Transcription

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology1985, Vol. 48, No. 6, 1520-1533Copyright 1985 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.0022-3514/85/S00.75Desire for Control and Achievement-Related BehaviorsJerry M. BurgerUniversity of Santa ClaraA model is presented that describes the relation between individual differences inthe general desire to control events and performance in achievement-related tasks.Six experiments were conducted with a college-student population to examinevarious steps in this model. Subjects high in the desire for control displayedhigher levels of aspiration, had higher expectancies for their performances, andwere able to set their expectancies in a more realistic manner than were subjectslow in the desire for control. Subjects high in desire for control were also foundto respond to a challenging task with more effort and to persist longer at adifficult task than were subjects low in desire for control. Finally, a pattern ofattributions for success and failure was uncovered for subjects high in desire forcontrol that has been associated with high achievement levels.The construct of personal control has generated a considerable amount of research recently (cf. Baum & Singer, 1980; Garber &Seligman, 1980; Lefcourt, 1981, 1982; Perlmuter & Monty, 1979). The prediction of,motivation for, and reaction to the loss ofpersonal control has been tied to numeroussocial-psychological phenomena. These includedepression (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale,1978), academic performance (Dweck & Licht,1980), health (Wallston & Wallston, 1981),pain tolerance (Thompson, 1981), crowding(Schmidt & Keating, 1979), and adjustmentamong the elderly (Schulz, 1980).A natural extension of this research hasbeen the examination of individual differencesin the motivation to obtain control or to bein control of a situation. In this vein, Burgerand Cooper (1979) introduced the notion ofdesire for control, a stable personality traitreflecting the extent to which individualsgenerally are motivated to control the eventsin their lives. Persons high in desire forcontrol are said to prefer making their owndecisions, taking action to avoid a potentialloss of control, and assuming leadership rolesPortions of this research were presented at the meetingof the American Psychological Association, Anaheim,California, August 1983.The author would like to thank Cynthia Allen, WilliamKraft, and Alicia Lopes for their help with the datacollection.Requests for reprints should be sent to Jerry M.Burger, Department of Psychology, University of SantaClara, Santa Clara, California 95053.in group settings. Persons low in desire forcontrol are motivated to avoid extra responsibilities and may prefer that someone elsemake decisions for them.To examine this individual difference, Burger and Cooper (1979) designed the Desirability of Control (DC) Scale. The DC scalehas been found to have reasonable psychometric properties, is only slightly correlatedwith measures of locus of control, and isrelatively independent of social desirability(Burger, 1984; Burger & Cooper, 1979; Smith,Wallston, Wallston, Forsberg, & King, 1984).Working with the scale, researchers havefound that DC scores can account for significant proportions of variance in a wide varietyof areas. These include learned helplessness(Burger & Arkin, 1980), gambling (Burger &Cooper, 1979; Burger & Schnerring, 1982),choice of a place to die (Smith et al., 1984),intrinsic motivation (Burger, 1980), attitude change (Burger & Vartabedian, 1980),depression (Burger, 1984), perceptions ofcrowding (Burger, Oakman, & Bullard, 1983),and type of photographs taken (Henry &Solano, 1983).The present series of experiments is designed to examine the role of individualdifferences in the desire for control inachievement-related behaviors. Research onachievement motivation and achievement-related behavior extends from classic earlyworks (e.g., Atkinson, 1964; McClelland,1961) to recent interest in more complexmodels and in a variety of related variables1520

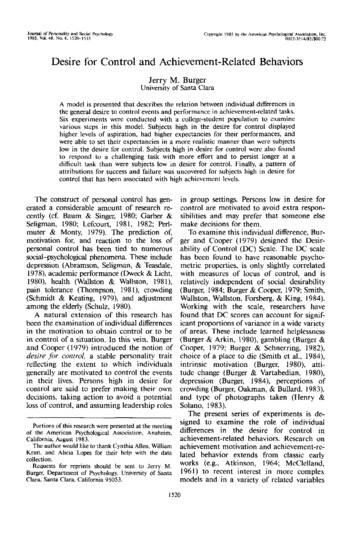

DESIRE FOR1521CONTROLAspiration LevelHeaponsa loChallengePersistenceAtlrtbutlons forSUCCMS A FailureTheoreticalSelect harderReact withWork at difficultHigh DC as Comparedwith Low DCmore realisticallyHigh-DC BenefitHigher goalsare achievedDifficult tasksDifficult tasksare completedMotivation levelremains highHigh-DC LiabilityMay attemptgoals toodifficultMay developper'ormanceinhibitingreactionsMay invest toomuch effortMay develop anillusion ofcontrolMore likely toto self and failureFigure I. Four-step model for the relation between desire for control and performance on achievementrelated behaviors.(e.g., Spence & Helmreich, 1983; Thomas,1983). The present series of studies representsan initial effort to examine how individualshigh and low in desire for control differ intheir behavior at several steps along anachievement-behavior sequence.I propose that individuals high in the desirefor control will display many of the behaviorsthat are related to higher achievement. Morespecifically, desire for control will have asignificant influence on this behavior at fourdifferent steps in the task sequence. The stepsin this sequence are illustrated in Figure 1.First, persons high in desire for control shouldhave higher levels of aspiration for their performances than do persons low in desire forcontrol. In addition, these individuals shouldselect aspiration levels that more realisticallyreflect their potentials. These predictions follow from the conception of an achievementtask as a challenge to the individual's perception of personal control. Success at the taskdemonstrates one's ability to control suchsituations and one's mastery generally. Onthe other hand, failure to conquer the taskmay be interpreted as a threat to one's perceived ability to control significant segmentsof the environment. Thus, persons high inthe desire for control should be highly motivated to perform well on a challenging task,and this should be manifested in high levelsof aspirations. However, unrealistically highaspirations can result in the unwanted failureexperience. Therefore, persons high in desirefor control should have learned to realisticallyset their aspirations in a manner that maximizes their perception of achievement.The second step in the model concerns theindividual's response to a challenge. Manyreal-world tasks in achievement settings arefilled with unexpected difficulties. I hypothesize that persons high in desire for controlwill respond to these difficulties as challengesto their control over the task. Thus, thereactance effect (Brehm, 1966) of exertinggreater effort when one meets such a challengeshould be found more often among thosehigh, rather than low, in the desire for control.Similarly, persons high in desire for controlshould be more persistent in their efforts tocomplete a difficult task—the third step inthe sequence. Because they are highly motivated to avoid failure, and thus to avoid theperception of a lack of control, persons highin the desire for control should work at adifficult task for a longer time before givingup or seeking help than do persons low inthe desire for control.Finally, individuals high in desire for control should attribute the causes of their performances in a manner that increases motivation on subsequent tasks. Research by Weiner et al. (1971) demonstrated that highachievement is associated with giving oneselfcredit for successes (e.g., high ability, higheffort) and attributing failure to a lack ofeffort or to luck. These attributions are saidto influence how the person approaches andworks on future tasks; this pattern leads tohigher motivation and thus more achievement. I propose that persons high in desirefor control are motivated to perceive themselves as responsible for their successes andthereby satisfy their motives to feel personallyin control of the situation. In addition, a highdesire for control should lead these same

1522JERRY M. BURGERindividuals to deny any inability to controlthe situation (i.e., failure) and, therefore, toattribute such instances to unstable sources.Although it is intuitively appealing on thesurface, this four-step model would be overlysimplistic in describing the relation betweendesire for control and performance onachievement-type tasks. Although the hypotheses all point to the superiority of theperson high in the desire for control over theindividual low in desire for control, this iscertainly not always the case. At each step ofthe model it is possible that a high desire forcontrol also can become a liability. A highlevel of aspiration, for example, may lead tothe person's attempting tasks that are toodifficult to be accomplished. The person highin desire for control also might be more likelyto take on too many tasks, thus inhibitinghis or her ability to perform well on any ofthem.Similarly, although persons high in desirefor control may react to challenges with increased effort, at some point the inabilityto control the situation may cause themto develop performance-inhibiting reactions.Wortman and Brehm (1975) proposed thatthose individuals who react most strongly toa threat to perceived control are most likelyto suffer helplessness reactions if the situationremains uncontrollable. Consistent with theWortman and Brehm model, Burger andArkin (1980) found that persons high in thedesire for control exhibited more helplessnessbehavior and reported higher levels of depression following a learned helplessness manipulation than did subjects low in desire forcontrol. Similarly, Burger (1984) found thatpersons high in the desire for control whogenerally perceived that they did not havecontrol over the events in their lives weremore likely to exhibit some depressive symptoms than were persons low in desire forcontrol. Thus, although the tendency to reactto a challenge with greater effort may bedesirable for some tasks, it also may holdsome serious pitfalls.Whereas persistence on a task can oftenlead to the solving of a difficult problem, italso can lead to an inefficient investment oftime and effort if the task eventually provesto be too difficult. Finally, although attributions to oneself for success may lead to higherlevels of motivation on later tasks, this tendency also can become a liability. Not recognizing when one's successes are caused byexternal forces and not accepting responsibility for one's failures may give the individualhigh in desire for control a false impressionof his or her abilities. Persons high in thedesire for control mistakenly may attempt tocontrol events over which they have little orno influence. Burger and Cooper (1979) andBurger and Schnerring (1982) found thatpersons high in desire for control were moresusceptible to the illusion of control thanwere persons low in the desire for control.Under certain gambling situations these subjects tended to place larger bets, indicative ofa greater confidence of success, for gamesthat were obviously chance determined thandid subjects low in desire for control.The complete model for the relation between desire for control and achievementrelated behavior is presented in Figure 1. Ascan be seen, a complete understanding of thisrelation requires that the model be tested atnumerous points to determine the circumstances under which different levels of desirefor control lead to different types of behaviorsand different outcomes. The purpose of thepresent series of experiments is to test theproposed positive relation between desire forcontrol and behaviors associated with highlevels of achievement at each of the foursteps in the model. Limiting conditions andthe influence of other variables on theserelations need to be examined in later research.Experiment 11 propose that desire for control is positivelyrelated to level of aspiration on an achievement-type task. Persons high in the desire forcontrol should be more likely to select tasksthat provide a challenge than should personslow in desire for control. In this way thecompletion of the task can provide a senseof mastery and control. Although the selectionof a relatively easy task might ensure success,such an accomplishment would provide littlesatisfaction for the person who is motivatedto perceive himself or herself as in control.On the other hand, persons low in the desirefor control are not as strongly motivated to

DESIRE FOR CONTROLsense control through achievements, andtherefore may be satisfied to accomplish thenecessary work with a minimal chance offailure. These persons low in desire for controlmay be expected to select a task that allowsfor completion, even though it may not provide much in the way of perceived control. Itwas predicted that when given a choice oftasks of different difficulty, persons high inthe desire for control would tend to selecttasks that are more difficult than would persons low in the desire for control.MethodSubjects. Thirty-four male and female undergraduatesserved as subjects in exchange for class credit. All hadtaken the Desirability of Control Scale (Burger & Cooper,1979) approximately 4 weeks earlier as part of a largetest battery. No connection was made between the experiment and the DC scale at the time of the experiment, aprocedure that was followed in Studies 2-5, as well.Instrument. The DC scale is a 20-item inventory thatasks subjects to indicate on 7-point scales the extent towhich they agree or disagree with statements concernedwith issues of control (e.g., "I prefer a job where 1 havea lot of control over what I do and when I do it," "I wish1 could push many of life's decisions off on someoneelse"). Scores range from 20 to 140, with higher scoresindicating a higher desire for control. Means with collegestudent samples have consistently averaged between 100and 105.Procedure. Subjects participated in the experimentin groups. They were told that the experimenter wasinterested in examining verbal abilities. Subjects wereinformed that they would be working on a series ofanagram tasks. It was explained that the presentation ofthe anagrams would be in two parts. During the firstpart each subject received a test booklet containing foursets of 10 anagrams, one set per page. The experimenterexplained what anagrams were and gave an example.Subjects then were given 2 min each to solve the foursets of 10 anagrams, with the experimenter starting andstopping subjects for each set. All anagrams consisted offour letters and were designed to be only mildly difficult.Subjects then were instructed to turn to the last pageof the booklet. On this page, subjects found the instructions for selecting the level of difficulty for the anagramsthey would work on during the second part of theexperiment. It was explained that the subject would workon three more sets of 10 anagrams. The subject was toindicate which three of the possible nine sets he or shewished to work on and in what order they were to begiven. It was explained that the sets had been normedwith a large number of college students and that each setwas identified on the sheet with a difficulty rating. Thedegree of difficulty for each set was indicated by thepercentage of subjects in the normed group who supposedly were unable to solve all 10 anagrams. The nine setsranged from anagrams in which 90% of the normedgroup had been unable to solve all of the problems to a1523set in which only 10% had been unable to complete allof the anagrams. The remaining sets were presented in10% increments. Thus, each of the three choices madeby the subjects could be assigned a value from 1 to 9 forthe degree of perceived difficulty. Subjects were told theycould select each of the sets only once.Following these choices, subjects were informed thatthere would be no more anagram problems. The subjectswere debriefed and dismissed.Results and DiscussionSubjects were divided into high- and lowdesire-for-control (DC) halves via a mediansplit method. First, each group was comparedfor performance on the anagram task. Thetotal number of solved anagrams on the foursets (40 total anagrams) was calculated foreach subject. As can be seen in Table 1, nosignificant difference was found between highand low-DC subjects in terms of performanceon the anagram task.Next, subjects' aspirations were assessed intwo ways. First, the anagram set that thesubject desired to work on first was examined.Next, the three choices of anagram set weresummed for an overall aspiration score. Ascan be seen in Table 1, significant differencesbetween high- and low-DC subjects emergedon both of these measures. High-DC subjectschose an anagram set for their first choicethat was significantly more difficult than theset chosen by low-DC subjects, F(\, 32) 5.34, p .03. In addition, the overall aspiration score for high-DC subjects was higher—indicating a choice of more difficult anagrams—than was the score for the low-DCsubjects, F(l, 32) 5.30, p .03.The results of Experiment I, therefore,provide support for the first step in the desirefor-control-achievement-behavior modelproposed here. Although high- and low-DCsubjects performed equally well on the sampleanagrams, the high-DC subjects preferred towork on tasks that they believed to be ofgreater difficulty than did the low-DC subjects.In actual achievement situations, high-DCpersons can be expected to attempt jobs orto take classes that are perceived to be difficultmore readily than will low-DC persons. Thisis consistent with the conception that thehigh-DC individual finds satisfaction in displaying mastery over tasks that he or shefinds challenging.

1524JERRY M. BURGERTable 1Mean Correct Anagrams and Choices by Highand Low-DC SubjectsSubjectsdicate on the spaces provided at the bottom of the pagehow many numbers they had connected on that puzzleand to estimate how many they would connect on thenext puzzle.Results and DiscussionVariableHigh-DCLow-DCNumber correctFirst choiceTotal choice35.306.1219.3535.414.2916.23Note, DC desire for control.Experiment 2If desire for control is related to level ofaspiration in an achievement-related task,then one would expect that higher DC scoreswould be related to higher expectancies ofsuccess on the task. In addition, it has beenproposed that higher levels of desire for control will be associated with more realisticexpectancies and aspirations. High-DC peopleshould not aspire to levels too high to meetand thus exclude a feeling of accomplishment.In addition, because high-DC individuals aremotivated to perform well, they may paycloser attention to performance feedback andadjust their aspirations accordingly more thando low-DC persons. Experiment 2 comparedexpectation levels of high- and low-DC subjects. It was predicted that high-DC subjectswould give higher and more accurate estimatesfor their performances than would low-DCpersons.MethodSubjects. Eighty-five male and female undergraduatesserved as subjects in exchange for class credit. All hadtaken the DC scale several weeks earlier as part of a largetest battery.Procedure. The procedure was similar to that usedin an experiment by Snow (1978). It was explained tosubjects that they would be working on a series ofconnect-the-numbers puzzles to assess their perceptualand motor skills. Subjects received a booklet containingthe puzzles. It was explained to subjects that each puzzleconsisted of the numbers 1-50, scattered randomly aroundthe 8Vi X ll-in. (21.8 X 28-cm) page. Their job was tobegin with the number 1 and connect the numberssequentially as rapidly as possible. Subjects were informedthat they had 20 s to work on each puzzle.On the first page of the booklet, subjects were askedto indicate how many numbers they thought they wouldbe able to connect within the 20-s lime period for thefirst puzzle. The experimenter then started and stoppedsubjects on each of the six puzzles in the booklet. Aftercompleting each puzzle, subjects were instructed to in-Three different measures were created fromthe subjects' responses. Each of these wasthen correlated with the DC score. First,there was a significant correlation betweenDC score and the estimate subjects made forthe first puzzle (r .31, p .01). The higherthe DC score, the higher the subject tendedto estimate his or her performance on theunseen task. Next, the six estimates for thepuzzles were summed for an overall aspirationmeasure. Once again, this score was positivelycorrelated with the DC score (r .28, p .01), indicating higher overall aspiration levelsfor those with higher DC scores. Finally, ameasure of subject accuracy of estimationwas calculated. For each puzzle the completednumber was subtracted from the estimate forthat puzzle. The absolute values of each ofthese figures were then summed for an accuracy index. This accuracy score correlatednegatively with the DC score (r -.38, p .001). Thus, higher DC scores were associatedwith smaller differences between the estimatefor a puzzle and the actual performance onthe puzzle.The results of Experiment 2 provide additional support for the first step in theproposed model. On both the initial puzzleand the puzzles taken together, high-DC subjects tended to make higher estimates of theirperformance than did low-DC subjects. Theseestimates can be interpreted as another demonstration of the higher levels of aspirationproposed for high-DC persons. In addition,high-DC persons tended to be more accuratein their estimates of their performances. Thisfinding is consistent with the description ofthe high-DC person as one who is highlymotivated to demonstrate his or her mastery.These subjects set their aspirations on a levelwhere they were more likely than were lowDC subjects to attain the goal and, thus, toestablish their competence.Experiment 3The second stage of the model proposesthat persons high in the desire for control

DESIRE FOR CONTROLwill respond to a challenging task with greatereffort than will low-DC individuals. A taskthat becomes more difficult than was originally anticipated should be perceived by thehigh-DC individuals as a threat to their control over the task. These individuals shouldthen respond with greater effort to overcomethe challenge than should low-DC persons.In research on a related construct, Fazio,Cooper, Dayson, and Johnson (1981) foundthat Type A college students worked harderon a proofreading task when the task wasmade challenging than when the task was arelatively simple one. Type B persons showedthe opposite effect. Glass (1977) suggestedthat the primary distinction between Type Aand Type B persons is a higher level ofmotivation to control the environment by theType A individual. Indeed, Musante, MacDougall, Dembroski, and Van Horn (1983)found that DC scale scores were significantlycorrelated with various measures of Type AType B. Because of this proposed similaritybetween the Type A-Type B construct andthe DC construct, both were examined in theexperiment.A procedure similar to that used by Fazioet al. (1981) was employed. Subjects workedon a proofreading task that was either relatively easy or fairly challenging. It was predicted that higher desire-for-control scoreswould be associated with higher levels ofeffort on the proofreading task, but only inthe challenging condition.MethodSubjects. Thirty-nine undergraduates participated inthe experiment in exchange for class credit. All had takenthe DC scale and a measure of Type A-Type B, thestudent version of the Jenkins Activity Survey (JAS;Glass, 1977), several weeks earlier.Procedure. Subjects participated in the experimentin groups. Subjects were given a red marking pen and amanuscript filled with errors. They were informed thatthey would be working on a proofreading task. Theexperimenter explained that the subject's task was tolook for errors in spelling, punctuation, and grammar.Examples of how to indicate and correct errors weregiven. In the challenge condition, subjects were given twoadditional tasks to perform. They were instructed tocount the number of times the word the appeared andalso the number of proper nouns that appeared on thelines they were proofreading. Subjects in the no-challengecondition were given the proofreading task only.All of the subjects were given 10 min to work on thetask. At the end of the time, the experimenter stopped1525the subjects and instructed them to draw a line indicatingthe last full line of the manuscript that had been proofread.Subjects in the challenge condition were instructed toindicate how many times they had read the word the andhow many proper nouns they had seen to that point inthe manuscript. All subjects then were debriefed.Results and DiscussionSubject scores for the DC scale and theJAS were significantly correlated (r .39,p .02). Because of this correlation, analysisof the dependent measure, the number oflines attempted, was conducted with multipleregression analyses. The DC and JAS scores,along with a challenge-no-challenge dummyvariable, were entered into the regressionanalysis, producing an overall R2 of .18. Asignificant effect for the challenge variablewas found when it was entered into theanalysis first, F(l, 35) 4.17, p .04. Subjects in the no-challenge condition attemptedmore lines (M - 35.1) than did subjects inthe challenge condition (M 30.1). TheDC X Challenge interaction fell short ofsignificance, F(l, 35) 2.39, p .13, andthe AB X Challenge interaction was far fromsignificant (F I ) . No other significant effectswere found in these analyses.To better understand the relation betweenDC score and the dependent measure, separate regression analyses were conducted forthe challenge and no-challenge conditions.First, for subjects in the challenge condition,the JAS score was entered into the regressionanalysis. The results indicate that the JASscore was not a significant predictor of thenumber of lines attempted (F 1). With thevariance accounted for by the JAS removed,the DC score was entered into the regressionanalysis. The DC score proved to be a significant predictor of the measure, F(l, 16) 4.25, p .05. When entered into the regression analysis in the opposite order, the DCscore, entered first, approached significance,F(\, 16) 3.69, p .07, whereas the JASscore, with the DC variance removed, againfailed to predict the measure. The higher theDC score, the more lines the subject in thechallenge condition was likely to have attempted. When the total lines measure wasexamined within hierarchical multiple regression analyses for the no-challenge subjects,no significant effects were found.

1526JERRY M. BURGERThe results of Experiment 3, therefore,provide some support for the second step inthe desire-for-control-achievement-behaviormodel. It was found that higher desire forcontrol was associated with greater effort onthe proofreading task, as indicated by thenumber of lines attempted, when the taskwas made a challenging one by the additionof two tasks. When the task was a simpleproofreading task, no effect for desire forcontrol was found. Although the experimentwas a fairly vague laboratory task, the behavior in the challenge condition can be seen assomewhat typical of behavior in real worksettings. At higher levels of achievement,workers often are called on to perform tasksthat require the ability to alternate one'sfocus of attention and to coordinate severaldifferent aspects of a task. The results suggestthat persons high in the desire for controlreact to such challenging jobs with greatereffort in an attempt to overcome the challengeand establish the perception of control overthe situation. However, no differences betweenhigh- and low-DC persons may be expectedfor jobs that present relatively low levels ofchallenge. Although they probably are motivated to avoid failure in this situation, highDC individuals are not challenged enough toput forth the increased effort, as they are onthe more difficult task.Although the above analysis is consistentwith the proposed model, note that subjectsin the challenge condition had a more difficulttask and therefore attempted fewer proofreading lines overall than did the no-challengesubjects. Because of this, it is not possible todetermine if the high-DC subjects reacted tothe challenge with increased effort or if thelow-DC subjects responded to the challengewith decreased effort, or if both conditionswere the case. Nonetheless, the difference inhigh-DC and low-DC persons' reactions tothis situation has been demonstrated.One additional interesting finding was thefailure of the Type A-Type B variable topredict behavior in either of the two types oftasks. Although there are some methodological differences between the two experiments,Experiment 3 represents a failure to conceptually replicate the Fazio et al. (1981) findings.It is also interesting to note that althoughthey are conceptually similar, the desire forcontrol and Type A-Type B constructs weredemonstrated to have a practical and empirical distinction.Experiment 4The third step in the proposed model isconcerned with the individual's persistenceon a difficult task. I propose that personshigh in desire for control are more likely topersist at working on a difficult task than arepersons low in the desire for control. For ahigh-DC individual the difficult task may beperceived as a challenge to his or her abilityto control the situation. To give up on sucha task is tantamount to admitting that onehas encountered a task that he or she cannotcontrol. It obviously would be incorrect toassert that high-DC persons never admit thatthey can not accomplish a task. However, ina situation in which it is strongly impliedthat the task is not impossible, merely difficult, the high-DC person can be expected tocontinue efforts to complete the task muchlonger than can the low-DC individual, whomore readily admits to an inability to controla task. The high-DC worker who is given adifficult task on the job naturally will assumethat the task can be completed with enougheffort, and thus can be expecte

achievement-behavior sequence. I propose that individuals high in the desire for control will display many of the behaviors that are related to higher achievement. More specifically, desire for control will have a significant influence on this behavior at four different steps in the task sequence. The steps in this sequence are illustrated in .