Transcription

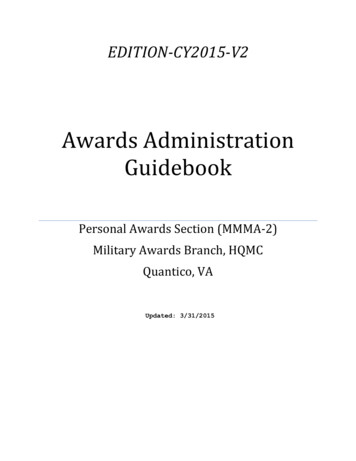

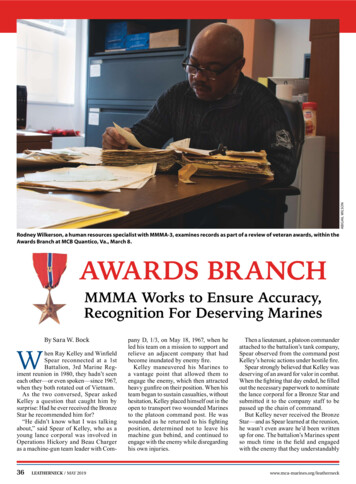

ABIGAIL WILSONRodney Wilkerson, a human resources specialist with MMMA-3, examines records as part of a review of veteran awards, within theAwards Branch at MCB Quantico, Va., March 8.AWARDS BRANCHMMMA Works to Ensure Accuracy,Recognition For Deserving MarinesWBy Sara W. Bockhen Ray Kelley and WinfieldSpear reconnected at a 1stBattalion, 3rd Marine Reg iment reunion in 1980, they hadn’t seeneach other—or even spoken—since 1967,when they both rotated out of Vietnam.As the two conversed, Spear askedKelley a question that caught him bysurprise: Had he ever received the BronzeStar he recommended him for?“He didn’t know what I was talkingabout,” said Spear of Kelley, who as ayoung lance corporal was involved inOperations Hickory and Beau Chargeras a machine gun team leader with Com 36LEATHERNECK / MAY 2019pany D, 1/3, on May 18, 1967, when heled his team on a mission to support andrelieve an adjacent company that hadbecome inundated by enemy fire.Kelley maneuvered his Marines toa vantage point that allowed them toengage the enemy, which then attractedheavy gunfire on their position. When histeam began to sustain casualties, withouthesitation, Kelley placed himself out in theopen to transport two wounded Marinesto the platoon command post. He waswounded as he returned to his fightingposition, determined not to leave hismachine gun behind, and continued toengage with the enemy while disregardinghis own injuries.Then a lieutenant, a platoon commanderattached to the battalion’s tank company,Spear observed from the command postKelley’s heroic actions under hostile fire.Spear strongly believed that Kelley wasdeserving of an award for valor in combat.When the fighting that day ended, he filledout the necessary paperwork to nominatethe lance corporal for a Bronze Star andsubmitted it to the company staff to bepassed up the chain of command.But Kelley never received the BronzeStar—and as Spear learned at the reunion,he wasn’t even aware he’d been writtenup for one. The battalion’s Marines spentso much time in the field and engagedwith the enemy that they understandablywww.mca-marines.org/leatherneck

www.mca-marines.org/leatherneckCOURTESY OF NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE MARINE CORPSAfter presenting Ray Kelley, center, with the Silver Star for his actions in Vietnam onMay 18, 1967, Capt Winfield Spear, USMC (Ret), second from left, addresses those inattendance at a ceremony at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, May 18, 2018.COURTESY OF NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE MARINE CORPSfell behind in keeping up with paperworkand administrative tasks. The paperworkfor the award, they surmised, must havebeen lost or misplaced. Like many whoserved in Vietnam, their focus was not onawards, but simply on making it home,then trying to find some sense of normalcywhile dealing with visible and invisiblewounds as well as with hostility fromthose who opposed the war.“We all went in the closet, so to speak,”said Kelley of life upon his return homefrom Vietnam.After the 1980 reunion, Kelley andSpear again went their separate ways,both certain that too much time hadpassed to do anything about the awardthat was well-deserved but had never beenreceived.“I didn’t follow up on this, because inmy opinion it was too late to do anything,”recalled Spear.Many more years went by, but in theearly 2000s, Spear started to think aboutthe missing paperwork and couldn’t shakea growing sense of duty to see it through.The more he thought about it, the moredetermined he became.“I said, ‘I’m going to get it done,’ ”he recalled—and instead of the BronzeStar, this time he was going to nominateKelley for the Silver Star. After readingnumerous award citations, which at thispoint were being written for the actionsof U.S. servicemembers in Afghanistan,Spear was certain that Kelley’s heroismin May 1967 warranted the nation’s thirdhighest award for valor in combat.He had no idea where to begin, so hevisited the local Marine reserve unit inAlbuquerque, N.M., near his home, wherehe spoke with a first sergeant on the I&Istaff. The first sergeant gave him a copyof the OPNAV 1650 form he would need tosubmit, and Spear completed it to the bestof his ability with the help of his wife, whohe says was instrumental in helping himnavigate the process. He then submittedthe form to Headquarters Marine Corps.What Spear didn’t realize at the timewas that this would be the beginning ofan approximately 15-year effort, full offrustrations and roadblocks.Because nearly 40 years had passedsince Kelley’s actions, each requiredtask was far more difficult and timeconsuming than Spear anticipated.The award recommendation requiredendorsements from officers in Kelley’schain of command. Spear solicited thehelp of Ken Hicks, who was a lancecorporal in Kelley’s unit and was now aretired major, to help him in his effortsto track them down.As a lance corporal serving as a machine-gun team leader with Co D, 1/3 duringOperations Hickory and Beau Charger in 1968 in Vietnam, Ray Kelley, left, repeatedlyexposed himself to enemy gunfire in order to transport wounded Marines to safety.He continued to engage the enemy even after he was injured.Hicks and Spear spent two or three yearstrying to locate the company commander,Captain Edmund Aldus, before learningthat he had passed away in 1995.Around the same time, they trackeddown two eyewitnesses who, like Spear,had observed Kelley’s heroism that day:a Marine from Kelley’s gun team and arifleman from Spear’s platoon who volun-teered to go forward when the shootingintensified. Both provided affidavits thatcorroborated the proposed citation andsummary of action Spear had written asthe originator of the award.As he made progress, Spear continuedto submit paperwork to Headquarters Marine Corps, but without all of the requireddocuments they were unable to verifyMAY 2019 / LEATHERNECK37

Records were archived using microfilm, which is stored in labeled boxes and drawers,(above) until the early 2000s. Today, a digital awards processing system is used.Awards specialist Betty Hill, (right and above right), loads a microfilm reel to viewhistorical records belonging to the Awards Branch, March 8 at MCB Quantico, Va.(Photos by Abigail Wilson)the award in order to pass it on to theapplicable review board. He had rewrittenthe proposed citation numerous times,but it still wasn’t quite what they werelooking for.Since the company commander wasdeceased, Spear focused his efforts ongoing up the chain of command and begansearching for Major Peter Wickwire, whowas the battalion commander at the timeof the incident. This search ended on apositive note: Wickwire, now a retiredcolonel, was still living and would do whathe could to help.But just when his persistence seemed tobe paying off, a series of hospitalizationsand health issues forced Spear to put theproject on the back burner for two years.“I dropped this whole thing,” Spearsaid. Until one day, when an unexpectedphone call changed everything. On theother end of the line was Betty Hill, anawards specialist with Headquarters Ma rine Corps’ Awards Branch, ManpowerManagement Military Awards (MMMA),located at Marine Corps Base Quantico,Va.Hill had reviewed a file that containedall of the paperwork Spear had submitted38LEATHERNECK / MAY 2019over the years. She told Spear that shebelieved that Kelley had a strong case for aSilver Star, and explained what he neededto do to submit a package that could beverified by the Awards Branch and passedup the Marine Corps chain of commandbefore being reviewed by the Secretary ofthe Navy’s awards board and the Secretaryof the Navy himself, the approval authorityfor historical awards. He needed to againrewrite the proposed citation and providea minute by minute account of Kelley’sactions, and the battalion commander—Col Wickwire—would have to endorsethe OPNAV 1650. By this point, botheyewitnesses had passed away, but thesworn statements Spear had collectedfrom them years earlier remained valid.It would take a year after the completepackage was submitted, but another phonecall from Hill late in 2017 brought Spearthe news he had been waiting for. Kelley’sSilver Star finally had been approved, 50years after his actions.Spear was overjoyed to call Kelley andshare the news after he had begun plan ning a presentation ceremony on a par ticularly important day. On May 18, 2018,the 51 year anniversary of the incident,Kelley was awarded the Silver Star at theNational Museum of the Marine Corpsin Triangle, Va.In the audience that day was Betty Hill,and when it was his turn to speak, Spear,who had the honor of presenting the SilverStar to Kelley, made sure to acknowledgeher for her integral role in getting theaward processed.“I introduced her and said that if ithadn’t been for her, I don’t think we’d behere today. This was the lady that pulledwww.mca-marines.org/leatherneck

it all together,” said Spear of his remarksto the 160 individuals who attended.Hill, who has 26 years of awards exper ience, is one of a staff of 12 civilians andfive active-duty Marines who make upthe Awards Branch, which is tasked withdeveloping awards policy and processingall awards, both active duty and historical,as well as responding to inquiries fromCongress, the Secretary of Defense, theSecretary of the Navy (SECNAV), theCommandant of the Marine Corps andindividuals regarding specific awards.Kelley’s Silver Star is just one of anumber of Vietnam era awards thathave made headlines around the Corpsin recent years. Most notably, in October2018, Sergeant Major John L. Canleywas awarded the Medal of Honor for hisactions at Hue City in 1968, an upgradefrom his previously awarded Navy Cross.These “historic awards” were madepossible through the National DefenseAuthorization Act of 1996, Title 10, Sec tion 1130, which allows for awards to beapproved outside the time limit of threeyears to originate an award and five yearsto present it.In order to be approved, upgrades likeCanley’s Medal of Honor require new andrelevant information that wasn’t availableat the time of the action, said Hill, addingthat the majority of the “1130 cases” arefor new awards, like Kelley’s Silver Star,and not for upgrades.Many of the 1130 cases are originatedafter reunions and annual get togetherswhen veterans discuss awards, said MajorAlejandro Quinn, USMC (Ret), who worksalongside Hill in MMMA-3, whichhandles historical awards. What manyMarines don’t realize, said Quinn, is howmuch extensive research is conductedafter a package is submitted to them.“The process is not an easy process,”said Quinn. “We can get a case and it’lltake us a month or longer just to researchand get ready. Some cases, because wehave to send them back for corrections,take six months to a year to locate peopleand get people to sign things and getdocuments rewritten. And that’s beforeyou even go before the board.”Each award request must go through amember of Congress in order to be con sidered, but just because a representative’soffice submits it to the Awards Branchdoesn’t mean the package is complete.Quinn and Hill often communicate atgreat lengths with the actual originatorof the award—like Hill did with CaptSpear—to get everything submitted prop erly. It’s important to note that the lawrequires that the service branch act as thewww.mca-marines.org/leatherneckA stack of records and paperwork sits on a desk in the MMMA-3 office at MCB Quantico,where a dedicated staff handles the review process for historical awards. The processof extensively researching and validating the 1130 cases is extremely time consumingand must be completed before an award nomination can be passed to a review board.(Photo by Abigail Wilson)neutral processing party and may notcompile any of the original package, saidColonel Emily Swain, USMC (Ret), theMMMA branch head. And when reviewing requests for historical awards, theAwards Branch staff must follow theguiding regulations for awards that werein place at the time of the event in ques tion—not the rules that are in place today.When they receive a Section 1130case for an award from World War II, forexample, they have to look at the SECNAVregulation for that award during WorldWar II.“One of the things to emphasize hereis the level of research and detail to makesure that the award is written in a way thatis accurate for the award they’re beingsubmitted for,” said Gunnery SergeantEdward Mosley, USMC (Ret), MMMA-3section head.The majority of the Section 1130 re MAY 2019 / LEATHERNECK39

“Unfortunately this is a long process,but our goal is to make sure that the bestpossible package is sent forward,” saidHill. “We never guarantee that an awardis going to be approved, but we guaranteethat we put forth every effort to verify, andthe board will receive the best packagepossible.”Not only does MMMA-3 process Section 1130 requests, but its staff also hasSGT ANDY MARTINEZ, USMCCPL ALEXANDER HILL, USMCThe wars in Iraq and Afghanistan broughtto the forefront the need to revise criteriafor certain awards. In 2011, one such re vision was made when mild TBI wasadded to the list of injuries that mayqualify for the Purple Heart due to thegrowing research surrounding the long term effects of IED blast exposure.been tasked with handling a series ofreviews ordered by Congress to determinewhether certain Marines were discriminated against and wrongfully denied theMedal of Honor. They currently are inthe process of reviewing the records ofAsian American and Native AmericanPacific Islander war veterans, and havecompleted reviews of Jewish American,African-American and Hispanic American Marines who received the Navy Crossbut may have been deserving of thenation’s highest award for valor.Throughout history—and particularlyover the past two decades—changes to thenature of warfighting have necessitatedchanges to the Marine Corps’ awardssystem.“In regular peacetime, awards are not aspresent an issue,” said Swain. “Awards aremore in the forefront—there’s an entirenew generation of Marines that are nowvery engaged in doing amazing things andbeing in a position to be observed doing allthese amazing things,” she added, notingthat the words “while engaged with theenemy,” specific to awards for action orservice in combat, is a phrase that Marinesin some eras never would have dealt with.For post-9/11 veterans in particular,emerging technology and changingwarfare have transformed the battlefieldand required the Department of Defenseto reevaluate criteria for certain awards.In 2011, the Corps implemented revisedcriteria for the Purple Heart that liftedUSMCquests the Corps has received in recentyears are from the Vietnam War, but therehave also been some from actions duringWorld War I and World War II, as wellas a few from Operation Iraqi Freedom.Another time-consuming step in theresearch and verification process involvesordering records from the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Mo.,the repository for military personnelrecords. The records are not digitized,so once they are ordered it can take upto six months or more to receive them.Sometimes, the records requested areon loan to another agency or entity, suchas the Department of Veterans Affairs,and can’t be transferred to MMMA untilthey’ve been returned. The Awards Branchis required to not only verify the recordsof the Marine who is recommended for anaward, but also the records of the awardoriginator, each of the eyewitnesses andmembers of the command. This helpsdetermine the legitimacy of their claims.“Everything is validated to verifyeach person’s whereabouts in comparisonto the incident,” said Quinn.If they are able to verify everythingin the awards package using individualrecords, unit records, command chronologies and historical resources, thestaff then puts together a research paperoutlining everything they have discoveredand reviewed, said Hill. Everything is thensent to the branch head for approval; if itpasses muster, it is submitted to the board.During a Feb. 1 ceremony in Portland, Ore., Maj Edward F. Wright, USMC (Ret), pictured on the left in Vietnam as a second lieutenantserving with “Lima” Company, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, was awarded the Silver Star for his actions on Aug. 21, 1967,when he led a reaction force to rescue soldiers and Marines who had been pinned down by the enemy, exposing himself to intenseenemy fire and successfully rescuing the surrounded troops.40LEATHERNECK / MAY 2019www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck

During a March 8 meeting, MMMA staff members, from the left, Rodney Wilkerson, Jon Vigon, Betty Hill, Maj Kimberly Wade,Alejandro Quinn and Capt Nelson Hooker discuss their current workload and taskings at MCB Quantico, Va. The Awards Branchstaff is made up of 12 civilians and five active-duty Marines who develop awards policy and process all awards, both active dutyand historical. (Photo by Abigail Wilson)www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck“R” (remote impact) and “C” (combatconditions). Service specific achievementmedals are no longer eligible for the “V”device, which is now only authorized onawards recognizing specific acts of valor.The new “R” device is now authorizedon certain personal decorations “to denotethe medal was awarded for the directhands on employment of a weapon system,or for other warfighting activities that hada direct and immediate impact on a combatoperation or other military operation froma remote location.” Intended for droneoperators, cyber network operatorsSilver StarPurple HeartABIGAIL WILSONthe requirement for a Marine to have lostconsciousness due to a mild traumaticbrain injury (TBI) in order to qualify forthe Purple Heart. Instead, Marines whosustain concussive injuries caused byenemy action and remain conscious mayqualify for the medal if they are deter mined by a medical officer as “not fit forfull duty due to persistent signs, symptomsor findings of functional impairment fora period greater than 48 hours from thetime of the concussive incident.” Thechange, which was made retroactive toSept. 11, 2001, was influenced by a grow ing body of research within the Depart ment of Defense regarding mild TBI—often caused by blast exposure fromimprovised explosive devices (IEDs)—and its long term effects.The prevalence of IEDs in Iraq andAfghanistan also led to a 2012 changein the eligibility criteria for the CombatAction Ribbon, determining that Marinesand Sailors could receive the award fortaking “direct action to disable, rendersafe, or destroy an active enemy emplacedimprovised explosive device (IED), mine,or scatterable munition” after Oct. 7, 2001.Most recently, in 2017, in responseto new Department of Defense widepolicies concerning devices worn oncertain awards, the Corps issued guidanceregarding the bronze letter “V” (valor)device as well as two brand new devices—As of 2017, devices authorized for wear on certain awards now include the “C” forcombat conditions and “R” for remote impact. The bronze letter “V” for valor is nowonly authorized on awards recognizing specific acts of valor, a departure from pastDOD policy.MAY 2019 / LEATHERNECK41

regulations from the time in question stillapply to those award requests.“We no longer do the Navy and MarineCorps Achievement Medal with ‘V’ forthe current force; however, [on] a historiccase from Vietnam our board can still goback and recommend a NAM with ‘V’because those rules existed at the time,”said Hooker. “On the flip side of that,someone from Vietnam or World War IIor Korea could not receive a Navy andCPL PATRICK OSINO, USMCand in some cases joint terminal attackcontrollers, forward air controllers orartillery Marines, among others, theaddition of the device acknowledges therole that technological advancementsincreasingly play in Marines’ ability toimpact the battlefield from outside the“enemy threat envelope.”For meritorious service under combatconditions, the “C” device is authorizedfor a number of awards—among them, theNavy and Marine Corps CommendationMedal and the Navy and Marine CorpsAchievement Medal—in which the re cipient was personally exposed to hostileaction or was at significant risk of suchan exposure. It is not authorized on theBronze Star or other valor awards, as thosealready require exposure to hostile action.The new devices and the accompanyingrules and regulations only apply to awardsfor which the date of action was on orbefore Jan. 7, 2016.According to Captain Nelson Hooker,MMMA 2, who handles all the personalawards for the current force, it’s importantto note that in historic cases, the awardABIGAIL WILSONCapt Nelson Hooker, MMMA-2, is responsible for handling all of the personalawards for current active-duty Marines.His advice to today’s Marines is to learnfrom the past and submit awards immediately after the action occurs.BGen Stephen M. Neary, CG, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, left, and SgtMaj JoyM. Kitashima, right, present a Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal to LCplMatthew Ellis, a 2nd MEB intelligence specialist, at MCB Camp Lejeune, N.C., Dec. 11,2018. The Awards Branch staff emphasizes the importance of recognizing Marines formeritorious service or acts of valor and strives to ensure that all are given the creditthey deserve.42LEATHERNECK / MAY 2019Marine Corps Commendation [Medal]with the ‘R’ device because the ‘R’ devicewasn’t in existence at the time.”Changes in technology have not onlyaffected the criteria for certain awards,but also have improved the way theAwards Branch processes them. Sincethe early 2000s, the Corps has used anawards processing system in which theentire process is digitized. The newestiteration of the system, the improvedawards processing system (iAPS), wasmerged with the existing system almosta decade ago, and is considered to bethe premier system for processing andarchiving awards within the Departmentof Defense.Looking to the future, Major Quinnbelieves that iAPS will help streamlinethe process for historical awards.“Assuming the 1130 processing isgoing to continue on 50 years from now,whoever succeeds us will be able to havebetter records,” said Quinn. “We havethose right at our fingertips and it cutsdown on a lot of our research time.”Speaking to the current active dutyforce, Hooker emphasized the importanceof submitting awards in a timely mannerwithin the three year time limit so thatthe award won’t be considered a section1130 request. His advice: get the awardin immediately after the action.“As time goes by, it’s a lot harder torecall those things the time keepsdragging by, suddenly chain of commandmembers are deceased, originators aredeceased, and that makes it 10 timesharder,” said Hooker.A retired gunnery sergeant, Mosleyurges Marines to not undervalue theiraccomplishments, and encourages leadersin the Corps not to undervalue the actionsof their Marines.“We as Marines say, ‘We’re just doingour job,’ ” said Mosley. “We’re taught tobe hard, tough, but humble, and a lot oftimes with these Vietnam 1130 cases itwas the same then. They were humble—‘just doing my job’—and then years laterthey’re getting together and they talkabout these things but at that pointit’s tough and it’s a long process.”Whether an award is presented a fewmonths after an action or 51 years later,as in Raymond Kelley’s case, it is vitallyimportant that deserving Marines aregiven the recognition they are due.Yvonne Carlock, the deputy communi cations and strategy officer for Manpower& Reserve Affairs, echoed Mosley’ssentiments:“What a lot of people consider valor,Marines consider duty.”www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck

the Awards Branch, which is tasked with developing awards policy and processing all awards, both active duty and historical, as well as responding to inquiries from Congress, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV), the Commandant of the Marine Corps a