Transcription

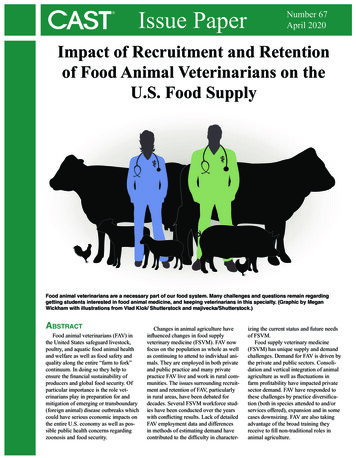

Issue PaperNumber 67April 2020Impact of Recruitment and Retentionof Food Animal Veterinarians on theU.S. Food SupplyFood animal veterinarians are a necessary part of our food system. Many challenges and questions remain regardinggetting students interested in food animal medicine, and keeping veterinarians in this specialty. (Graphic by MeganWickham with illustrations from Vlad Klok/ Shutterstock and majivecka/Shutterstock.)AbstractFood animal veterinarians (FAV) inthe United States safeguard livestock,poultry, and aquatic food animal healthand welfare as well as food safety andquality along the entire “farm to fork”continuum. In doing so they help toensure the financial sustainability ofproducers and global food security. Ofparticular importance is the role veterinarians play in preparation for andmitigation of emerging or transboundary(foreign animal) disease outbreaks whichcould have serious economic impacts onthe entire U.S. economy as well as possible public health concerns regardingzoonosis and food security.Changes in animal agriculture haveinfluenced changes in food supplyveterinary medicine (FSVM). FAV nowfocus on the population as whole as wellas continuing to attend to individual animals. They are employed in both privateand public practice and many privatepractice FAV live and work in rural communities. The issues surrounding recruitment and retention of FAV, particularlyin rural areas, have been debated fordecades. Several FSVM workforce studies have been conducted over the yearswith conflicting results. Lack of detailedFAV employment data and differencesin methods of estimating demand havecontributed to the difficulty in character-izing the current status and future needsof FSVM.Food supply veterinary medicine(FSVM) has unique supply and demandchallenges. Demand for FAV is driven bythe private and public sectors. Consolidation and vertical integration of animalagriculture as well as fluctuations infarm profitability have impacted privatesector demand. FAV have responded tothese challenges by practice diversification (both in species attended to and/orservices offered), expansion and in somecases downsizing. FAV are also takingadvantage of the broad training theyreceive to fill non-traditional roles inanimal agriculture.

CAST Issue Paper 67 Task Force MembersAuthorsDr. Christine Navarre, Chair, Schoolof Animal Sciences, Louisiana StateUniversity Agricultural Center, BatonRouge, LADr. Angela Daniels, Texas AnimalHealth Commission, Austin, TXDr. Michael O. Johnston, Social andBehavioral Sciences Division, WilliamPenn University, Oskaloosa, IADr. Clay Mathis, King Ranch Institute for Ranch Management, TexasA&M University–Kingsville,Kingsville, TXDr. Tye Perrett, Feedlot HealthManagement Services, Okotoks, AB,CanadaDr. Dan Posey, Texas A&M Veterinary Education, Research & Outreach,West Texas A&M University, Canyon,TXPublic sector demand is complicatedby questions of societal perceptions ofneed balanced with government funding challenges. A rise in the popularityof non-commercial or “backyard” foodanimals puts further pressure on publichealth and brings a need for involvementof non-FAV in FSVM.Supply of FAV is influenced by bothrecruitment and retention factors, manyof which are overlapping. One of largestbarriers to recruitment and retention of allveterinarians is student debt. The educational debt accumulated during veterinaryschool to starting salary ratio is abovewhat is considered acceptable. Solutionsto high student debt have largely focusedon mitigating it after the fact via loanforgiveness programs, in particular forFAV entering underserved rural practiceareas. The largest of these is the federalVeterinary Medical Loan RepaymentProgram (VMLRP). The long-term effectiveness of these types of programs inother professions is debatable. The shortterm retention for the VMLRP is high butlong-term retention not known.2Dr. Alejandro Ramirez, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University,Ames, IADr. Anjel Stough-Hunter, Departmentof Sociology, Ohio Dominican University, Columbus, OHDr. Carie Telgen, Battenkill VeterinaryBovine, PC, Greenwich, NYDr. David Welch, American Associationof Bovine Practitioners, Ashland, OHDr. Nicole Olynk Widmar, Departmentof Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, West Lafayette, INContributorDr. Matthew Salois, American Veterinary Medical Association, Schaumburg,ILReviewersMedical Diagnostic Laboratory,College Station, TXDr. Corrie Brown, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia,Athens, GADr. Ron DeHaven, Principal,DeHaven Veterinary Solutions, LLC,El Dorado Hills, CADr. Gregory Parham, AssistantSecretary of Agriculture and Administrator, Animal and Plant HealthInspection Service (Retired),U. S. Department of Agriculture,Washington, D.C.CAST LiaisonsDr. Gabe Middleton, Orrville Veterinary Clinic, Orrville, OHDr. Jason Nickell, Merck AnimalHealth, De Soto, KSDr. Bruce Akey, Texas A&M VeterinaryChallenges of rural life such as lack ofsocial and cultural opportunities, lack ofaccess to jobs for spouses, and childcareare of particular concern for recruitmentand retention of FAV in rural communities. This is compounded by rural practices’ attributes such as long workdaysand high on-call demands. The complexnature of these issues requires multifaceted solutions. Prior ties to the communityare key factors in retention of physiciansand physician’s assistants to rural communities. Recruiting potential studentsfrom geographical areas of need could bea priority in efforts to facilitate studentsreturning to their geographical regions ofpreference as FAV professionals.Based on limited data, it appears thatthe demographics of FAV are differentfrom veterinarians in general (older,male, less diversity of race and ethnicity). The reasons for this are not knownbut will be important to elucidate to helpdirect future recruitment and retentionsefforts.Certain practice attributes such ascaseload, facilities, and practice atmo-COUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYsphere and availability of mentorship areparticularly important to retention. Betterutilization of veterinary technicians/nurses, telehealth, business and humanresource skills can enhance both thefinancial and social qualities of a practiceand improve recruitment and retention.Recruitment and retention of publicpractice FAV is also important. Lack ofawareness of how veterinarians contribute to public health is a deterrent to FAVentering these fields. Adequate funding tosupport the training and hiring of FAV inpublic health fields is also important.Finally, robust training is needed forFAV to remain relevant to and meet thedemands of animal agriculture. Trainingalso fosters competence and employability, which are important to recruitmentand retention.IntroductionThe predicted continued growth of theworld population and subsequent globalfood insecurity is a looming threat tohuman health. Access to affordable and

safe animal source foods will play a rolein mitigation of this problem (Henchionet al. 2017; Nelson et al. 2010). Foodanimal veterinarians (FAV) safeguard thehealth and welfare of livestock, poultry,and aquatic food animals and food safetyand quality along the entire “farm tofork” continuum. In doing so they helpto ensure the financial sustainability ofproducers and worldwide food security(Alders et al 2017; NRC 2013). FAV aretrained in multispecies comparative medicine and as a result can provide a linkbetween agriculture and human medicineand advance One Health initiatives.Of particular importance is the roleveterinarians play in preparation for andmitigation of disease outbreaks including emerging and transboundary (foreignanimal) disease outbreaks. An outbreakof a highly contagious transboundarydisease in the United States is expectedto cause severe economic consequences.A 2015 study estimated that the totaleconomic impact of an outbreak of thetransboundary disease foot-and-mouthdisease in the United States would rangefrom 16 to 140 billion. Much of thisis from direct impact to agriculturalcommunities, food production, domesticdemand, international trade, and tourism(Pendell et al. 2015). Indirect impacts forwhich the economic toll are difficult tomeasure include loss of consumer trustand confidence in the food supply, andperhaps even loss of faith in government agencies entrusted with food safety.Social and psychological impacts fromlivestock producers and veterinarianslosing their livelihoods and dealing withmass euthanasia would also be expected(Govindaraj et al. 2017; O’Rourke 2003;Peck 2005; Pendell et al. 2015).Animal agriculture is constantlychanging. Consolidation and vertical integration, globalization of the food supplyand food safety systems, technologicaladvances, emerging disease and bioterrorism threats, environmental pressures,and consumerism have and will continueto reshape animal agriculture (Barringtonand Allen 2010; Delgado et al. 2001;Hoblet, Maccabe, and Heider 2003;NRC 2013; Prince, Andrus, and Gwinner2006).The veterinary needs of animal agriculture have changed as the structure ofanimal agriculture has changed. Foodsupply veterinary medicine (FSVM) hasevolved from an almost exclusive focuson individual animals as recently as the1950s to modern practice which also fo-cuses on the population as a whole (Barrington and Allen 2010). FAV currentlyserve animal agriculture via a variety ofemployment avenues in private and public practice (industry, government, andacademia) (Table 1) (White et al. 2010).The species of food animal as well asthe segment of the industry that each FAVserves varies from a narrow focus (e.g.,feedlot veterinarians) to any number ofcombinations. Poultry veterinarians workalmost exclusively for companies thatgrow and market poultry, whereas beef,dairy, and small ruminant veterinarianswork almost predominantly for privateveterinary practices. Swine veterinarianswork for a mixture of private practice andindustry.Many private practice FAV live andwork in rural communities where foodanimals are raised. Veterinarians in ruralpractice may be exclusively full-timeFAV, or mixed FAV and companionanimal practitioners. The food animalportion of mixed animal practices areincreasingly limited to cattle, especiallythe cow-calf segment of the beef industry(NRC 2013).The veterinary profession has struggled with a central workforce relatedquestion—why is it difficult to recruitTable 1. Food animal veterinarian practice types.Type of PracticeSub TypesIntegrated ActivitiesPrivate Practice§§ FSVM exclusiveúú Aquacultureúú Beefúú Dairyúú Poultryúú Small Ruminantúú Swine§§ Mixed species FSVM§§ Mixed FSVM and companion animalIndustry§§ Pharmaceutical§§ Nutrition§§ Diagnostic testingGovernment§§ USDA§§ State Animal Health Agencies§§ FDA§§ CDC§§ Homeland Security§§ Diagnostic LaboratoriesAcademia§§ Education§§ Research§§ Extension§§ Clinical diagnosis, treatment, and controlof disease§§ Herd investigation of disease andsuboptimal animal performance§§ Control and prevention of infectious andzoonotic diseases§§ Animal identification, records, and recordsanalysis§§ Integration of animal handling, nutrition,genetics, housing, and environmentalfactors into animal health programs§§ Producer education§§ On farm food safety and animal welfareprograms and audits§§ Food safety§§ Foreign animal disease preparednessand response§§ Education, Research, Extension§§ Epidemiology and disease ecologyespecially in population medicine§§ Policy and regulation formulation andimplementationCOUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY3

Why is it so Difficult to Recruit and Retain Food Animal Veterinarians in the United States?PopulationUrbanizationFood DemandoLand Available forFood ProductionoMeat PriceoFood AnimalProductionProfitabilityFood AnimalProduction IntensityPercentageVeterinary Students withFood Animal ExperiencePercentageVeterinary Students withFood Animal Medicine InterestDemand for FAVsoPerceived Ability of theUnited States to Respond to aFood Animal Disease OutbreakProfit Potential ofRural Mixed PracticeFAVsVeterinary SchoolFaculty Expertise inFood AnimalMedicineProfit Potential ofSpecialized FAVsFacultyExpertiseViciousCycleFAV WagesCost to CompleteVeterinary SchoolVeterinary StudentLoan Debt# Competent FAVsDepth of Food AnimalMedicine Training in VetSchoolRecruitmentand/or Retention of FAVin the United StatesoCurriculumShiftViciousCycleoNeed for Early CareerIncome to Service DebtRural LivingAcceptabilityAccess toServicesoVeterinary SchoolCurriculum Focus onCompanion AnimalMedicineSocial SupportSystemsEmploymentOpportunity forFamily MembersFigure 1. Causal Loop Diagram of factors influencing the recruitment and retention of food animal veterinarians (FAV) in theU.S. (O opposite relationship; i.e., an increase in one variable causes a decrease in the subsequent variable).4COUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

and retain FAV in the United States? Thisissue paper will address the many factorswhich impact recruitment and retentionof FAV. The interactive relationship ofthese factors is summarized in a causalloop diagram (Figure 1).Underlying factors impacting recruitment and retention of FAV include fooddemand and food animal productionintensity, both of which are driven, inpart, by population growth. Populationgrowth is paralleled by urbanization,which reduces land available for foodproduction and necessitates an increasein production intensity to feed a growing global population. These changesinfluence demand for and wages of FAVas well as the specialization and trainingneeds of FAV (Dicks et al. 2016). If FAVwages increase, the ability to recruit andretain FAV in the United States could bepositively impacted. On the other hand,with increasing production intensity,the percentage of veterinary studentswith food animal experience and interest could decline, impacting supply ofFAV. Shifting focus of veterinary schoolcurriculums away from FSVM does notallow for recruitment and creates a voidin training of FAV. This lack of trainingnot only impacts the ability of FAV toserve private practice and public healthneeds, but impacts training of futureFAV faculty, creating a vicious cycle thatfurther erodes FSVM curriculums.The availability of FAV in rural areashas been a particular point of discussionwhich extends to livestock producers, rural communities, and veterinary colleges,even reaching national news media andwarning of risks to livestock and the foodsupply (Honig 2018). So widely recognized are the economic, social, community, and health/safety risks of a lack ofFAV that public funding and grants haveevolved to attempt to mitigate these risksby incentivizing practitioners into ruralareas (Carrozza 2018).Often discussed from a supply perspective are the drivers of why, or whynot, individuals may choose to practiceveterinary medicine in rural areas of thecountry. Multiple social and economicfactors can be identified in driving the recruitment and retention of rural veterinarians (both FAV and companion animal),including comparative wage rates, life-style preferences, social and communitysupport systems, access to services (e.g.,childcare, schooling, and employmentopportunities for spouses), and veterinarypractice infrastructure.Demand for veterinary services in rural areas is much less often discussed butcannot be ignored. The demand influences on FSVM are numerous and interrelated, and many are out of the control of thelivestock industry and veterinarians (e.g.,consolidation and vertical integration ofanimal agriculture) (U.S. Dairy ExportCouncil 2019; U.S. Meat Export Federation 2019). The rural nature of many ofthe FAV practices is a disincentive forveterinarians that seek greater access toservices, employment opportunities forfamily members, and a more robust socialsupport system than many smaller communities can provide. Salaries for ruralmixed practices are generally lower thanfor specialized, exclusive FAV, and companion animal veterinarians and whenadded to a very high student debt loadposes further challenges for rural mixedFAV (AVMA 2019a).FAV WorkforceStudiesIn an economics framework both thesupply and demand for FAV are importantto the functionality of the FSVM marketplace. However, quantifying the supplyand demand in order to predict futureneeds of the profession so that resourcescan be properly allocated has provenchallenging. Previous FAV workforcestudies have shown conflicting results.(Brown and Silverman 1999; Dicks 2013;Little 1978; NRC 2013; PNVEP 1988;Prince, Andrus and Gwinner 2006; Tacket al. 2018; Wise and Kushman 1985).For example, a study from 1999 predictedan increase in supply and decrease indemand while a study a few years laterin 2006 predicted the opposite (Brownand Silverman 1999; Prince, Andrus, andGwinner 2006). Changes in supply anddemand could have occurred in this timeperiod but different methodology andbeginning assumptions may also accountfor some of the discrepancies (Loyd andSmith 2000). Supply and demand studiesthat focus on low market salaries andthe need for tuition subsidies and publicfunding may perceive a surplus of FAVwhile studies that focus on unmet societalneeds may see a deficit of FAV. (Wang,Hennessy, and O’Connor 2010).Accurate employment data are neededto project supply. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA)membership database is often used toquantify the supply of FAV in the UnitedStates. This database is quite robust inthat it represents 82% of the veterinarians in the United States and has moredescriptive data on employment typethan other sources of profession-widestatistics. (AVMA 2019b, c). However,20% of veterinarians do not declare theirpractice type and, for those that do, theself-declaration may be years old and nolonger accurate. Also, some practice typecategories, especially public practice caninclude both FAV and non-FAV. Datafrom organizations specifically representing FAV or public practice veterinarianswould be helpful but are not readilyavailable.On the demand side, the United StatesDepartment of Agriculture (USDA)census of county livestock numbers areoften used. One assumption made whenapplying these data is that larger livestockdensities equate to the need for moreveterinary services. But identifying thetrue “demand” for veterinary services iscomplicated. Is demand driven by thetotal number of head, number of farmswithout adjustment for farm size, oradjusted for management intensity and/ortotal animal units?Two studies have attempted tocompare databases and methods usedto predict FAV workforce needs. Wangand colleagues (2012) found that the twomethods they compared were in agreement and counties with fewer FAV, morelivestock, further from a veterinary college and more rural (defined by a ruralityindex) were designated shortage areas.In contrast, Tack and colleagues (2018)compared three different methods toidentify FAV shortage areas. In total, 728counties were identified as shortage areasamong the three methods. However, only47 counties were identified by at leasttwo methods and only one county wasidentified by all three methods as havinga shortage area.COUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY5

FAV workforce studies are alsofraught with confusing terminology. Thedefinition of a FAV is not consistent andmay account for conflicting results (Villereal et al. 2010). The terms “food animalveterinarian,” “food supply veterinarian,”“large animal veterinarian,” and “ruralveterinarian” are often used interchangeably but have different meanings to different people and groups. FAV employedin public practice are often neglected inthese studies and while their numbers arecomparatively small, they have very important roles in FSVM (AVMA 2019b, c).Another term used frequently in FAVworkforce discussions that has differentmeanings for different stakeholders is“shortage.” The term “shortage” is oftenequated with “lack of supply of veterinarians” implying that training more FAVwill fix the problem. There may be a lackof veterinarians working in food production—especially in rural areas—butif there is insufficient demand to makeveterinary practices in these areas financially sustainable or the rural communityis not attractive to veterinarians, thenthese areas will have difficulty recruiting and retaining FAV. As noted by theNational Academy of Sciences report in2013: “Regions that formerly supported aveterinarian can no longer do so. This isnot a sign of a shortfall in the supply ofveterinarians but rather of a shortfall inemployment opportunities (AVMA 2013).What are frequently termed “shortage”areas in rural communities—implyinga lack of available veterinarians to fillthe jobs—are really underservedareas” (NRC 2013).This brief history of FAV workforcestudies points out the need for development of more objective measures ofdemand for FAV and early warning indicators of imbalances between supply anddemand (AVMA 2013). This will provideguidance on how to address the needs tobetter use resources, and avoid trainingtoo few or too many FAV for the demand.Drivers of DemandPrivate PracticeThe majority of FAV are in privatepractice (AVMA 2019b, c). True demandfor FAV in the private sector is less oftendiscussed than supply issues. Fluctuations6in farm profitability, and in particular prolonged periods of financial stress, createunstable demand for veterinary services.Arguably, fluctuations in demand forveterinary (or other) medical servicesexist in all marketplaces/geographies.However, in rural areas where demand isdependent on a few large producers and/or originates largely from farming onespecies, (e.g., pork producers in Iowaor dairy producers in Wisconsin) thefinancial stresses are even more acutelyfelt by their service providers, includingveterinarians.U.S. livestock markets remain cyclicaland volatile, impacted by feed prices,labor/wage rates, land prices, capitalmarkets, export markets, and variousother business factors. (U.S. Meat ExportFederation 2019; U.S. Dairy ExportCouncil 2019). Recent disruptions to keymarkets due to ongoing trade wars anddisruptions to trading have introducedfurther uncertainty (USDA 2019).The concentration of livestock production in specific regions, coupled withfinancial challenges, introduce the potential that input suppliers—including veterinarians—face uncertainties in demandsfor their services. While concentrationof livestock operations yield changesin market structure and the demand forveterinary services (i.e., larger farms having on-staff veterinarians), financial stressof an entire production system offers thepotential to shift the demand curve forveterinary services entirely if farms exita geography. The dairy industry, for example, has faced recent extended periodsof financial stress, marked by tighteningmargins with farms facing shortfalls incash flow to meet financial obligations.This has resulted in many dairy farmsgoing out of business and poses futuresustainability problems for supportingbusinesses including veterinary practices(Program on Dairy Markets and Policy2019; Wokatsch 2018). FAV participatingin the American Association of BovinePractitioners (AABP) veterinary practiceanalysis workshops in the spring of 2019reported that the recent downturn in thedairy industry has affected their practices.Practices are responding by increasingallocation of resources for companionanimal services, the addition of new services (including consultation) related toCOUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYthe dairy industry, and in a few cases thereduction in staff size (Welch, D. 2019.Personal communication).In the long run, all inputs are variable.In the short run, fixed costs must be considered, and in particular for early careerveterinarians, the added uncertainty aboutdemand for services may add to the challenges of building practices and careersin rural areas—and dependent on increasingly volatile livestock markets. In thisuncertain climate, FAV must continue toremain relevant or risk losing their presence in animal agriculture (Chenowith1996; Getz 2012; NRC 2013; Prince,Andrus, and Gwinner 2006)."Opportunities for FAV to remainrelevant do exist, even in highlyvertically integrated segments ofanimal agriculture such as thepoultry industry. Poultry companiesfor example must manage complexand interrelated issues such as foodsafety and quality, animal welfare,and compliance with environmentaland trade regulations. The broadtraining of veterinarians makesthem uniquely qualified to addressthese issues, which opens up nontraditional job opportunities."(Glisson and Hofacre 2006)Public PracticeThere is an unquestionable needfor FAV in public practice, particularlygovernment practice, for disease surveillance, food safety, etc. (NRC 2013;Prince, Andrus and Gwinner 2006). Froma demand perspective, there may be aneed for public practice FAV, but theimpetus and funds to increase FAV capacity may be lacking. A common thread inveterinary workforce studies discussedpreviously is the balance between marketpressures—what consumers of veterinaryservices are willing to pay and societalneeds—what is typically paid by government (Dicks 2013; JCVE 1964; Little1978; NRC 1982; Wise and Kushman1985). Dicks (2013) explains:“The literature clearly definesthe need for an expanded role forveterinarians in the areas of publichealth and related sectors butoffers no measure of the willingnessto pay for the needed services byspecific public or private entities.”

The value of FAV to the private animalagriculture sectors and society are different but overlapping. What a farmeris willing to pay for (driven by farmeconomics) and what is socially optimal(e.g., transboundary disease detection)are not necessarily the same.The number of public practice veterinarians as a whole appears to be stableor increasing, but the trends in specific subcategories (industry, academia,government) are different. Uniformedservices make up the majority of newveterinarians entering public practice buttheir numbers have declined over the pastdecade (AVMA 2019c).There are other non-traditional, publichealth roles arising that need to be filledby veterinarians. The number of noncommercial or “backyard” food animals,especially poultry, is increasing in urbanand peri-urban areas. This poses zoonoticdisease and food safety risks to peopleand animal disease risks to commerciallivestock and poultry industries. Themajority of urban and peri-urban veterinarians are likely focused on companionanimals and may be unfamiliar with themedical and welfare needs of food animals as well as regulations and legalitiesassociated with treating animals designated by the Food and Drug Administrationas food producing animals. They mayalso not operate optimally as the first lineof defense for recognizing transboundarydisease in “backyard” food animals thatare a risk to commercial animal agriculture (Pires et al. 2019; Wang, Hennessy,and O’Conner 2010).Drivers of SupplyAssuming that sufficient demand forFAV exists, several questions about anample, well-trained labor supply arise.If veterinarians do not enter and remainin FSVM jobs, then government, nongovernmental organizations, industry, andagribusiness will employ non-veterinarians to fill their needs (Hoblet, Maccabe,and Heider 2003). Multiple social andeconomic factors can be identified as impacting the supply of FAV. Characterizingthese factors is confounded by the diversenature of FAV as described in the introduction. According to Walker (2009), this“identity crisis” dilutes and complicatesattempts to characterize the problemsand fill voids. Veterinary colleges, forexample, are trying to recruit and trainstudents to fill a need that is not clearlydefined. Most of the discussion of thesupply of FAV surrounds recruitment andretention of FAV to rural communities.Recruitment and RetentionAn adequate supply of FAV startswith getting students interested in FSVM(either before or after acceptance intoveterinary college), getting them adequately trained and employed in FSVMjobs, and finally, keeping them in thoseFSVM jobs. Many of the recruitmentfactors such as student debt, rural living,gender, and generation influences are alsoretention factors that lead to career orjob switching by FAV. There are others,specifically certain practice attributes (application of business and human resourcebest practices), which are especiallyimportant to retention.Nationally, career switching (starting out with one interest and switchingto another) during veterinary school islow but when it happens, either towardsor away from FSVM, it is due to exposure to new fields in veterinary schoolcoursework (Andrus, Gwinner and Prince2006; Saltman et al. 2004). Havingstrong FSVM curriculum and strong FAVfaculty and practitioner role models toattract new students to FSVM and retainthose already interested in FSVM mightbe effective.The magnitude of career switching inFAV after graduation is debatable. Somereports indicate that fewer than 30% ofthose who entered FSVM at graduation remained in FSVM practice by fiveyears’ post-graduation; (Lissmore andStowe 1989; Osborne 2003; Radostits2004; Schmitz et al. 2007). More recentlyhowever, Andrus, Gwinner, and Prince(2006) reported that career switching wasuncommon in both early and late careerFAV and report high career satisfactioncompared to other areas of the profession.The minority that did switch had lowerjob satisfaction and switched becausethey wanted more life-work balance andmore social activities.Student DebtHigh student debt is arguably the big-gest issue facing the veterinary profession. When asked about issues importantto the veterinary profession, veterinarystudents as a whole—and FAV interestedstudents in particular—ranked debt highest (Prince, Andrus, and Gwinner 2006;Volk et al. 2018). In the 2018 MerckAnimal Health Wellbeing Study, studentdebt was strongly associated with lowerlevels of wellbeing. Wellbeing decreasedas student debt increased and there wa

COUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. 3. safe animal source foods will play a role . in mitigation of this problem (Henchion et al. 2017; Nelson et al. 2010). Food animal veterinarians (FAV) safeguard the health and welfare of livestock, poultry, and aquatic food animals and food safety and quality along the entire "farm to fork .