Transcription

LIFECYCLEThe BTO Magazine for Ringers and Nest RecordersWOODPIGEON NESTINGTRAPPING TECHNIQUESPOST-JUVENILE MOULTOpportunity to explore variationin Blue TitsAUTUMN 2018ISSUE 8AGEING REED BUNTINGS

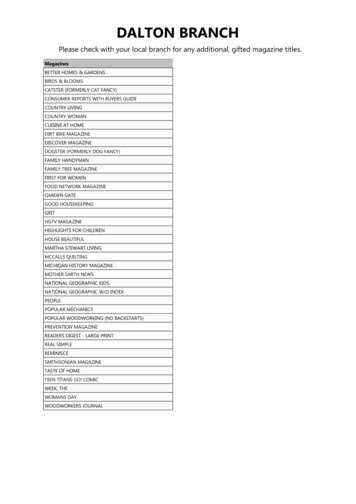

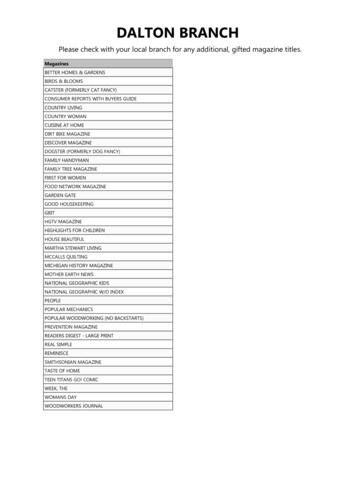

EDITORIAL Editorial and ContentsEditorialLIFECYCLEISSUE 8 AUTUMN 2018Welcome to the autumn edition of LifeCycle. After a long,The BTO Magazine for Ringers and Nest Recordershot summer and an unseasonably warm start to autumn, itseems hard to believe that winter is just around the corner.With most project ringing and nest monitoring finished foranother year and submissions starting to arrive here at BTOHQ, some of you may be looking for a project to get stuckinto this winter to fill the gap. If so, we are very pleasedto announce the launch of a new national moult projectlooking at post-juvenile moult in Blue Tits (everyone’sfavourite!), coordinated by volunteer David Norman – see page 4 for detailsabout how to get involved. And if you aren’t quite ready to give up your nestrecording for the year, head to page 6 to see how you can extend your nestingseason with the help of your local Woodpigeons.For anyone who has a burning desire to ring or nest record on Ministryof Defence land but are unsure how to gain access, the article on page 10 willbe of interest. This edition also includes articles on catching techniques forringing in your garden without a mist net (page 12), ageing Reed Buntings(page 15) and a novel nest-box project involving Shags (page 20). We alsointroduce an exciting new project to create a Eurasian African Bird MigrationAtlas (page 18).Thank you to everyone who has contributed to this edition; we would bedelighted to hear from anyone who would like to write, or contribute to, anarticle for a future edition and, as always, your feedback and suggestions forcontent would be welcomed. With the conference season nearly upon us, welook forward to meeting and chatting to some of you either at the ScottishRingers’ Conference or at Swanwick.WOODPIGEON NESTINGAUTUMN 2018ISSUE 8AGEING REED BUNTINGSTRAPPING TECHNIQUESPOST-JUVENILE MOULTExploring moult patternsin Blue TitsRuth Walker & Carl BarimoreLIFECYCLETHE BTO MAGAZINE FOR RINGERSAND NEST RECORDERSThe Ringing and Nest Record schemesare funded by a partnership of theBTO and the JNCC on behalf of thestatutory nature conservation bodies(Natural England, Natural ResourcesWales, Scottish Natural Heritage and theDepartment of Agriculture, Environmentand Rural Affairs, Northern Ireland).Ringing is also funded by The NationalParks and Wildlife Service (Ireland)and the ringers themselves. The BTOsupports ringing and nest recording forscientific purposes and is licensed by thestatutory nature conservation bodies topermit bird ringing and some aspects ofnest recording. All activities described areundertaken with appropriate licences andfollowing codes of conduct designed toensure the welfare of birds and their nestsis not adversely affected.CONTACT USThe British Trust for Ornithology is a charitydedicated to researching birds. For membershipdetails please contact: membership@bto.orgBritish Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery,Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PUTel: (01842) 750050Website: www.bto.orgEmail: ringing@bto.org, nrs@bto.org,ces@bto.org, ras@bto.orgRegistered Charity No 216652 (England & Wales)No SC039193 (Scotland)LIFE CYCLE PRODUCTIONLifeCycle is the biannual magazine of the BTORinging and Nest Record schemes. It is freelyavailable on the BTO website.IN THIS ISSUE . . .News from ringing and nest recording. 3Do you ring Blue Tits?. 4Woodpigeons: better late than never. 6T- and C-permit holder reps on RIN. 9Accessing the Defence Estate. 10No net – no problem!.12The challenge of ageing Reed Buntings. 15Obituary: Dr Iain Main.17A continental-scale Migration Atlas. 18Shags: a new nest-box species?. 20Publications. 22Noticeboard. 23Monitoring priorities: Greenfinch. 242 – LIFECYCLEArticles in LifeCycle are written by ringers and nestrecorders, so please send ideas and contributionsto the editors:Carl Barimore, NRS OrganiserEmail: nrs@bto.orgRuth Walker, Ringing Surveys OrganiserEmail: ruth.walker@bto.orgEditors:Carl Barimore, Ruth Walker, Richard Broughton &Dave Leech.Layout, design, imagesetting and typesetting:Hazel Evans, Ruth Walker & Mike Toms.Printing:Swallowtail Print, Norwich.Copy dates:Spring edition – 31 DecemberAutumn edition – 30 JuneThanks to the proof readers for all their efforts.Cover image: Blue Tit, by Liz Cutting/BTOThe views expressed by thecontributors to this magazine are notnecessarily those of the Editors, the BTOBoard or its committees. Quotationsshould carry a full acknowledgement. BTO 2018Autumn 2018

Ringing & Nest Recording NEWSBlackcap with retrieved geolocator, by Robbie PhillipsNEWS FROM RINGING & NEST RECORDINGSTAFFINGThere have been some recent staffchanges in the Ringing & NestRecording Team. Ros Green, who manyof you will have communicated withover the past year in her role as LicensingAssistant, has moved to a new positionwithin the BTO. Mark Grantham has,once again, agreed to step back into thefold and provide cover in the LicensingTeam, working remotely, two days aweek. We will also soon have to saygoodbye to Diana de Palacio. Diana,who has worked at the BTO for 14years, over 10 of which have been in theRecoveries Team, has moved south withher family, but will continue workingtwo days a week, remotely, until the endof the year. We welcome Mark back tothe team and wish Ros and Diana all thevery best in their future endeavours andthank them for all their hard work forthe Team.TO J OR NOT TO J?You may have read in the RingingCommittee papers, DemOn Manualand /or Facebook threads about theplan to remove the ‘J’ code from thelist of passerine age codes available.Please note that this change has not yetbeen implemented, so, until you hearotherwise please continue as you havealways done by using the 1J, 2J, 3J &5J codes where appropriate. The changehas been discussed at RIN and a finalpaper will be taken to Committee inadvance of the new coding system beinglaunched, which we aim to do by thestart of the 2019 breeding season.PERMIT RENEWALThis year’s permit-renewal process willstart, as usual, during the autumn for Tand C-permit holders, and by the newyear for A-permit holders. There willbe a few changes this year, which wereexplained in the email sent to all ringersa few weeks ago. If you have not receivedany emails about the renewal process bythe end of October please let us know.The changes have been prompted by themove to a new membership database,Civi-CRM, which replaces the oldAutumn 2018The team were able to retrieve the geolocator from this Blackcap. If you see a Blackcapwith a geolocator or colour rings, please contact a member of the team.Progress system in holding all licensingrelated details. We ask you to please takeparticular care to check that all yourcontact details are correct on the renewalform, and that everything you expect isprinted on your permit when you receiveit; if you spot any mistakes, or are unsureabout any aspect of the permit-renewalprocess this year, please contact us atringing.licensing@bto.orgWINTER BLACKCAP STUDY UPDATEThis study is using ringing, colourringing and tagging methodology toinvestigate the behaviour, movementsand breeding origin of overwinteringBlackcaps, as there is still much to learnabout which birds are stopping withus and how they are able to do so. Theaim is for the colour-ringing element tocontinue in the longer term, monitoringpotential trends in this apparently novelmigration strategy.After the second winter of intensivefieldwork, an impressive total of over200 wintering Blackcaps have nowbeen marked by a growing networkof over 25 ringers across Britain andIreland. The colour ringing is allowingus to build up a very detailed pictureof garden/feeder use, which is highlyvariable between individuals, with somevery interesting movements identified,both within and between winters.Geolocators have been fitted to atotal of 86 individuals during the lasttwo winters, to track their migrationroutes and identify breeding locations.Four geolocators were successfullyretrieved from the 2016/17 winterand we’re eagerly awaiting the returnof more in the coming months. Allgeolocator birds have colour ringscontaining combinations with Red &Metal or Yellow & Metal, so pleasereport these immediately if you see one!We are keen to enlist the help ofmore ringers, so please get in touch ifyou have a site where you can catchwintering Blackcaps, and we will supplyrecording details and colour rings.Contacts: Benjamin Van Doren(benjamin.vandoren@zoo.ox.ac.uk),Greg Conway (greg.conway@bto.org)INTERREXInterrex have recently been experiencingissues with communications which mayhave led to delays in ring production orfailure to deliver goods after paymenthas been taken. They have requestedthat anyone who needs an update ontheir order, or wishes to claim a refund,gets in touch at: shop@interrex.plLIFECYCLE – 3

Blue Tit, by Sarah Kelman/BTOFIELDWORK Moult projectThe sheer volume of data collected each year across a wide range of habitats and latitudes makes Blue Tit the perfect model species forstudies of environmental impacts such as climate and land-use change.Do you ring Blue Tits?If so, you have made a good start towards taking part in our new project, explain David Norman and Dave Leech. TheBlue Tit is much maligned due to its ubiquitous nature and aggressive temperament, but the former quality is actuallya real strength. The Blue Tit demographic datasets are some of the most utilised on an annual basis, so your recordsreally are put to good use straight away.WHAT’S THE POINT OF THIS STUDY?OTHER SPECIESHaving trialled theprotocol on Blue Tit,the aspiration is tocycle through otherspecies in futureyears, with GreatTit, Blackbird, Robin,Goldfinch, Chaffinchand Siskin all potentialcontenders. If youalready have dataon p-j moult, havesuggestions for anotherstudy species orwould like to help withcoordination of futureprojects, please contactruth.walker@bto.org4 – LIFECYCLEOne aspect of the annual cycle that is stillrelatively poorly understood for the majorityof bird species is moult, yet this neglectbelies its importance. Replacing feathersis expensive and time-consuming but thebenefits in terms of insulation and flightefficiency are likely to be great, creating thepotential for significant trade-offs betweenmoulting, breeding and surviving. Postjuvenile (p-j) moult may play a particularlyimportant role in determining which birdsmake it through the winter, where they goand whether they find a mate.Blue Tits are ideally placed to furtherour knowledge in this respect, and not justbecause they are caught in large numbersat many locations. In most individuals, it isrelatively easy to see the extent of p-j moult,distinguishing the retained (old) feathersgrown in the nest from those grown in themoult. In addition, the species is almostexclusively single brooded, so there can beno confusion caused by differential degreesof feather replacement exhibited by firstyear birds of different ages.The extent of p-j moult is thought to bea measure of the quality of the bird, eitherdirectly in terms of condition, or indirectlyin terms of fledging date, with later-fledgedindividuals typically less likely to recruitinto the population. The intention of thisstudy is to ask as many ringers as possibleto record details of the partial p-j moult inbirds of age code 3 (in November) and age 5(in February) to see if the mean number ofreplaced feathers changes during the winter.The working hypothesis is that weaker birds,assumed to be those with less extensive p-jmoult, are less likely to survive the winter,and thus this mean number will increasebetween sampling periods.With data from a large range of sites, weshall also be able to explore spatial variationin the extent of moult, analysing data byregion and habitat. By repeating the projectevery few years, perhaps on a five-year cycle,we may be able to identify temporal trends.WHAT DATA DO I NEED TO COLLECT?Data are welcomed from any site where youcan catch reasonable samples of Blue Tits –garden, woodland, feeding station – usingany method, including mist-net, traps,whoosh net, etc, provided that the same siteand methods are used in both NovemberAutumn 2018

Moult project FIELDWORKand February. You can register more thanone site provided that the data from eachare distinguishable. For every Blue Tit aged3 encountered in November 2018 or aged5 encountered in February 2019, we wouldlike you to record the moult extent (numberof retained juvenile feathers) in the greatercoverts (OGCs) and alula, along with thewing length and weight (see RecordingProtocol). We would also be interested inreceiving data on tail and tertial moult,from those confident in collecting thisinformation and inputting it into DemOn/ IPMR. If you already hold such data fromthe same sites in previous years, we wouldbe very pleased to hear from you.HOW DO I TAKE PART?Recording protocolEveryone who ages Blue Tits should normally be looking for old greatercoverts or moulted alula feathers; all that we are asking is for ringers torecord these data and, optionally, any moulted tertials or tail feathers.i) Please consistently record the same wing for each bird; some haveasymmetric moult, usually differing by one feather between the two wings.Be careful not to bias the data by recording, for instance, the wing withmore OGCs; always record whichever wing you normally examine for everybird.ii) In DemOn, the fields you will need to record the data are Alula Scoreand Old Greater Coverts. In IPMR, the fields are OGCMoultScore andAlulaMoultScore. These can be added to your standard inputting fieldsetup or, in DemOn, you will be able to use a custom field setup createdspecifically for the project. Both of these fields require only a single numberto be entered (remember to record zeros where appropriate).iii) If also recording tail and tertials, you will need to complete the TailMoult Scores and Secondary Moult Score fields (or L Tail Moult Scores /L Secondary Moult Score depending which side of the bird you usuallyexamine). These fields are derived from the moult card, so each tail featheror tertial should be recorded as 0 for old or 5 for replaced. For example, theright-half of the tail of the bird below will be scored 500000.More details will be provided in the guidance material sent once you haveregistered.Blue Tit wing and tail, by David NormanThe lead author of this article hasvolunteered to coordinate the field aspectof this study. Anyone wishing to take partwill need to register with David Norman byemailing partmoult@gmail.com. Data canbe recorded and submitted using existingfields in IPMR or DemOn (see RecordingProtocol. To be able to extract the data, ifyou are using IPMR we will need to knowthe permit number associated with theringer, the rings used (if different) and therelevant Places and (if relevant) Sub-siteCode(s); if you are using DemOn, we willneed to know the Username of the accountyou are inputting data through (i.e. whoyou are Operating As) and the relevantLocation Code(s). Once registered, youcan submit your data as normal and wewill be able to extract it from the databaseat BTO HQ. Once all the data have beencollated, analyses will be undertaken by theproject coordinator in collaboration withBTO staff, the end product either being aLifeCycle article or a Ringing & Migrationpaper, depending on the uptake and results.Juvenile Blue Tit wing showing three old greater coverts and unmoulted alula feathers but one moulted tertial feather. The two centralrectrices in this juvenile tail have been moulted and are bluer and more rounded than the unmoulted feathers.Autumn 2018LIFECYCLE – 5

Woodpigeon, by Mike Weston/BTOMONITORING WoodpigeonsWoodpigeon nests often seem to be built in exactly the same place from year to year, so it is always worth checking nest sites fromprevious seasons.Woodpigeons: better late than neverWhile the nesting season is over by mid to late summer for most nest recorders, Paul Slater has found a way toextend his season. Since 1994, Paul has studied the Woodpigeons nesting in suburban Liverpool, predominantlyat Sefton Park, a large Victorian recreation ground of 100 hectares. He completes over 100 nest record cards forWoodpigeons each year and rings about 100 nestlings. In this article, he reflects on the findings of his 25-year study.Woodpigeons have a much later breedingseason than most other species of bird.Although some breed quite early, most ofthe population that I study do not startnesting until later in the year, the majoritybetween July and September. This ispossibly because the young birds are mainlyreared on ripening and ripe seeds, collectedby the adults and regurgitated to the young,which become abundant at the end of thesummer. In this and other studies, suchas those carried out by Ron Murton whileworking for the Ministry of Agriculture,Fisheries and Food in the 1950s and 1960s,the main food fed to chicks at this timeof year is seed such as wheat, barley andoilseed rape. Consequently, whereas manynest recorders will be most active earlier inthe year, the majority of my nest findingand monitoring takes place much later inthe season, and continues through untilautumn.NEST FINDINGMy methodology for finding nests consistsof systematic cold searching. Although birdscan often be observed building, some ofthese attempts do not come to anything,6 – LIFECYCLEwith nests not completed or no eggs beinglaid. In addition, some Woodpigeonsengage in pseudo-incubation, wherebirds sit on completed, empty nests forlengthy periods of time before any eggsare laid. If birds are observed building, anote is made of the nest location and, ifthe attempt gives rise to an occupied nest,this is subsequently checked when theopportunity arises.Most nests are found by walkingaround and below the canopies of trees,scanning them with binoculars. In mysuburban study, I have found lime to bethe favoured tree to breed in, followed byholly and then beech. All accessible treesare thoroughly scanned, even those withvery open canopies, such as planes andsycamores.When a nest is located, a note is madeof the species of tree, approximate heightabove ground level and its whereabouts inthe park. Sometimes nests are built on old(or even active) Grey Squirrel dreys, or onthe old nests of other bird species; birdssitting on these nests can be difficult tosee, so I pay particular attention to thesestructures.Autumn 2018

Woodpigeons MONITORINGMost of my searching is carried out in themorning, with any climbing taking placeas early as is practicable so as not to drawany unwanted attention and in order tominimise disturbance. In recent years,some members of the public visiting SeftonPark have taken to feeding Magpies andCarrion Crows and, as a consequence,they associate people with food. If thesepotential predators are present close toa nest site, then I wait for them to moveaway or I move on myself, returning later.Whether this supplementary feeding ofcorvids is affecting the breeding successof Woodpigeons in the park has yet tobe determined; however, in areas wherethis feeding takes place, sites whereWoodpigeons used to nest regularly arenow avoided.Tolerance of human presence, and thefact that nests can be closely observed fromthe ground, makes repeat checks of nestspossible without disturbing the birds. Thesechecks have provided evidence that somelarge young disappear before they couldhave fledged and searches of the area haveoccasionally found their predated remainsnearby.RINGING PULLIThe most suitable time to ring Woodpigeonpulli is when they are between 10 and14 days old, when feathers are small tomedium in NRS parlance. The legs of pullithat are younger than this are unlikely tobe developed enough to take a ring andpulli older than this may try to fledgeprematurely and are also more difficult tohandle. It is worth noting that single chicksgrow faster than two chicks, and if foodsupplies are plentiful, the chicks will alsogrow more quickly. Chicks can be ringed inthe canopy, at or near the nest, providingthere is a suitable, safe position to do so.If a nest holds more than one chick,then I will ring one, place it back on thenest and then ring the second, rather thanremoving both simultaneously. At theoptimum age, the chicks stay put on thenest; although they may inflate themselves,lunge at you with their beaks or flap theirwings, they will not leave the platform.Older nestlings can be handled by placing acloth bag over the nest, removing the birdsfor ringing, then replacing them under thebag; the bag can be removed after severalminutes, if possible after one has moved toa position just below the nest. If the younglook to be older than about 16 days, thenI do not climb and just make observationsfrom the ground.When handling young Woodpigeons,it is essential that nestlings are kept uprightat all times to prevent them inhalingregurgitated milk from the crop. Chicksshould not be held in the ringers’ grip,which can put pressure on the crop, butinstead should be cradled in the hand,with the breast towards the palm and feetbetween the fingers, without placing anypressure on the tracheal region.BRANCHINGAt the heightof the breedingseason, when theadults have accessto plentiful, highquality foods, theyoung can havea very fast rate ofgrowth. In treesthat are strongenough to taketheir weight, somebirds can leave thenest as early as 18days old. Althoughthey do not movefar at first, usuallymoving ontonearby branches,some birds canmove high intothe canopy of thenest tree, or intothe canopies ofadjacent trees,where theycontinue to be fedby the adults. Thisshould be bornein mind whenmaking returnvisits to assess thebreeding outcome.Woodpigeon nest with chick, by Chris & Elspeth Rowe/BTOTIMINGMonitoringWoodpigeons may not be an obvious priority for monitoring as they are soubiquitous but there are many interesting aspects of their ecology to explore. Thepopulation is growing rapidly, with a 450% rise in numbers since the mid-1960s,but has this increase been driven by changes in productivity or survival? They areexpanding quickly into urban habitats; does this affect their nesting phenology orsuccess? What are the impacts on potential competitors, such as Collared Dove, andpredators, such as Sparrowhawk? To what extent are they implicated in the spread oftrichomonosis?With so many questions, it is important to collect as much data as we can.Breeding attempts are easy to find and monitor, yet we only receive c. 700 nestrecords a year and fewer than 300 pulli are ringed annually. So if you do find aWoodpigeon nest at any time of year, please collect the relevant data – nothing isever too common to monitor.Autumn 2018LIFECYCLE – 7

MONITORING WoodpigeonsCatching adults for RASAnother issue that anyone handlingchicks should be aware of is that duringhot weather, some nestlings can be hostto flatflies (also called louse flies or keds).Occasionally, these can transfer themselvesto the observer at the nest. Althoughthese insects are entirely harmless tohumans, some people find them revolting,particularly the way they can take refugeamongst your clothing; when they realisethat the conditions are not suitable forthem, they usually move on!TIME MANAGEMENTWhen there are a lot of nests on thego, it is important to have good recordmaintenance; at busy times of the year,such as during August, I can potentiallybe ringing nestling Woodpigeons everyday. By early October most birds havefinished nesting, although there will stillbe some nests holding young. Althoughtime-consuming, I find searching forWoodpigeon nests very pleasurable andrewarding.Woodpigeon: nest-recording profileResident. Ubiquitous (bar bare uplands): mostly in farmland, woods and open scrub with scattered bushes; even on treelessheathery islands (Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland) and rocky hillsides. Increasing in towns/villages, where nesting starts significantlyearlier. Usually solitary, but semi-social in optimum habitats. Site: In tree, bush or hedge up to 25 m, usually at 3–5 m on spreadingbough or close to trunk; evergreens preferred early in season; later, broadleafs, especially bushes, also honeysuckle and otherclimbers; sometimes on ground in heather (Scottish islands), hedge bottoms, even crops or marram, or on building ledge or otherartefact.Nest: Flimsy platform of twigs, lined rootlets, grass and straw, but, if reused for another brood or in a subsequent season, becomesmore solid; ground nests involve only lining. May use old stick nest as foundation or evict smaller species e.g. Collared Dove.Broods: 2–3. Eggs: 2 (1–2). Incubation: 15–18. Hatching to fledging: 29–35 days.JFMAMJJASONDEggsYoungNest-finding tips: Territory indicated by cooing, notably in mornings and mid/lateafternoons, and by male display flights. Pairs perch near chosen sites. Male collectingtwigs easily watched back. Nests found by walking under spreading trees or along hedgesagainst light. Adults can be seen sitting tightly at later egg and small-young stage; at othertimes, they crash off with loud clatter.8 – LIFECYCLEAutumn 2018Text adapted from BTO’s Field Guide to Monitoring Nests. Woodpigeon nest, by Chris & Elspeth Rowe/BTOWoodpigeon is, in some ways, an ideal species for RAS. They are not toodifficult to catch, and are quite visible, making it relatively easy to readcolour marks. Currently, there is only one RAS project on Woodpigeon,run by Lee Barber in his garden here in Thetford. Here, he provides someadvice on catching adult birds.Adults can be caught in Potter traps or large drop traps throughoutthe year, although they tend to visit the garden less at harvest time.Woodpigeons are strong birds that can flap when caught, potentiallyknocking traps over, so, if catching on a bird table it is advisable to fix thetrap to the table to prevent it being knocked to the floor. Woodpigeonsprefer to land and walk into traps, so placing the trap on a large birdtable will make them more likely to use it. Baiting the trap with wheat willattract Woodpigeons but, if expense is not an issue, sunflower hearts arepreferred; mixing the two together can help to lessen the financial burden!If traps are placed on the ground, siting them underneath sunflower-heartfeeders will help to bait the trap with seed dropped by the feeding birds.Woodpigeons have an adult survival rate of c. 60%, although in anurban setting, predation by cats might reduce this figure. A successful RASproject will therefore require approximately 60 adult birds to be caughteach year to stand a chance of re-encountering 30 of these the followingyear. This presumes that 80% of the marked population can be reencountered each year; if fewer are re-encountered, the marked populationwill need to be larger. If you are interested in starting a Woodpigeon RAS,please get in touch with Ruth Walker at ras@bto.org

Ringing Committee update COMMUNITYEllen Marshall, by John ClarkT- and C-permit holder reps on RINThis autumn, we will be lookingfor candidates, nominated by theirtrainer, to fill the T- and C-permitrepresentative positions on RingingCommittee (RIN). We could notthink of a better advert for the rolesthan to ask one of the existingrepresentatives to say what theythought of their term on theCommittee. Ellen Marshall, ourcurrent T representative, has donejust that, so read on.In 2015, my ringing group at TreswellWood, Nottingham, suggested that Iput myself forward for the advertisedposition of Trainee Representative onthe Ringing Committee at the BTO. Atthe time, I had only been ringing for ayear, and so the prospect of attendingmeetings with very experienced andknowledgeable ringers was quitedaunting! I was quite unsure what, ifanything, I would be able to contributeto these meetings, and prior to the firstmeeting I was extremely nervous. I amhappy to say that I was wrong to beunsure and anxious, and was instantlywelcomed to the Committee by allmembers. I have now attended the biannual meetings for the last three years,and have thoroughly enjoyed each ofthem.I must admit that prior to attendingthe meetings, I had absolutely noknowledge of RIN, of the peoplewho were essential to it, and the workthat they did. As a new trainee, myknowledge of the Scheme ran to whatrelevant information I had read in theRingers’ Manual, what was in my traineepack, and information about the birdsthemselves. The inner workings of theRinging Scheme were a mystery tome, and so when I attended the firstmeeting, it was quite an eye-openingAutumn 2018experience to discover all the hard workthat goes on behind the scenes.I was encouraged from the start tocontribute and have my input, and Ioften found that my comparative lackof experience was beneficial in thatI was able to approach issues froman outside perspective and give theopinion of a new trainee. This camein particularly useful during a recentreview of training, where I was able tocontribute ideas to refine the trainingprocess and information suppliedto new starting trainees. Throughdiscussions of issues such as this, I havegained a lot of new knowledge. Beinga part of RIN has given me a new andimproved perspective on the RingingScheme and helped me to understandthe importance of my own

THE BTO MAGAZINE FOR RINGERS AND NEST RECORDERS . The Ringing and Nest Record schemes . of over 25 ringers across Britain and Ireland. The colour ringing is allowing us to build up a very detailed picture . benjamin.vandoren@zoo