Transcription

Lest We Forget: The Lynching of Will Brown, Omaha’s 1919 Race Riot(Article begins on second page below.)This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You maydownload it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information,see: shs-materialsLearn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) raska-history-magazineHistory Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History /membershipFull Citation: Orville D Menard, “Lest We Forget: The Lynching of Will Brown, Omaha’s 1919 Race Riot,”Nebraska History 91 (2010): 152-165.URL: e: 3/1/2019Article Summary: A mob stormed the burning Douglas County Courthouse on September 28, 1919, and lynched anAfrican American, Will Brown. The victim, accused of raping a white woman, had no opportunity to prove hisinnocence. Political boss Tom Dennison and his allies may have encouraged the lynching in order to discreditMayor Edward P Smith, an advocate for reform.Cataloging Information:Names: William Brown, Chris Hebert, Henry Fonda, Milton Hoffman, Agnes Loeback, Marshall Eberstein, Tom“the Old Man” Dennison, John A Williams, Edward Rosewater, James Dahlman, Edward P Smith, WilliamFrancis, Harry B Zimman, Asel Steere, Leonard Wood, Ralph Snyder, Claude NethawayPlace Names: Omaha, NebraskaKeywords: lynching, racism, segregation, covenants, William Brown, Douglas County Courthouse, MiltonHoffman, Agnes Loeback, Marshall Eberstein, “Red Summer,” Omaha World-Herald, Omaha Bee, Second GreatExodus, Central Labor Union, Industrial Workers of the World, “New Negro,” African Americans, Monitor,Omaha Daily News, William Francis, Tom “the Old Man” Dennison, John A Williams, Edward Rosewater, JamesDahlman, Edward P Smith, Leonard Wood, Ku Klux KlanPhotographs / Images: burning of the Douglas County Courthouse, September 28, 1919; Omaha’s Riot in Story andPicture photographs: Will Brown, arrival of police patrol, mob on south side of courthouse (2 views), burning ofthe police patrol, pole on which Brown was hanged, historic cannon used by mob as a battering ram, soldiers onguard at Twenty-Fourth and Lake Streets; rioters on the south side of the courthouse; bullet holes in the treasurer’soffice window; spectators gathered around Brown’s body (2 views); inset upper half of Omaha World-Herald frontpage, September 29, 1919; wreckage in Judge Sears’s office; Red Cross women in their courthouse headquartersafter the riot

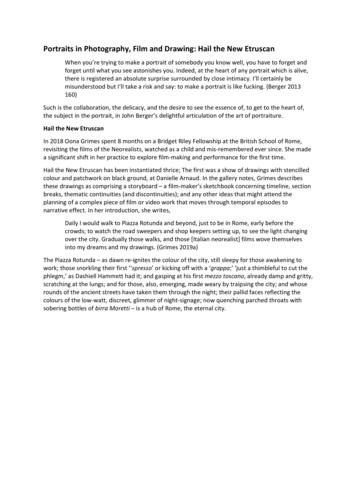

Lest We Forget:The Lynching of Will Brown,Omaha’s 1919 Race RiotB y O r v i l l e D. M e n a r dThe burning of the Douglas CountyCourthouse, Omaha, September 28, 1919.The mob in the street is barely visible bythe light of the flames. NSHS RG2281-71

FFrom Omaha’s Riot in Story and Picture(Omaha: Educational PublishingCompany, 1919).or almost a hundred years, Will Brown’sbullet-ridden and charred remains lay inan unmarked grave in the potter’s field ofOmaha’s Forest Lawn Memorial Park. Accusedof raping a white woman, Brown was takenfrom the burning Douglas County Courthouseby a riot-crazed mob. Beaten as he avowed hisinnocence, his bleeding body was dragged toswing at the end of a rope, and repeatedly shot.According to his death certificate, Brown diedon September 28, 1919, age about forty, a laborerby trade, marital status unknown, birthplaceunknown, as were the names of his parents. Thecause of death was “bullet wounds through thebody and lynched.”1Today Brown has a gravestone, donatedby Californian Chris Hebert, who learned in aHenry Fonda television special of Omaha’s riotand Brown’s murder. The donor had no connection with Omaha and asked only that “Lest weforget” be engraved on the stone. “It’s too badit took deaths like these to pave the way for thefreedoms we have today. . . . I got the headstonethinking that if I could reach just one person, itwas well worth the money spent.”2The circumstances of the riot and Brown’sdeath remain controversial. Was he guilty ofrape or was he innocent, physically incapableof the feat? Was the riot a spontaneous eruptionof fervor, reflecting a violent “spirit of the times”in a year of social and economic anxieties? Orwas it a politically inspired event, designed todiscredit the city’s administration?

Around midnight on September25, 1919, Milton Hoffman and Agnes Loeback wereassaulted at Bancroft Street and Scenic Avenue asthey were walking home after a late movie. Theysaid their assailant robbed them at gunpoint,taking Hoffman’s watch, money, and billfold, plusa ruby ring from Agnes. He ordered Hoffman toFrom Omaha’s Riot in Storyand Picture.From Omaha’s Riot in Story and Picture.154 nebraska historymove several steps away, then dragged nineteenyear-old Loeback by her hair into a nearby ravineand raped her.3On Friday the twenty-sixth, an Omaha Bee headline proclaimed that a “black beast” had assaulteda white girl. Police and detectives combed the vicinity for two hours, joined by four hundred armedmen under the leadership of Joseph Loeback(Agnes’s brother) and Frank B. Raum. The groupincluded railroad workers who knew Agnes fromher job at an eatery (she also worked in a laundry).A neighbor told the searchers of a “suspicious negro” living in a house at 2418 South Fifth Street witha white woman, Virginia Jones, and a second blackman, Henry Johnson. Raum and four of his menfound William Brown at the house and coveredhim with a shotgun. Arriving on the scene, policefound Brown hiding under his bed. They took himto Loeback’s home nearby, bringing with themclothes found in Brown’s room.4

From Omaha’s Riot in Storyand Picture.Loeback and Hoffman identified Brown as theirassailant. Her description of him tallied with thatof a mugger in the vicinity three weeks earlier. Agnes also identified the clothing, including a whitefelt hat that had been worn by a man seen in theGibson neighborhood. Later, however, Agnes statedthat her attacker was black, but “I can’t say whetherhe [Brown] is the man or not.” Hoffman, arrivingat the Loeback home, identified Brown “with notthe least bit of doubt but what he is the Negro who”held him at gunpoint while he raped Agnes.5By then a crowd of some 250 men and womenhad gathered around the house, shouting thatBrown should be lynched. They struggled withthe police and twice succeeded in putting a ropearound Brown’s neck. Despite slashing of tiresand beatings, the police prevented a lynching andtook Brown first to the police department’s jail, andthen to the new Douglas County Courthouse jail,where they believed he would be safer. Chief ofPolice Marshall Eberstein said he did not know ifBrown was guilty and that further investigationwas necessary.Across the nation, stories ofracial violence were headline news in what wascalled the “Red Summer.” A September 27 editorial in the Omaha World-Herald decried policeprotection, claiming that women and girls wereleft helpless. “Our women must be protected at allcosts,” the newspaper insisted. Omahans had beenreading for weeks, especially in the Bee, of policefailures to keep the peace, and shocking accountsof black men assaulting white women.In addition to the enmity aroused by putativerapes, racial tension was fueled by numerous additional sources of discontent. During the seconddecade of the twentieth century, societal turmoilaggravated race relations as thousands of blacksmigrated to the north in what was known as theSecond Great Exodus. (The first was 1870-79.) Omaha’s black population doubled from 5,143 in 1910to 10,315 in 1920.6 (Omaha’s 1920 white populationwas 191,601.) Wartime worker shortages in northerncities lured blacks seeking better paying jobs, better lifestyles, and the promise of freedom from JimCrow. Factory agents recruited black workers, paying railway or reduced fares and offering unskilledjobs with railroads and meat-packing plants.The 1918 armistice quieted the guns in Europe,but hostilities increased on the home front. Laborunrest was widespread. White union membersstriking for recognition and higher wages confronted black strikebreakers, exacerbating racialanimosities. The teamsters went on strike in June1919, and bricklayers, street and railway workers,and others followed, mostly failing to reach theirgoals. The Central Labor Union unsuccessfullyfall/winter2010 155

Rioters on the south sideof the courthouse. NSHSRG2281-72156tried to organize a general strike in Omaha, wherepolice claimed that agents of the Industrial Workersof the World were forming a committee to work forthe impending strike. Rumors circulated of blackstrikebreakers to be imported from East St. Louis.7Returning veterans seeking jobs in a tightenedemployment market discovered a “New Negro,”one anticipating that long-endured indignitiesand denial of rights would now pass into history.The war to make the world safe for democracyhad been won, but black Americans found theirown situation largely unchanged in their postwarworld. President Woodrow Wilson had even senta representative to France to warn black troopsnot to expect French democracy when theyreturned home.8Discontent grew in the black community. InOmaha and elsewhere, jobs open to blacks offeredlow wages, were concentrated in packing plants nebraska historyand railroads, and involved servile positions asporters, janitors, and waiters. Segregated neighborhoods offered substandard housing and minimalstreets and amenities. Low wages made utilities unaffordable.9 Prejudice, intolerance, and frustrationin the white community flourished amid a mindsetof white superiority and a conviction that blacksshould be submissive and “know their place.”A potent and combustible component of theracial divide was sex—the longstanding notion ofblack men preying on white women. A day beforeBrown’s lynching, U.S. Senator John Sharp Williams proclaimed that “the protection of a womantranscends all law of every description, human ordivine,” legitimizing the mostly sex-related lynchings of African Americans.10 Fifty-four blacks werelynched in the United States in 1916; by 1920 theannual number had grown to eighty-three.

Widespread violence erupted in some twentyfive U.S. cities during the “Red Summer” of 1919.Over one hundred blacks lost their lives in theseclashes, including thirty-six in Chicago, wherethousands were injured or left homeless.11 Whilethere are several identifiable causes of the riots,one is granted first place: sensation-seekingnewspapers. Stories of racial violence and lynching dominated headlines; especially provocativewere reports of white women assaulted by blacks,which were presented in stories that condoned thelynching and mob brutalities. The result was anatmosphere receptive to rabble rousing and tolerant of violence.12Adding to Omaha’s disquiet and distrust wasa political battle between a recently elected cityreform movement and an entrenched political machine eager to regain control by demonstrating theineptness of the reformer “goo-goos.”In its alliance with Tom “the Old Man” Dennison,Omaha’s powerful political boss, the Omaha Beewas the primary strident voice of alleged raciallyshocking crimes. Alarmed at the Bee’s promotionof violence and racial prejudice, the Rev. John A.Williams—first president of the local chapter ofthe NAACP and publisher of the Monitor, a weeklyblack paper—called upon the editors of the Beeand the Daily News to stop their propaganda. TheBee was charged with being the mouthpiece of agang that ruled Omaha with the cooperation ofbehind-the-scene influentials who decided whoshould run for office, with Dennison’s organizationelecting them. In return, according to the source,Dennison received money and control of the policedepartment, juries, and the police court to protectthe city’s vice interests.13Dennison and Bee founder Edward Rosewaterforged their political alliance around 1900; afterEdward’s death in 1906, his son Victor sustainedthe paper’s pro-Dennison orientation. Thanks toDennison, James Dahlman served as mayor ofOmaha from 1906 to 1918, when he was defeatedby reform candidate Edward P. Smith. Reformadvocates—especially civic and church groups,inspired by wartime rhetoric of fighting for democracy and offended by city administrators’ toleranceof gambling, prostitution, and drinking in the ThirdWard—removed Dennison’s allies from city hall.But his influence and connections with the Beecarried on. The police department commissioner,J. Dean “Lily White” Ringer, devoted to “cleaningup” the city, was stymied by a police departmentlittle interested in his puritanical ambitions. A presscampaign led by the Bee attacked city government,Bullet holes in thetreasurer’s office window.NSHS RG2281-74assailing it for rising crime and inefficiency. Citycommissioners were hobbled by the intramuralcontest between “moderate” reformers, whose goalwas “good” structures for governing the city, andthe radical reformers intent on cleansing it.14Omahans perceived their governance and safetyas unsatisfactory, and looked back to the yearswhen Dennison “kept the lid on.” Vicious politics,racial intolerance, black migration, alarmist sexstories, labor unrest, housing and employmentshortages, dissatisfaction with city governance,all vied for redress. City elections were but twoyears away.When he was taken to thecounty jail, Brown said he was working as a coalhustler (carrying coal from truck to cellars), andlimping because of rheumatism.15 Other sourceshave him employed in a packinghouse or in a lumberyard, suggesting heavy labor. However, a seriesof comments were made attesting to Brown’s physical limitations. A physical examination showedBrown was “too twisted by rheumatism to assaultfall/winter2010 157

From Omaha’s Riot in Storyand Picture.158anyone.” An unidentified Omaha World-Heraldreporter allegedly interviewed Brown in jail and“confirmed by his observation the man’s crippledcondition.” His chronic rheumatism meant Brownwould be unable to overpower Loeback andHoffman, concluded Jim McKee, a LincolnJournal writer.Subsequent accounts have frequently alluded toan unnamed lawyer who commented on Brown’sphysical limitations. For example, George Leighton in his 1938 Five Cities (and likely a source forothers to follow), states that a lawyer examinedBrown and “he found the man badly twisted withrheumatism and wondered how anyone in such acondition could have assaulted anyone.”16 Duringa WPA interview on November 11, 1938, Harrison J.Pinkett, a prominent African American Omaha attorney, said that he was the lawyer “that examinedWill Brown and he definitely states that it wouldhave been impossible for him to attack anyone.He states that it was merely an administration fightand Tom Dennison’s way of fighting Ed Smith andhis administration”17Ironically, Hoffman was repeatedly mentionedin the press as a cripple. He denied that description, saying he had a disability because of achildhood broken leg that never mended properly.18At about 2:00 p.m. on September 28, Hoffmanexhorted about two hundred mostly young peopleat Bancroft School to follow him to the courthouseand seize Brown. (Times and numbers given areapproximate.) Detective John Dunn told the marchers to halt, but they ignored him, their numbersincreasing as they passed. By 4:00 p.m., several nebraska historyhundred people had gathered at the south side ofthe courthouse, bantering with thirty policemenwho formed a cordon around the building. Thinking there was no threat, a police captain sent homefifty officers who had been summoned to policeheadquarters as a reserve.The crowd grew. Sixteen-year-old William Francis, who became known as “the boy on the horse,”rode with a rope on his saddle pommel, leadingpart of the crowd. Policemen ordered him severaltimes to leave, but he kept returning. Another agitator was William Sutej; a third was Claude Nethaway,who urged the crowd “to get the nigger and lynchhim.”19 Within an hour police were confronted bysome 4,000 to 5,000 angry people throwing rocks atthe courthouse. The north doors gave way to whathad become rioters, and the police chased themfrom the building several times.The mob attacked the police a little after 5:00p.m. One officer was pushed through a glass door;two others became targets when they drew theirclubs. Fire hoses were turned on the mob but without effect. Stones and bricks broke almost everywindow on the south side of the courthouse. Thepolice tried to discourage the assault by firing theirrevolvers down elevator shafts, but this only madethe crowd even angrier. Mayor Ed Smith and Police Chief Marshall Eberstein arrived and enteredthe building to restore order. Instead the crowdbattered down a door, and Francis appeared withseveral men hanging onto his horse’s tail as he rodethrough the entryway.With the courthouse surrounded and breached,Police Chief Marshall Eberstein climbed to asecond-story windowsill to speak to a briefly quieted audience. But after only a few moments thecrowd began jeering and shouting and throwingrocks, one of which nearly hit him. Eberstein wasforced to retreat. City commissioner Harry B. Zimman tried to talk to the growing mob, only to bedrowned out by shouts of “Lynch the damn Jew.”He suffered a few blows before being helped backinside by friends. There were no rocks or jeers forthe words of mechanic John Thomas as he laudedthe protection of white women.The police cordon was forced, and officers’caps, badges, and revolvers taken from them.Blacks in the vicinity were beaten, as were whitesthat tried to help them. Most of the police retreatedinside the building by 7:00 p.m., joining SheriffClark and his half dozen deputies. Fire brokeout an hour later and a nearby filling station wasvandalized to provide fuel. Shots were fired, andpawnshops and the Walter G. Clark and Townsend

Gun Company were broken into for revolvers andrifles (the looted establishments later estimatedtheir losses at 20,000).Mayor Ed Smith came out the east doors onSeventeenth Street to confront the mob, callingupon them to let the law take its course. His appeal was short-lived. He was hit with a baseball bator other blunt object (a Leonard Weber later saidhe hit the mayor over the head with a gun) and adozen other blows.“No, I will not give up the man,” Smith said. “I’mgoing to enforce the law even with my own life.”The crowd took his words to heart, shouting “hanghim” and “string him up.” With a noose around hisneck, the mayor was dragged along Harney Streetto the Sixteenth Street traffic signal tower. Therope was thrown over a bar and tightened aroundSmith’s neck when Russell Norgaard saved the mayor’s life by removing the rope. (Emmett C. Hoctorwrites in a letter that a witness, requesting anonymity, identified his uncle, James P. Hoctor, as the manwho removed the rope from Smith’s neck.)20Police reinforcements arrived with drawnpistols, and State Agent Ben Danbaum (he hadbeen an Omaha police officer under the DennisonFrom Omaha’s Riot in Story and Picture.regime) drove an automobile to the traffic towerwith city policemen Al Anderson, Charles Van Deusen, and Lloyd Toland to rescue Smith. They tookthe unconscious mayor to the Ford Hospital.21Smith later said he was positive that a mannamed Davis was one of his assailants. Davis wascharged with assault to murder, to do great bodilyinjury, conspiracy to murder, unlawful assembly,and rioting. Davis claimed he was home during theriot, and was not convicted.From Omaha’s Riot in Storyand Picture.The mob rushed back to thecourthouse, and the riot escalated as more gasoline was thrown into the building. Spreading flamesforced the police to retreat to the second floor. Firemen brought hoses, which the crowd soon hackedto pieces. Rioters took the firemen’s ladders andused them to enter the courthouse’s broken second-story windows. While leading a charge up thestairs to reach Brown, sixteen-year-old Louis Youngwas shot and killed, one of three people to diethat day. Policemen and sheriff’s deputies took tothe fourth floor with flames and angry men belowthem. Someone shouted, “Let no one leave,” andarmed men were stationed at every exit door.Sheriff Clark led Brown and his 121 fellow prisoners to the roof, but bullets fired from nearbybuildings sent them back downstairs. Clark convinced the rioters on the stairs to allow femaleprisoners to leave. Officers and deputies begantelephoning their wives with parting words. Deputyclerk of the court Asel Steere, realizing that severallarge record books were threatened by the fire,made his way through an entrance and went tofall/winter2010 159

his office, where he carried several district recordbooks to a vault and safety. He led three woundedpolice officers into the vault, and then someoneslammed the door. Trapped in the blazing building,the men broke through a wall and escaped whilebeing shot at.Ten officers in Court House Court Room 1 onthe fourth floor were threatened by the flames, buttheir call for help was refused with calls of “Let ’emburn. Bring the nigger down with you and we’llhand you a ladder.” From the west side of the building, three slips of paper floated down. Scrawled onone of them was, “Judge says will give up Brown.He’s in the dungeon. There are 100 white prisonerson the roof. Save them.” Another message read,Detail of above photo.NSHS RG2281-69160 nebraska history“Come to the fourth floor of the building and wewill hand the nigger over to you.”22Ladders were placed against the west side of theburning courthouse, and two men, one with a rope,the other carrying a shotgun, rushed up a ladderto the second floor. From there they performed anacrobatic climb to reach Brown and his defenderstwo floors up. By now it was dark, and automobileheadlights illuminated the window ledges andcornices for their ascent, while about thirty riotersgroped their way through smoked-filled stairwaysto reach Brown. Then shouts and shots came fromthe building’s south side. Brown was in the handsof his executioners.Accounts differ on how Brown ended up inthe hands of the rioters. Sheriff Clark claimed hesurrendered Brown to save the lives of the policeofficers and deputies, fearing they would be killedif the struggle continued. In another version, theblack prisoners grabbed Brown and turned himover, shouting, “Here is your man.” The day afterthe riot a youngster said he read the note that urgedothers to come to the fourth floor and “get the nigger.” With two friends he followed the instructionsand somebody handed Brown over to the thirtymen who had come up the stairs. “They tied a ropearound his neck and dragged him to the south sideof the building.”23

Beaten and bloody, he was taken downstairsand handed over to the waiting horde, anxious tohang him from the traffic tower at Eighteenth andHarney. Several men pulled Brown’s body intothe air as the crowd cheered. The swaying bodybecame a target for gunfire. Lowered after twentyminutes, Brown’s remains were tied to the end ofa police car that the mob had seized, and draggedto Seventeenth and Dodge streets. There he wasburned on a pyre fueled with oil from the red signal lanterns used for street repair. Brown’s charredremains were then dragged behind an automobilethrough downtown streets.Estimates of the crowd varyfrom 5,000 to 20,000. As it dwindled, U.S. troopsbegan arriving in response to requests for assistance. Earlier in the day, Chief Eberstein had calledCouncil Bluffs, Iowa, Chief of Police J. C. Jensen forassistance. Jensen replied he had no right to sendhis men out of the state. Omaha city officials askedthe Lancaster County Home Guard for help, butthe riot would be over before it could respond.24When Lt. Col. Jacob Wuest at Fort Omaha receiveda report that a riot was underway at the DouglasCounty Courthouse, he told Omaha’s police chiefthat federal troops could not get involved unless ordered by the War Department. The military’s chainof command had to be initiated, delaying actionwhile communication passed from Secretary ofWar Newton D. Baker down to the fort’s commanding officer. Not until 10:45 p.m. was the Fort Crookcommanding officer authorized to lend all possibleassistance to Omaha’s police.Colonel Wuest ordered two companies (sixofficers and 206 enlisted men) to the courthouseto restore order, and sent a third company to theblack district as a precaution. While the troopsmarched, Brown was being lynched, burned, andhis body dragged around the city’s downtownstreets. Another detachment was added a littlelater, so that a total of 320 soldiers were patrollingthe streets by 2:00 a.m. About the same time a localcommander in Omaha reported to Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, Commander of the Central Departmentof the Army, “all quiet in Omaha,” where rifles andmachine guns kept the peace.During the day special trains brought reinforcements from army camps in Iowa, Kansas, andSouth Dakota, to place 1,600 troops on duty inOmaha World-Herald,September 29, 1919fall/winter2010 161

Wreckage in Judge Sears’soffice. NSHS RG2281-73162Omaha. On the thirtieth, General Wood arrived inOmaha to organize his command: three companysize units were assigned to protect the courthouse,city hall, two black areas at Twenty-Fourth andLake Streets, Twenty-Fourth and O in South Omaha, plus a reserve unit at the city auditorium. Allbut two companies left Omaha on October 17. Theremaining federal troops on riot duty were withdrawn on November 15.The courthouse was in ruins. Completed in1912 at a cost of 1,500,000, damage to the building was estimated at 1,000,000; tax records wereburned, as were land indexes in the office of theregister of deeds. The county clerk’s office wasgutted, and furnishings and equipment in otheroffices a shambles.Three men were killed as victims of the mob’sfury: William Brown; teenager Louis Young, shotin the heart leading rioters up a stairway; and H. J.Hykell, a businessman shot in the abdomen whilewalking two blocks away. Fifty-some individuals were injured with cuts, bruises, beatings, andsmoke inhalation. County Attorney Abel Shotwellproclaimed the law would be enforced and the rioters prosecuted.Fifteen men, whose names were drawn bychance from a county voting list, took the grandjury’s oath on October 8, 1919. Sheriff Clark selecteda sixteenth, Henry W. Dunn, a Dennison loyalist and former chief of police who later becamecommissioner of police. October and Novemberindictments included counts of murder with revolvers, hanging, striking, beating, bruising, wounding, nebraska historyshooting, choking, strangling and suffocatingBrown, along with arson, breaking and entering,and inciting others to the same acts.The grand jury issued 189 indictments. Twelveyear-old Sol Francis was the youngest to bearrested; he had urged other rioters to follow himas he climbed a ladder. Only a few of the arrestedwere ever prosecuted, mostly on minor charges.Two exceptions were Ralph Snyder and ClaudeNethaway, both charged for Brown’s murder. Theywere found not guilty after brief jury deliberation.From atop a burned police car, Snyder had shouted, “We have showed the nigger what a northernmob can do.”25Six weeks of deliberations culminated with thegrand jury’s report, submitted by its foreman, JohnW. Towle, who lamented obstacles to their investigations, including uncooperative eyewitnesses. Thereport attributed the riot to multiple causes, whichwere similar to those cited after “Red Summer” riotsin other cities: unmentionable assaults on females;contempt for authority and laws; economic conditions; strikes and lockouts; unsettled soldiers; classhatred; and social unrest. Bolsheviks, sovietism,and anarchists took advantage of these conditionsto provoke a riot and bring down the city’s government. Absent from the list is racism.26Milton Hoffman disappearedafter the riot. He went to Denver, where he marriedAgnes, later returning to Omaha where he spent therest of his life.27 Denver was the home of Dennison’sfriend Vaso Chucovich, and Hoffman was, in fact,Dennison’s employee. His uncle had recommendedhim to the “Old Man” a few years earlier after theteenage Hoffman completed a business course. Heworked as Dennison’s secretary, assisting with election ballots and voting before he was twenty-one.Though he had left Omaha to travel, he returnedprior to the riot.28Collusion between Dennison and the Bee is frequently identified as the prime immediate cause ofthe riot. The alleged goal of the longtime allies wasto poison an already volatile environment by discrediting the Smith reformers so as to ensure theirdefeat in the election.29The grand jury report said people in the mobwere under the influence of liquor, but lamentedit had no evidence of drinking or drunks. Rumorfilled in where verification was lacking; storiesspread of liquor distributed throughout the city,with unlimited quantities available at the courthouse. The courthouse gang urged the crowd to“drink up” and spur enthusiasm for the task at

hand. Another story was that taxicabs weremade available to bring people to the scene andto take the wounded away. Many people believedthat accounts of black rapists were actually whitemen in blackface.Some denied Dennison’s involvement. “Dennison never had anything do with that riot,” claimeda former police officer, adding it was “a bunch ofpunks” who started it and it kept getting biggerand bigger. Another person recalled that kids wereresponsible, and Dennison didn’t know about it.Dennison stalwart William “Billy” Maher deniedthe “Old Man” had anything to do with the riot, butadded, “I don’t say he didn’t get a kick out of it, theway it ruined the administration that was in.”30There is no evidence to prove Tom Dennison’sdirect involvement in Brown’s death, but his longtime relationship with the Bee’s Rosewaters, hiscampai

divine,” legitimizing the mostly sex-related lynch-ings of African Americans.10 Fifty-four blacks were lynched in the United States in 1916; by 1920 the annual number had grown to eighty-three. Rioters on the south side of the