Transcription

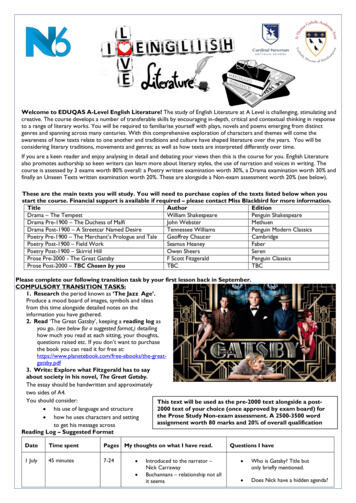

Welcome to EDUQAS A-Level English Literature! The study of English Literature at A Level is challenging, stimulating andcreative. The course develops a number of transferable skills by encouraging in-depth, critical and contextual thinking in responseto a range of literary works. You will be required to familiarise yourself with plays, novels and poems emerging from distinctgenres and spanning across many centuries. With this comprehensive exploration of characters and themes will come theawareness of how texts relate to one another and traditions and culture have shaped literature over the years. You will beconsidering literary traditions, movements and genres; as well as how texts are interpreted differently over time.If you are a keen reader and enjoy analysing in detail and debating your views then this is the course for you. English Literaturealso promotes authorship so keen writers can learn more about literary styles, the use of narration and voices in writing. Thecourse is assessed by 3 exams worth 80% overall: a Poetry written examination worth 30%, a Drama examination worth 30% andfinally an Unseen Texts written examination worth 20%. These are alongside a Non-exam assessment worth 20% (see below).These are the main texts you will study. You will need to purchase copies of the texts listed below when youstart the course. Financial support is available if required – please contact Miss Blackbird for more information.TitleAuthorEditionDrama – The TempestWilliam ShakespearePenguin ShakespeareDrama Pre-1900 – The Duchess of MalfiJohn WebsterMethuenDrama Post-1900 – A Streetcar Named DesireTennessee WilliamsPenguin Modern ClassicsPoetry Pre-1900 – The Merchant’s Prologue and TaleGeoffrey ChaucerCambridgePoetry Post-1900 – Field WorkSeamus HeaneyFaberPoetry Post-1900 – Skirrid HillOwen SheersSerenProse Pre-2000 - The Great GatsbyF Scott FitzgeraldPenguin ClassicsProse Post-2000 – TBC Chosen by youTBCTBCPlease complete our following transition task by your first lesson back in September.COMPULSORY TRANSITION TASKS:1. Research the period known as ‘The Jazz Age’.Produce a mood board of images, symbols and ideasfrom this time alongside detailed notes on theinformation you have gathered.2. Read ‘The Great Gatsby’, keeping a reading log asyou go, (see below for a suggested format,) detailinghow much you read at each sitting, your thoughts,questions raised etc. If you don’t want to purchasethe book you can read it for free atgatsby.pdf3. Write: Explore what Fitzgerald has to sayabout society in his novel, The Great Gatsby.The essay should be handwritten and approximatelytwo sides of A4.You should consider:This text will be used as the pre-2000 text alongside a post2000 text of your choice (once approved by exam board) for his use of language and structurethe Prose Study Non-exam assessment. A 2500-3500 word how he uses characters and settingassignment worth 80 marks and 20% of overall qualificationto get his message acrossReading Log – Suggested FormatDateTime spentPages My thoughts on what I have read.1 July45 minutes7-24 Introduced to the narrator –Nick CarrawayBuchannans – relationship not allit seemsQuestions I have Who is Gatsby? Title butonly briefly mentioned. Does Nick have a hidden agenda?

Wider Reading and Preparation for A-Level Task 1Why not watch a play online?Here are some of the places you can watch theatre online The National Theatre has created National Theatre Live:with a YouTube streaming schedule for free plays each ree-plays-eachthursday-050720 Digital Theatre also offers a wide range of plays to watch on-demand (including from the Royal ShakespeareCompany). Although this is a subscription site, some of the plays are available on their YouTube site. They arealso currently offering a 30-day free ttps://www.digitaltheatre.com/consumer/productions Shakespeare’s Globe also has a wide range of plays which can be rented or bought at:https://globeplayer.tv/allAlongside a range of free content: https://globeplayer.tv/free-contentA Shakespeare Play Choose a Shakespeare play you have never studied before. Watch the play online. Record a 2-minute review of it to send to your teacher.A play not Shakespeare! Enjoy watching the play. Write the script for a podcast/online discussion between acritic and a director about the play. You can see examples of this sort of discussion on thefollowing websites (all are freely accessible):1. National Theatre YouTube Channelhttps://www.youtube.com/playlist?list PLJgBmjHpqgs7citDojiasj-nMABL DXku2. National Theatre alks/id486761654?mt 23. Young Vichttps://www.youtube.com/playlist?list PLqth0oZ0oHJJYftVHd2ZHwaKQ shhRGhf4. Shakespeare’s kQegAHxyo2g5. egAHxyo2g

Wider Reading and Preparation for A-Level Task 2The Art of the review2000The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, Michael Chabon2001The Corrections, Jonathan FranzenAtonement, Ian McEwanThe Siege, Helen Dunmore2002If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things, Jon McGregor2003We Need To Talk About Kevin, Lionel ShriverThe Namesake, Jhumpa LahiriBrick Lane, Monica Ali2004Cloud Atlas, David MitchellThe Dew Breaker, Edwidge DanticatThe Man in My Basement, Walter MoselyKafka on the Shore, Haruki MurakamiSmall Island, Andrea Levy2005Never Let Me Go, Kazuo IshiguroOut Stealing Horses, Per Peterson2006The Road, Cormac McCarthyHalf of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi AdichieThis Book Will Save Your Life, A.M.HomesThe Book Thief, Marcus ZusackSuite Francaise, Irene Nemirovsky (year first published in English)Old Filth, Jane GardamWinter’s Bone, Daniel WoodrellWhat is the What, Dave EggersThe inheritance of Loss, Kiran Desai2007Persepolis, Marjane Sartrapi (the complete two volumes)The Song Before it is Sung, Justin CartwrightThe Road Home, Rose TremainThe Reluctant Fundamentalist, Mohsin HamidThe Girls, Lori LansensThe Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Junot Diaz2008The Rehearsal, Eleanor CattonOlive Kitteridge, Elizabeth StroutThe White Tiger, Aravind AdigaThe Vagrants, Yiyun Li2009Wolf Hall, Hilary MantelA Gate at the Stairs, Lorrie MooreLet the Great World Spin, Colum McCannBrooklyn, Colm Toibin2010A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan2011Ours are the Streets, Sunjeev SahotaA Monster Calls, Patrick NessSnowdrops, A.D. MillerThe Tiger’s Wife, Tea Obrecht2012NW, Zadie SmithLeaving the Atocha Station, Ben LernerThis is Life, Dan RhodesCanada, Richard FordThe Sisters Brothers, Patrick DeWittThe Panopticon, Jenni Fagan2013Life After Life, Kate Atkinson1. Choose one of the books from the list toread.2. Read three or four online reviews of the novelafter you have read it.Places to find reviews By writers, critics etc: Guardian, Independent,New York Times, Slate By readers: Amazon, GoodReads,LibraryThing, Book Riot.3. by thinking about your personal response tothese – is there one you feel more insympathy with, that captures what youthought and felt? Do you like thestyle/approach of one more than another?4. Then take a step back and look at each a bitmore clinically. What do each of the reviewersfocus on (the story, the characters, underlyingthemes, their personal response)? Whatapproach do they take to writing the review?5. Drawing on what you have learned about theart of the review and the novel itself, eitherwrite your own or write a response to one ofthem. You might want to read this article onwriting a great book review before you ebook-review/467626. Finally, send your response to your teacher sothey can create a database of reviews forrecommendations.

Wider Reading and Preparation for A-Level Task 3Context is KeyContext has an equal weighting to language and structural analysis at A Level soa general understanding of the literary era texts sit in is vital. Literatureconstantly evolves as new movements emerge to speak to the concerns ofdifferent groups of people and historical periods.Here are some of the major movements and eras of English Literature: Medieval Renaissance (Shakespeare) Enlightenment Restoration and 18th Century Romantics and Victorian Realism Existentialism Naturalism 20th Century How many do you recognise? (Some of these overlap) Do you know what they represent? Choose one to research and produce a A3 mind map ofyour key findingsThe British Library’s Discovering Literature Website is a real treasure trove for anyone interested in Literature. Itincludes hundreds of articles on texts from Chaucer to 21st century novels such as Andrea Levey’s Small Island, plusimages of many of the fascinating items in the British Library Collection.The Dicsovering Library website is divided into the following periods: Medieval https://www.bl.uk/medieval-literature Shakespeare https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare(Including: Macbeth, Much Ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet, TwelfthNight and The Tempest) Restoration and 18th Century re Romantics and Victorian ng: Wordsworth, Blake, Coleridge, Jane Eyre, Frankenstein,Pride and Prejudice, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Oliver Twist, AChristmas Carol, Hard Times, Christina Rossetti) 20th Century g: An Inspector Calls, Animal Farm, the poetry of Wilfred Owen, Nineteen Eighty-Four)The first thing you could do is simply spend an hour or so exploring the different sections of the website, allowingyourself to follow whatever paths interest you. (It might be worth having a Word document open so that you can copyand paste titles and web addresses of anything you might want to return to later. But on this first visit, you could just bean interested browser!)Over the next few weeks you could complete the British Library Critical Treasure Trail Read an article that’s caught your attention and select one key point – a bit of treasure – from it. Use the linke on the right-hand side of the web page to follow a critical trail through the site. Read two more articles, collecting bits of treasure as you go. Share your treasure as quotations on a platform recommended and validated by your school. You could also record a short audio guide to the trail you followed and the treasure you found.

Wider Reading and Preparation for A-Level Task 4Banned Books!Many texts now on the GCSE, A Level and manyuniversity curriculums were once ‘banned’It might not surprise you that books, due to theirsexual, political or religious nature were oncebanned but it might shock you that books still -john-green-jillian-tamaki-comics-booksRead the article above.In a world where we have so many outlets to rant and rave and in a country wherewe have freedom of the press how do we not know so much? Knowledge is powerand you can’t complain about what you don’t know about. So read a ‘banned’ bookfrom the lists above and write up what you think of the text including why it wasbanned.Consider the below when you are compiling your response:A book can be banned for one or more of the following reasons: racial issues, encouragement of “damaging” lifestyles,blasphemous dialog, sexual situations or dialog, violence or negativity, presence of witchcraft, religious affiliations(unpopular religions), political bias, or age inappropriateness.1. When did books start getting banned?2. Do you agree that some books should be censored/banned?3. What book were you most surprised was banned and why?4. Does having a book banned make you more curious to read it?5. Why have political regimes burnt books?Why not try a quiz to test your new found books.quiz

Wider Reading and Preparation for A-Level Task 5Transform a TextPlaying and messing about with a text or transforming it in two or threedifferent ways is a really effective and fun way to investigate and clarify foryourself what is distinctive about the original. It’s something both creativewriters and critics do. Read Andrew McCallum’s emagazine article on recreative andtransformative writing. (See next page.)Now experiment with one or more of the activities suggestedhere:Experimenting with the form and layout of a poem Choose a poem you like. This could be one you have studied at school or one you find online. Some greatwebsites to browse to find a poem are suggested below.Online poetry libraries Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/The Saturday daypoemNational Poetry linepoetry/poemsPoem Hunter https://www.poemhunter.com/Poetry by Heart y/Scottish Poetry Library https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/Library of Congress Archive ://poets.org/ https://poets.org/a) Copy and paste the poem into a Word document or type it up. Make a copy of it and arrange it so it looks likeone continuous piece of prose.b) Now experiment with different ways of making the lines break. What different effects can you create? Tryreading your different versions out loud. Do your line breaks make you read it differently?c) If you are enjoying this, you might be interested in reading this Poetry Foundation 70144/learning-the-poetic-lineA transformation from prose to dramaa)Take a short extract from a novel you know well (for example, AChristmas Carol or Jekyll and Hyde) and experiment with turning it into a piece ofdrama.b)What changes do you have to make?c)Is anything lost in the transformation? Is anything gained?A visual experiment with fontsIn 2012 graphic artists were invited to play with the first page of Great Expectations usingtheir choice of font and layout to reveal the meaning they see in the opening to thenovel. Each designer was also asked to explain their thinking behind theirtransformation. The designs were collected in the book Page One.a) Look at some examples 1-great-expectationsb) Can you do the same for a text you know well?c) Present the original and transformed text side by side, along with a shortreflection on what you have discovered. Share it with your classmates via the platform Microsoft Teams.

What is Re-creative Writing?Andrew McCallum explains the possibilities opened up by the re-creative process andencourages you to get your creative juices flowing.Experimental French writer Raymond Queneau one morning observed a man on a bus accusing another of jostling him.He described the incident in just over 100 words, under the heading 'Notation'. He then re-wrote the same event fromdifferent narrative perspectives in 98 different ways, using titles such as 'Blurb', 'Onomatopoeia', 'Rainbow','Exclamations' and 'Botanical', gathered together in a book called Exercises in Style. Each is an example of re-creativewriting. An original work is made afresh; the new version brings additional meaning to its source, which, in turn, throwslight on narrative choices made in the re-creation.Re-creative writing in schools generally asks that you turn a published piece of work into something else (hence it isoften called 'transformative' writing). For example, you might re-write a passage from a novel in a different genre, turn itfrom prose into poetry, set it in a different historical period, or re-imagine it from the perspective of a minor character.Such strategies can be a lot of fun, but they have also gained sufficient credibility to be an assessed part of some A LevelLiterature specifications. The examiners are effectively stating that you can demonstrate critical reading through recreative writing.How is Re-creative Writing Different to Writing Essays?Re-creativity combines elements of the critical and the creative, offering a refreshing alternative to essay writing, thetraditional mode of responding to literature. For where essays analyse texts in abstract ways that place a clearseparation between the roles of writers (creators) and readers (critics), re-creativity allows readers to demonstrateunderstanding using the same resources as writers. They act as both creator and critic. This is not to suggest thatEnglish courses do away with essays. They demand rigour, enabling you to represent ideas in intellectually convincingways. However, re-creative writing has challenges all of its own. In acting as an author, you must show understanding ofa text by writing one yourself. Suddenly you are not required so much to analyse literature, as do it.Isn't it Cheating?If you are sceptical about re-creative writing as a critical technique, you might consider how famous authors use it andwhether or not, in fact, all imaginative work is re-creative. For all writing comes from somewhere, be it drawn from awriter's own life or from his or her reading. Indeed, re-creativity might stand as the writing technique supreme in a postmodern world, where supposedly nothing is original and everything a reworking of what has gone before. Not that it is awholly contemporary phenomenon. Shakespeare uses re-creativity as much as anyone. A large number of his playsrework identifiable sources. For example, Macbeth draws on Holinshed's Chronicles, which give an historical account ofan actual Scottish king.Shakespeare's form of re-creativity differs in one significant way to that used by authors today. While you can gainunderstanding of his work by comparing it to his sources, it is unlikely he was self- consciously offering his own versionsas a point of comparison to the originals, which would not necessarily be known to most of his audience. In contrast,modern writers who use re-creativity are aware that many readers will be familiar with their source material. They wantto create something new, but they also want their work to stand as a point of comparison with the original. This bringsnew meaning to both versions. It can be particularly effective when dealing with issues that have been thought about invery different ways in different historical periods. For example, the two novels below both challenge constructions ofrace and ethnicity in texts.Wide Sargasso SeaFirst published in 1966, Jean Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea is a prequel to Charlotte Brontë's much older Jane Eyre, tellingthe story of how the first Mrs Rochester came to be locked up in the attic of her husband's mansion. The 'madwoman inthe attic' is transformed in Rhys's novel into a lively woman with real hopes, fears and desires. Her descent into madnessis then linked to rejection by her husband, which comes in turn from his rejection of her Creole heritage. Rhys forcesyou to question how Brontë's original can fail to explore the character of the woman in the attic. Does her backgroundmake her of little value to the culture of her time? And how does this affect the way we read Jane Eyre today?

On BeautyZadie Smith's 2005 novel, On Beauty, is based loosely on E.M. Forster's 1910 novel Howards End. However, Smith'swork does not so much critique the original as draw on it for inspiration. It offers a modern take on Forster'sexploration of what happens when two families with different values become interlinked. Smith sets her book in theUnited States rather than England; her characters, like Forster's, are middle-class, but black while his are white. There isnothingunusual about a black family in the States being middle class. However, it is relatively unusual for one to be portrayed inan award-winning novel. The book challenges readers to view the characters in a similar way to Forster's; in otherwords, according to their behaviour rather than ethnicity. Her critique, then, is of the way we read rather than ofHowards End.Achieving a Re-creative Frame of MindBooks expose readers to new worlds. Re-creativity offers the opportunity to transform those worlds. You explore anoriginal text, identify a gap or a point of interest, and create it afresh. In doing so you enter into the original world onterms of your own making. What you re-create acts in a way as a critical comment. But it can also do much more. It hasthe potential to bring you closer to what you read, turning it into something similar to actual lived experience. Thinkabout the examples from Rhys and Smith. Both take something they have read and transform it to fit in with their ownunderstanding of life. Re-creative writing thus offers a connection to original texts unavailable in essay writing. One wayto experience this explicitly is to embed your own persona within a re-creative text. For example, you might write adialogue in which you talk to a novel's central character about his or her behaviour and ideas. You will find yourselfmaking critical comments that would never occur in a formal essay, no matter how much your teacher encourages a'personal response'.Experimental Re-creativityRe-creative writing does not have to be personal. Raymond Queneau's Exercises in Style, with which this article starts,might usefully be termed 'experimental re-creativity' for the way it explores multiple narrative possibilities. Queneau cofounded a school of literature called Oulipo, which stands for Ouvroir de Litterature Potentielle, roughly translated as'workshop of potential literature'. Its members seek to demonstrate that language can be endlessly creative even withinconstraints. For example, Queneau used a mathematical formula to write one hundred billion poems - I'll let you searchthe internet to find out how. Another co-founder, Georges Perec, wrote a novel called La Disparation without using theletter 'e'. If this sounds fantastical enough, consider the process by which Gilbert Adair translated it into English, alsowithout using an 'e'. His version, A Void, is 50 pages longer than the original!The seemingly straightforward task of writing a passage without the letter 'e' is a good introduction to re-creativewriting. It de-familiarises the writing process, forcing you to grapple with vocabulary and syntax. It highlights how allwriting involves choice and that meaning flows from the specific ones made. Here is my own e-free re-write of theopening to Great Expectations, alongside the original. I recommend you try this with one of your own favourite booksto get your re-creative juices flowing.My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both namesnothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.My dad's last was Pirrip, and my first was Philip, but my infant talk could only say Pip. So I was Pip, and am Pip to thisday.I don't think I'm a contender to be the modern-day Dickens. But my experiment drew my attention to how the rhythmof the original is interrupted by the harshness of 'Pirrip', 'Philip' and (three times) 'Pip'. Dickens leaves you in no doubtabout who is the lead character in this book. I guess my version does a similar thing, but with shorter sentences there isno rhythm to break up and so any effect is lost. I am, though, on my way to experiencing how Dickens himself wrote.The next step is to move on to re-creativity proper by, for example, attempting an opening to a novel in the style ofGreat Expectations using a character of my own.Article Written By: Andrew McCallum is course leader for the PGCE in Secondary English with Media and Drama at LondonMetropolitan University and author of Creativity and Learning in Secondary English (2012).This article first appeared in emagazine 57, September 2012.

Welcome to EDUQAS A-Level English Literature! The study of English Literature at A Level is challenging, stimulating and creative. The course develops a number of transferable skills by encouragi