Transcription

Hermann Hesse’sSiddharthaAn Open Source ReaderEdited byLee ArchieJohn G. Archie

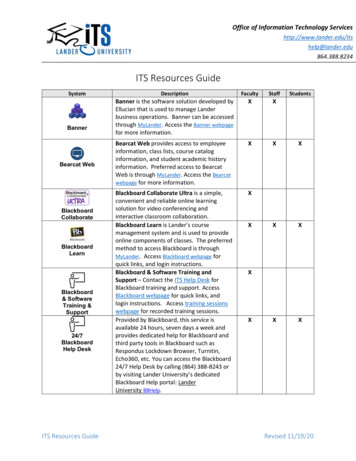

Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha: An Open Source ReaderEdited by Lee Archie and John G. ArchieVersion 1.0 EditionPublished January, 2006Copyright 2006 License GFDL Lee Archie, John G. ArchieComments. Michael Pullen originally produced the e-book for ProjectGutenberg upon which this open source text is based. Translations were made byGunther Olesch, Anke Dreher, Amy Coulter, Stefan Langer, SemyonChaichenets, and proofreading was done by Chandra Yenco and Isaac Jones.Changes made to the text by the editors of the current GFDL version aregrammatical and typographical changes together with the addition of images, anindex, and questions at the beginning and end of each chapter.GNU Free Documentation License. The collaborators would be grateful forcorrections or other suggestions to this preliminary draft. Please addresscomments tophilbook@philosophy.lander.eduPermission is granted to copy, distribute, and/or modify this document under theterms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version,published by the Free Software Foundation, with no Invariant Sections, noFront-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is available atthe GNU Free Documentation License (http://gnu.org/copyleft) Website.Image Credits. Image Credits The following images have been determined to beof fair use or in the public domain.The Gardens of Delhi gardens.html). ShishirThadani. [Ch. 4] Jayanti Park 3 [Ch. 5] Jayanti Park 1.GNU Free Documentation License (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html). GNU Philosophical Gnu.Image India (http://members.tripod.com/image india/). Shishir Thadani. [Ch. 10] Palace Jaali,Govind Mandir Palace [Ch. 11] The Banks on the Ganges in Patna [Ch. 12] Spring in Bhimtal; AtMonsoon Palace, Deegh, Rajasthan.IronOrchid PhotoClipart (http://www.ironorchid.com/clipart/). Antiquities Project. [Ch. 4] BuddhaPlate; Country Scene.Library of Congress (http://lcweb2.loc.gov). P&P Online Catalog. [Pt. I] Buddha PreachingLC-USZ62-111688 [Ch. 1] Priest Sitting LC-USZ62-34390; [Ch. 2} Transportation (detail)LC-USZ62-35010 [Ch. 3] Buddha Preaching LC-USZ62-111688; Palace in Amber LC-USZ61-949;Well of Knowledge LC-D426-554 [Ch.5] Children of the Workers of the Firewood SectionLC-USW33- 043060-ZC [Ch. 6] Official, India LC-USZ62-91594; Parsee WeddingLC-USZ62-91595; Natch Girl Dancing LC-USZ62-35125 [Ch. 7] View of Birdcages (detail)LC-USZ62-81246 [Ch. 8] Hyderabad Colonnade LC-D41-149; Bridge over the RungrooLC-USZ62-76815 [Ch. 9] A Stream in India LC-USW33-043090-ZC; Riverscene W7-589 [Ch. 10]

Portrait of Hindu Musician (detail) LOT 12735, no. 511 [Ch. 11] Buddha Figure LC-USZ62-116439[Ch. 12] India’s Sacred Lotus LC-USZ62-71354.Metropolitan Museum of Art (http://www.metmuseum.org/) Standing Buddha, Gupta period (ca.319?500), 5th century, Uttar Pradesh, Mathura, India, Enid A. Haupt Gift.NOAA Photo Library (http://www.photolib.noaa.gov/). Historic C&GS Collection,. [Forward] TabulaeRudolphinae : quibus astronomicae. . . by Johannes Kepler, 1571-1630 [Ch. 9] Eddies (detail)theb2710.University of Minnesota Libraries (http://ames.lib.umn.edu/diguide.phtml). Underwood andUnderwood. [Ch. 2] Fakirs at Amritsar.World Art Kiosk (http://worldart.sjsu.edu/). California State University. [ch.5] Kama: God of Love,Seattle Museum Kathleen Cohen [Ch. 8] Assault of Mara, Guimet Museum, Paris KathleenCohen.Non-U.S. Copyright Status. Status of text and images in this publication:All text and images in this work are believed to be in the public domain or are published here underthe fair use provision of the US copyright law. Responsibility for making an independent legalassessment of an item and securing any necessary permission ultimately rests with anyone desiring toreuse the item under to GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html). The written permission of thecopyright owners and/or other rights holders (such as publicity and/or privacy rights) is required fordistribution, reproduction, or other use of protected items beyond that allowed by fair use or otherstatutory exemptions. An independent legal assessment has been made after a search for copyrightstatus of text and images. No representation as to copyright status outside the United States is made. Ifan error occurs in spite of the good faith efforts, the offending item will be removed upon notice tophilbook@philosophy.lander.eduThe U.S. Copyright Office (http://www.loc.gov/copyright/) Circular 22 points out, “Even if youconclude that a work is in the public domain in the United States, this does not necessarily mean thatyou are free to use it in other countries. Every nation has its own laws governing the length and scopeof copyright protection, and these are applicable to uses of the work within that nation’s borders.Thus, the expiration or loss of copyright protection in the United States may still leave the work fullyprotected against unauthorized use in other countries.”DocBook—. And related topics.This publication is based on Open Source DocBook, a system of writing structured documents usingSGML or XML in a presentation-neutral form using free programs. The functionality of Docbook issuch that the same file can be published on the Web, printed as a stand-alone report, reprinted as partof a journal, processed into an audio file, changed into Braille, or converted to most other media types.More information about DocBook can be found at DocBook Open Repository(http://docbook.sourceforge.net). Information concerning the processing of this book is in theColophon.

Table of ContentsForward . iWhy Open Source?. iPart I. . i1. The Son of the Brahmin . 1Ideas of Interest from “The Son of the Brahmin”. 1The Reading Selection from “The Son of the Brahmin” . 2Topics Worth Investigating . 82. With the Samanas. 11Ideas of Interest from “With the Samanas” . 11The Reading Selection from “With the Samanas” . 12Topics Worth Investigating . 193. Gotama . 22Ideas of Interest from “Gotama”. 22The Reading Selection from “Gotama”. 23Topics Worth Investigating . 304. Awakening . 32Ideas of Interest from “Awakening” . 32The Reading Selection from “Awakening”. 33Topics Worth Investigating . 37Part II. . 405. Kamala. 41Ideas of Interest from “Kamala”. 41The Reading Selection from “Kamala” . 42Topics Worth Investigating . 536. With the Childlike People. 55Ideas of Interest from “With the Childlike People”. 55The Reading Selection from “With the Childlike People” . 56Topics Worth Investigating . 647. Sansara . 66Ideas of Interest from “Sansara” . 66The Reading Selection from “Sansara” . 67Topics Worth Investigating . 738. By the River. 75Ideas of Interest from “By the River” . 75The Reading Selection from “By the River” . 76Topics Worth Investigating . 849. The Ferryman . 86Ideas of Interest from “The Ferryman” . 86The Reading Selection from “The Ferryman”. 87Topics Worth Investigating . 9710. The Son. 99Ideas of Interest from “The Son”. 99iv

The Reading Selection from “The Son” . 100Topics Worth Investigating . 10711. Om . 109Ideas of Interest from “Om” . 109The Reading Selection from “Om”. 110Topics Worth Investigating . 11512. Govinda . 117Ideas of Interest from “Govinda”. 117The Reading Selection from “Govinda”. 118Topics Worth Investigating . 126Index . 129Colophon . 132Siddhartha: An Open-Source Textv

ForwardTabulae Rudolphinae : quibus astronomicae. . . by Johannes Kepler, 15711630, NOAAWhy Open Source?Many works in philosophy and literature are accessible via online sources onthe Internet. Fortunately, much of the best work in philosophy and literature isavailable in the public domain. A translation of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha,in particular, became available through Project Gutenberg by Michael Pullen.This edited version of that text is subject to the legal notice following the titlepage referencing the “GFDL License.”Since the edited text is placed under the GFDL, this work is open-sourced,in part, to minimize costs to interested students of philosophy and, in part, tomake it widely available in a form convenient to a wide variety of readers.A particular virtue of the DocBook method of publishing used here is thepracticable conversion of the source files into a variety of formats, includingaudio and Braille. Moreover, readers, themselves, can improve the product ifthey wish to do so.This particular edition represents the first stable version in the developmentof the open-source text. The development model of Siddhartha is looselypatterned on the “release early, release often” model championed by Eric S.i

ForwardRaymond.1 Various formats of this work are being made available for distribution. If the core reading and commentary prove useful, the successiverevisions will be released as incrementally numbered “stable” versions beyond version 1.0. Our publication is based on Open Source DocBook, a system of writing structured documents using SGML or XML in a presentationneutral form using open source programs. The functionality of DocBook issuch that the same file can be published on the Web, printed as a standalonereport, reprinted as part of a journal, processed into an audio file, changedinto Braille, or converted to most other media types. If the core readingsand commentary prove useful, successive revisions, readings, commentaries,and other improvements by users can be released in incrementally numbered“stable” versions.Several sources on the Internet deserve special mention for authoritative andinsightful analysis and commentary on philosophy. Readers who wish to beconversant fully with the philosophical ideas will wish to consult the following e-texts.1. Dictionary of the History of Ideas.2 Studies of Selected Pivotal Ideas,edited by Philip P. Wiener, was published by Charles Scribner’s Sons,New York, in 1973-74. Now out of print, the Dictionary is publishedonline with the help of Scribner’s and the Electric Text Center at theUniversity of Virginia. The Dictionary includes articles on the historical development of a broad spectrum of ideas in philosophy, religion,politics, literature, and the biological, physical, and social sciences.2. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.3 This site (subtitled "A FieldGuide to the Nomenclature of Philosophy") consists of regularly updatedoriginal articles by fifteen editors, one hundred academic specialists,and technical advisors. The articles are authoritative, peer-reviewed, andavailable for personal and classroom use. The general editors are JamesFieser and Bradley Dowden. The site is most useful for students in obtaining secondary source information on the key terms and personagesof philosophy. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy can also be recommended for obtaining an overview of the problems of philosophy forbackground readings for lectures and papers. In general, the articles arewell researched and are accessible by undergraduates.3. The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory & Criticism.4 The electronic version of the well-known guide to literary theory has hyperlinked cross-references, names, topics, and subject entries as well as full1. Eric Raymond. The Cathedral and the Bazaar. Sebastopol, CA:O’Reilly & Associates, 1999. Online at The Cathedral and the Bazaar(http://www.catb.org/ esr/writings/cathedral-bazaar/).2. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/DicHist/dict.html3. http://www.iep.utm.edu/4. http://www.press.jhu.edu/books/hopkins guide to literary theory/g-contents.htmliiSiddhartha: An Open-Source Text

Forwardtext search capability. The work, edited by Michael Groden and Martin Kreiswirth, includes references to the social and physical sciences aswell as connections to historical, philosophical, and cultural theories.4. Meta-Encyclopedia of Philosophy.5 A dynamic resite by Andrew Chruckyaccesses the following sources: Dagobert D. Runes (ed.), Dictionary ofPhilosophy, 1942, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Dictionary of the Philosophy of Mind, The IsmBook, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), and A Dictionary of Philosophical Terms and Names.5. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.6 This continuously updated reference work is a publishing project of the Metaphysics Research Lab atthe Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI) at StanfordUniversity. The general editor of the Stanford Encyclopedia is Edward N.Zalta. Authors of subject entries are well-known scholars in their fields;even so, the subjects discussed are authoritative and well balanced. TheEncyclopedia is the most scholarly general source for philosophy on theInternet and is essential as a starting point and background research forphilosophy term papers.6. Thoemmes Encyclopedia.7 Biographical and bibliographical database including major figures in the history of ideas has a search function as wellas a list of key personages. Thoemmes Press (pronounced as "Thomas")originated from Thoemmes Antiquarian Books and specializes in publishing the scholars of intellectual history. The biographical sources onthis site are authoritative, accurate, and helpful background summariesof the life and thought of important figures in the Western intellectualtradition.7. The 1911 Edition Encyclopedia.8 The 11th Edition of the EncyclopediaBritannica contains articles from experts in their fields is still a widelyused reference and a classic resource for the state of knowledge in 1911.Our first consideration for this book is to make primary sources accessibleto a wide variety of readers—including readers curious about the subjectspresented, readers with disabilities, readers in developing countries, as wellas college, high school, and home schooling students on a budget.Please send your questions and inquiries of interest to the “Editors” at philbook@philosophy.lander.edu org/Siddhartha: An Open-Source Textiii

Part I.Discovering the Unseen (or lesser known) Heritage, Image-India, ShishirThadani

Chapter1The Son of the BrahminPriest Sitting, Library of CongressFrom the reading. . .“But where, where was this self, this innermost part, this ultimate part?It was not flesh and bone, it was neither thought nor consciousness,thus the wisest ones taught. So, where, where was it?”Ideas of Interest from “The Son of theBrahmin”1. Why did Siddhartha remain standing when his father requested that therebe no more discussion of joining the ascetics? Why didn’t Siddharthajust leave as he had promised Govinda? Explain why Siddhartha’s father1

Chapter 1. The Son of the Brahmin“allowed him” to leave. Speculate in what way Siddhartha’s father cameto his decision.2. Siddhartha had always obeyed his father’s wishes. Conjecture what hewould have done if his father had said “No” to his request to leave andjoin the Samanas.3. Why does Siddhartha speak of himself in the “third person”? Try speaking of yourself in the third person for a short time in order to see theeffects of this technique.4. Given that Govinda was Siddhartha’s “spear carrier,” envision the conditions under which Govinda left home. How do you suspect that Siddhartha’s and Govinda’s parents differ in their practices of child rearing?The Reading Selection from “The Sonof the Brahmin”In the shade of the house, in the sunshine of the riverbank near the boats,in the shade of the Sal-wood forest, in the shade of the fig tree is whereSiddhartha grew up, the handsome son of the Brahmin, the young falcon, together with his friend Govinda, son of a Brahmin. The sun tanned his lightshoulders by the banks of the river when bathing, performing the sacred ablutions, the sacred offerings. In the mango grove, shade poured into his blackeyes, when playing as a boy, when his mother sang, when the sacred offerings were made, when his father, the scholar, taught him, when the wise mentalked. For a long time, Siddhartha had been partaking in the discussions ofthe wise men, practising debate with Govinda, practising with Govinda theart of reflection, the service of meditation. He already knew how to speak theOm silently, the word of words, to speak it silently into himself while inhaling, to speak it silently out of himself while exhaling, with all the concentration of his soul, the forehead surrounded by the glow of the clear-thinkingspirit. He already knew to feel Atman in the depths of his being, indestructible, one with the universe.Joy leapt in his father’s heart for his son who was quick to learn, thirsty forknowledge; he saw him growing up to become a great wise man and priest, aprince among the Brahmins.Bliss leapt in his mother’s breast when she saw him, when she saw him walking, when she saw him sit down and get up, Siddhartha, strong, handsome,he who was walking on slender legs, greeting her with perfect respect.Love touched the hearts of the Brahmins’ young daughters when Siddharthawalked through the lanes of the town with the luminous forehead, with theeye of a king, with his slim hips.2Siddhartha: An Open-Source Text

Chapter 1. The Son of the BrahminBut more than all the others he was loved by Govinda, his friend, the sonof a Brahmin. He loved Siddhartha’s eye and sweet voice, he loved his walkand the perfect decency of his movements, he loved everything Siddharthadid and said and what he loved most was his spirit, his transcendent, fierythoughts, his ardent will, his high calling. Govinda knew: he would not become a common Brahmin, not a lazy official in charge of offerings; not agreedy merchant with magic spells; not a vain, vacuous speaker; not a mean,deceitful priest; and also not a decent, stupid sheep in the herd of the many.No, and he, Govinda, as well did not want to become one of those, not oneof those tens of thousands of Brahmins. He wanted to follow Siddhartha, thebeloved, the splendid. And in days to come, when Siddhartha would becomea god, when he would join the glorious, then Govinda wanted to follow himas his friend, his companion, his servant, his spear-carrier, his shadow.Siddhartha was thus loved by everyone. He was a source of joy for everybody,he was a delight for them all.From the reading. . .“Your soul is the whole world.”But he, Siddhartha, was not a source of joy for himself, he found no delightin himself. Walking the rosy paths of the fig tree garden, sitting in the bluishshade of the grove of contemplation, washing his limbs daily in the bath ofrepentance, sacrificing in the dim shade of the mango forest, his gestures ofperfect decency, everyone’s love and joy, he still lacked all joy in his heart.Dreams and restless thoughts came into his mind, flowing from the water ofthe river, sparkling from the stars of the night, melting from the beams ofthe sun, dreams came to him and a restlessness of the soul, fuming from thesacrifices, breathing forth from the verses of the Rig-Veda, being infused intohim, drop by drop, from the teachings of the old Brahmins.Siddhartha had started to nurse discontent in himself, had started to feel thatthe love of his father and the love of his mother, and also the love of hisfriend, Govinda, would not bring him joy for ever and ever, would not nursehim, feed him, satisfy him. He had started to suspect that his venerable fatherand his other teachers, that the wise Brahmins had already revealed to himthe most and best of their wisdom, that they had already filled his expectingvessel with their richness, and the vessel was not full, the spirit was not content, the soul was not calm, the heart was not satisfied. The ablutions weregood, but they were water, they did not wash off the sin, they did not heal thespirit’s thirst, they did not relieve the fear in his heart. The sacrifices and theinvocation of the gods were excellent—but were that all? Did the sacrificesgive a happy fortune? And what about the gods? Was it really Prajapati whohad created the world? Was it not the Atman, He, the only one, the singularSiddhartha: An Open-Source Text3

Chapter 1. The Son of the Brahminone? Were the gods not creations, created like you and I, subject to time,mortal? Was it therefore good, was it right, was it meaningful and the highest occupation to make offerings to the gods? For who else were offerings tobe made, who else was to be worshipped but Him, the only one, the Atman?And where was Atman to be found, where did He reside, where did his eternalheart beat, where else but in one’s own self, in its innermost part, in its indestructible part, which everyone had in himself? But where, where was thisself, this innermost part, this ultimate part? It was not flesh and bone, it wasneither thought nor consciousness, thus the wisest ones taught. So, where,where was it? To reach this place, the self, myself, the Atman, there was another way, which was worthwhile looking for? Alas, and nobody showed thisway, nobody knew it, not the father, and not the teachers and wise men, notthe holy sacrificial songs! They knew everything, the Brahmin and their holybooks, they knew everything, they had taken care of everything and of morethan everything, the creation of the world, the origin of speech, of food, ofinhaling, of exhaling, the arrangement of the senses, the acts of the gods, theyknew infinitely much—but was it valuable to know all of this, not knowingthat one and only thing, the most important thing, the solely important thing?Surely, many verses of the holy books, particularly in the Upanishads ofSamaveda, spoke of this innermost and ultimate thing, wonderful verses.“Your soul is the whole world,” was written there, and it was written that manin his sleep, in his deep sleep, would meet with his innermost part and wouldreside in the Atman. Marvellous wisdom was in these verses, all knowledgeof the wisest ones had been collected here in magic words, pure as honey collected by bees. No, not to be looked down upon was the tremendous amountof enlightenment which lay here collected and preserved by innumerable generations of wise Brahmin.—But where were the Brahmin, where the priests,where the wise men or penitents, who had succeeded in not just knowing thisdeepest of all knowledge but also to live it? Where was the knowledgeableone who wove his spell to bring his familiarity with the Atman out of thesleep into the state of being awake, into the life, into every step of the way,into word and deed? Siddhartha knew many venerable Brahmins, chiefly hisfather, the pure one, the scholar, the most venerable one. His father was tobe admired, quiet and noble were his manners, pure his life, wise his words,delicate and noble thoughts lived behind its brow —but even he, who knewso much, did he live in blissfulness, did he have peace, was he not also just asearching man, a thirsty man? Did he not, again and again, have to drink fromholy sources, as a thirsty man, from the offerings, from the books, from thedisputes of the Brahmin? Why did he, the irreproachable one, have to washoff sins every day, strive for a cleansing every day, over and over every day?Was not Atman in him, did not the pristine source spring from his heart? Ithad to be found, the pristine source in one’s own self, it had to be possessed!Everything else was searching, was a detour, was getting lost.Thus were Siddhartha’s thoughts, this was his thirst, this was his suffering.4Siddhartha: An Open-Source Text

Chapter 1. The Son of the BrahminOften he spoke to himself from a Chandogya-Upanishad the words, “Truly,the name of the Brahman is satya—verily, he who knows such a thing, willenter the heavenly world every day.” Often, it seemed near, the heavenlyworld, but never he had reached it completely, never he had quenched theultimate thirst. And among all the wise and wisest men, he knew and whoseinstructions he had received, among all of them there was no one, who hadreached it completely, the heavenly world, who had quenched it completely,the eternal thirst.“Govinda,” Siddhartha spoke to his friend, “Govinda, my dear, come withme under the Banyan tree, let’s practise meditation.”They went to the Banyan tree, they sat down, Siddhartha right here, Govindatwenty paces away. While putting himself down, ready to speak the Om, Siddhartha repeated murmuring the verse:Om is the bow, the arrow is soul,The Brahman is the arrow’s target,That one should incessantly hit.After the usual time of the exercise in meditation had passed, Govinda rose.The evening had come, it was time to perform the evening’s ablution. Hecalled Siddhartha’s name. Siddhartha did not answer. Siddhartha sat therelost in thought, his eyes were rigidly focused towards a very distant target,the tip of his tongue was protruding a little between the teeth, he seemed notto breathe. Thus sat he, wrapped up in contemplation, thinking Om, his soulsent after the Brahman as an arrow.Once, Samanas had travelled through Siddhartha’s town, ascetics on a pilgrimage, three skinny, withered men, neither old nor young, with dusty andbloody shoulders, almost naked, scorched by the sun, surrounded by loneliness, strangers and enemies to the world, strangers and lank jackals in therealm of humans. Behind them blew a hot scent of quiet passion, of destructive service, of merciless self-denial.In the evening, after the hour of contemplation, Siddhartha spoke to Govinda,“Early tomorrow morning, my friend, Siddhartha will go to the Samanas. Hewill become a Samana.”Govinda turned pale, when he heard these words and read the decision in themotionless face of his friend, unstoppable like the arrow shot from the bow.Soon and with the first glance, Govinda realized: Now it is beginning, nowSiddhartha is taking his own way, now his fate is beginning to sprout, andwith his, my own. And he turned pale like a dry banana-skin.“O Siddhartha,” he exclaimed, “will your father permit you to do that?”Siddhartha: An Open-Source Text5

Chapter 1. The Son of the BrahminSiddhartha looked over as if he were just waking up. Arrow-fast he read inGovinda’s soul, read the fear, read the submission.“O Govinda,” he spoke quietly, “let’s not waste words. Tomorrow, at daybreak I will begin the life of the Samanas. Speak no more of it.”Siddhartha entered the chamber, where his father was sitting on a mat of bast,and stepped behind his father and remained standing there, until his fatherfelt that someone was standing behind him. The Brahmin asked, “Is that you,Siddhartha? Then say what you came to say.”From the reading. . .“He had started to suspect that his venerable father and his other teachers, that the wise Brahmins had already revealed to him the most andbest of their wisdom, that they had already filled his expecting vessel with their richness, and the vessel was not full, the spirit was notcontent, the soul was not calm, the heart was not satisfied. ”Siddhartha replied, “With your

Comments. Michael Pullen originally produced the e-book for Project Gutenberg upon which this open source text is based. Translations were made by Gunther Olesch, Anke Dreher, Amy Coulter, Stefan Langer, Semyon Chaichenets, and proofreading was done by Chandra Yenco and Isaac Jones. Change