Transcription

TOWARDSBR AIDINGElwood Jimmy and Vanessa Andreottiwith Sharon Stein 1

TOWARDSBR AIDINGElwood Jimmy and Vanessa Andreottiwith Sharon Stein

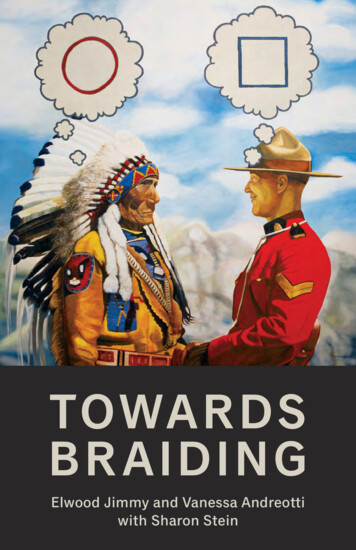

Towards BraidingElwood Jimmy and Vanessa Andreottiwith Sharon SteinThis booklet is licensed under a CreativeCommons Attribution 4.0 International license.June 2019ISBN: 978-0-9877238-9-5Cover: David Garneau, Not to Confuse Politeness with Agreement,oil on canvas, 122 x 122 cm, 2013. [Private collection]Note from the artist: This painting is based on a popular postcard from the1950s. The photographer is W.J.L. Gibbons of Calgary, and the image featuresFSC Label—FULL Version (LANDSCAPE)an unknown young Mountie and Ubi-thka Iyodage, also known as Chief SittingA minimum height of 12 mmEagle (1874–1970) and also as Johnwho washeighta prominentof theA Hunter,minimumof leader12 mmMust have an area of clear space (shown here in green) aroChiniki band of Stoney Nakoda to the heightof theofletters‘FSC’Musthavean areaclearspace (showimage to suggest some irony; I wantednot simplyborderto reproducethe image butThe surroundingis requiredequivalenttotheheightofthe lettersre-present it. The image is of an Labels“Indian”anda “representativeof the State’sareprovidedin black, white,and green.power.” I suppose the intention ingborderisinrequiredTheFSClabelstatements areavailablemultiple languagFSCLabel—FULLVersion(LANDSCAPEway to the new country, but the young man (who isn’t given a name) is k,out of his league. I repurposed the image to suggest two very different ways of white, anFSC MustLabel—FULLVersion(LANDSCAPE)have anareaof clearspaceavailable(shown hthinking and seeing the world.The FSClabelstatementsareFSC Label—FULL Version (LANDSCAequivalentminimum height12 mmof the letters ‘FSCto theofheightMustan areaofclear isspace(shown hereFSC umwidthof17mm.Labels(LANDSCAPE)are provided in black, white,‘FSC’and grFSC Label—FULL Versionsurroundingborder(shownis requiredhaveanoflabelclear statementsspacehereavailablein green) inaroA ovidedinblack,white,and greenequivalenttotheheightofthelettersMust have an area of clear space (shown here in ‘FSC’green)aroundthe lThe heto theheightofbordertheletters‘FSC’ are available in mularePitaguaryprovidedin black, white, and green.The surroundingborderis requiredInside and back coverart: LabelsBeniciolabelstatementsareavailablein multiple languagLabels areTheprovidedin black,white,andgreen.AFSCminimumwidthof17 mm.Design: Gareth Lind,LindlabelDesignThe FSCstatementsareavailableinmultipleFSC Label—FULL Version languages(PORTRAIT)FSC Label—FULL Version (PORTRAMust havean area ofof clearspace (showminimum width17 mm.FSC ALabel—FULLVersion(PORTRAIT)equivalentto widththeheightthe (shownlettershhaveanareaof clearAMustminimumof 17mm.ofspaceThis booklet was publishedwith supportfromREQUIREMENTSMusagetesFSC clearspace(shownhereA minimum width of 11mm.as part of the —FULLVersion(PORTRAIT)The raitformatLabelsareprovidedinin black,white,anA dhaveanareaofspaceherein green)TheFSClabelstatementsareavailableMust have equivalentan area ofLabelsclearspace(shownin ‘FSC’green)aroundtheTheFSClabelareavailablein ltotheheightof statementsthe herelettersareprovidedinblack,white,and greenmusagetes.caequivalentto theareheightof the‘FSC’Labelsprovidedinlettersblack,white, andTheFSClabelstatementsare green.available in mulThe surrounding border is requiredLabels are provided in black, white, and green.The FSC label statements are available in multiple languagesFSC Label—MINIMUM REQUIREMENTSFSC ALabel—MINIMUMminimum width ofREQUIREMENTS11mm.FSC Label—MINIMUMREQUIREMENA minimum width of 11mm.Can be displayed in landscape or portrait fA minimumwidth of 11mm.Musthaveantoareaclear spacehereCanbedisplayedinofheightlandscapeor portrA minimum width of 11mm.equivalenttheof the(shownletters‘FSCequivalenttoportraitthe heightof the letters ‘FSC’Can be ck,white,andgrMust Labelshave areanprovidedarea ofclearspace(showin black,white,and greenMust have an area of clear space (shown herein green)aroundthe lequivalent to the height of the lettersbehavedisplayedin landscapeor portraitform1996FSCA.Mustan areaof clear space(shownhFSC Label—MINIMUMCanREQUIREMENTS

Table of ContentsPreface. 7Bricks and Threads. 13Braiding. 21For organizationsstarting this journey. 41When things fall apart. 55Missteps on the pathto braiding. 63Towards generative braidingmanifestations. 69Reflecting forward. 85Afterword. 91Acknowledgements. 95Recommended reading list. 97

4 Towards Braiding

Table of Contents 5

Overleaf: David Garneau, Not to Confuse Politeness withAgreement, oil on canvas, 122 x 122 cm, 2013. [Private collection]

PrefaceOur story starts with things fallingapart.This is a very common story: anorganization decides it wants to “Indigenize”and/or “decolonize” and hires an Indigenousperson to do this work for them, but usually this position is notone of decision-making authority or autonomy. The Indigenousperson accepts the job, hoping that the organization understands Indigeneity and decolonization the same way they doand that they will be able to influence change. However, in timeit becomes clear that, apart from this new position, most activities of the organization go unchanged: the mere presence ofan Indigenous person is meant to Indigenize and decolonize thepublic image of the organization. Despite a genuine yearning fordeeper connections and relationships, the organization performsa socially sanctioned desire for a specific formula:business as usual non-threatening Indigenous content guilt and risk of bad press7

The Indigenous employee is expected to facilitate convenient Indigenous involvement, to exercise conditional Indigenousleadership, to curate Indigenous content that is palatable to thetaste of non-Indigenous consumers, to perform gratitude for“being included,” to embrace the opportunity for reconciliation,to offer redemption to the organization, to appear in equityphotos, and to allow the use of their presence as an alibi for thecontinuity of colonial desires and relations (see “academic Indianjob description” poem on page 24). Unrealistic expectations areput on the Indigenous employee to tackle issues in every aspectof the organization, which often amounts to the expectation thatone employee will take on multiple full-time jobs.At some point, the two sides and their differing expectations clash. The Indigenous person feels instrumentalized foran agenda that is still fundamentally colonial in an organizationthat fails to imagine that other ways of working, collaboratingand relating are possible. The Indigenous person calls out thistokenism and the frustration it brings. Next, the Indigenousperson who identified the problem starts to be perceived as aproblem and as someone who is taking advantage of the organization’s gesture of inclusion. The organization either ignores ordenies what was communicated (placing blame on the Indigenous person) or makes superficial changes without realizing thedepth and difficulty of the learning that is necessary to interruptsystemic colonial patterns that are perceived as normal, naturaland, in many cases, benevolent.When the Indigenous employee loses faith in the commitments of the organization, they also start to actively or passivelyresist the organization’s demands. In turn, the organizationstarts doubting the Indigenous person’s ability to do the job8 Towards Braiding

they were hired to do. The inability to communicate across thisdivide builds mistrust and anger on both sides. At one point theIndigenous person burns out, threatens to quit, and accusesthe organization or individuals in the organization of racism and(neo)colonialism.The organization then feels justified in their judgmentthat this Indigenous person is unstable and incompetent. TheIndigenous person quits or is fired. The organization hiresanother Indigenous person, who seems to be more amenableto performing the required set of tasks. In time, the differentexpectations clash, and the damaging and re-traumatizing cycleunfolds.This is the general story — an all too common one. However,this text is about an experiment to try and rewrite how a storylike this generally ends, in an effort to interrupt the cycle, andto see what else is possible if we approach things differently. Atthe point of breaking, we decide between two options: to let thestory play out as it usually does, or to try and be taught by theserepeated mistakes from a place of not knowing what to do. Werealize that starting from this place of not-knowing could be agenerative place from which to respond to a non-generative situation of mistrust and resentments on both sides. This requirespatience, humility, generosity and a decision on both parts totake a risk, knowing that it might not work. In this text, we reporton the first year of such an experiment, but it remains ongoing,as does our learning, and it still hasn’t (and probably won’t everbe) finished.This text is based on conversations that have happenedduring an ongoing collaborative process between Elwood Jimmyand Vanessa Andreotti as part of their work with Musagetes, afoundation with a mandate to make the arts more central andPreface 9

meaningful in peoples’ lives, in our communities and societies.This collaboration involved several modes of relational engagement with Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists, scholars, andcommunities, including visits, gatherings and consultations,addressing the following questions: What are the conditions that make possible ethical and rigorous engagement across communities in historical dissonance that can help us move together towards improvedrelationships and yet-unimaginable wiser futures, as we faceunprecedented global challenges? What are the guidelines and practices for ethical and respectful engagement with Indigenous senses and sensibilities(being, knowing, relationships, trauma, place, space andtime) that can help us to work together in holding space forthe possibility of “braiding” work? How do we learn together to enliven these guidelines with(self-)compassion, generosity, humility, flexibility, depth andrigour, and without turning our back to (or burning out with)the complexities, paradoxes, difficulties and pain of thiswork? What kind of socially engaged and community anchoredIndigenous-led arts-based program can support this processin the long term? What are the expectations in terms of responsibilities of theorganization to the place/land and her traditional ancestralcustodians from the perspectives of the local Indigenouscommunities?10 Towards Braiding

This document reflects our collaborative learning from thefirst year of this collaboration. We honour all of those who haveinspired the insights garnered thus far and thank them againfor their time and generosity in sharing their stories and wisdomwith us. We would also like to thank everyone at Musagetes formaking it possible for this process to happen.— Elwood and VanessaPreface 11

Bricks and ThreadsAnalogies for different sets of waysof knowing/beingIn this project we have tested differentframings for the distinct sensibilitiesinvolved in the highly charged context ofsettler–Indigenous relations and have foundthat a distinction between transcendenceand immanence offered a useful tool for analyses of recurrenttensions, as well as possibilities for new forms of engagement.A social cartography using the metaphor of construction bricks(transcendence) and knitting threads (immanence) proved veryuseful in engaging Indigenous artists in conversations aboutthe tensions of working in non-Indigenous institutions and theessential steps that could enable possibilities for new forms ofcollaboration. We present the distinction between bricks andthreads in this section. Like all metaphors, this one is partial andlimited, and thus we also include several caveats.Brick sense and sensibilities stand for a set of ways of beingthat emphasize individuality, fixed form and linear time; where the world is experienced through concepts thatdescribe the form of things and places them systematically inordered hierarchical structures;13

where the value of something is measured against itscapacity, achievement or potentiality to “move thingsforward”; and where self-worth is dependent on external validation.Thread sense and sensibilities stand for a set of ways ofbeing that emphasize inter-wovenness, shape-shifting flexibilityand layered time; where the world is experienced through sensorial eventsinvolving movement, rhythm, sound and metaphor; where every “thing” (including humans, non-humans and theland) is a living entity; where every entity is valued for its intrinsic (insufficient andindispensable) inherent worth within an integrative anddynamic whole; and where their self-worth is grounded on their connectionwith something beyond the individual self, but also foundwithin it.ImplicationsWays of beingBrick sensibilities are goal- and progress-oriented. Theydemand that we share the same convictions about reality inorder to engineer proper political, ideological and institutionalstructures that will in turn engender adequate social relations(i.e., adequate conditions will build adequate institutions thatwill secure adequate relationships). The focus on engineeringreality is knowledge-based, methodological and grounded onconsensual decision making. Human purpose can be imagined14 Towards Braiding

as building monuments and walls that will last and leave a traceable legacy that attests to the worth and virtue of the individualsinvolved in contributing towards the imagined idea of progress.Conversely, thread sensibilities are oriented towardsrelationality. They require that we sense entanglement in orderto weave genuine relationships, which will in turn commandresponsibility for collective wellbeing as a grounding force foradequate (new) political and institutional systems (i.e. adequaterelationships will build adequate capacities to work together thatwill secure adequate processes). The focus on collective wellbeing invites the surrender of individual entitlements for a greatergood and calls for a level of ongoing stretch-discomfort within acontainer of relational interdependence that is unconditional inits generosity over time, but not open to abuse. Human purposeis associated with respecting the unique medicines that eachbeing carries and integrating these medicines to enable thecontinuity of life. In contrast with the brick sensibility’s preoccupation of leaving a legacy, the thread sensibility focuses onecological sustainability and aims at having minimal impact onthe world (e.g. leaving no footprints).Ways of knowingBrick sensibilities take language to be something that describesand indexes the world. Knowledge is something that can bediscovered and/or transmitted, and accumulated. This accumulation is documented in writing, therefore knowledge can bemostly found in books and formal institutions. Knowledge ismeasured according to its capacity for accuracy in describing,predicting or building effectively, and is something people feelentitled to, although they may need to pay for it.Bricks and Threads 15

Thread sensibilities take language to be both practicaland metaphorical. Language can never describe the unknowable wholeness of the world, but it is extremely useful to movethings in the world. In this sense, both language and knowledgeare “entities” whose impact is evaluated not by their accuracyin describing something, but in their impact in the world (i.e.,what they enable and what they foreclose). In this case, knowledge can come from many places (the land, altered states ofconsciousness, non-humans) and is something that is earned(not an entitlement).CommunicationBrick sensibilities tend to communicate through “thick scripts”of normativity, protagonism (individualistic heroism), reasonand virtue that take different forms in different contexts. Threadsensibilities tend to communicate through modes of self-effacement, relationship-weaving, intro/inter-spection and metaphorthat are “thin-scripted” as they are grounded in the unknown andunknowable.In modern institutions/relationships, which are ordered bybrick sensibilities, thread communication and sensibilities tend tobe muted/rendered unintelligible. Therefore, those from the threadspace who want to “be heard” in those institutions need to learnto translate their message into the mode of communication thatis legible to the dominant brick sensibility. This is not only deeplyfrustrating, but also often ineffective, pushing the orientationtowards a non-generative manifestation. Thread practices are alsooften selectively adopted/instrumentalized by brick orientationsas a means to improve effectiveness, to enact “inclusion” or as abranding “currency” of diversity, decolonization or Indigeneity.16 Towards Braiding

Important caveats There are a variety of brick sensibilities and a variety ofthread sensibilities, but it is important to notice that thesevariations are broadly clustered around different propositionsabout the nature of knowledge and reality (and the relationship between the two). The sensibilities of both bricks and threads can manifest ingenerative and non-generative ways. The universalization of bricks or threads is highly problematicas it makes invisible the limitations of the sensibility thatseeks universalization and attempts to delegitimize and/orerase the other sensibility. Social groups that depend on a deep relationship with theland as a living entity tend to lean towards the thread sensibility. Social groups that see the land as an object, resourceor property lean towards the brick sensibility. Indigenous groups are known to work with and throughthreads, while colonialism is known to violently imposebricks. While it is important to highlight that settler–Indigenousrelations are grounded on the harm that bricks have inflictedon threads, it is also important to complicate this relationshipby acknowledging that many Indigenous groups and individuals have adopted brick-related ways of being and a fewsettlers have developed senses and sensibilities that enablethem “to thread” (and some are penalized for that). Despite threads being used in political and academicdiscourse to characterize the struggle of Indigenous peoples,it is problematic to directly or universally equate IndigeneityBricks and Threads 17

with threads, partly because of historical circumstances thathave privileged the power and allure of the bricks. For those over-socialized in contexts where the brick sensibility is the universalized norm and perceived to be rational,neutral, universally desirable, and objective, it is very difficultto grasp that other people (coming from a thread sensibility) could feel the world very differently. As a result, withinbrick spaces threading is perceived as wrong, disingenuous,irrational or impossible. The integrity of the thread sensibility is often compromisedby the institutional demands and perceived entitlements ofthe brick sensibility that are normalized and naturalized as“common sense”. Brick sensibilities tend to intrumentalize thread methodologies (ways of doing) for their purpose, when convenient,often without the ability to recognize or to honour the waysof knowing and being where these methodologies camefrom. When brick sensibilities engage in processes of inclusion,they generally require threads to be turned into bricks, sothat they can become intelligible in the brick wall. Acts of transgression that challenge brick normativitiesare not necessarily a manifestation of the thread sensibilities: bricks often manifest as a competition of differentnormativities.18 Towards Braiding

BraidingWe define braiding as a practiceyet-to-come located in a spacein-between and at the edges ofbricks and threads, aiming to calibrate eachsensibility towards a generative orienta-tion and inter-weave their strands to create something new andcontextually relevant, while not erasing differences, historicaland systemic violences, uncertainty, conflict, paradoxes andcontradictions.Braiding is not a form of synthesis in which two approachesare combined in order to create a new, third possibility to replacethem both. Braiding is also not the result of selective, “saladbar”-style engagements with both sides, taking the “best” ormost convenient elements of each and combining them; nor is itthe result of an antagonism in which one side emerges triumphant over the other. Instead, braiding is premised on respectingthe continued internal integrity of both the brick and threadorientations, even as neither side is static or homogenous,and even as both sides might be transformed in the process ofbraiding. Braiding opens up different possibilities for engage-21

ment, without guarantees about what might emerge from thoseengagements. Braiding is not an endpoint, but rather an ongoingand emergent process. It is not possible to determine what braiding will look like before it occurs. In fact, we propose three “stepstowards braiding” that need to happen before any braiding iseven possible. They are described in the next section.Before braiding can happenAlthough brick and thread sensibilities appear to be incommensurable, it is at the edge-interface of each of these orientationsin their generative manifestation that the potential for newimaginings and adjacent possibilities in braiding emerges. Inthe collaborative processes with Indigenous and non-Indigenousparticipants that ground the development of this document, weshared the brick and threads metaphor and asked participantsto identify what could support or hinder practices of braiding. These conversations inform the “steps towards braiding”presented below. Before braiding can even start to happen, threelong steps are necessary:1.a deep understanding of historical and systemic harmsand their snowball effects needs to become “commonsense,” and not something to be avoided, dismissed, orminimized out of a fear of hopelessness, guilt or shame;2.a language that makes visible the generative andnon-generative manifestations of bricks and threadsneeds to be developed, without becoming rigid,prescriptive or accusatory;22 Towards Braiding

3.a set of principled commitments towards the “long-haul”of this process needs to be in place, including a commitment to continue the work even/especially when thingsbecome difficult and uncomfortable.We offer a cautionary note about a common misreading ofthese steps, which assumes that achieving these steps equatesto actually doing braiding work. In fact, these are only theminimum necessary conditions that must be in place in order forbraiding to even become possible; these conditions are not thebraiding work itself, and further, these conditions alone will notnecessarily lead to braiding. As well, these steps might need tobe continuously revisited, as we tend to forget them when thingsget difficult. We expand on each of the “steps towards braiding”below.Step 1: Facing and digesting the implicationsof historical and systemic harmThe political, material, institutional, and cognitive impositionsand attempts to universalize the sensibility and weight of bricks,and to eliminate and/or instrumentalize the threads, is ongoingand has lasting effects. Indigenous participants identified that itis extremely common to see liberal organizations creating conditional spaces for Indigenous inclusion that foreground the bricksensibility as a default disposition towards shared futures that isnormalized and perceived as natural. In other words, threads areincluded into the organization on the condition that they contortthemselves into the shape of a brick. This includes, for example,organizations expecting: that the inclusion of Indigenous peopleBraiding 23

will placate criticisms of colonialism; that Indigenous staff/artists will be able to mediate the relationship of the organizationwith all Indigenous communities; that Indigenous staff/artistsand their communities will be willing to “move forward” towardsthe idealized future anticipated by the organization; that Indigenous staff/artists and communities will be grateful for the opportunity to perform selected, non-threatening aspects of theirculture when the organization deems appropriate; that Indigenous staff/artists and communities should have a commitmentto harmonious relationships; and that Indigenous staff/artistsshould perform loyalty to the organization by not challenging theterms of inclusion.Participants also identified that the current political andintellectual climate makes it possible for criticisms of conditionalinclusion to be articulated at this specific historical moment,something that might not have been possible ten years ago.Rather than suggest that these criticisms or the frustrations thatare expressed within them are new, we suggest that there hasbeen an increased awareness of conflictual settler–Indigenousrelationships in recent years, as the excerpts from the poem,“Academic Indian Job Description: Have to Know” by CashAhenakew, illustrates.Academic Indian job description: have to knowby Cash Ahenakewhave to knowwestern knowledge and educationplus the critique ofwestern knowledge and education24 Towards Braiding

have to knowindigenous “culture” and educationplus the critique and the critique of the critique ofindigenous “culture” and educationhave to knowhow to embody expected authenticityand how to embody expected critiqueof expected authenticityhave to knowwhen and where to use indigenous literatureand when and where to use the Western canonto build legitimacy and credibility for indigenous thoughtand experiencehave to knowwhen to vilify, to romanticize, to essentializewhen to apologize, to complexify, to compromisewhen and who to be accountable to and whyhave to knowwhen, where and how to performcompetence, confidence, boldness, heroic rebelliousnessand humility, compliance and gratitude for the opportunityBraiding 25

have to knowhow to be an intellectual, an activist, a therapist, and anentrepreneurhow to improve retention, attrition and social mobilityand how to stop exploitation and ecological disasterhave to knowhow to educate “my people,” liberal allies, immigrants, rednecks, colleagueshow to relate to gang members, business sponsors, elders,politicianshow to speak with the crows, the trees, the sea, and the mediahave to knowhow to solve, how to fix, how to spell and to pronouncecolonialism, capitalism, racism, slavery, patriarchyhetero-normativity, ableism, elitism, and anthropocentrismhave to knowhow to Indigenize and decolonizedisciplines, protocols, ethics and methodologiesto make non-indigenous people feel good about their workhave to knowhow to live with the guilt of having credentials, a secure joband the awareness of compliance with a rigged systembuilt on the broken back and wounded soul of your familymembersApply online now26 Towards Braiding

As the poem demonstrates, when “including” other perspectives brick sensibilities rarely question their own presumeduniversalism. Thus, the act of inclusion in itself becomes ameans for the brick sensibility to reclaim universality: whereasit once excluded difference, now it embraces it and therebybecomes all the more totalizing. What remains unquestionedhere is not only who decides the terms of inclusion, who benefits, and how, but also the assumption that exclusion fromuniversalism is the primary basis of colonial relationships and,thus, that inclusion into the brick sensibility is the only viableand desirable means of addressing colonial harm. When theseassumptions are not questioned, diverse/Indigenous bodies areinstrumentalized within a brick framework for the benefit oforganizations, and thread visions, futurities, and sensibilities aresilenced once again.Because the brick orientation sets the terms of inclusion andmaintains the power to issue (and rescind) the invitation to beincluded, this approach to change does not disrupt and in factreinforces colonial desires and entitlements. For instance, theperceived entitlement to authority and leadership is reinforcedwhen those with a brick orientation retain the right to adjudicatewho is included (and excluded) and under what conditions theyare invited and allowed to stay. The perceived entitlement tosimplistic, readily available solutions is reinforced when thosewith a brick orientation presume that including an Indigenousstaff member alone will address centuries of systemic colonialviolence and absolve their organization of complicity in it. Theperceived entitlement to have one’s benevolence affirmed isreinforced when those with a brick orientation present themselves as generous for including difference, and believe thisBraiding 27

entitles them to redemption for colonial violence. Despiteor perhaps precisely because of these colonial continuities,“inclusion” is often mobilized as a

10 Towards Braiding meaningful in peoples' lives, in our communities and societies. This collaboration involved several modes of relational engage-ment with Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists, scholars, and communities, including visits, gatherings and consultations,