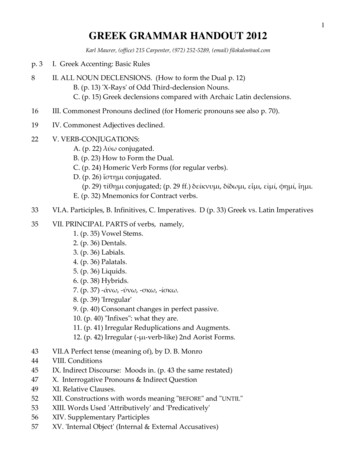

Transcription

TheologySCHOOL OFLibraryTHEOLOGYAT CLAREMONTCalifornia

he cde aeseer Na7oe eeat

BY THE SAME TICNEWTESTAMENTTHEGIFTGREATTHEGOSPELSTHEBOOKOFOF ESTAMENTBOOKEVERWRITTENACTS

Greek Culture and theGreek TestamentA Plea for the Study of the Greek Classicsand the Greek New TestamentByDOREMUS A. HAYESChair of New Testament Interpretation,Graduate School of Theology,Evanston, IllinoisBi, ue)7itiw9THE ABINGDON PRESSNEW YORKCINCINNATI

Copyright, 1925, byDOREMUS A. HAYESAll rights reserved, including that of translation into foreignlanguages, including the ScandinavianPrintedin the UnitedStates of America

RCHTEACHER,LOYALTESTAMENTFIELDPTHODIStTawd:ayA ;SMVEOINDSID334680

CONTENTSA PrerRsonaAL FOREWORD.9PART‘A WONDERFUL)LAND)sefh csilII.A WoNDERFULPEOPLE.19III.A WoNDERFULLANGUAGE.66IV.A WonbDERFULLITERATURE.110A WonperRFUL Boox.Tue GREATESTGREEK Book: THE New TESTAMENT152

A PERSONALFOREWORDFor some years early in life I held the chairof Greek Language and Literature in a collegefaculty. For many years now I have workedin the department of New Testament Interpretation in a theological school. All of myteaching career has been devoted to a study ofthe Greek, and my life has been indefinitely enriched thereby. This little book is written inthe hope that others may be induced to sharein the privileges I have enjoyed.I hear to-day that one of my neighbors hasbegun the study of Greek in a correspondencecourse. Years ago she heard Professor Gildersleeve lecture on the advantages of Greek culture and ever since she has longed to studyGreek for herself. She had no opportunity inmiddle life; but now in her widowhood andthe comparative leisure of advancing years sheis realizing her cherished ambition at last.She is at present reading the Anabasis withgreat delight and we can imagine what herjoy will be when she comes to the reading ofher Greek New Testament.Within the week I have heard of another of9

10A PERSONALFOREWORDmy neighbors who when sent to Arizona in illhealth was warned by his physicians not totake many books with him; and so he took onlyone book, his Greek Testament. Will anyonewho reads this volume be disposed to questionthe wisdom of his choice?I desired to call this book Gold and WhiteIvory, taking the words from one of Pindar’s‘Odes to represent what was valuable and to‘be had only for effort and cost; but the publishers thought that the title was too blind,and they preferred the prosier and plainer onenow given. One must dig for gold. One musttravel far to find original ivory.Yet thereare those who think it worth while and whocome home laden with rich treasure. “Are therenot many, both among the laity and the clergy,who will be willing to toil as much as may benecessary in order to enjoy the reward of personal and first-hand acquaintance with GreekCulture and the Greek Testament?Whenthey once realize its value and its necessity,I am assured that they will.in that faith and to that end.cae June 1, 1925.I have written

PARTIA WONDERFULLAND1. Tue land of the Greeks was and is a mostremarkable land.Its most noteworthy feature is its remarkable coast line. No otherland has anything like it. The continent ofAfrica is an almost solid mass, presenting anunbroken front to the sea. Africa prefers tosit out on desert sands and sun herself. Sheis the Dark Continent; and her people areblack.It is small wonder; she hates the waterso. Africa has but one mile of coast line forevery six hundred and twenty-three squaremiles of surface. On the other hand the continent of Europe loves the sea. She runs outin great peninsulas to meet it, and hugs it toher in great gulfs. She has one mile of coastline for every one hundred and fifty-six squaremiles of surface.“As the configuration of Europe contrastswith that of Africa, the configuration ofGreece contrasts with and surpasses in itscomplexity even that of Europe. The coast ofGreece is a continuous succession of bays,11

12GREEKCULTUREANDpressing in upon the land at every possiblepoint from the east and the west and the south.Everywhere peninsulas run out into the sea;everywhere the sea thrusts itself in betweenthese projecting points of land. Half the sizeof Portugal, Greece has a coast line greaterthan Spain and Portugal together.”! Greeceproper is smaller than the State of Pennsylvania, but “its coast line is almost as long asthe whole Atlantic seaboard of the UnitedStates from Maine to Florida.” The sea is onevery side of the land and in every part of theland. There is not a foot of land in Greecewhich is more than forty miles from the sea.2. Another noteworthy feature of the landis to be found in the multitude of its mountains. No land is richer in mountain peaks.Nearly nine tenths of its surface is coveredwith mountain ranges.There is no spot inthe land which is more than ten miles awayfrom the hills. Along the major part of ourAtlantic coast, while we have the ocean, themountains are a long way off. In Coloradoand Wyoming we have the Rocky Mountains,but the sea is far, far away. In the great flatcountry of the central valley and the desert‘Hayes, Paul and His Epistles, p. 189."Greene, The Achievement of Greece, p. 15.University Press. Used by permission.Harvard

THE GREEKTESTAMENT13and the prairies life may become flat and monotonous too.California is the one greatState of our Union which has both the mountains and the sea. It does not compare withGreece in this respect, but in many places youcan be within sight of salt water and at thesame time within sight of lofty mountainpeaks.The white-capped breakers and thesnow-capped summits keep the air vital all thetime. Greece is the ideal land in this respect.It has more mountains and more sea to theSquare mile than any other land on the globe.Not even Japan can compare with it.3. A third noteworthy and peculiar featureof the land is to be found in its climate. Mountains and sea are in close proximity in thefiords of Norway and in the volcanic regionsof the South Seas; but no one would think ofthese as ideal homes for the human race.Greece, like every mountainous country in thesouth, has every variety of climate representedin the various zones of mountain height; butmore than most other countries it has a remarkable variety of climate in its valleys andon its level plains. Gell says that in travelingthrough the Morea in March he found summerin Messenia, spring in Laconia, and winter inArcadia, inside a radius of fifty miles; andCurtius tells us that within a boundary of not

14GREEKCULTUREANDmore than two degrees of latitude, the land ofGreece reaches from the beeches of Pindusinto the climate of the palm; and on the entireknown surface of the globe there is no otherregion in which the different zones of climateand flora meet one another in so rapid a succession.?The land of the Greeks was a land of sunshine, full of sweetness and light. On thewhole the climate tended to cheerfulness andwas a constant stimulus to the cultivation ofall the civilized arts. At Athens, after observations extending over twenty-four years,the director of the Observatory there reportsthat there are on the average in the year onehundred and seventy-nine clear days, on whichthe sun is not hid for a moment, one hundredand fifty-seven days which are bright days,on which the sun is hid perhaps for half anhour, twenty-six cloudy days, and only threedays in which the sun is not seen at all.Neumann and Partsch* tell us that the average number of sunny days in Germany is Seventy-nine in the year; seventy-nine days ofsunshine as against three hundred and thirty-six in Athens!With the fogs of England andthe mists of Scotland it is not likely that they Curtius, History of Greece, vol. i, p. 11.*Physikalisch Geographie von Griechenland,p. 24.

THE GREEKTESTAMENT15would make a better showing than Germanyin this regard, and other European countrieswould be more or less like them; and we arenot surprised that Herodotus, who was a greattraveler in Asia and Africa, came to the conclusion that beyond all other countries in theworld Greece had the most happily temperedseasons, and that other good authorities likeAristotle and Hippocrates agreed with him.One needs only to visit Greece, and then goon to Palestine and Egypt to-day, to sympathize fully with their verdict in that matter.Aristotle was the closest observer of his ageand a man of encyclopedic information, andhe averred that the peoples in the colder regions of Europe in his day were energetic butlacking in intelligence and artistic skill, whiletheAsiaticswereintelligentandartisticenough but they were wanting in the energythat characterized the inhabitants of a colderclime; but the Greeks, living geographicallybetween the two, had the energy of the oneand the intelligence and artistry of the other.It is true that their land had the ideal climatefor study and work. The energies of its people “were neither lethargized by excessive heatnorparalyzedby excessive5Makers of Hellas,Used by permission.p.24.Charlescold.” Scribner’sTheirSons.

16GREEKCULTUREANDheads could be as clear as their skies all theyear round. Their mental powers were neithermelted in summer nor frozen in winter. Theirclimate did all it could for them in keepingthem in good working condition week afterweek, month after month, year after year.4, A fourth feature in the situation of thisremarkable land ought to be mentioned.Itwas the natural center of the ancient world.Reclus, the geographer, has said: “The axesof civilization in the western extremity of Asiaconverge upon the basin of the Hellenic Med-iterranean.The long fissure of the Red Seapoints directly toward the Eastern Mediterranean. The winding valley of the Nile opensin the samedirection.The PersianGulf,continued to the northwest. by the Euphrates,runs toward that angle of the Mediterraneanwhere is Cyprus. Farther north all the rivers,all the highways of commerce which descendfrom Asia Minor, from the continent of Asia,from the Sarmatian plains to the Black Sea,becometributariestotheGreekwatersthrough the Bosphorus and Hellespont.”’ Such was this land; surrounded by sunnywaters, filled with mountain fastnesses, withthe ideal climate for either pleasure or exertion, and in the focal center of the civiliza*Contemporary Review, October, 1894.

THEGREEKTESTAMENT17tions of the three great continents of the ancient world. “The southeastern extremity ofEurope, Hellas lies, as it were, between threeworlds. Opposite stretch the most fertile partsof Africa—the Egypt of ancient days, with itsmysterious religion, its curious art and learning. Nearer, across a sea studded with chainsof islands, each of which, in the infancy ofnavigation, served as a stepping-stone to themariner, lie the shores of Asia, the home of theearliest civilization.To the west, separatedonly by waters whose breadth in some placesdoes not exceed forty miles, is Italy, in theseold times the representative of unexplored regions beyond. Thus stood Hellas, between theOld World and the New—the gateway, as itwere, through which the primitive knowledgeof the East was to enter upon a fresh and morevigorous life of progress in the West.’Greece is one of the three peninsulas ofSouthern Europe.On the map the western-most, Spain, looks like a clenched fist, ready tocrush or maul its subject peoples in the Neth--erlands, in Mexico, in the Philippines, inCuba, in Peru. The middle peninsula, Italy,looks on the map like a giant foot or boot,kicking at Sicily first of all, but ready to setitself upon the neck of a conquered world."Makersof Hellas,p. 13.

18GREEKCULTUREANDThe peninsula of Greece on the map has beenlikened to a mulberry leaf or the webbed footof a duck, but these comparisons are so inadequate that we are tempted to suggest that itis more like an open palm with the fingers extending everywhither or possibly still morelike the corrugated surface of a human brain.In physical conformation it might stand onthe map for a symbol of acquisitiveness andintellectuality, of open-handedness and openmindedness, of a desire for personal possessiononly that it may impart its riches to all theworld. Spain was selfish, and died as a worldpower long ago. Rome was selfish, and itsworld empire passed into other hands. Greececontrols the life and dominatesof the world to-day.the thoughtEnvironment has something to do with thedevelopment of any people.Geographicalsituation may not account wholly for nationalcharacteristics; but under such unprecedentedly favorable conditions for the developmentof a race as were furnished by the command-ing position, the air, the soil, and the safeharbors on the many seas of Greece, we naturally would expect the development of a uniqueand wonderful people.

THE GREEKTESTAMENTPART19ITA WONDERFULPEOPLE1. Pioneers and Discoverers.We are considering the ancient Greeks in this discussion,the Greeks of the primitive and then of theclassical periods, the Greeks of the early andthen of the Great Age. The early Greeks livedupon the sea as much as upon the land. Thequiet waters of the bays tempted them fromthe shore; the outlying islands were so nearat hand that the most inexperienced marinersmight venture there; and as island upon islandrose upon the horizon they found themselvesled by easy stages to the three continents fromwhose varied products they might enrichthemselves.As Curtius says, “Searcely a single point isto be found between Asia and Europe where,in clear weather, a mariner would feel himselfleft in a solitude between sky and water; theeye reaches from island to island, and easyvoyages of a day lead from bay to bay.”?While the other Aryan peoples of Europe had4Curtius, op, cit., vol. i, p. 10.

20GREEKCULTUREANDno other name for the sea than “the barren,”“the waste,’ “the dead water,’ the Greekscalled it “the bridge” or “the pathway.” Tothem the sea was no barrier between them andother peoples.It was the highroad unitingthem to all.Almost perforce, therefore, the Greeks became mariners, world-wanderers, discoverers.Their horizon was broadened and they cameto have wider interests and a wider knowledgethan the stay-at-home peoples had. The seadid that for them. They came to be a peopleof cosmopolitan outlook and of encyclopedicinformation. They were “the world’s greatestpioneers and experimenters,” and we are assured that on the basis of their experimentsmore than half the culture of the modernworld rests. The Greeks were both mountaineers and mariners; and it has been suggestedthat their mountains helped them to be maintainers of the old and the sea made them seekers after the new. They were conservative ofthe substantial and the good, and consumedlyeager for new and better things.2. Lovers of liberty. Mountaineers alwaysare lovers of liberty. The Greeks were no exception to the rule. They always were readyto fight, bleed, and die for freedom. Patriotism and independence always were character-

THE GREEKTESTAMENT21istic of the race.In our histories Salamis,Marathon, and Thermopyle almost have become synonyms for these terms.The peopleon the plains are open to every assault, and ifoverrun by superior numbers they easily areswept into great empires; but the people inthe mountain passes are not overcome so readily. Sometimes a handful of men there canhold a whole army at bay.The mountains made of Greece a naturalfortress, shielded on the west and on the north.Shut in on every side the population of eachmountain valley had to be independent.Itwas a difficult journey to the next neighborsacross the peaks. Isolation and liberty wenttogether; and together they were cherishedand loved.To conquer such a land everymountain valley had to be mastered in succession.If one of them was left unvisited, itbecame the refuge and the rallying-place ofthe surviving friends of liberty.Patriotism is fostered most easily amongmountain peaks. What would the Swiss carefor Switzerland minus the Alps? The spiritsof the mountaineer flag upon the prairies orthe plains.He feels smotheredthere.Hepines for the ozone of the heights. He lovesto dwell: in memory upon the rocks and“templed hills.”He sings,

22GREEK CULTUREAND“My country! ’tis of thee,Sweet land of liberty,Of thee I sing:Land where my fathers died!From every mountainLet freedom ring!”sideThe Greeks were characterized equally bylove of their native land and love of liberty.They were independent in their thought andspeech and life, original in their literature,vital and varied and unrestrained in everything. They invented politics, and they perfected the conceptions of law and liberty, justice and democracy, parliament and publicopinion. They felt the need of these thingsand went to work upon their development withthe same thoroughness and genius they gaveto their literature and their art.3. Moral and Religious. Mountaineers arerigidly and ruggedly religious. To the Greeksthe gods dwelt everywhere; but the home ofZeus and the chief court of all divinities wason Mount Olympus. Greece reached outwardin all directions toward the continents andinto the sea; and Greece reached upward inher innumerable mountain peaks toward thepurer atmosphere and into the clear sky. Sothe Greeks ever were reaching outward to the

THEGREEKTESTAMENT23uttermost parts of the earth in the acquisitionof spiritual knowledge and material wealth;and they ever were reaching upward to the uttermost possibilities of human achievementand aspiration.It was a question to whichthey owed the more, the inspirations of themountains or the invitations of the sea.Their religion had in it the freedom of theopen air. There was nothing depressing aboutit. They had no religious austerities or monasteries.They never indulged in fastings orflagellations.Their religion was a naturaland a joyous one. Their faith was cheerful,facing either life or death.The Ceramicus,their cemetery, was filled with artistic monuments without a word of terror or despair inscribed upon them. Their sorrow was sincerebut serene.Excessive mourning was forbidden by law. Their faith did not fail them inthe last hour. They were not afraid of death,because their consciences were clear in life.They were a highly moral people when theirrace was at its prime. As John Fiske says,“They had an open, childlike, sunny conception of religion”; and “their moral and religious life sat easily upon them like their owngraceful garments.”?In an article on “TheMartin, Is Mankind Advancing? p. 172.mission of the author.Used by per-

24GREEKCULTUREEthical Value of Hellenism”ANDMr. Alfred W.Benn has said, “I am prepared to support thethesis that the Greeks were as great in whatbelongs to the conduct of life as they con;fessedly were in the creation of beauty or ithe search for truth. . . . The moral life ofno other people was so rich, so well-balanced.’They excelled morally and artistically.The Greeks practiced monogamy and abhorredpolygamyat the timewhenthe He-brews still were a polygamous people.Long' before Jesus had given the Golden Rule to hisadisciples, “All things therefore whatsoeverye would that men should do unto you, evenso do ye also unto them,”* Isocrates in hisNicocles had taught the Greeks not to do toothers that which would make them angry ifothers should do it to them.In the CritoSocrates concludes, “We ought not to retaliateor render evil for evil to anyone, whatever evilwe may have suffered from him,” and he manifested the same spirit and meant the samething with the Master on the Mount.Longbefore the days of Socrates, Pittacus of Mitylene had said, “Forgiveness is better than revenge,” and “Speak no evil of a friend, or*International Journal‘Matt. 7. 12.*Crito, 49C.of Ethics, April, 1902.

THE GREEK TESTAMENTeven of an enemy.’ 25No higher standards ofspeech and conduct are enunciated in our ;Gospels.Long before that young prophet of Nazarethsaid to his disciples, “Ye have heard that itwas said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth fora tooth; but I say unto you, Resist not himthat is evil,’ Lycurgus the lawgiver had illustrated the spirit of that command by his personal example.His eye was put out by anangry young man and instead of taking vengeance upon the ruffian Lycurgus took him tohis own home and there reasoned with himwith such cogency of argument and such courtesy of conduct that the young man was converted from an enemy into a friend, and weread that he became “a most decorous and disereet man.’Modern theology has not transcended themoral notions of AXschylus and his school.He censured high-handedness even in the gods.He taught the indelible nature of sin.TheGreek drama in the hands of A)schylus andSophocles and Euripides served the purposesof the modern pulpit in being the greatest ele-vating and moralizing influence in the land.sDiogenes Laertius, i, 76, 78, att. 5. 38, 39.*Plutarch, Lycurgus, xi,mn,ae

26GREEKCULTUREANDThe immorality characteristic of many performances on the modern stage never was tolerated among the Greeks.Euripides describes the conditions in cAbhenein the following words:“The weak, the rich, have here one equal right,And penury, with justice on its side,Triumphs o’er riches; this is to be free.Is there a mind that teems with noble thoughtAnd useful to the state? He speaks his thoughtAnd is illustrious. When a people freeAre sovereigns of their land, the state standsfirm.”We give much praise to the Hebrew prophets for their passionate preaching of civicrighteousness and social justice; but it is wellfor us to remember that at the very time theywere saying these things, “there were established righteous governments in Greece underwhich the poor working man could not beplundered with impunity as he was in the HolyLand. Unaided by supernatural promises orterrors, the Greek legislators, magistrates, andorators actually accomplished that for whichthe Hebrew prophets vainly strove.”To the Greek sin was ugly, but there wassomething fine in high behavior. The beautiful always appealed to him and noble conduct*Huripides, Suppliants,399f.

THE GREEKTESTAMENT27was a thing of beauty in which he rejoiced.He was moral and religious not because hewas afraid of the law of the state or the wrathof the gods but because he loved the true, thebeautiful, and the good.It was the Greekideal which Paul put before the Philippianswhen he wrote to them, “Finally, brethren,whatsoever things are true, whatsoever thingsare honorable, whatsoever things are just,whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever thingsare lovely, whatsoever things are gracious; ifthere be any virtue, and if there be any praise,think on these things.”’ The whole Epistle tothe Philippians is characterized by a graciousness of manner and a cheerfulness of spirit anda joyousness of religious faith which would beattractive to any Greek community, and thisexhortation to think upon things gracious,lovely, pure, just, honorable, and true simplyemphasized the ideals of their own philosophers and their own national life.The religious spirit of the Greek finds itsclassical expression in the prayer with whichPlato closes the Phedrus: “O beloved Panand other gods here present, grantto metobecome fair within.Let my outward posses-sions be such as are favorable to my inwardlife. May I think the wise man rich. Give me*Phil. 4. 8.RAERIaaaNSatas

28GREEK CULTUREANDso much gold as only the temperate man canbear or carry. . .O beloved Pan, grant meto become fair within.”' That sums it up;plain living, high thinking, and the beauty ofholiness within.Hippocrates, about 400 B. ., was thefounder of medical science among the Greeks,and he illustrates well the spirit of religionwhich the Greek carried into all of his work.The Hippocratic oath, taken by all the practitioners of his school, contained the followingpledges: “I will give no deadly medicine toanyone if asked, nor suggest any such counsel;nor will I aid a woman to produce abortion.With purity and holiness I will pass my lifeand practice my art.” This high ideal helpedto maintain the dignity of the medical profession among the Arabs, Jews, and. Christiansthrough all the succeeding centuries. It illustrates the religious spirit maintained by theGreeks in all their professions and arts.4. Devoted to the Ideal. Highly favored byclimatic and geographicalconditions theGreeks made the most of their opportunitiesand realized their possibilities in fuller measure than any other nation did.ProfessorButcher, in his volume, Some Aspects of ‘theGreek Genius, has summarized the character- 8Plato, Phedrus, 279B,

THE GREEKTESTAMENT29istics of the Greek people under the fourheads: (1) A love of knowledge for its ownsake, a passion for truth, and for seeing thingsas they really are, with no care for consequences.(2) A strong belief in conduct—such “noble action” as might be becoming to“clear thought.” - (3) A mastery of art, suchas still sets its models for the world—art alsobeing loved for its own sake, and its chief excellences being the absence of exaggeration,the delicate spirit of choice, the unobtrusivepropriety of diction.(4) A passionate demand and assertion of political freedom.These were the “Gifts of Greece,” which gaveher the right to the name of “The Holy Landof the Ideal.”It is a lofty title. To try to reach the idealhas seemed to the most of us to be an attemptat the impossible; and we moderns are for themost part tamely content with second-bestthings. It was not so with the Greeks. Theyconstantly were striving for the realizationof the ideal; and it may be well for us moderns, with our growing contempt for the ancients and our increasing neglect of the classicmodels and the classic times, to remember thatin Greece, in science and philosophy, in literature and art, there has been the most com-plete realization of the ideal all-around human

30GREEKCULTUREANDlife of a nation which the world as yet hasseen.Our Christian religion comes to us directlyfrom Judaism but it has been greatly modifiedfor the better by its contact with Greek influences.The humanistic elements of Hellenism were in fullest accord with the spirit ofJesus.It believed with him that God andman were much alike in their nature. It rejoiced in the beauty of the universe and thecomeliness and charm of all created things.It was broader-minded than Judaism and moreappreciative of the immanence of God and theunlimited possibilities of man.This faith inthe continual presence of God and the undefined and undefinable powers of man led theGreeks to strive for better things and to becontent with nothing but the ultimate best.Their ideal was perfection and their constantendeavor toward it made Greece at last TheHoly Land of the Ideal.This is so patently true that among thestudents of Greek antiquity, the archeologistsand philologists, the historians of their art,their literature, and their nation, the tendencyseems to be toward an enthusiastic and almostunlimited idealism. We turn from the reading of their volumes with the more or lesspositive impression that classic Greece must

THEGREEKTESTAMENT31have been blessed with an Edenic loveliness oflandscape and life.They must have hadstorms sometimes, there must have been darkdays; but for the most part we have the visionof a cloudless heaven, of a fathomless blue skyoverarching the fathomless blue of the summersea, of Olympian heights where gods mightdwell in boundless light and in perfect peace,of Arcadian vales where nymphs and faunsand dryads might find fit frolicking place.5. Beautiful in Form. This perfect beautyof sky and shore and sea was reflected in theforms of the Greek women and men; in theApollo Belvederian symmetry and strengthof the naked youths of the gymnasium, in theVenus-de-Milo grace and loveliness of thePenelopes and Aspasias and Helens, the maidsand mothers of this favored race; in the serenestateliness of the Greek warriors and artistsand lawgivers and philosophers; in the beautyof an Alcibiades, the dignity of a Pericles, thesurpassing symmetry in feature and form in afavorite poet like Sophocles; in the only lessideal figures and carriage of the great populace which formed in religious processions likethat displayed upon the matchless frieze ofthe Parthenon.We shall not soon forget the certainty ofenthusiasticconvictionwithwhichErnst

32GREEKCULTUREANDCurtius, the poet-archxologist and the greathistorian of Greece, told us in his classroomin Berlin that “ugliness was the rare exceptionamong the Greeks; they were the people ofperfect form. . . . They were freer than othermortal races from all that hinders and oppresses the motions of the mind. . Withother nations beauty, with the Greeks wantof beauty, was the startling exception to therule.” Professor Gulick, in his Life of theAncient Greeks, agrees with Professor Curtiusat this point. He says, “The Greeks produceda larger proportion of handsome men andwomen than any people who have ever lived.They were tall and well proportioned, havingfirm skin and supple muscles, well-formedheads, straight noses, and’brown hair. Aboveall, they were noted for their extraordinarilybeautiful eyes, possessing a keen and steadygaze.”’12Ridpath is as enthusiastic as either of theseauthorities we have quoted, and, if possible,he is even more so. He declares, “In beauty ofbody the Greeks were peerless; in agility andnervous vigor they were the finest whom theworld has produced.The Greek was morealive than any man of antiquity. This highly“Gulick, Life of the Ancient Greeks, p. 171.ton & Co.Used by permission.D. Apple-

THEGREEKTESTAMENT33wrought physical manhood was the foundationof his wonderful mind, of his energy, hisreason, his imagination, his courage.InGreece nature accomplished the finest motherhood of man.In the fair skin, blue eyes,beautiful body, and radiant face of the Greekyouth she held

of Greek Language and Literature in a college faculty. For many years now I have worked in the department of New Testament Inter- pretation in a theological school. All of my teaching career has been devoted to a study of the Greek, and my life has been indefinitely en- riched thereby. This little book is written in