Transcription

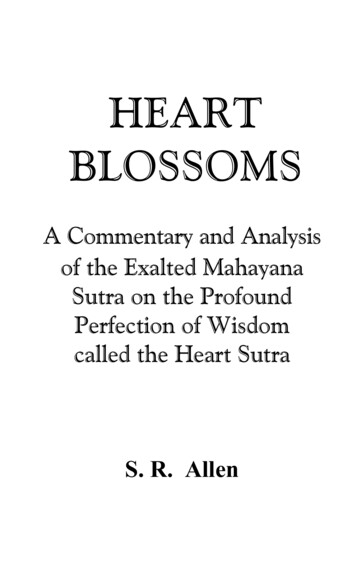

HEARTBLOSSOMSA Commentary and Analysisof the Exalted MahayanaSutra on the ProfoundPerfection of Wisdomcalled the Heart SutraS. R. Allen

Copyright 2013All Rights ReservedNo part of this book may be reproduced or usedin any manner whatsoever without the writtenpermission of the publisher, except in the case ofbrief quotations used in critical reviews orarticles.ISBN ’s978-0-9887067-3-6 (Hardcover)978-0-9887067-5-0 (Paperback)978-0-9887067-4-3 (e-book)U.S. Copyright OfficeRegistration Number: Txu 1-868-981Includes IndexSutrapitaka. Prajnaparamita.Prajnaparamitahridayasutra.English. 2013BQ.294.3

Dedicated in memory ofAni Sangmo

CONTENTSpagePreface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . viiIntroduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1The CommentariesChapter1. Study:The Arising of Srutamayiprajna . . . . . . . . . . . 172. The Title . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 233. The Prologue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 314. The Question and the Answer . . . . . . . . . . . . . .435. The Negations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .576. The Mantra . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 777. The Epilogue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 878. Thoughtful Reflection:The Arising of Cintamayiprajna . . . . . . . . . . . 919. Meditation:The Arising of Bhavanamayiprajna . . . . . . . .10710. Certainty:The Arising of Niscayamayiprajna. . . . . . . . 12511. Fullness:The Arising of Adhiprajna. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13912. Bodhi Svaha! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151Index. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

PREFACEIt seems necessary to record here a fewthoughts about what I have tried to accomplish bywriting this commentary on a famous Buddhist sutraabout which volumes have already been written, eachwith its own particular perspective or bias. Anykinds of comments may be made on any subjectcolored with personal bias according to whateveropinion or perspective a particular writer might have.In this work I have tried to eclipse all bias and pointout the few easily overlooked ideas contained in theHeart Sutra itself. Of course, any idea or statementfrom any source can be interpreted with biasconsonant with the degree of clarity or with thedegree of delusion of whomever is writing or ofwhomever is reading.In stark contrast to all the opinionatedinterpretations that pervade all aspects of our humancondition, whether in politics, in social collaborations,in philosophy, in religion, or in anything else, thisHeart Sutra is perfectly unyielding in its instructionspertaining to the necessity of getting beyond thevii

obscuring effects of any sort of discriminative biasand showing us the way to learn how to clearly seethe real truth. It is only the truth that can deliver usfrom our discontent.It may be that the one redeeming quality ofhumankind is its discontentedness. Beyond the basicwill-to-survive is an insatiable longing to know, andthroughout human history this longing is the basemotivation for all serious investigations concernedwith pursuing knowledge and finding real answers tothe perennial questions of philosophy, science, andreligion. In the end, with all the scriptures underlinedand all the sermons reiterated and grown old,uncertainty still remains and discontent persists justlike a magnified shadow that follows along with usevery day of our lives. The unknown something thatno finger can definitely point to, that no intellectualanalysis can seem to penetrate, and that no faith orsurrender can fully rely upon – whatever it is thatseems to be missing – that something persists inremaining missing. Even as I write this, the worldwe live in seems to be still searching for solutions tothe most simple problems, always in a process ofmaking some sort of “adjustment”. Eighty countriesand a thousand cities are undergoing demonstrations,riots, and breakdowns. It is as if someone has pusheda collective reset button. “Enough of this unnecessarysuffering,” people seem to be saying. Yet how muchpositive change can or will come if those who sufferviii

do not know of the real origin of suffering? Only byeliminating the originating factors that producesuffering can relief be found.The basic cause and condition for whatremains missing and for what subsequently goeswrong is our sense-based mind, that which maintainsignorance. However, no one need live a life saddledand constrained by ignorance and its consequentialactions. So it is crucial to know. An awakenedunderstanding of the true state of being allowsfreedom to anyone who is willing to see. Knowledgereleases one from the bonds of ignorance andobsessions based on a false notion of self and other.An integrated, dynamic consciousness is a necessityfor knowing the real situation of the human condition,whether individually or collectively. It is just thiskind of awareness about which the Heart Sutrainstructs. Without this kind of mature truth-vision weseem to wander perpetually in an automated chaos ofour own making.The explicit aim of Buddhism in its higherreaches, which the Heart Sutra represents, is therediscovery (or recovery) of what we really are, andof knowing with certainty what everything else reallyis. The task of the Sutra is to reveal this to us. Toremain in the common state of non-understanding isto miss the boat, or to end up carrying the boataround with us hoping to find a little more waterix

some place else on which we might float it again forfurther searching. The way of understanding is theway the Heart Sutra identifies as the clear way, apath well-marked when mind is allowed freedom fromdelusional bias, opinion, and expectation.With the intent to expose more of thepractical aspects of the way of bodhi as articulated inthis luminous sutra, this commentary is offered tothose who might find it of interest. I apologize for mymany shortcomings that may have limited the clearexpression of what is so difficult to clearly expresswith words, but trust that the approach hereinoutlined may serve in promoting a fuller vision of theway things really are.The Author, July 2011x

INTRODUCTIONThe Heart Sutra is the shortest sutra in theMahayana Buddhist collection of writings known asPrajnaparamita. There are about forty of thesesutras still extant in the Sanskrit language inapproximately six hundred volumes. ThePrajnaparamita Sutra are all intimately related toeach other because of the similarity of emphasisthey put on the realization of awakening throughthe blossoming of prajna (supreme, unequaledwisdom), and how this process is essential to theactivities of the bodhisattva idealism revealed andexplained in Mahayana Buddhism.The Prajnaparamita texts belong to thegenre of Buddhist writings called Vaipulya,scriptures originally written down in the Sanskritlanguage. But over time many of them have beenpreserved only in Tibetan or Chinese translations.These sutras were the first Mahayana scriptures tohave become widely available in India. The recordsof their emergence date to around 100 B.C.E.,1

about four hundred years after the Buddha’spassing. The Prajnaparamita Sutras are the mostextensive and voluminous of all the MahayanaSutras and are somewhat similar in structure to theearlier Pali Suttas in their method of teaching andin the treatment of subject matter.Some of the most reliable scholars ofBuddhism posit that unknown Buddhists groupscomposed the Mahayana Sutras directly fromrecords of the teachings of the Buddha. The oldlegends tell us that these texts were wisely hiddenaway by mysterious beings called nagas untilhumankind could achieve a higher ethics andmorality suitable to receive such knowledge in anappropriate fashion. The Mahayana writings werethen first introduced and confined to India by amonk named Nagarjuna. The Buddha hadpreviously said that such a one would be born inthe southern part of India about four hundred yearslater on, and that he would bear the name of thedragon. In Sanskrit the word for a “dragon inhuman form” is naga.Nagarjuna had given a discourse at theNalanda Monastery and was there told by nagasthat they had kept vital sutras safe in their underseacity, and that these would be available for him tostudy. And study them he did – for about fiftyyears – and then he took them and made them2

public in India. Later on Nagarjuna wrote manycommentaries on subjects of the Mahayana,t h e mo s t h i g h l y r ega r ded b eing h i sMulamadhyamakakarika, or “Root Verses of theMiddle Way”, an abstract exposition on the premierMahayana doctrine of emptiness. This became acore text of the later Madhyamaka School thatNagarjuna founded. Nagarjuna is said to have alsodiscovered other texts concealed in towers and otherplaces, and to have lived for more than six hundredyears.The Prajnaparamita Sutras consistentlymaintain a determined focus on the doctrine ofemptiness (sunyata), or the absence of any inherentor substantial self-existence of things. A Buddhistcontemplative practitioner, by way of aprogressively deeper understanding of emptiness, isthen enabled to manifest prajna-wisdom as abodhisattva on the Mahayana Path. ThePrajnaparamita Sutras extensively use an abstractverbal methodology that is effective in promotingdeep understanding in a student of these writings.This method induces the transcendence of theconditional and habitual verbal structures of adeluded individual mind-stream. This helps thecontemplative to deconstruct his errant formats ofperception and ideas that usually obstruct or hinderthe r ea lization of deeper insights. ThePrajnaparamita, or Perfection of Wisdom Sutras,3

extensively describe in many detailed ways, bothsimple and complex, the proper way in whichemptiness should be contemplated and understoodin order that awakening (bodhi) can occur.Most students of Buddhism will probablyhave come across a famous statement concerningemptiness that comes from the Heart Sutra itself:“. . .form is none other than emptiness andemptiness is none other than form. Form isemptiness and emptiness is form.” This somewhatmysterious statement will be clarified further on,and it is just this emptiness doctrine that impartsthe highest wisdom. It is widely agreed that onlythe Buddha taught emptiness, and it is found notjust in Mahayana writings, but also in Paliscriptures, though with less emphasis there. ThePrajnaparamita texts are essentially concerned withinstructions for bodhisattvas who, through deepinsight into emptiness, will correctly practice andperfect their skill in the six perfections (paramitas).This idea marks the beginning of the “secondturning of the wheel” of the Buddha’s teachings(dharmacakraparivartana) starting with thePrajnaparamita Sutras. The Pali scripturescontaining the “Three Baskets” of the writings(tripitaka) represent the “first turning of thewheel”. In Pali these are the Vinaya Pitaka, orrules of conduct for monks and nuns, the SuttaPitaka, which are the recorded discourses of the4

Buddha, and finally the Abhidamma Pitaka whichis the advanced and very detailed philosophicalpsychology of Buddhism. The second turningpresents a somewhat contrasting approach in theelucidation of the Two Truths compared with thatof the fist turning. These Two Truths are therelative truth (samvritisatya) and the ultimate truth(paramarthasatya), the meanings of which will beaddressed in a later section of this commentary.In the first turning there were those whowere having some difficulty overcoming theirconditioned tendencies to regard things asultimately real, so the Buddha began to expound thedeeper implications and meanings of emptiness tothem, and thus began the second turning which alsodepicts quite a contrast between the arhat of thePali Suttas and the bodhisattva of the MahayanaSutras. The main purpose of the second turning isto further reveal the truth about the realities ofexistence by means of the thorough exposition onemptiness, which in turn reveals the obviousnecessity of the paramitas by which the bodisattvasendeavor to move toward perfection and help othersalong the way. The third turning of the wheel isrepresented by the rest of the Mahayana Sutraswhich also reveal aspects of emptiness as well asexplaining such doctrines as the buddha-nature(tathagatagarbha), the mind doctrine (cittamatra),the three natures (trisvabhava), and other aspects5

of the Buddhadharma that complete and round outthe Buddha’s highest teachings.In the generations since the Buddha beganto elucidate the dharma there has been an unendingeffort to probe into the essence of these teachings.Since the Heart Sutra first appeared there havebeen numerous commentaries written on it by someof the most scholarly Buddhist teachers usingwidely divergent approaches. Among the mostwell-known commentaries are those written byAtisa, Jnanamitra, Kamalasila, Prasastrasena,Srisimha, Vajrapani, and Vimalamitra, all of India.From China, Fa-Tsang and Kukai stand out. FromTibetan tradition, Tendar Larampa, KenchogGromne, and the present Fourteenth Dalai Lamahave produced noteworthy explanations. Japan hadHakuin and several others. Today we find interestin the Heart Sutra has not waned at all and manyvolumes may be found which are written on it inrecent decades. Most of the commentaries, bothpast and recent, are written with the idea that theHeart Sutra presents a concise and mature formulawhich condenses the fundamental Prajnaparamitadoctrines in a valuable and useful way. The HeartSutra seems to be the centerpiece of the vast corpusof Prajnaparamita Sutras, hence its title, “Heart”(hridaya), meaning center, essence, or basis. Sincethis Heart Sutra is such a centerpiece of theMahayana emptiness doctrine, it seems auspicious6

to entitle this commentary according to the way thiswisdom blossoms in the contemplative practitionerfrom his/her own real essence.Several commentators have equated thesections of the Heart Sutra with the progressiveFive Paths of Buddhahood. These Five Paths arethe Path of Accumulation, Preparation, Vision,Meditation, and No More Learning. Although thereare undeniable similarities in the structure of theHeart Sutra with these Five Paths, nowhere withinthe Sutra itself are they specifically mentioned.There are also many other subjects covered in thePrajnaparamita Sutras that are not mentioned in theHeart Sutra, so when past commentators suggestthat the Heart Sutra is a condensation of all thePrajnaparamita Sutras, it must perhaps beunderstood as qualifiedly and relatively true.Nevertheless, the subject with which the HeartSutra is most concerned is the correct way toperceive emptiness and to incorporate that view andrealization into daily experience.A detailed curriculum of systematized anddetailed instruction was developed by Mahayanamonastic organizations based on the format andformulas of Nagarjuna. The students studied thetexts assiduously and heard discourses upon them.Then they reviewed and thoughtfully reflected onthem and learned how to debate over the wisdom7

contained in the sutras and commentaries. Next, inmeditation they learned to apply the knowledge theyhad gained. Further on it will be shown how theHeart Sutra indicates and encapsulates this samesystematic procedure of study, reflection, andmeditation.Upon rising from the samadhi “perceptionof the profound”, mentioned in the Heart Sutraprologue, the practitioner can, like the Buddha,clearly understand reality and existence andexperience in a practical and perfectly holistic wayinstead of in the usual narrow perspective ofautomated, preconditioned egotistic delusion. Thenthere can be a blossoming of prajna revealingbodhi, the awakening that gives freedom andcreative potential for the liberation of all beings.The Heart Sutra is found in both a longerand in a shorter version. This commentary refersmostly to the longer version, but both versions aresubstantially the same except for two differences.The first difference is that the shorter versionexcludes a prologue and an epilogue found in thelonger versions. The second difference is that theshorter version, in some translations, adds a line inthe first section, thus he overcame all ills andsuffering. The shorter version is found with andwithout this line. The only other differences8

between any versions must be attributed to previoustranslators of the Sutra who may have included orexcluded a word, or of other translators who haveused a clarifying creativity in their presentations.The shorter version has been chanted inmonasteries, temples, congregations, homes, andgatherings of Buddhists daily for fifteen hundredyears or more. It is held dear and esteemed withgreat loyalty and persistent devotion, memorizedand chanted worldwide in many diverse languagesstill today.The Heart Sutra is usually divided intosections by most commentators. The sections inthis commentary are called The Title, ThePrologue, The Question and the Answer, TheNegations, The Mantra, and The Epilogue. Thesesections are easily discerned in a casual reading ofthe Sutra. The following are English languagereadings of the longer and shorter versions.9

HEART SUTRA(Long Version)Arya Bhagavati PrajnaparamitahridayasutraThus did I hear at one time.The Conqueror was sitting on VultureMountain in Rajagriha with a great gathering ofmonks and a great gathering of bodhisattvas. Atthat time the Conqueror was absorbed in a samadhion the enumerations of phenomena called“perception of the profound”. Also at that timethe Bodhisattva, the Mahasattva Avalokitesvarawas contemplating the deep meaning of theProfound Perfection of Wisdom and he saw that thefive skandhas were all empty of inherent existence.Then, by the power of the Buddha, theVenerable Sariputra said this to the Bodhisattva,the Mahasattva Avalokitesvara, “How should thoseof good lineage train, who wish to practice theProfound Perfection of Wisdom?”The Bodhisattva, the MahasattvaAvalokitesvara said to the Venerable Sariputra,“Sariputra, sons and daughters of good lineage whowish to practice the Profound Perfection of Wisdom11

should view things in this way: they shouldcorrectly view the five skandhas also as empty ofinherent existence.”“O, Sariputra, form is none other thanemptiness and emptiness is none other than form.Form is emptiness and emptiness is form. Thesame is true for feelings, perceptions, mentalformations, and consciousness.Sariputra, allphenomena are characteristically empty, not creatednor destroyed, neither tainted nor pure, withoutincrease or decrease.”“Therefore, Sariputra, in emptiness thereare no forms, no feelings, no perceptions, no mentalformations, no consciousness; no eyes, no ears, nonose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no form, nosound, no odor, no taste, no touch, no object ofmind. There is no realm of eyes and so forth up toand including no mind consciousness. There is noignorance and no extinction of ignorance and soforth up to and including no ageing and no deathand also no extinction of ageing and death. Thereis no suffering, no origin, no cessation, and nopath. There is no wisdom and no attainment, withnothing to attain.”12

“Therefore, Sariputra, because bodhisattvashave nothing to attain, they rely on abiding in theProfound Perfection of Wisdom without mentalhindrances. Because their minds are withouthindrances they are without fear. Having passedcompletely beyond all errors they realize ultimatenirvana. All the buddhas of the three times havefully awakened into unsurpassed, completeenlightenment through relying on the ProfoundPerfection of Wisdom.”“Therefore, the mantra of the ProfoundPerfection of Wisdom is the great mantra, themantra of great knowledge, the unsurpassed mantra,the incomparable mantra, the mantra whichthoroughly allays all suffering without fail.Because it is not false it is known as true. Hence,the mantra of the Profound Perfection of Wisdomis stated asTadyatha om gate gate paragate parasamgatebodhi svaha!“Sariputra, bodhisattva mahasattvas shouldtrain in the Profound Perfection of Wisdom in justthis way.”13

Then the Conqueror rose from that samadhiand said to the Bodhisattva, the MahasattvaAvalokitesvara, “Well done, well done, well done,child of good lineage; it is just that way. TheProfound Perfection of Wisdom should be practicedjust as you have just taught it.Even theTathagatas admire this.” The Conqueror, havingthus spoken, the Venerable Sariputra, theBodhisattva, the Mahasattva Avalokitesvara, allthose gathered, and all those of the world, the gods,humans, demigods, and the gandharvas were filledwith admiration and they all praised theConqueror’s words.14

HEART SUTRA(Short Version)Arya Bhagavati PrajnaparamitahridayasutraThe Bodhisattva, the MahasattvaAvalokitesvara was contemplating the deep meaningof the Profound Perfection of Wisdom and he sawthat the five skandhas were all empty of inherentexistence; thus he overcame all ills and suffering.“O, Sariputra, form is none other thanemptiness and emptiness is none other than form.Form is emptiness and emptiness is form. Thesame is true for feelings, perceptions, mentalformations, and consciousness.Sariputra, allphenomena are characteristically empty, not creatednor destroyed, neither tainted nor pure, withoutincrease or decrease.”“Therefore, Sariputra, in emptiness thereare no forms, no feelings, no perceptions, no mentalformations, no consciousness; no eyes, no ears, nonose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no form, nosound, no odor, no taste, no touch, no object ofmind. There is no realm of eyes and so forth up toand including no mind consciousness. There is noignorance and no extinction of ignorance and soforth up to and including no ageing and no deathand also no extinction of ageing and death. There15

is no suffering, no origin, no cessation, and nopath. There is no wisdom and no attainment, withnothing to attain.”“Therefore, Sariputra, because bodhisattvashave nothing to attain, they rely on abiding in theProfound Perfection of Wisdom without mentalhindrances. Because their minds are withouthindrances they are without fear. Having passedcompletely beyond all errors they realize ultimatenirvana. All the buddhas of the three times havefully awakened into unsurpassed, completeenlightenment through relying on the ProfoundPerfection of Wisdom.”“Therefore, the mantra of the ProfoundPerfection of Wisdom is the great mantra, themantra of great knowledge, the unsurpassed mantra,the incomparable mantra, the mantra whichthoroughly allays all suffering without fail.Because it is not false it is known as true. Hence,the mantra of the Profound Perfection of Wisdomis stated asTadyatha om gate gate paragate parasamgatebodhi svaha!“Sariputra, bodhisattva mahasattvas shouldtrain in the Profound Perfection of Wisdom in justthis way.”16

CHAPTER 1STUDYThe Arising of SrutamayiprajnaNAMO BUDDHADHARMASANGHAYA ANDHOMAGE TO ALL THE WARRIOR SAINTSAND ENLIGHTENED BEINGS OF THETHREE TIMES. PEACE TO ALL BEINGS.In the vast and deep dharma oceanOf the Buddha’s glorious teachingsThere is a tiny droplet, Heart Sutra,Which exposes the wisdom of the profound.Examining this droplet diligentlyIt is found equal to the whole ocean.By contemplating its deep meaningWe study attentively for great knowledge.By training thoughtfully in the correct viewWe reflect on our conceptual errors.In practicing the Profound Perfection of WisdomWe meditate for calm and insight.Understanding then with certaintyWe transcend all mental hindranceAnd through heightened full awarenessWe experience the blossoming of prajnaAnd abide in the dharma ocean of truth,Free and filled with admirationFor the Sutra’s profound words.17

This short poem introduces this monographand refers to a five-phase progression in the wayprajna blossoms into bodhi. This is given in the textof the Heart Sutra itself and is inherent in itsformat:The first clue revealing the sutra’shidden structure is, . . . Avalokitesvara wascontemplating the deep meaning of theProfound Perfection of Wisdom. . . . Herethe word contemplating refers to study(sruti). This study is covered in ChapterOne of this commentary.The second in the progression is“How should those of good lineage train,who wish to practice the ProfoundPerfection of Wisdom?” In this case theword train refers to thoughtful reflection orcritical analysis (cinta), a deeper level ofstudy that deeply impresses upon thememory and understanding. Training, orthoughtful reflection is covered in ChapterEight of this commentary.The third step mentioned is “ . . .whowish to practice. . . .” The word practicerefers to the practice of meditation(bhavana). These first three steps, sruti,cinta and bhavana are descriptive of thethree root prajnas (mulaprajnas) of18

Mahayana Buddhism, srutamayiprajna,cintamayiprajna, and bhavanamayiprajna.These are related to the methodology of thePrajnaparamita Sutras. Bhavana is thesubject of Chapter Nine.The fourth clue is “Having passedcompletely beyond all errors they realizeultimate nirvana.”Someone who hasreached this stage is certain of having passedcompletely beyond all errors since he/she iscertain of an errorless mind. Clarity ofunderstanding is certainty (niscaya), whichis the subject of Chapter Ten.The fifth and last in the series is,“. . .they realize ultimate nirvana,” and“. . .have fully awakened . . . .” Thisrefers of course to bodhi and the highestlevel of prajna (adhiprajna), which isdescribed in Chapter Eleven.The fourth and fifth prajnas arise from thethree root prajnas when developed in order.According to these clues and others within the HeartSutra we are furnished with a definite and distinctway of development culminating in awakening.These five prajnas are not separate qualities ofwisdom, but are meant to indicate the stages of theblossoming of prajna into full awakening. As wewill discover further on in this investigation, these19

five prajnas also accord perfectly with the obviousprogression of the Heart Sutra mantra:gate srutamayiprajnagate cintamayiprajnaparagate bhavanamayiprajnaparasamgate niscayamayiprajnabodhi adhiprajnaAccording to the Sutra, the same progressionis exactly how awakening comes about.Studying (sruti) the elements and parts of thetext of the Heart Sutra means becoming familiarwith terminology and the ideas presented therein.This is the preliminary prerequisite to further anddeeper study and expanded analysis of these ideasthat entails a thoughtful reflection (cinta). Once thesrutamayiprajna arises, it supports the arising ofcintamayiprajna. Study is a fairly undeveloped stagebut further and deeper reflection does developthrough studious enquiry. The Heart Sutra treatsstudy and thoughtful reflection similarly as gate,gate – the second gate indicating a more thoroughprogression of the same idea.Study is the necessary preliminary to thearising of insight (vipasyana). This is the formatfor practice of meditation (bhavana) according to theHeart Sutra. Training (cinta) is the necessarypreliminary for gaining confidence and understanding20

in preparation for meditation by which certainty ofthe deep truth of emptiness comes about. Trainingis a deeper level of study, thoughtful reflection.Practice is the practice of meditation through whichthe first two root prajnas come to fruition. Whenmeditation is successful, the three root prajnas haveblossomed and give rise to further perfection ofwisdom. Certainty (niscayamayiprajna) then arisesand stability in concentration and realization ariseswith it through persistently advancing through thefirst three root prajnas. A contemplative practitionermust develop certainty of the truth of emptiness.Simply by understanding the method of the HeartSutra we can easily become confident of a direct andcertain awakening. Fullness (adhiprajna) is theheightened or complete aspect of prajna-wisdom and,in its fullness of holistic apperceptive wisdom,equates with bodhi. This is the culmination of theblossoming of prajna into bodhi and thus, “. . .fullyawakening into unsurpassed complete enlightenmentthrough relying on the Profound Perfection ofWisdom.”This is the explanation of the introductorypoem regarding the structure and method of theHeart Sutra that begins our study.21

CHAPTER 2THE TITLE:ARYA BHAGAVATIPRAJNAPARAMITAHRIDAYASUTRAThis is the full title of the Heart Sutra.Looking at its component parts, Arya means“saintly” or “holy”, a noble one who has attained,is accomplished or is liberated.Bhagavati is the key to the structure andmethod of the Heart Sutra text, and especially theabstract meaning of its mantra.Prajnaparamitahridayasutra means “Sutra onthe Heart of the Transcendent Perfection ofWisdom.”To explore these aspects it is appropriate tobegin with the following quote from the sutra:“All the Buddhas of the three times havefully awakened into unsurpassed completeenlightenment through relying on theProfound Perfection of Wisdom.”23

This line in the Sutra tells us that allbuddhas are born into bodhi from the matrix wombof the Mother (Bhagavati) who herself is prajna.The One Hundred Thousand Line Sutra on PerfectWisdom explains, in the Buddha’s words, that, justlike a woman with many children is well looked afterby them and protected by them because they knowshe is their mother and has taught them how to livein the world, in the same way the Tathagatas arealways mindful of the Perfection of Wisdom. TheTathagatas know very well that prajna is the motherof buddhas, and instructs them in realization ofBuddhadharma, which is completed in fullenlightenment.This is the implication of the full title anduse therein of the term Bhagavati, the femininegrammatical form of Bhagavat, the name usuallyused to refer to the Buddha Sakyamuni. Bhagavatmeans blessed or one who has acquired omniscientwisdom through enlightenment, one who has finishedwith becoming and perfectly developed himself bydoing away with all fears and troubles and byabolishing all defilem

HEART BLOSSOMS A Commentary and Analysis of the Exalted Mahayana Sutra on the Profound Perfection of W