism and Social Realism10. Private Worlds and Public Myths11. Arte Mad{/A rte Concreto-Invenci6n12. A Radical Leap by Guy Brett13. History and IdentityNotesManifestosBiographies by Rosem.ary O'NeillSelect BibliographyPhotographic 195215241253285301306338360361362

1Independence and itsHeroesof the Independence movem ents in the Spanishcolonies of America gave birth to new countries, new politicalo rders and to lasting debates about national identity , but not immediately to any flo wering of the arts. Material existence, bothduring and after the wars against the Spanish colonizing powers ,was too precarious, the general state of affairs too unstable, for theformation of artistic communities. No claims were made for any'movement' in the arts that might have embodied the political idealsof Independence, in the way that nee-classicism in the hands ofDavid had for the French Revolution. Although nee-classicism,whose influence was felt in the Academy in M exico by the end ofthe eighteenth century, was associated with the reforming currentsof thought in intellectual circles, there was little opportunity for itsdevelopment. 'Twenty years of civil war and insurrection', theEnglish traveller and collector William Bullock wrote in 1823, 'haveproduced a deplorable change in the Arts . . today, there is not asingle pupil in the Academy . . '. 1'By 1830, nearly every part of the sub-continent presented a spectacle of civil war, violence or dictatorship ; the few writers and intellectuals were either tossed to one side or forced into battle. '2 Thesitu ation, however, was a little less dire in the visual arts, in thatofficial and popular demand for portraits ensured some livelihoodfor painters. If there was not a flowering, there was at least some response in the visual arts to the drama, turbulence and excitement ofpolitical life in Latin America in the first half of the nineteenthcentury.In fact, the visual art that was produced at the time of Independence has taken on an almost disproportionate importancesubsequentl y, not only as 'authentic' historical do cument, which isthe way it is usuall y presented in Latin America now, but also aswitness to and assistant in the process of construction of a nationalidentity. For Independence, whatever succeeded it in terms of discord and strife, and however far its ideals became distanced frompolitical reality, remained by far the most important moment forthe new nations that emerged; representations of its heroes andmartyrs have become talismans or icons signifying those beliefs,and reinterpreted with reverence, or w ith irony, by artists in thetwentieth century for w hom national or Latin American identity incultural and political terms remains an unresolved and thereforepotent issue. The contemporary imagery of Independence: portraits of its heroes, leaders and martyrs [Pls 1.2,3, 4,5,6,9, 10] , picTHE SUCCESS7l.1D eta il of Pl. 1.7.1.2 Antonio Salas (attributed) , Portrait of Simon Bali1829, oil on can vas, 59x47 cm., Collection OswaldoViteri.

.on,:mous Polica rpa Salavarrieta Go es to H er19th century, oil on canvas, 76x95cm ., M useo·oml. Colombia.rn-u.1.nnlimr,11 Sa/Q.uarrietaSac.rjfic11J11 p. lor '1)ia:iiolu rn e.vta ;,laza rltlJIWe,7rinl qc/817.su mrmoria eternicctt1tn· nozofros.'Icf.,ui,,a rrrsuer,t oeyolou.}lofo !!!onymou , Exewtion of th e H eroine Rosa Zara te ande la Pe,ia (in T 11r11aco), 1812, oil on canvas ,· - 6cm. , useo de Arte M oderno, Casa de la. .,. Ecuacorian a Q ui to .·. oaymous, Poma it of General Ota rnendi , 19thry oil o n tin, 35.5 x25 cm ., Museo Jacinto Jij 6n yano, Quito.

INDEPENDENC E AND ITS HEROEStures of recent historical events and victories against the Spanisharmy, allegorical scenes and personifications of America or of individual republics [Pls 1. 7,8], was produced in a variety of styles,ranging from the neo-classical to the nai:ve. These works involvebo th a continuation and a rejection of traditions es tablished duringche colonial epoch.For three hundred years, since the Spanish invasions of the earlyixteenth century, Spain (or in the case of Brazil, whose historycook a different turn in the nineteenth century, Portugal) had ruledfr om Europe, through a succession of viceroys, the different proinces into which Spanish America was divided; high official positions were reserved exclusively for Spaniards from Spain, althoughcreole (criollo) society (that is, Spaniards born in the New World)ettled in those provinces and became rich. It was members of thisclass who were largely instrumental in achieving Independence.The majority of the population, at least in che And ean counrries an1. 7 Anon ymous, A llegory of the Departure of Dom Pedro 11for Europ e after the Declaration of the Republic, 1890, oil oncanvas, 82x103cm., Fundaqao Maria Luisa e O scarAmericana, Sao Paulo.1. 8 Jean-Baptiste Debret, Landing of Doiia Leopoldi11a,First Empress of Braz il (study) , n.d., oil on canvas,44. Sx69 .S cm. , Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio deJaniero.j!JI ',) · .t -,.···olilll -('1, ·· 71-I· '.A;.'l· . .,H { \ "- " '.;"''. ,, .,. cIr J-t ,,

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROESFrancisco de Paulo Alvarez, Riding ro Bogora 111/·11, rh eario11 Arni)', 19th centur y oil on canvas, 65.S x116 cm. ,. useoacional, Colombia.l. l (facing page)C ircle of the Master of Calamarca,·c Titicaca School, A rchangel with Gt111 , late 17thrury, oil on cotton, 47x3J cm ., New Orleans MuseumJo e arfa Espinosa . B(lftlc ,f .\ l.im 'ai/," Cm rle, 1878,n c;uwas, 90 127cm. , Musco acio11 .i l. Co lombia.in Mexico and Central America, was 'Indian' - a term we have perforce to use, since there is no other single term to describe theoriginal peoples of the continent, but one which imposes a spuriousunity only demanded by the colonizing process itself 3 With the exception of those people who remained physically and geographically out of reach, the populations became Catholic, althoughbeliefs were frequently syncretic, involving elements of the old religions mingled with the new and with significant local variations.Out of this mestiz o, or mixed, culture sprang a flourishing popularart, with paintings (on cloth, wood, tin, skin, paper and canvas) andcarvings in wood and wax, alabaster and stone. At the levels of bothpopular and official art, the Church was the dominant factor , andwith the exception of society and campaign portraits, which became extremely popular in the eighteenth century, the visual artswere almost exclusively at the service of the Catholic religion.Occasionally a strikingly original talent arose, like Diego Quispe inseventeenth-century Cuzco , or wonderful transformations ofChristian iconography occurred, as in the motif of the Angel with aGun, again in the Cuzco school. Usually anonymous, these paintings depict divine figures like the archangels Michael or Barachiel(Uriel), dressed in the flamboyant secular attire of the seventeenthcentury dignitary - or perhaps the viceroy himself - carrying,prominently, a musket, their poses based on military handbooks ofthe period [Pl. 1.11]. Other Cuzco school paintings depict saints orangels in more baroque military garb. 410

IND EPENDENC E AND ITS HEROES1.12 Anonymous, Virgi 11 of th e Hill , before 1720, oil oncanvas, Casa N acional de M oneda, Poto f.Paintings of the Virgin in Peru and Bolivia, w hich often include aportrait of the donor, share with these a remarkable elaboration ofdecora tive detail, especially in the clothes, often embroidered infine gilt. It is a decorativeness that has little to do with the sinuousrococo of eighteenth-century Europe, favouring rather a symmetrical and hieratic stiffness . Possibly the labour spent on paintingthe cloth carries some of the dignity textiles possessed in the Incaand pre-Incaic cultures (Paracas and N azca, for instance) , wherebythe new religion is endowed w ith some of the values of the previouscultures . One of the most significant images is that of the Virg in ofth e Hill of Potosi, w hose skirts spread to become the hill of the silvermines, thereby taking on the identity of Pachamama, the Andeanearth and creation goddess [Pl. 1.12].With Independence, the Church's role as patron of the visual artslessened, althou gh the battle between civil and ecclesiasticalauthorities, sparked by Independence, continued . But portraits ofthe leaders and heroes of Independence sometimes take on theaspect of a votive image, now in the service of a secular idealism.T he ideology oflndependence w as fundamentall y that of the Enlightenment: 'The revolutionary m essage came from France andN orth Am erica under the priest's cassock, and in the minds of thecosmopolitan statesm en to sharpen the discontent of the edu catedand well- bred Creoles, governed from across the seas by the law oftribute and the gallows,' 5 wrote Jose M arti, the Cuban w riter andrevolutionary who died in action on the eve of Cuban independencein 1895.Simon Bolivar, from a wealthy creole family long established inCaracas, spent periods of his youth in Europe, w here he witnessedNapoleon's coronation. H e was thoroughly edu cated in Enlightenment thought, fa miliar with Rousseau, Mirabeau and Voltaire (hisfavo urite author), in common with other American revolutionarythinkers of the time, including Hidalgo, w hose abortive insurrection of 1810 is taken as the start of the M exican stru ggle for independence. Bolivar was in turn immensely admired by liberalEurope. Byron nam ed his schooner BoUvar, and hesitated betweenjoining the struggle for independence in South America or inGreece. Bolivar was the subj ect of numerous sympathetic caricatures, as well as often being compared w ith N apoleon. Su ch comparisons frequently find their way into the Bolivarian iconography,as in the 1857 portrait by the Chilean artist Arayo Gomez, whichplaces Bolivar on a w hite horse, rearing against a background of theAndes rather than the Alps, in direct reference to David's portrait ofNapo leon Crossing th e A lps. The earliest such use of D avid's dramatic equ estrian portrait was probably an 1824 engraving by S. W .Reynolds, which adds the nam es 'Bolivar ' and 'O'Higgins' to ·the'Bonaparte' inscribed in the Alpine ro ck. Bolivar rej ected suchcomparisons, however, saying, 'I am not N apoleon, nor do I wishto be him; neither do I wish to imitate Caesar. . the title of Liberator is superior to the m any I could have received. ' 6 (He had beenhonoured with the title 'Libertador ' in M erida, Venezuela, inJune12

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROES1813.) Bolfvar's terms of reference were strikingly and persistentlyEuropean, borrowing especially from the Enlightenment the language of classical republican ideals . He described himself, for instance, as having to play the role of Brutus to save his country, butbeing unwilling to play that of Sulla.Disagreement about the form new governments were to take,and deeper conflicts that had been both masked and unleashed byIndependence, led to continuing violence. 'It is easier for men to diewith honour than to think with order . It was discovered that it issimpler to govern when sentiments are exalted and united, than inthe wake of battle when divisive, arrogant, exotic and ambitiousideas emerge, ' 7 wrote Marti. Thereafter, for the next half-century,'An extraordinary procession of eccentric despots, mad tyrants andhalf-civilized "men on horseback" sweeps across the historicalscene'. 8Bolivar was faced with the collapse of his dream of a peaceful andunited federation of Gran Colombia; the Republic he managed tocreate, out of the former viceroyalty of New Granada and part ofthe viceroyalty of Peru (now the nations of Colombia, Venezuela,Ecuador and Panama), was disintegrating amid conspiracies, rebellions and campaigns to discredit Bolivar. He resigned as Presidentin 1830, and later that year died at Santa Marta on his way intovoluntary exile, aged forty-seven. He had written to his closestcompanion at arms, General Sucre, 'It will be said that I have liberated the New World, but it will not be said that I perfected thestability and happiness of any of the nations that compass it. '9Marti blamed Bolivar for attempting to impose foreign notions onan alien reality:America began to suffer, and still suffers, from the effort of trying to find an adjustment between the discordant and hostile elements it inherited from a despotic and perverse colonizer, and theimported ideas and forms which have retarded the logicalgovernment because of their lack oflocal reality. The continent,disjointed by three centuries of a rule that denied men the right touse their reason, embarked on a form of government based onreason, witho ut thou ght or reflection on the unlettered hordeswhich had helped in its redemption . . 10Indeed, as this last passage hints, the problem of the type of government to be adopted conceals a more radical problem: that of a basicalternative between the Indianization or the Westernization ofAmerica. The very term 'New World' belongs irrevocably to thelatter, as does the term 'American Spain', a concept accepted byBolivar and other revolutionary thinkers , which immediately alertsus to the presence of a Western discourse.Very few of the innumerable tracts printed during the Independence struggles were addressed to the Indian inhabitants, let alonewritten in a native language. One of the few exceptions was, significantly, addressed to the indigenous people of a neighbouring13

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROEScountry, for transparent political reasons: Bernardo O'Higgins, the'Supreme Director of the State of Chile', as he titled himself,addressed the 'Natives of Peru' in Quechua, exhorting them to invite him and his army of liberation in, to help their own fight forindependence. 11On the whole it was in those countries where the original inhabitants had possessed a civilization that was recognizably advancedaccording to European standards, with writing, stone architecture,painting and sculpture, elaborate tax and tribute systems and clearlydefined social and ritual hierarchies, that there had been continuingresistance to Spanish colonial rule. Active struggles for independence in colonial America cannot be subsumed automatically intothe successful movement against Spain of the early nineteenthcentury, but they provided important precursors for it. The mostfamous of the native insurrections that preceded Independence wasthat ofTupac Amaru. A descendant of the Incas, Tupac Amaru hada grand political vision of government by the Indians and the restoration of their lands. His campaign of1781, which had much popular support, ended in his capture and death, and only two portraitsof him have survived: one by the Indian Simon Oblitas, fromCuzco. These were probably painted from life, and intended, aswere so many such portraits of revolutionary leaders, to spreadTupac Amaru's image among the people and keep his memoryalive. It is not surprising that so few have survived, given that suchportraits were 'considered punishable and witnesses of subversiveactivity'. 12There were, however, conflicting ideas and interests among indigenous restoration movements. Pumacahua, also of Inca blood,was Tupac Amaru's bitter enemy, and helped defeat him at thebattle ofTinta. He espoused a conservative ideology, and, althoughcalling himselflnca, was at the same time sufficiently valued by theSpanish authorities to be named by the Viceroy in 1807 'PresidenteInterno de la Real Audiencia de Cuzco', the highest position an indigene reached under viceregal government. In 1814 Pumacahuajoined what was the most formidable uprising against the Spanishin Peru until San Martin, being finally defeated by General Ramirezon the heights of U machiri.Between 1781 and 1814 ideas of establishing an Inca monarchy remained very much alive; there was in 1805, for instance, a plan to restore the Inca socio-political structure, the Tahuantinsuyu, and tocrown an Inca. The influence of these ideas was still felt when laterdebates concerning the form of government turned to the possibility of monarchy. At the Congress of Tucuman in Buenos Aires in1816, Belgrano promoted the idea that a new government should beinspired by the Inca empire, an idea bitterly opposed by others whomocked 'la monarqufa de las ojotas' (the monarchy of sandals). 13Teresa Gisbert examines the iconography associated with ideasof the restoration of the Inca dynasty in the context of Independence, and reveals the odd legitimation it offers to Independenceheroes, eventually fading into nostalgia [Pl.1. 13). San Martin, who14

DOSiMON BOLIVAR.Y &l c nfro c.OTt10.E.10 ,Vuestl'11 eflllic .Seflor. 4 \\ni ,TernoA n tf ltf1"'NI ctlorio 'A O\L dl\t tu j*nl .ll. vencedoT\n!.ali!&!'l le,""on tortl'\ldl 01'6TlaUTf1 -J-"Ja.,&,1,,'f "':Jt ,64'/;, Ao, ,,-{J'2 ,(P.f.r,,.,7-, .;J1.13Anonymo us, A llegorical shield in honour of BoUvar, 1825, 108x102 cm., Institu co N acional de C ultura-C usco; M useo Hisc6rico Regional.

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROES1. 14 Ano nymous, Allegorical Th eme: Homage to Bol(var;' iva BoUvar; Viva Bol(var', 19th century, engraving,Fundaci6n John Boulton, Caracas .was, it seems, not averse to accepting a crown, is depicted in onebiombo (screen) at the end of a sequence oflnca kings; Bolfvar, whowas averse to it, is also shown in a lienz o (canvas), his head paintedover that of Carlos III, in a sequence of monarchs beginning withthe Inca rulers, and with fellow Independence leaders, includingPaez and Sucre, superimposed over other Spanish kings. Sahuaraura's Recuerdos de la Monarqufa Peruana o Bosquejo de la Historia de lasInca (1836-8, published Paris 1850) portrays the genealogy of theInca, in the tradition that extends back to Guaman Poma de Ayala'sNueva Cor6nica y Buen Gobierno of the early seventeenth century, todemonstrate the author's royal blood. But, like the engraved copiesof the Inca dynasty made for European travellers in the nineteenthcentury, Sahuaraura's images lack the polemical and revolutionaryimport they would have had at the time of Tupac Amaru, havingeven in a sense become safely picturesque. As Gisbert writes:The characteristics of autochthonous art of the colonial era bearwitness to the existence of an Indian nation within the viceregalstructure, fighting to maintain its identity and to remain in evidence. In the eighteenth century the natives channelled their aspirations into politics, only to see them wrecked by the collapse ofthe rebellion of 1781; from that date what had been combativeand committed art (paintings, architectural fa ;:ades, etc.) turns tonostalgic reminiscence, even though the creole patriots did notidentify themselves with Indian ideology and employed thesevalues - which they knew by the light of encyclopedists morethan through their own experience - within a somewhat lyricalsetting. 14'/ -". N .- , / / ,y"/4 -' /2,o'o/'NN' ;r,-,-//,/,;.,,, ,;.,,a/4./,.:r,,,, ".r··,,JI"'1'/MO/,m/J;,//,. n,l.15,-r,.,y;,,,.A. Leclerc, Si111611 Bo!(JJnr, 1819, lithog raph , Bogota.By the time the creole patriots had driven out the Spanish, it waspossible to invoke the figure of the Inca as part of a symbolic or allegorical system indicating national unity. A silver candlestick struckin Britain to commemorate British support for Independence unitesthe three figures of Bolfvar, Britannia and an Inca. An engraving inthe Boulton Foundation in Caracas shows a ring of figures including Indians, mestizos and creoles dancing round a bust ofBolivar [Pl. 1.14]. Other engravings show the Indians, significantly, in the background. One by Dubois, intended for populardistribution in America, depicts a possibly mulatto father holdingup a framed engraving of Bolfvar for his family's admiration, whilein the distance a troop of Indians in single file, with the characteristic erect and squared-off feather head-dress with which theywere usually represented at the time, emerging from behind achurch carrying a flag, presumably symbolic of national unity .Underneath is the inscription 'Aquf esta su Libertador' (Here isyour Liberator) [Pl. 1.16]. The engraving of Bolfvar is clearly basedon the earlier widely disseminated engraved portraits by Bate, orLeclerc [Pl. 1.15], where he has curly hair growing over his foreheadand a moustache. 15Representations of America have from the colonial period ontaken the form of an indigenous woman. 16 An interesting variation16

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROESon this occurs in the canvas painted by the Bogota artist Pedro JoseFigueroa, Simon Bol var, Liberator and Father of the Nation [Pl. 1.17] ,co celebrate the final independence of N ew Granada following thebattle of Bo yaca on 7 August 1819. The picture was presented toBolivar in the main square of Bogota during the victory fiesta on 18eptember. The young Republic is shown as an Indian womanwearing the upright feather head-dress already noted, carryingbows and arrows and seated on the head of a mythical cayman. Shetands in relation to Bolivar as daughter (he is named Father of thePatria). 17 However, she also - unlike many personifications ofAmerica which show her as naked or lightly draped - is dressed asand wears the pearls and jewels of a European, and her features areat most mestizo ; her gesture is clearly derived from Christianiconography, and she presents something of the aspect of a virgin oraint.T he most familiar images of Bolivar, and those which cast their influence over many dese;riptions of him, such as Marti's ('that man ofhigh forehead above a face devoured by eyes indifferent to steel ortempest . '), are those painted by Gil de Castro and by Jose MarfaEspinosa. Espinosa painted Bolivar from 1828, while he was inBogota, and made pencil sketches from life, including one justbefore he died, showing him worn and prematurely aged [Pl. 1. 22].He continued to make numerous portraits of Bolfvar after hisdeath, for foreigners and his countrymen, the grandest of which ische 1864 portrait (Bolfvar: Portra it of the Liberator) [Pl. 1.18], with itsinsistent echoes of Napoleon, with arms crossed and an elaborateofa behind. This large painting now hangs in solitary pride of placein the central Cabinet room of the Government Palace in Caracas.By contrast with this , Gil de Castro's portrait of Bolivar, and thatof Olaya, the martyr of Peruvian independence [Pl. 1.20], still harkback to a colonial tradition, with a lengthy inscription carefully lettered on to a framed plaque, although the red banner above the subj ect's head clearly at the same time announces him as a modernrevolutionary. The attributes are carefully arranged in each: theglobe and writing material on the desk in the portrait of Bolivar [Pl.1.19] refer to the extraordinary geographical scope of his achievement, and, having ridden with his army across a continent, hisextraordinary energy in writing tracts and issuing edicts to the libera ted countries. Gil de Castro, a mulatto who had painted societyportraits before the Independence movement, joined the struggleenthusiastically, and entered Santiago with the liberating army.T hence he came with San.Martin 's army to Lima, where he became'Primer Pintor de! Go bierno del Peru ', and designed the army's uniforms. He painted most of the heroes of Independence, and reerved for them, and for heads of state, the full-length portrait,w hich in his hands takes on something of a votive image. Thefaintly primitive, chiselled neo-classicism of his portraits of Bolivarmaintains a delicate and appropriate balance between the local andc-he European: it is a 'provincial and festive version of neo-classi171.16 Dubois, H ere is Yo 11r Liberator, 19th century, ha ndcoloured engrav ing, Coll ecti on Bosque C arda, Ca racas.!'1'''1:' U'. ., 1 .' p ·1,fi· '. "'. . '. .L. ,,.!,. · ··1:,:;( . ·1,.·,;,,. ·11'![; (::' . ".' ·. I,l\. ·-;. r- -. '11!:.,.-.Ai . , . .,.,,r-. ,/' : \' \ ·t\.r-mr - \ ·'-'-·t 1 "11!. }::-. H,. (1 1.17 Pedro Jose Fi g ueroa , S i111611 BoU/!a r, Liberator andFather of th e Na tion, 1819, oil on canvas , Quinta deB olfva r, C olombia .

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROES1.1 8 J ose Maria E pin osa. B,,/,, a r: PCl1·m1i11864, Palace of Miraflores, Caracas.,f rl,cLihcraror,1.19 J ose Gil de Cast ro. P,,rrrair f 80 /(1 ,ar in Bo.l!ortf.1 30 . oi l on ca nvas.cism'. 18 His Portrait of Simon Bolfvar in Lima, of 1825, was sen t toBolfvar's sister in Caracas; its relative simplicity and directnesspleased Bolfvar [Pl. 1. 21].The production of the images relating to Independence co uldnever be a neutral or objective matter, particularly in the climate ofviolence and discord that followed it:. the interpretation of recent history was repeatedly a 'mirrorof discords'. Faced with each version of the facts as it arose . .the artists were called on to illustrate the thought of the historianor the political group to w hich they adhered. T hus the foregoingserves us as a basis for understanding the circumstances and the1.20 J ose Gil de Castro , The Marryr Olaya , 1823 , oil onca nvas , 204x134cm. , Mu seo Nacional de Historia, Lima .18

II J ilil '·-·' , :!-. , 1 , .INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROESconjuncture in which the portraits of leading figures and thecommemorative works bore witness to the various projects ofnationhood. Linked with the emergence of conflicting politicalproposals (basically between a central and a federal system), theimages not only took note of short-term changes in the politicalor military scene (memory) , but also, through the recovery ofcertain antagonistic figures (Hidalgo v. Iturbide), traced the different ideological courses which the country was later to follow(the sense of history). Undoubtedly the decisive weight of thepast, containing the genesis of the idea of nationhood, gave sanction to the deeds of the present and launched the ideals of thefuture. 19The antagonism between different interests and ideals, between dif·erent models of the projected 'new nation' to follow Independence, represented in the passage quoted above by the phrase Hidalgo v. Iturbide', leads on to some of the issues raised earlierbut now in the specific context of Mexico, and in particular thequestion, whose Independence was it?Don Miguel Hidalgo , parish priest of Dolores, initiated theuprising against Spain on 16 September 1810, with the famous 'gritode Dolores': 'M y children, will you be free? Will you make theeffort to recover from the hated Spaniards the lands stolen from:·our forefathers three hundred years ago?' 20 His revolutionary proramme had three main points: the abolition of slavery, the supression of 'el pago de tributo ', and the restoration of land to theIndians. He gathered massive popular support among the Indiansand the rural poor, and shortly led an army of 100,000 men, with5 cannon, and in addition controlled one of the few printingresses in M exico . H e issued two decrees from Guadalaj ara, on 5and 6 December 1810, the first ordering the devolution of lands tothe indigenous people, the second the abolition of slavery, paymentf tribute and the 'papel sellado', signing himself 'Generalfsimo de:\merica'. 21 But almost none of the liberal creoles joined him; hewas defeated, formally stripped of his priestly powers, and shot on 1:\ugust 1811, although his movement was continued by supporterstl.ke Morelos.When Independence came, it took a very different form, bringmg neither the liberty nor the equality Hidalgo had fought for , andleaving the issue ofland to explode again a hundred years later in the. . lexican Revolution of 1910. It was finally achieved through an unikely alliance ofliberals and Freemasons, and conservative creolesappalled by the threat of reforms introduced by the new Spanishovernment in 1820, after the tyrannical Ferdinand VII had been·orced to abdicate, 'to save traditional New Spain from radicalpain'. The creole Agustin de Iturbide entered Mexico City inriumph at the head of the army of the 'three guarantees' (union, religion, independence) in September 1821 [Pl. 1.23], and finally suceeded in being crowned emperor, having first appealed to Ferdinand VII to accept the crown. Although Iturbide's 'Plan de Iguala',21/1. 22 Jose M arfa Espinosa, Porrmit of Bo/(11ar, pen cildrawi ng fro m life, Collection Alfredo Boulton , CaracaJ,1. 21 Jose Gil de Castro , Portrait of Simon BoU11ar in Lima,1825, oil on canvas, 210x130 cm., Sa16n Elfptico delCongreso Nacional, Ministerio de Relaciones Jnteriores,Venezuela.1.23 Anonymous, Ag,.,sffn de Iturbide proclaim ed Emp erorof Mexico on the morning of 19 May 1822, 1822, watercolouron silk, 46x60cm ., Museo Nacional de Historia, M exicoCity (INA H) .Iii,,s;-

INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROES1. 24 Juan O'Gorman, Por/l'ait of Miguel Hidalgo (studyfor the m ural in Chapultepec C as tle), n .d. , charcoal onpaper, 99x73 cm ., Collection Kristina and ErnstSchennen, Bad Homburg.1.25 Anonymous, Po,·trait of the Liberator Agust(n deItu rbide, 1822, oil on canvas, 198x125cm., Museo N acionalde Arte, Mexico C ity (!NBA) .1.26 Claudio Linati, 'Miguel Hidalgo ' , fro m Costumescivils, rnilita fres et religieux du M exique (Brussels, 1828) , TheBoard of T rustees of the Victoria and Albert Museu

1.12 Anonymous, Virgi11 of the Hill , before 1720, oil on canvas, Casa Nacional de Moneda, Poto f. INDEPENDENCE AND ITS HEROES Paintings of the Virgin in Peru and Bolivia, which often include a portrait of the donor, share with these a remarkable elaboration of decorative detail, especially in the clothes, often embroidered in fine gilt.