Transcription

Persuasion: EmpiricalEvidenceStefano DellaVigna1 and Matthew Gentzkow21Department of Economics, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, andNBER; email: sdellavi@berkeley.edu2Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, andNBER; email: gentzkow@chicagobooth.eduAnnu. Rev. Econ. 2010. 2:643–69Key WordsFirst published online as a Review in Advance onMay 7, 2010communication, beliefsThe Annual Review of Economics is online atecon.annualreviews.orgThis article’s ht 2010 by Annual Reviews.All rights reserved1941-1383/10/0904-0643 20.00AbstractWe provide a selective survey of empirical evidence on the effects aswell as the drivers of persuasive communication. We consider persuasion directed at consumers, voters, donors, and investors. Weorganize our review around four questions. First, to what extentdoes persuasion affect the behavior of each of these groups? Second, what models best capture the response to persuasive communication? Third, what are persuaders’ incentives, and what limitstheir ability to distort communications? Finally, what evidenceexists on the way persuasion affects equilibrium outcomes in economics and politics?643

1. INTRODUCTIONThe efficiency of market economies and democratic political systems depends on theaccuracy of individuals’ beliefs. Consumers need to know the set of goods available andbe able to evaluate their characteristics. Voters must understand the implications of alternative policies and be able to judge the likely behavior of candidates once in office.Investors should be able to assess the expected profitability of firms.Some beliefs are shaped by direct observation. But a large share of the information onwhich economic and political decisions are based is provided by agents who themselveshave an interest in the outcome. Information about products is delivered through advertising by the sellers, political information comes from candidates interested in winningelections, and financial data are released strategically to shape the perceptions of investors.Third parties that might be more objective—certifiers, media firms, financial analysts—have complex incentives that may diverge from the interests of receivers.Scholars have long theorized about the implications of communication by motivatedagents. Some have seen persuasion as a largely negative force, with citizens and consumerseasily manipulated by those who hold political or economic power (Lippmann 1922,Robinson 1933, Galbraith 1967). Others have been more positive, seeing even motivatedcommunications as a form of information that can ultimately increase efficiency (Bernays& Miller 1928, Downs 1957, Stigler 1961).In this review, we provide a selective survey of empirical evidence on the effects as well asthe drivers of persuasive communication. We define a persuasive communication to be amessage provided by one agent (a sender) with at least a potential interest in changing thebehavior of another agent (a receiver). We exclude situations in which an agent attempts tomanipulate another through means other than messages—providing monetary incentives, forexample, or outright coercion. We also depart from some existing literatures in using the termpersuasion to refer to both informative and noninformative dimensions of messages.Some of the evidence we review comes from economists, including a recent surge ofwork applying modern empirical tools. Other evidence comes from marketing, politicalscience, psychology, communications, accounting, and related fields. Our main focus is onstudies that credibly identify effects on field outcomes. We do not attempt to review thelaboratory evidence on persuasion. Even within these parameters, we inevitably omit manyimportant studies and give only cursory treatment to others.We consider four groups that are targets of persuasion: consumers, voters, donors, andinvestors. We organize our review around four questions. First, to what extent does persuasion affect the behavior of each of these groups? Second, what models best capture theresponse to persuasive communication? In particular, we distinguish belief-based modelsfrom preference-based models. Third, what are persuaders’ incentives, and what limitstheir ability to distort communications? Finally, what evidence exists on the equilibriumoutcomes of persuasion in economics and politics?2. HOW EFFECTIVE IS PERSUASION?A large portion of the literature on persuasion is concerned with measuring the effect ofpersuasive communications on behavior. Credibly measuring the direct effect of persuasionis interesting in its own right, and it is also an input to better understand when and wherepersuasion is effective, what models best explain receivers’ reactions, and so on.644DellaVigna Gentzkow

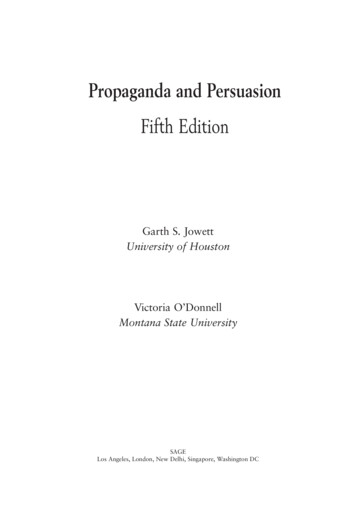

The estimates of the effectiveness of persuasion, however, are hard to compare. Thestudies on persuasion adopt a variety of empirical methodologies—natural experiments,field experiments, and structural estimates, among others—and outcome variables, insettings as diverse as advertising campaigns and analyst recommendations.In this section, we provide a unified summary of some of the best existing evidenceacross the different areas mentioned above. Whenever possible, we report the results interms of the persuasion rate (DellaVigna & Kaplan 2007), which estimates the percentageof receivers that change the behavior among those that receive a message and are notalready persuaded. We summarize persuasion rates for the studies we review in Table 1.[The Supplemental Appendix details the calculation of the persuasion rate for each study(follow the Supplemental Material link from the Annual Reviews home page at http://www.annualreviews.org).]In a setting with a binary behavioral outcome, a treatment group T, and a control groupC, the persuasion rate f (in percent terms) isf ¼ 100 yT yC 1,eT eC 1 y0ð1Þwhere ei is the share of group i receiving the message, yi is the share of group i adopting thebehavior of interest, and y0 is the share that would adopt if there were no message. Wherey0 is not observed, we approximate it by yC.1The persuasion rate captures the effect of the persuasion treatment on the relevantbehavior (yT yC), adjusting for exposure to the message (eT eC) and for the size of thepopulation left to be convinced (1 y0). For example, suppose that get-out-the-vote(GOTV) mailers sent to the treatment group increase turnout by 1 percentage point relativeto the control group. The size of this effect may suggest that mailers are not very persuasive. However, the implied persuasion rate can in reality be high if, say, only 10% of votersin the treatment group received a GOTV mailer (eT eC is small) and the targetedpopulation already had high turnout rates of 80% (1 y0 is small). In this case, the impliedpersuasion rate is f ¼ 100 (0.01)/(0.1 0.2) ¼ 50%. If the persuadable population issmall, a small change in behavior can imply a high impact of persuasion.We do not claim that the persuasion rate is a deep parameter that will be constant eitherwithin or between contexts. It captures the average rather than the marginal effect ofpersuasion and will depend, for example, on the quality of messages, the incentives ofsenders, the prior beliefs of receivers, and the heterogeneity in the population. Nevertheless, the normalization in Equation 1 puts studies on more equal footing and makes iteasier to isolate the role of determinants of persuasive effects.2.1. Persuading ConsumersThe first form of persuasion we consider is communication directed at consumers. Moststudies in this domain focus on communication from firms in the form of advertising. Thebehavioral outcome is typically purchases or sales volume.Some of the earliest studies of advertising effects exploit messages that can be linkeddirectly to receiver responses. Shryer (1912), for example, places classified ads for a mail1Assuming random exposure and a constant persuasion rate f, the share in group i who adopt the behavior is yi ¼y0 þ eif(1 y0). Rearranging this expression gives Equation 1. Solving the system for y0, one obtains y0 ¼ yC eC(yT yC)(eT eC). The approximation y0 ¼ yC is valid as long as the exposure rate in the control group is small (eC 0)or the effect of the treatment is small (yT yC 0).www.annualreviews.org Persuasion: Empirical Evidence645

646DellaVigna Gentzkow(1)get-out-thevote (GOTV)2000 (FE)olds18–30-year-Phone callsyouth vote2001 (FE)Phone calls byGerbercanvassing2008 (FE)Green &Door-to-doorGreen et al.1–3 cardsmailing ofGOTVcanvassingDoor-to-doorGreenof registrationGerber &Card reminding1926No GOTVNo GOTVNo GOTVNo GOTVNo GOTVNo cardinterest raterateGosnell6.5%Mailer withphotoMailer no12 catalogs(2)Control4.5% interestMailer withfemale photoMailer withcatalogs sent17 clothingPersuading voters(FE)et al. 2010Bertrand(NE)et al. 2007SimesterPersuading consumersPaperTreatmentTable 1 Persuasion rates: summary of studieselectionGeneralelectionGeneralLocal outh AfricaLoan offer TurnoutRegistrationloanApplied for 1 itempurchasingShare(4)Variable t2000200020011998192420032002(5)Yeartwo citiesVoters infour citiesVoters incitiesVoters in sixvotersNew HavenvotersChicagobankclients pients (6)Few daysFew daysFew daysFew days1 month1 yearN ¼ 4,278N ¼ 4,377N ¼ 18,933N ¼ 29,380N ¼ 5,700N ¼ 53,194N ¼ 10,000N ¼ .8%33.9%(10)tCgroup tTSample 9.3%100% 27.9%100.0%100% 100% 100% 100% %4.2%(12)rate f(11)PersuasionrateeT eCExposure

www.annualreviews.org Persuasion: Empirical Evidence647Availability ofFox news viacableDellaVigna& Kaplan(2007)independentanti-Putin TVet al. 2010(NE)endorsements2009 (NE)newspaperRead localtelevisionExposure tolow seedReiley2002 (FE)mailer withFund-raiserLucking-List &Persuading donors2009 (NE)& ShapiroGentzkow2006 (NE)GentzkowNo mailerpaperNo localNo televisioncomputer labCampaign hare givingTurnoutTurnoutsurvey)Post(stated inWashingtonvote shareDemocraticto TheelectionGovernorGoreSupport forpartiesanti-PutinVote share ofvote shareRepublican(4)Variable tionFree orsmentsNoNo NTVcableNetwork viaNo Fox(2)Controlet al. 2009GerberDemocraticKnight(NYT)UnsurprisingChiang &station (NTV)Availability ofEnikolopov(NE)(1)Treatment(Continued)PaperTable ��(5)YearFlorida donorscountiesAll U.S.countiesAll U.S.Virginiacitiesin fourVotersvotersRussianStates28 U.S.Recipients (6)1–3 weeks0–4 years10 years2 monthsweeksFew3 monthsN ¼ 1,000million N ¼ 100million N ¼ 100N ¼ 1,011N ¼ 32,014millionN ¼ 453.7%70.0%54.5%67.2%55.1%75.5%17.0%56.4%N ¼ 66million(9)(8)(7)0–4 yearstCgroup tTSample 0)groupControlTreatmentTime100% %12.9%4.4%19.5%þ6.5%2.0%7.7%þ11.6%þ(12)rate f(11)PersuasionrateeT eCExposure

648DellaVigna Gentzkowcampaign for(FE)campaign for(FE)(4 postcards)Mailer with giftno giftmailer withFund-raisercharityin local paper2009 (NE)No coverageNo mailerNo mailerNo visitNo visitNo mailer(2)ControlshareTrading ofNo giftCampaignCampaign(3)Contextnewsstock inshares ofTrading ofmoneyShare givingmoneyShare givingmoneyShare giving(4)Variable t19961991–200420082004(5)YearbrokerageInvestors inSwiss ients (6)3 days1–3 weeksImmediateImmediateN ¼ 15,951N ¼ 3,347N ¼ 3,262N ¼ 946N ¼ 4,833N ¼ 0%0%0%(10)tCgroup tTSample sizehorizon(9)groupControlTreatmentTime60.0%100% 100% 41.7%36.3%100% 0.010%20.6%12.2%11.0%29.7%8.2%(12)rate f(11)PersuasionrateeT eCExposureNotes: Calculations of persuasion rates by the authors. The list of papers indicates whether the study is a natural experiment (NE) or a field experiment (FE). Columns 9 and 10 report the value of thebehavior studied (column 4) for the treatment and control group. Column 11 reports the exposure rate, that is, the difference between the treatment and the control group in the share of peopleexposed to the treatment. Column 12 computes the estimated persuasion rate f as 100 (tT tC)/[(eT eC)(1 tC)]. The persuasion rate denotes the share of the audience that was not previouslyconvinced and that is convinced by the message. The studies in which the exposure rate (column 11) is denoted by 100% are cases in which the data on the differential exposure rate betweentreatment and control are not available. In these case, we assume eT eC ¼ 100%, which implies that the persuasion rate is a lower bound for the actual persuasion rate. In the studies on persuadingdonors, even in cases in which an explicit control group with no mailer or no visit was not run, we assume that such a control would have yielded tC ¼ 0% because these behaviors are very rare in theabsence of a fund-raiser. For studies with vote share as a dependent variable (denoted with a þ), see the Supplemental Appendix for details on how the persuasion rate is calculated and for additionaldetails (follow the Supplemental Material link from the Annual Reviews home page at http://www.annualreviews.org).earnings newsCoverage of& ParsonsEngelbergPersuading investors(FE)Falk 2007fund-raisinget al. sityfund-raisingDoor-to-doorhigh seedmailer withFund-raiser(1)Treatment(Continued)et al. 2006LandryPaperTable 1

order business that include a code customers use when they reply. He compiles data on theresponse rates of each ad he placed and analyzes their relative effectiveness and the extentof diminishing returns.Field experiments have long been used to study advertising effects, with many studiescarried out by advertisers themselves. Hovde (1936), for example, discusses splitrun experiments conducted in cooperation with the Chicago Tribune in which groups ofsubscribers are assigned to receive different advertising inserts in their Sunday papers.Similar split-run tests are discussed by West (1939), Zubin & Peatman (1943), andWaldman (1956). Ackoff & Emshoff (1975) report on one of the earliest television advertising experiments—a series of tests carried out by Anheuser-Busch between 1962 and1964 in which different markets are assigned different advertising levels. A large numberof other market-level and individual-level experiments have been carried out subsequentlyand reported in the marketing literature.Overall, these studies provide little support for the view that there is a consistent effectof advertising spending on sales. The Anheuser-Busch studies find that both increasing anddecreasing advertising increased sales; these results led the firm to significantly cut advertising in most of its markets. Aaker & Carman (1982) and Lodish et al. (1995) review largenumbers of experiments and conclude that a large share of ads have no detectable effect.Hu et al. (2007) is the only review of experimental evidence that detects positive effects ofadvertising spending on average.2Several recent papers by economists use field experiments to estimate the effect of persuasive communication on sales. The results, like those in the marketing literature, are mixed.Simester et al. (2007) vary the number of catalogs individuals receive by mail from a women’sclothing retailer. They find that increasing the number of catalogs in an 8-month period from12 to 17 increases the number of purchases during the test period by 5% for customers whohad purchased frequently in the past and by 14% for those who had purchased relativelyinfrequently. The effect on the extensive margin (the share of customers who purchase at leastone item) implies a higher persuasion rate for the frequent buyers (f ¼ 6.9) than for the lessfrequent buyers (f ¼ 4.2) (Table 1).3 Lewis & Reiley (2009) report the results of an onlineadvertising experiment involving more than a million and a half users of Yahoo! whosepurchases were also tracked at a large retailer. Of the subjects in the treatment group, 64%were shown ads. The purchases of the treatment group were 3% greater than the purchasesof the control group, but this difference is not statistically significant. Bertrand et al. (2010)randomize the content of direct-mail solicitations sent to customers of a South Africanlender. They vary the interest rates offered, as well as the persuasive features of the mailer,such as the picture displayed or the number of example loans presented. Some features ofthe mailers—the picture displayed, for example—do have large effects on loan takeup,whereas others do not—comparisons with competitors, for example.A final body of evidence on advertising effects exploits naturally occurring variation.Bagwell (2007) reviews the large literature studying correlations between monthly or2The results of all these studies must be interpreted with caution because the assignment to treatment and controlconditions is often not randomized explicitly, and because the reported results often lack sufficient detail to assess thequality of the statistical analysis. Nevertheless, the negative results are striking given that the most obvious biaseswould tend to overstate the effect of advertising.3In this case, we do not observe how many of the customers in the treatment group received and read the catalogs;that is, we do not observe eT. In this and in similar subsequent cases, we assume eT eC ¼ 1, hence providing a lowerbound for the persuasion rate.www.annualreviews.org Persuasion: Empirical Evidence649

annual measures of aggregate advertising intensity and sales. These studies frequently findlarge advertising effects, although the endogeneity of advertising expenditure makesinterpreting the results difficult. A more promising approach is to exploit high-frequencyvariation in advertising exposure. Tellis et al. (2000), for example, analyze data from acompany that advertises health care referral services on television, examining calls fromcustomers to an 800 number listed on the screen. Under the assumption that customerswho are persuaded by the ad call the 800 number in a short window of time, these dataallow valid estimation of advertising effects. The authors find that an additional televisionad in an hour time block generates on the order of one additional call. Similar assumptionsjustify studies by Tellis (1988) and Ackerberg (2001) who use high-frequency individuallevel supermarket purchase data matched to individual-level advertising exposures. Thelatter study finds that an exposure to one additional commercial per week has the sameeffect on purchases of an average inexperienced household as a 10-cent price cut.2.2. Persuading VotersA second form of persuasion is communication directed at voters. Such communicationsmay come from politicians themselves, interested third parties such as GOTV organizations, or the news media. The relevant behaviors include the decision to vote or not and theparty chosen conditional on voting.Early studies of political campaign communications find little evidence of effects onvoters’ choice of candidates. Lazarsfeld et al. (1944) and Berelson et al. (1954) track thevoting intentions and political views of survey respondents over the course of presidentialcampaigns. They find that after months of exposure to intensive political communications,most respondents are more convinced of the political views with which they began. Summarizing this and other survey-based research, Klapper (1960, p. 50) writes “[R]esearchstrongly indicates that persuasive mass communication is. . . more likely to reinforce theexisting opinions of its audience than it is to change such opinions.” For several decadessubsequently, the consensus in political science and psychology was that political communication had “minimal effects” (Gerber et al. 2007).More recent studies have identified stronger correlations between exposure to politicalcommunications and voting. Iyengar & Simon (2000) and Geys (2006) review this literature, which for the most part lacks compelling strategies for identifying causal effects. Anexception is a field experiment on the effects of political advertising by Gerber et al.(2007). Working with a gubernatorial campaign in Texas, the authors randomly assignmarkets to receive an ad campaign early or late. Using a daily tracking survey of voters’attitudes, the authors find strong but short-lived effects of television ads on reportedfavorability toward the various candidates.A separate literature examines the impact of GOTV operations. Among the earlieststudies, Gosnell (1926) provided a reminder card stating the necessity of registration to atreatment group of 3,000 and no card to a control group of 2,700 voters. This cardincreased the registration rate from 33% in the control group to 42% in the treatmentgroup, implying a persuasion rate of f ¼ 13.4.Building on these early studies, Gerber, Green, and coauthors run a series of GOTVfield experiments (see Green & Gerber 2008 for a quadrennial review of this literature). Inmost of these experiments, households within a precinct are randomly selected to receivedifferent GOTV treatments right before an election; the effects are measured using the650DellaVigna Gentzkow

public records of turnout, which can be matched ex post to the households targeted.Gerber & Green (2000) show that door-to-door canvassing increases turnout from 44.8%to 47.2% in a New Haven congressional election (f ¼ 15.6). Mailing cards with the sameinformation has a much smaller effect (f ¼ 1.0). Green et al. (2008) find large effects ofdoor-to-door campaigning in 2001 local elections (f ¼ 11.5), and Green & Gerber (2001)demonstrate large effects of personal phone calls in the 2000 election (f ¼ 20.4 in onesample and f ¼ 4.5 in another). (The effect of phone calls from marketing firms is muchsmaller.) The remarkable effectiveness of a brief personal contact indicates how malleablethe turnout decision is.Beyond the literature on direct political communication, a number of recent papersfocus on the effect of the news media. Four papers consider the role of partisan media onvote share: Two papers exploit idiosyncrasies of media technology that lead to variation inavailability, one paper uses the precise timing of media messages, and a last paper uses afield experiment. DellaVigna & Kaplan (2007) exploit idiosyncratic variation in whethertowns had Fox News added to their cable systems between 1996 and 2000. They find thatFox News availability increased the presidential vote share of Republicans in 2000 by halfa percentage point, implying a persuasion rate of f ¼ 11.6 of the audience that was notalready Republican.4 Enikolopov et al. (2010) use a related method to show that Russianvoters with access to an independent television station (NTV) were more likely to vote foranti-Putin parties in the 1999 parliamentary elections (f ¼ 7.7). Chiang & Knight (2009)use daily polling data to show that in the days following the publication of a newspaperendorsement for president, stated voting intentions shift toward the endorsed candidate(f ¼ 2.0 for the unsurprising endorsement for Gore of The New York Times and f ¼ 6.5 forthe surprising Gore endorsement of The Denver Post). Gerber et al. (2009) use a fieldexperiment to estimate the effect of partisan media coverage. They randomly assign subscriptions to a right-leaning newspaper (The Washington Times) or a left-leaning newspaper (The Washington Post) to consumers in northeastern Virginia one month beforethe November 2005 Virginia gubernatorial election. They find no significant effects onmeasures of political information or attitudes, but they do detect an increase in selfreported votes for the Democratic candidate among those assigned to The WashingtonPost (f ¼ 20.0).These studies imply a wide range of treatment effects of media exposure on vote share,with the effect of The Washington Post (11.2 percentage points) 28 times larger than theeffect of Fox News (0.4 percentage points). Once we take account of differences in theshare of subjects exposed to treatment, however, the effects are more similar, with persuasion rates for the main treatments of interest ranging from 6% to 20%.A second set of papers on media effects considers the impact of the media on voterparticipation. Gentzkow (2006) uses a natural experiment—the diffusion of television inthe 1950s—to study the effects of television access on voter turnout. Comparing observably similar counties that received television relatively early or relatively late, he finds thattelevision reduced turnout by 2 percentage points per decade for congressional elections(f ¼ 4.4) but had no significant effect for presidential turnout. He argues that substitutionaway from newspapers and radio (which provide relatively more coverage of local news)4The persuasion rate for vote share as an outcome variable acknowledges that the message can cause party switchesor turnout changes (see the Supplemental Appendix for the expression; follow the Supplemental Material link fromthe Annual Reviews home page at g Persuasion: Empirical Evidence651

provides a plausible mechanism. Gentzkow & Shapiro (2009) exploit sharp timing toestimate the effect of newspaper entries and exits on voting using data from 1868 to1928. They find that the first newspaper in a county significantly increases voter turnoutby 1 percentage point (f ¼ 12.9). In contrast to the studies above, they find that partisannewspapers do not have significant effects on the share of votes going to Republicans.A possible reconciliation is that voters filter out bias for media that explicitly state theirpartisan affiliations, as newspapers did in the period 1868–1928, but not for media thatclaim objectivity, as in the modern media context.2.3. Persuading DonorsA third form of persuasion is communications from nonprofits or charities to solicit contributions. The outcome measures are monetary donations or nonmonetary contributions,such as of time or blood.Some of the earliest studies are in psychology and sociology and examine the determinants of blood donation, recycling, and helping decisions, often using experiments. Thesestudies document the importance of in-person contacts (Jason et al.1984) and the delicaterole of incentives in inducing prosocial behavior: For example, paying people to donateblood may reduce the donations because it crowds out intrinsic motivation (Titmuss 1971).Recently, two economists (Mellstrom & Johannesson 2008) test this hypothesis using afield experiment. Among women, offering a monetary compensation of approximately 7lowers the rate of blood donations from 51% in the control group (with no pay) to 30%.Turning to the studies of fund-raising and monetary donations, List & Lucking-Reiley(2002) send letters to raise funds for the purchase of computers for a center and randomizethe amount of seed money (the amount already raised) stated in the different letters. In thelow-seed treatment, 3.7% of recipients donate a positive amount, compared with 8.2% inthe high-seed treatment. One interpretation is that seed money serves as a signal of charityquality.Landry et al. (2006) conduct a door-to-door campaign to fund-raise for a capitalcampaign at East Carolina University. In their benchmark treatment (Table 1), 36.3% ofhouseholds open the door, and 10.8% of all households contacted (including the ones thatdo not open the door) donate, for an implied persuasion rate of f ¼ 29.7. DellaVigna et al.(2009) also conduct a door-to-door field experiment and find a sizeable persuasion rate off ¼ 11.0, even for a relatively unknown out-of-state charity. Falk (2007) shows that smallgifts can significantly increase donations. Solicitation letters for schools in Bangladeshinduced substantially higher giving if they were accompanied by postcards designed bystudents of the school (20.6% giving) than if they were accompanied by no postcard(12.2% giving).2.4. Persuading InvestorsThe fourth form we consider is communication directed at investors—by firms themselves(earnings announcements), by financial analysts (buy/hold/sell stock recommendations andearnings forecasts), or by the media. The function of analysts as a third party in financialcommunications is similar to that of the media in political communications. The outcomesin these studies are typically aggregate response of stock prices, or occasionally individualbehavior.652DellaVigna Gentzkow

An early event study examining investor response to earnings information is Ball &Brown (1968). Using the difference between current and previous annual earnings as ameasure of new information, the authors find a significant correlation with stock returns inthe two days surrounding the earnings release. More recent studies (see Kothari 2001 for areview) use the median analyst forecast (the so-called consensus forecast) to measureinvestor expectations and detect an even larger response to earnings news. Companies inthe top decile of earnings news experience on average a positive return of 3% in the twodays surrounding the release, compared with an average 3% return for companies in thebottom decile of news.5An early study of the impact of analyst recommendations is Cowles (1933). Using dataon 7,500 stock recommendations made by analysts in 16 leading financial services companies between 1928 and 1932, he estimates that the mean annual returns of following theanalyst

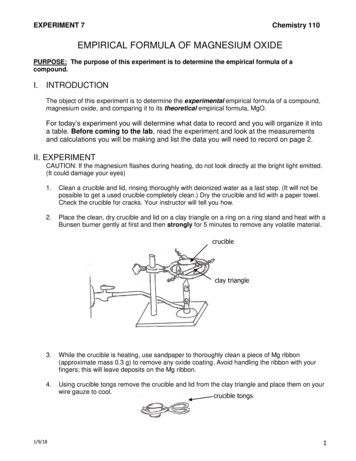

persuasion rate is f ¼ 100 (0.01)/(0.1 0.2) ¼ 50%. If the persuadable population is small, a small change in behavior can imply a high impact of persuasion. We do not claim that the persuasion rate is a deep parameter that will be constant either within or between contexts. I