Transcription

TopicHistorySubtopicAncient HistoryArchaeologyAn Introduction to the World’sGreatest SitesCourse GuidebookDr. Eric H. ClineThe George Washington University

PUBLISHED BY:THE GREAT COURSESCorporate Headquarters4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299Phone: 1-800-832-2412Fax: 703-378-3819www.thegreatcourses.comCopyright The Teaching Company, 2016Printed in the United States of AmericaThis book is in copyright. All rights reserved.Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above,no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored inor introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted,in any form, or by any means(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise),without the prior written permission ofThe Teaching Company.

iEric H. Cline, Ph.D.Professor of Classics and AnthropologyDirector of The George WashingtonUniversity Capitol Archaeological InstituteThe George Washington UniversityDr. Eric H. Cline is a Professor of Classicsand Anthropology, the former Chair ofthe Department of Classical and NearEastern Languages and Civilizations, and thecurrent Director of The George Washington University (GWU) CapitolArchaeological Institute. He is also a National Geographic Explorer, aFulbright Scholar, a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) PublicScholar, and an award-winning teacher and author. He holds a Ph.D. inAncient History from the University of Pennsylvania, an M.A. in NearEastern Languages and Literatures from Yale University, and a B.A. inClassical Archaeology modified by Anthropology from Dartmouth College.In 2015, he was awarded an honorary doctoral degree (honoris causa) fromMuhlenberg College.An archaeologist and ancient historian by training, Dr. Cline’s primary fieldsof study are biblical archaeology, the military history of the Mediterraneanworld from antiquity to the present, and the international connections amongGreece, Egypt, and the Near East during the Late Bronze Age (1700–1100 B.C.E.). He is an experienced and active field archaeologist, withmore than 30 seasons of excavation and survey to his credit in Israel, Egypt,Jordan, Cyprus, Greece, Crete, and the United States. Dr. Cline is currentlycodirector of the renewed series of archaeological excavations at the site ofTel Kabri in Israel, which began in 2005. The project is run by the Universityof Haifa (with Assaf Yasur-Landau) and GWU. Dr. Cline was also a memberof the Megiddo Expedition in Israel, excavating at biblical Armageddon for10 seasons over a 20-year period, from 1994 to 2014. In 2015, Dr. Cline wasnamed a member of the inaugural class of NEH Public Scholars, receivingthe award for his next book project.

iiArchaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest SitesAt GWU, Dr. Cline has won the Oscar and Shoshana Trachtenberg Prizefor Teaching Excellence and the Oscar and Shoshana Trachtenberg Prize forFaculty Scholarship; he is the first faculty member at GWU to have won bothawards. He also won the national Excellence in Undergraduate TeachingAward from the Archaeological Institute of America. Dr. Cline teaches awide variety of courses at GWU, including Introduction to Archaeology,History of Ancient Greece, History of Egypt and the Ancient Near East, andHistory of Ancient Israel, as well as various smaller honors and freshmenseminars. He has also served as the advisor to undergraduate archaeologymajors at GWU since 2001.Dr. Cline’s most recent book, 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed,received the 2014 Award for the Best Popular Book from the AmericanSchools of Oriental Research and was considered for the 2014 PulitzerPrize. Three of his previous books have won the Biblical ArchaeologySociety’s award for Best Popular Book on Archaeology. His books havealso been featured as a main selection of the Natural Science Book Club, amain selection of the Discovery Channel Book Club, a USA TODAY “Booksfor Your Brain” selection, and a selection of the Association of AmericanUniversity Presses for Public and Secondary School Libraries.A prolific researcher and author with 16 books and more than 100 articlesand book reviews to his credit, Dr. Cline is perhaps best known for suchbooks as The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley fromthe Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age; Jerusalem Besieged: From AncientCanaan to Modern Israel; From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries ofthe Bible; Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction; and The TrojanWar: A Very Short Introduction. His books have been translated or arebeing translated into 14 languages. His research has been featured in TheWashington Post, The New York Times, U.S. News & World Report, USATODAY, National Geographic News, CNN, the London Telegraph, theLondon Mirror, the Associated Press, and elsewhere, His books have beenreviewed in The Times Literary Supplement, Times Higher Education, TheJerusalem Post, the Cincinnati Enquirer, the History News Network, JewishBook World, and many professional journals.

iiiDr. Cline has also appeared in more than 20 television programs anddocumentaries, including those on ABC, the BBC, the National GeographicChannel, HISTORY, and the Discovery Channel. Dr. Cline has beeninterviewed by syndicated national and international television and radiohosts on such shows as ABC’s Good Morning America, Fox News Channel’sAmerica’s Newsroom, the BBC World Service’s The World Today, NPR’sPublic Interest, and The Michael Dresser Show. In addition, he has presentedmore than 300 scholarly and public lectures on his work to a wide variety ofaudiences both nationally and internationally, including at the SmithsonianInstitution in Washington DC, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in NewYork, and the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles.

Table of ContentsINTRODUCTIONProfessor Biography.iCourse Scope.1LECTURE GUIDESLECTURE 1The Origins of Modern Archaeology 3LECTURE 2Excavating Pompeii and Herculaneum 10LECTURE 3Schliemann and His Successors at Troy 17LECTURE 4Early Archaeology in Mesopotamia 24LECTURE 5How Do Archaeologists Know Where to Dig? 32LECTURE 6Prehistoric Archaeology 39LECTURE 7Göbekli Tepe, Çatalhöyük, and Jericho 46LECTURE 8Pyramids, Mummies, and Hieroglyphics 53LECTURE 9King Tut’s Tomb 60LECTURE 10How Do You Excavate at a Site? 67

Table of ContentsvLECTURE 11Discovering Mycenae and Knossos 74LECTURE 12Santorini, Akrotiri, and the Atlantis Myth 82LECTURE 13The Uluburun Shipwreck 90LECTURE 14The Dead Sea Scrolls 97LECTURE 15The Myth of Masada? 104LECTURE 16Megiddo: Excavating Armageddon 111LECTURE 17The Canaanite Palace at Tel Kabri 118LECTURE 18Petra, Palmyra, and Ebla 124LECTURE 19How Are Artifacts Dated and Preserved? 131LECTURE 20The Terracotta Army, Sutton Hoo, and Ötzi 138LECTURE 21Discovering the Maya 146LECTURE 22The Nazca Lines, Sipán, and Machu Picchu 154LECTURE 23Archaeology in North America 162LECTURE 24From the Aztecs to Future Archaeology 170

viArchaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest SitesSUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALBibliography 177Image Credits 191

Archaeology: An Introduction to theWorld’s Greatest SitesScope:What, exactly, is it that archaeologists do? Although tremendous numbers ofpeople are fascinated by the idea of archaeology, many have little idea whatis involved. Indeed, many people picture an archaeological excavation as anIndiana Jones movie.This course is meant to set the record straight. It is an introduction toarchaeology for the general public that provides answers to the questionsarchaeologists are asked most frequently: How do archaeologists findancient sites? What happens during an actual excavation? How do we knowhow old something is?In answering these questions, this course provides the inside story of whatit is that archaeologists actually do and how they do it. We will learn howwhat began as a haphazard search for famous sites of ancient history evolvedinto a highly organized, professional, and systematic study of the peoplesand cultures of the past—progressing from the first crude excavations atHerculaneum to the high-tech methods being used at Teotihuacan today.We’ll also get firsthand insight into how cutting-edge technology has foreverchanged the field.In addition, we will discuss some of the most famous archaeologicaldiscoveries of all time, including the tomb of King Tut, the Uluburunshipwreck, the Nazca Lines, and the amazing terracotta warriors.These discoveries are arranged thematically, both chronologically andgeographically. We’ll travel the world—from Ur in Mesopotamia to China’sShanxi Province, from Masada in Israel to the ancient town of Akrotiriin Greece, from Sutton Hoo in England, to Machu Picchu in Peru. We’ll

2Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sitesalso include forays into Spain and France, Italy and North America, Africa,Mexico, and Turkey.Whether you’re new to the subject or you’re an archaeology enthusiast, thiscourse will provide an unparalleled glimpse into a critical source of historicalknowledge.

LectureX1The Origins of Modern ArchaeologyThe field of archaeology began as a haphazard search for ancient statuesand famous sites of history but has evolved into a highly organized,professional, and systematic study of the peoples and cultures of the past.In this course, we’ll explore some of the most famous archaeological discoveriesof all time, and we’ll look at how cutting-edge technology has changed the field.By the end of the course, you’ll be an expert in excavation, and you’ll possessa deeper appreciation for why saving the past matters. Archaeology not onlyteaches us about the past, but it also connects us to a broader range of humanexperience and enriches our understanding of our present and our future.Ancient Archaeologists The first archaeologist we know of lived more than 2,500 years ago.He was the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus, who ruled in ancientIraq and Syria during the middle of the 6th century B.C. Nabonidusis known to have excavated ancient buildings and even set up amuseum so that he could display the objects he found. Nabonidus wasn’t the only person in antiquity who was interestedin what had come before him. The Greek writer Hesiod, who wrotea poem called Works and Days in about 700 B.C., before the timeof Nabonidus, referred to the earlier periods in Greece as the Ageof Gold, the Age of Silver, and so on. Hesiod lived during a periodof regeneration after centuries of the world’s first Dark Age, and hecalled his own time the Age of Iron. Archaeologists still call thatperiod the Iron Age, thanks in part to Hesiod.Early Modern Archaeologists In terms of the modern world, one of the first people to try to lookback at the stretch of human history was Archbishop James Ussher.In the 1600s, he went through the Bible and added up the variousdates for people mentioned there, such as Noah, Joshua, Abraham,and so on, and came up with the idea that the world had been createdabout 6,000 years ago—specifically, on October 23, 4004 B.C.

4Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites The origins of modern archaeology probably go back to the early1700s, when people first started exploring the ancient Italian ruinsthat had been buried by an explosion of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Credit here usually goes to a man named Emmanuel Mauricede Lorraine, who was the prince (and, later, duke) of Elbeuf,in Austria. He was living in Italy near Naples at the timeand underwrote the first efforts to tunnel into the ground atHerculaneum, a town near Pompeii. His men happened to dig right into the ancient Roman theaterat Herculaneum and were able to extract a number of marblestatues. Most of these were used to decorate EmmanuelMaurice’s estate; others were distributed elsewhere inEurope, including to some museums. Proper excavations atHerculaneum and Pompeii began a few decades later. Interestingly, Thomas Jefferson also did a bit of archaeology in thelate 1700s. In fact, some think that what he did should count as thefirst real archaeological excavations conducted in the New World. In about 1784, he excavated a Native American burial moundon his property in Virginia. He was able to tell that there weredifferent layers in the mound and that the bodies in it had beenburied at different times. In this, Jefferson was far ahead of his time. Today, the ideaof separate layers is known as stratigraphy, but it wouldn’tbecome an established part of archaeology until the time of SirWilliam Matthew Flinders Petrie, who excavated in Egypt andPalestine a century later.Archaeology in the 19th Century By the mid-1800s, serious excavations were underway at a numberof ancient sites in the Near East, underwritten by such institutionsas the British Museum and the Louvre and conducted by Sir AustenHenry Layard, Paul Émile Botta, and others. They excavatedin what is now Iraq at such places as Nineveh and Nimrud andshipped magnificent pieces back to the museums for display. These

Lecture 1—The Origins of Modern Archaeology5pieces include the colossal winged bull and lion statues from thepalaces of Sargon II and Ashurnasirpal II that are currently ondisplay at the British Museum. Other 19th-century archaeologists, such as John Lloyd Stephens,went exploring in the New World. Stephens, along with a Britishartist named Frederick Catherwood, traveled in the Yucatan, inmodern-day Mexico. They published beautiful books about theirtravels in the 1840s, in which they reported the discovery ofpreviously unknown Maya sites. The fledgling field of archaeology, as it began to grow and solidify,borrowed heavily from other disciplines, especially geology. JamesHutton and Charles Lyell, considered to be among the fathers ofgeology, had suggested theories concerning the stratification ofrocks. They believed that the lower down in the earth one went, theearlier the rocks would date; that is, the earlier rocks had beenlaid down in the strata first, with later levels coming in on topof them. This is similar to what Thomas Jefferson had concluded; it’salso a premise that would form the basis of Petrie’s excavations. Another advance came from a Danish museum curator named C.J. Thomsen, who began cataloguing the objects in the NationalMuseum of Denmark in the 1830s. His results were published inan English edition just before 1850. Thomsen split the museum’scollections of antiquities into three periods: the Stone Age, theBronze Age, and the Iron Age. This system—known as the three-age system—was soonadopted throughout Europe and remains in use to this day,though it now has a number of subdivisions. For instance, theStone Age is divided into the Paleolithic, that is, the Old StoneAge; the Mesolithic, which is the Middle Stone Age; and theNeolithic, the New Stone Age.

6Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites The Bronze Age is frequently subdivided even further, accordingto location. The timing of the Bronze Age varies depending onwhere you are in the world; for example, the Bronze Age inChina took place at a different time than either the Bronze Agein Europe or the Bronze Age in the ancient Near East. By the 1860s and 1870s, Heinrich Schliemann was searching for thelegendary city of Troy. Going against the scholars of the day, mostof whom didn’t think the Trojan War had taken place, Schliemannbegan excavating at the site of Hisarlik in northwest Turkey andsoon announced to the world that he had found Troy. Later, he alsoannounced that he had uncovered the ruins of Mycenae, home toAgamemnon, who led the Greek army in its assault on Troy. At around the same time, various people were working to decipherancient languages. Probably the most famous person in this fieldis Jean-François Champollion, the brilliant French scholar who iscredited with deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics in 1823. Another language scholar was Sir Henry Rawlinson, whohelped to translate the cuneiform script in Mesopotamia in the1850s. Cuneiform is a wedge-shaped writing system that wasused to write Akkadian, Babylonian, Hittite, Old Persian, andother languages in the ancient Near East. Rawlinson cracked the cuneiform system by translating atrilingual inscription written in Old Persian, Elamite, andBabylonian. Darius the Great of Persia, in about 519 B.C., hadcarved the inscription into a cliff face at the site of Behistun inwhat is now Iran.Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie By the end of the 19th century and into the 20th, some of the greatearly archaeologists began to appear on the scene. One of the mostimportant of these was Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie. Petrie first dug in Egypt, where he trained a group of workmenfrom a village near modern-day Luxor. To this day, the descendants

Lecture 1—The Origins of Modern Archaeology7of those men, known as guftis, still provide much of the skilledlabor for archaeological excavations in Egypt. Each gufti doesthe same task that his family has always done; some are pickmen,some are trowelmen, and so on. Petrie also dug in what is now modern Israel but was Palestine in hisday. Here, he was responsible for the introduction or popularizationof a number of concepts that are taken for granted in archaeologytoday. For example, he applied the concept of stratigraphy, adoptedfrom geology, and argued that earlier things are usually found lowerdown than more recent things, especially in the man-made moundsknown as tells that can be seen throughout the Middle East. Of course, Petrie was right; tells are actually made up ofone ancient city on top of another, built up over centuries ormillennia, and the earliest city is always at the bottom.The tell (ancient mound) at Megiddo, which is the site of biblicalArmageddon, is made up of 20 different cities in layers.

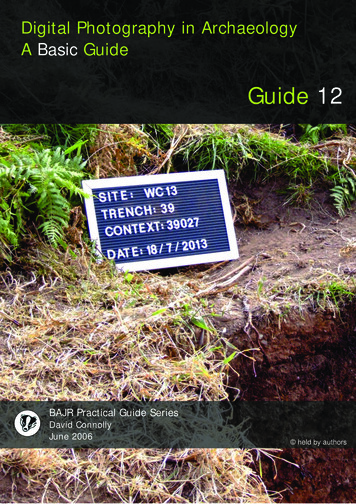

8Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites For example, at Megiddo, the 70-foot-tall mound has no fewerthan 20 different cities hidden within it, with the first one, at thebottom, dating back to at least 3000 B.C. and the most recentone, at the top, dating to about 300 B.C. Petrie is also one of the people responsible for realizing that brokenpieces of pottery removed while digging can be used to help datedifferent levels of a mound. Because styles of pottery go in and outof fashion, certain types can be correlated, especially in conjunctionwith radiocarbon dating, with fairly specific dates and periods.Petrie also realized that if the same type of pottery is found at twodifferent sites, the levels in which they are found at each site areprobably equivalent in time. This has proven to be an extremelyuseful point.The idea of separate layers representing successively earlierperiods on an archaeological site is known as stratigraphy.

Lecture 1—The Origins of Modern Archaeology9Sir Mortimer Wheeler and Dame Kathleen Kenyon Sir Mortimer Wheeler excavated at Maiden Castle in England andHarappa in India. At both sites, he excavated in 5-meter squares,with a 1-meter-wide balk in between the squares, on whichexcavators could walk, push wheelbarrows, and so on. Wheeler’sstudent Kathleen Kenyon, who is probably best known for diggingat Jericho and Jerusalem, brought this method with her when shebegan excavating in what was then Palestine in the 1930s. It is nowknown as the Wheeler-Kenyon or Kenyon-Wheeler method. This method allows the archaeologist to keep control of thestratigraphy, by looking at the interior sides of each square to seewhat has already been dug through and to get a visual idea of thehistory of the area. At the end of each season, most archaeological teams in the NearEast draw and photograph each of these sections so that they canpublish a record of it for others to see and discuss. The reason for thisstep is that archaeologists destroy the very things they are studyingas they dig; thus, it’s important to record every detail of the process.Suggested ReadingBahn, 100 Great Archaeological Discoveries.Fagan, ed., The Great Archaeologists.Fagan and Durrani, In the Beginning.Questions to Consider1.Might there be a better way to divide and subdivide the periods ofantiquity rather than the three-age system that Thomsen created?2.What do you think of the excavation techniques introduced by Petrie,Wheeler, and Kenyon? Can they be improved upon?

LectureX2Excavating Pompeii and HerculaneumMount Vesuvius is located near the modern city of Naples, Italy. Itis the only active volcano on the mainland of Europe today; aswe know, it erupted on August 24, 79 A.D., killing at least 2,000people in Pompeii, plus others in nearby towns, such as Herculaneum. Atthe time, Pompeii was a wealthy Roman town; in fact, it may have beensomething of a resort city—used as a getaway for wealthy members ofsociety wishing to escape from Rome. Herculaneum, too, was a wealthycity, perhaps even more so than Pompeii. In this lecture, we’ll look at thedestruction and later excavation of these sites.The Eruption We actually have an eyewitness description of the eruption of MountVesuvius, contained in two letters written by Pliny the Younger andsent to the Roman historian Tacitus. Pliny was 17 years old at thetime and had been staying with his uncle, Pliny the Elder. The elder Pliny was in charge of the Roman fleet, which was stationedacross the Bay of Naples from Vesuvius, at Misenum. During theeruption, the older Pliny attempted to sail to the rescue and save someof the fleeing survivors, but he died while doing so. The youngerPliny remained at Misenum, watching the eruption. His letters are fullof details, based both on what he observed and what was later told tohim by the men who had been with his uncle on the ships. Pliny’s second letter, in particular, brings the story of the eruptionto life:Behind us were frightening dark clouds, rent by lightning twistedand hurled, opening to reveal huge figures of flame. I lookback: a dense cloud looms behind us, following us like a floodpoured across the land. [Then] a darkness came that was notlike a moonless or cloudy night, but more like the black of closedand unlighted rooms. You could hear women lamenting, childrencrying, men shouting. Many raised their hands to the gods,

Lecture 2—Excavating Pompeii and Herculaneum 11and even more believed that there were no gods any longer andthat this was one last unending night for the world. As we know, for centuries afterward, Pompeii, Herculaneum, andother towns lay buried beneath several meters of ash and rock.Pompeii was the first of these towns to be discovered (in 1594),but Herculaneum was the first to be excavated. In the early 1700s,the duke of Elbeuf ordered his men to tunnel into the ground atHerculaneum after he bought the site specifically because ancientpieces of marble had been recovered from the area. The workmenhappened to dig into the Roman theater and extracted a number ofancient marble statues. The earliest excavations at Pompeii were unprofessional, to say theleast, frequently involving simply digging tunnels until somethingancient was unearthed. Rather than archaeology, it was more likelooting, but it was the first known excavation done in the modern era.However, proper excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii began afew decades later and have essentially been ongoing ever since.Herculaneum In addition to being hit with ash and pumice, Herculaneum seemsto have been the victim of a 30-foot mudflow, known as a laharin geological terms. This filled up the buildings and completelyburied the city. Being buried in such a manner essentially preservedHerculaneum, freezing it just as it had been on that August morningin 79 A.D. Archaeologists working in 1981 discovered that Herculaneum hadsuffered yet another horror during the eruption of Vesuvius. Until that point, relatively few human remains had been found,and it had long been assumed that most people had successfullyfled or been evacuated. However, in excavations that year andagain in the 1990s, archaeologists found the bodies of at least300 people who had taken refuge in what seem to be boathouses on the shore.

12Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites The people were probably waiting to be picked up by ships fromthe Roman fleet; however, a blast of heat, estimated at 1000 F,swept through the area. According to forensic anthropologists,the people were probably killed instantaneously. Only theirskeletons remained; their skin and internal organs weredestroyed by the heat and the hot ash that covered the bodiesalmost immediately. The same intense heat and ash also destroyed other organic materialin the town, including private libraries and documents written onscrolls. These were turned into what are described as “cylinders ofcarbonized plant material.” Up to 300 of these scrolls were foundintact during the earliest excavations at Herculaneum (in 1752) ina villa that probably belonged to the family of the father-in-law ofJulius Caesar. In looking at photographs of these scrolls, it’s difficult to seehow they could possibly be unrolled or read in any way. Butrecent investigators have discovered a technique for makingout letters written on the scrolls without unrolling them. The technique involves using X-rays in a “laserlike beam,”which allows researchers to detect “the contrast betweenthe carbonized papyrus and the ink.” It is not yetknown whether the technique will work well enough to allowthe carbonized scrolls to be read in their entirety, but it is anexciting development in archaeology.Pompeii Excavations at Pompeii first began around 1750. Here, the ashand pumice that covered the town mixed with rain and eventuallyhardened into the consistency of cement, encasing hundreds ofbodies. Over time, the flesh and inner organs of each body decayedslowly, forming hollow cavities in the ash in the shape of the bodythat had once been buried there. In 1863, Giuseppe Fiorelli, the Italian archaeologist in charge ofexcavating Pompeii, directed his team to pour plaster into these

Lecture 2—Excavating Pompeii and Herculaneum 13Early excavators in Pompeii found a town frozen intime from 79 A.D.; bread was still on the tables, a dogremained chained up outside, and bodies were in thestreets, some still clutching jewelry and other objects.cavities, yielding an exact cast of what had originally formedthe cavity. In this way, Fiorelli’s team recovered the remainsof hundreds of bodies, as well other organic materials, suchas wooden furniture and loaves of bread. They also recoverednonorganic objects, ranging from jewelry to silverware to jugsmade of precious metals. The houses in Pompeii were quite elegant, and just as inHerculaneum, they are extremely well preserved. One called theHouse of the Faun features a bronze statue of a faun, the satyr-likecreature that is usually depicted playing the double-pipe. This samehouse also has the famous Alexander Mosaic, which uses hundredsof thousands of small stone tesserae to depict Alexander the Greatfighting the Persian king Darius III.

14Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites The eruption of Vesuvius also buried the gardens that belongedto some of the houses in Pompeii. In 1961, the archaeologistWilhelmina Jashemski excavated an open area in Pompeii andfound the remains of root cavities from the plants that had oncebeen there. In fact, she was able to figure out the planting pattern inwhat was once a vineyard. Elsewhere in Pompeii, archaeologists have uncovered the remainsof bath houses, tanneries, shops, and other dwellings that one wouldexpect to find in a city from the period. Some of the most recentfindings come from the excavations of Steven Ellis, a professor atthe University of Cincinnati. In 2014, after digging in an area by thePorta Stabia, one of the main gates into the city, Ellis announcedthat he had found 10 separate building plots with 20 shopfronts fromwhich food and drink were sold or served. Such an arrangementseems typical in Pompeii, where even the private houses frequentlyhad shops installed on the street. Even more interesting, perhaps, were the drains, latrines, andcesspits that Ellis and his team excavated. In these, they foundthe remains of “grains, fruits, nuts, olives, lentils, local fish, andchicken eggs, as well as minimal cuts of more expensive meat andsalted fish from Spain.” In another drain, they found the remains of“shellfish, sea urchin, a

History of Ancient Greece, History of Egypt and the Ancient Near East, and History of Ancient Israel, as well as various smaller honors and freshmen seminars. He has also served as the advisor to undergraduate archaeology majors at GWU since 2001. Dr. Cline’s most recent b