Transcription

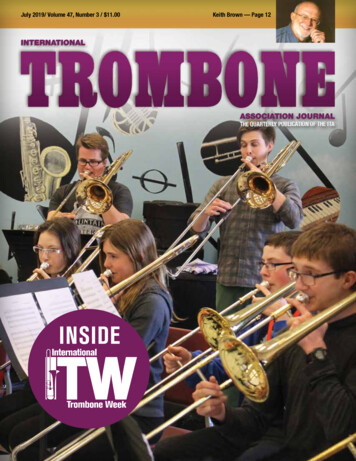

July 2019/ Volume 47, Number 3 / 11.00Keith Brown — Page 12INTERNATIONALASSOCIATION JOURNALTHE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE ITAINSIDE

INTERNATIONALTROMBONEASSOCIATION JOURNALThe Quarterly Publication of the ITAVolume 47, Number 3 / July 2019News — Page 6The International Trombone Association is Dedicated to the ArtisticAdvancement of Trombone Teaching, Performance, and Literature.ContentsFeaturesITA JOURNAL STAFFManaging EditorDiane Drexler3834 Margaret Street, Madison, WI 53714 USA / diane@trombone.netAssociate EditorJazz – Antonio GarciaMusic Department, Virginia Commonwealth University, 922 Park Avenue,P.O. Box 842004, Richmond, VA 23264-2004 USA / ajgarcia@vcu.eduAssistant EditorsKeith Brown: Renaissance Manby Douglas Yeo.12Beethoven’s Funeral Musicby Andrew Glendening.36ITW Retrospectiveby Colleen Wheeler . 38Nikolai Sergeievich Fedoseyev and the Piano Reductionfor Rimsky-Korsakov’s Concerto for Tromboneby Timothy Hutchens.50News Coordinator - Dr. Taylor Hughey950 S Flower St Apt 213, Los Angeles, CA 90015news@trombone.net / 865-414-6816DepartmentsOrchestral Sectional – Weston Sprottweston.sprott@gmail.comPresident’s Column - Ben van Dijk. 5Program & Literature Announcements – Karl HinterbichlerMusic Dept., University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 USAkhtbn@unm.edu / fax 505-256-7006Announcements. 2General News - Dr. Taylor Hughey. 6Nuggets of Wisdom - M. Dee Stewart and Brad Edwards. 11Pedagogy Corner - Joshua Bynum. 30Literature Reviews – Mike HallOld Dominion University – 2123 Diehn Center Center for the Performing Arts4810 Elkhorn Avenue, Norfolk, VA 23529 USAjhall@odu.edu / fax 757-683-5056Literature - Karl Hinterbichler. 56Audio/Video Reviews – Micah EverettDepartment of Music, University of Mississippi, PO Box 1848,University, MS 38677-1848 USA / micah@trombone.netAdvertiser Index. 68Literature Reviews - Mike Hall and David Stern. 58Audio/Video Reviews - Micah Everett. 62Pedagogy Advisory Council – M. Dee Stewart & Brad EdwardsSubmit a Nugget of Wisdom to itaquotes@gmail.comAdvertising Manager and Pedagogy Corner – Josh BynumHodgson School of Music - University of Georgia250 River Road, , Room 457, Athens, GA 30602-7278 USAPhone: 706-542-2723 / journalads@trombone.net / Fax: 706-542-2773The International Trombone is the official publication of the InternationalTrombone Association. I.S.S.N. 0145-3513. The ideas and opinions expressedin this publication are those of the individual writers and are not necessarily thoseof the International Trombone Association. All rights reserved.Cover image – Nathan Gingrich's Slide into Spring celebration from the2016 International Trombone Week. Photo courtesy of Nathan Gingrich.Designed by – Jeff McMillen - jeff@jeffmcmillen.netFor advertising rates or submission guidelines please visit our website:www.trombone.netKeith Brown — Page 12International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net-1-

Keith BrownKeith Brown, c. 1971.-12-International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net

Renaissance Manby Douglas YeoWe all had them, and we had them all. You could not haveonly nine. You had to have all ten. Because when the callcame—and you prayed and prayed and prayed that it wouldcome—you had to have them. If you didn’t have them, youcouldn’t play. And the thing you wanted to do more thananything else was to play.The call usually came on a Friday afternoon. You hadorganized your day so you could be in your dorm room,sitting by the telephone, waiting. Hoping. And when thephone rang—it had that iPhone ring that today is called“old phone” but this really was an old phone, a heavy one,a black one with a dial with holes in it—you smiled. It was happening. And youwere ready.The voice on the other end wasfamiliar. The sentences were short, likethose breathless conversations in lowvoices you heard between gangsters inthose old movies in black and whiteyou used to watch on TV with your dad.Words shot out like machine gun fire.Short. On point. But he wasn’t talking toMugsy or Al Capone. He was talking toyou.“Tonight. Room MA-004. 7 o’clock.Bring your Brown books. Yellow, red,blue, and green. But bring the others, too. You never know.”“Yes,” you said. “You never know.”“Jim and Andrea are coming. Dan, too. Oh, and bringa music stand.”You paused, so as not to sound too eager. Then, “I’ll bethere. I’ll have my Brown books.”Click. The phone went dead. You sat back and lookedat your watch. Your eyes drifted up to the shelf aboveyour desk. There, next to a dog-eared Harvard Dictionaryof Music that you bought used for 8.00 and your pristinecopy of Grout—it was brand new, the most expensivepossession you owned apart from your trombone,purchased with every penny you earned from two Saturdayshifts working at the 7-Eleven because you thought it wouldimpress your girlfriend (she wasn’t impressed)—you sawthem. They were there—all ten of them. And with them,you would play.And so, the ritual began once again; that weeklymeeting of friends, four who played trombone and onewith a tuba. We gathered to play orchestral excerpts. Wesat in Room MA-004, or any room that was available, allin a row, imagining that Solti, or Bernstein, or Ormandy, orOzawa was standing in front of us, conducting. Openingour Brown books, we played our hearts out. We playedour favorites. And then we played them again. And again.We had developed a shorthand, a kind of secret languageto identify them. We didn’t need many words. Prok 5. Oto the end. The Ride. Then we played the solos for eachother. Bolero. Tuba mirum. Hary Janos.And when we were done—when we weredone sitting in chairs where we pretendedwe were our heroes, heroes like Friedmanand Crisafulli and Kleinhammer andJacobs; Herman and Cohen and Ostranderand Novotny; Boyd and Kofsky andAnderson and Bishop; Dodson andStewart and Harper and Torchinsky;Gibson and Barron and Hallberg andSchmitz—we imagined the conductorwould turn to us and, using his baton likeKing Arthur’s sword, Excalibur, touch uson the shoulder, and say, “Rise, you whohave proven yourself worthy. Gather yourBrown books; come and join us.” This was our dream. Thiswas our passion. This was our quest: to attain a positionin a symphony orchestra. And the Brown books helped usget there.Somewhere, someone knows how many copies ofOrchestral Excerpts from the Symphonic Repertoire forTrombone and Tuba Volumes I–X compiled and edited byKeith Brown were sold. I don’t know. I’ve tried to find out,but apparently a number that large has not yet been invented.Thousands? Tens of thousands? A zillion? It doesn’t matter.It is enough to know that from 1964 into the early 2000s,every trombone and tuba player in the United States andmany others around the globe who aspired to an orchestralcareer probably had all ten volumes. And also, his separateexcerpt book of works by Richard Strauss. Keith Brown’sorchestral excerpt books were used by an uncountablenumber of low brass players in an era before the internet,International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net-13-

Keith was my associate in the Philadelphia Orchestra for severalyears. He was a great friend and wonderful colleague. He wasone of the finest trombonists I have ever heard.— Henry Charles Smith IIIPrincipal trombone, Philadelphia Orchestra, 1956–1967Cherry Classics, The One Hundred, and IMSLP. Theywere how we learned the orchestral repertoire. All of it.The standard, the mundane, and the obscure. This is howso many trombonists knew Keith Brown. He was the namebehind the Brown books.And so much more.Our libraries had the Handel Oboe Concerto, the Corelliand Galliard Sonatas, the Speer Sonata for four trombones,Kopprasch and Kreutzer and Mueller and Rode and Blumeand Slama and Stephanovsky and Werner Studies. Theyall bore his name. So did Debussy’s Romance and theSchumann Romances, Marcello’s Sonatas, the Bach CelloSuites and the Baroque master’s viola da gamba Sonatas,Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise, and Vivaldi’s Sonata “Il PastorFido.” And sixty other solos and books of exercises fortrombone as well as chamber works for trombone and brassensembles. Our music cabinets were veritable rainbows,filled with editions by International Music, all with colorfulcovers emblazoned with the name KEITH BROWN.His name was all that many people knew about him; hiseditions never carried his biography. But behind thosewords—KEITH BROWN—was a superb artist/musician/trombonist who had a long career at the highest level.This he did as an orchestral player and soloist, a giftedchamber musician, a conductor, clinician, editor/arranger,and musical ambassador. At the heart of his character, hewas a loving husband, father, grandfather, and uncle. Andto many, he was our teacher, the one who showed us theway. When Keith Brown died on May 9, 2018, at the ageof 84—Parkinson’s disease slowly sapped life from thisvibrant man—the trombone world bowed its head andplaced its collective hat over its heart in honor of one whodid so much for so many.How quickly we forget. Today, most aspiring orchestraltrombonists can name the trombone section members ofdozens of the world’s top orchestras. They are role models,heroes, the ones young players strive to emulate. But asthese titans of the trombone get older and retire, the nextyounger generation often forgets the old heroes as newheroes appear who seem to play ever higher, faster, andlouder. It has always been so. Which is why we do well toremember those players and teachers of years past who, intheir time, were the heroes of an earlier younger generation.My heroes. Your heroes. Our heroes. Keith Brown was oneof them. Here is some of his story.-14-International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.netKeith Brown dressed as a conductor, Columbia ElementarySchool, c. 1939.Early yearsIt was in Colorado Springs, Colorado, at 4:35 a.m. onOctober 21, 1933, where Vernon Keith Brown—the oldestof two sons born to Kenneth Vernon and Audrey LucilleNelson Brown—took his first breath. While his full nameappeared in his school and military records, Keith nevercared for his first name and never used it. He later toldhis son, Bob, that his father had “stuck me with Vernon,”one of those family things that, once you are old enough,you can shed as you stake out your own identity. YoungKeith exhibited an early interest in music. He was the drummajor/conductor with a baton for the Columbia (ColoradoSprings) Elementary School rhythm band when he was fiveyears old, the same year he began piano lessons, and hislips first buzzed through the mouthpiece of a used Kingtrombone his family bought from the high school banddirector in town two years later.By high school, Keith was a gangly teenager andwas involved in band, orchestra, choir, baseball, football(he lettered in both sports), drama club, and the school’syearbook staff. Just before his graduation from ColoradoSprings High School in 1951,1 Keith was informed thathe had been accepted to University of Southern California(USC) in Los Angeles with a 300 scholarship to study

The connection between Marsteller and Brown wasproven in a special way when, in January 1957, Keithgave a recital on which he and Marsteller played severalduets. The recording of the recital has survived, and thecompatibility of sound, technique, and musical conceptis so similar between the two players that it is impossibleto tell who played which part. His senior recital (April 22,1957), included Heiter Villa-Lobos’ Bachianas BrasileirasNo. 5 for soprano and violoncelli, performed by soprano MegSeno accompanied by an ensemble of trombones (includingBrown, Bohannon, Lloyd Ulyate, and Byron Peebles)and tuba (John Thomas “Tommy” Johnson) conducted byMarsteller. While most of his peers anxiously awaited theirentry into the workforce, by the time he graduated, KeithBrown’s illustrious career was already underway.OrchestrasKeith Brown in his USC Marching Trojans uniform, 1951.Photo by Jerome Jansen.trombone with Robert Marsteller. Marsteller—who was inthe midst of his long career as principal trombonist of theLos Angeles Philharmonic and Hollywood Bowl Orchestra(1946–1971)—was, in Keith’s words, “an imposingteacher, quite demanding and yet thoughtful . . . my fatherfigure away from home, tennis coach, academic and lovelife advisor (sometimes effective, many times not)—and,yes, my teacher of music, trombone—and life.”2While at USC, Keith played in the USC Trojan marchingband, symphonic band, and orchestra. He also freelanced;he substituted in the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and was amember of the Pasadena Symphony, the Burbank Symphony(the orchestra’s trombone section also included HoytBohannon, who later became well known for the legendaryweekly gathering of trombonists at “Hoyt’s Garage”) andthe Harbor Symphony (conducted by Marsteller). Keith’seducation at USC was interrupted in 1953 when he wasdrafted into the US Army; he served in the 179th Army Bandat Fort Carson, Colorado, (while concurrently playing firsttrombone with the Colorado Springs Symphony) and afterhis discharge on May 7, 1956, with the rank of TechnicalSargent, he resumed his studies.Two and one-half months before Keith received hisbachelor of music degree from USC—he graduated cumlaude on August 2, 1957—he received a telegram fromthe Indianapolis Symphony, offering him the positionof second trombone with the orchestra. The celebratedcomposer Ingolf Dahl, who had been Keith’s conductingteacher at USC, wrote a letter to support his hiring.Citing Keith’s recent performance of Donal Michalsky’sTrombone Concertino, Dahl effusively wrote, “I can saywithout qualification that it would be a privilege for anyconductor to have such a fine musician in his orchestra.”Dahl also praised Keith’s wife, Leslee Scullin Brown, whohe said was “an unusually gifted double bass player.”3Keith drove a hard bargain. For the orchestra’stwenty-two-week season, he was offered the position at 90 a week; on the strength of Dahl’s letter, Leslee wasoffered a contract for 80. After some negotiations, theysigned contracts for 100 and 85 a week. To generatesome additional income, Keith taught in the IndianapolisPublic Schools for a semester. It was while in Indianapolisthat Keith came to the attention of renowned violinistAlexander Schneider who was assembling the orchestrafor the 1958 Casals Festival in Puerto Rico. The offer toplay principal trombone in the Festival Orchestra for 300a week came by telegram and he accepted the position.He played at the Casals Festival annually for twenty-twoyears.4 After returning home, Keith and Leslee—citingPhiladelphia Orchestra lowbrass section, c. 1961.(left to right) Keith Brown(associate principal),Henry Charles Smith III(principal), Howard Cole(second), Robert Harper(bass), Abe Torchinsky(tuba).International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net-15-

I had the great fortune to knowKeith as a student and later as acolleague. His door was alwaysopen to me; it was exhilaratingto interact with such a giantin the field. His vast and allimportant contributions to ourliterature—solo, study, andorchestral—are unparalleled. Irelished being in the room withthat compendium of knowledge.Many years later it was equallyexciting and rewarding to sharelunches together and be regaledwith stories of a lifetime inmusic. Keith was a treasure, ajewel whose luster will shine forgenerations to come.– Peter EllefsonProfessor of Trombone, Indiana University-16-International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.netthe lack of work in Indianapolis outside the symphony’sseason—informed the Indianapolis Symphony that theywould leave the orchestra to look for playing opportunitiesin New York City.5The year in New York was influential in many ways, notthe least because Keith began work on a master’s degree atManhattan School of Music, joined the New York BrassQuintet, played principal trombone with the Symphony ofthe Air (the successor orchestra to the NBC Symphony),and successfully auditioned for the assistant principaltrombone position with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Thusbegan his three year tenure (1959 to 1962; Keith wasnamed associate principal for the 1961–1962 season) underthe baton of Eugene Ormandy where he played in a sectionalongside Henry Charles Smith III (principal), HowardCole (second), Robert Harper (bass), and Abe Torchinsky(tuba), and played on dozens of recordings the orchestramade for Columbia Records during that time. While inPhiladelphia, Keith enrolled at Penn State University(but withdrew after taking one class) and taught at theSettlement Music School.Philadelphia Orchestra softball team, 1962. Keith Brownis in the center of the second row; concertmaster AnshelBrusilow is to his right. Trombonist Douglas Edelman, anextra player for the tour, is seated in the front row wearinga Beethoven sweatshirt.It was while with the Philadelphia Orchestra thatKeith reignited his youthful enthusiasm for baseball. Alongwith the orchestra’s concertmaster, Anshel Brusilow, heorganized a fast-pitch softball team. When the orchestrawent on tour, the team, sporting specially made uniformsof blue and white, played college intra-mural squadsand teams from other symphony orchestras. Keith was theteam’s pitcher, and on the orchestra’s 1962 United Statestour, the team went 6–2, including a 22–1 victory againstthe Youngstown Symphony that was suspended after fiveinnings, a sportsmanlike application of the “mercy rule.”In the summer of 1962, while teaching at the Aspen

Music Festival before joining the Met, Keith took hislove of baseball to the mountains. Harold C. Schonberg,the celebrated music critic of the New York Times, wrotea lengthy article about a faculty/student softball game thatKeith organized. Keith’s dominant, competitive spirit wasevident from the start,Keith Brown pitched for the faculty. He wastrombonist with the Philadelphia Orchestra andgoes to the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra this yearas first trombone. He is a well-built young man whohits a long ball (a switch hitter, yet), throws a fasterone, and in general handles himself on the ball fieldlike a semi-pro. While he was pitching, the scorein three innings was Faculty 12, Students 0. Bymutual request, he was removed from the moundand another faculty member went in. After the nextinning, the score was Faculty 12, Students 11.6Schonberg reported that the Dean of the Aspen musicschool, Norman Singer, took “a dim view of musiciansplaying baseball, and has constant visions of the diamondlittered with expensive fingers and arms, disconnectedfrom their respective bodies.” The game played on.On April 5, 1962, the Metropolitan Opera Orchestraheld the final rounds of its audition for associate firsttrombone. The Met, still at the old opera house onBroadway between 39th and 40th Streets, was a covetedjob then as it is now. After hearing eight players in the semifinal round, the committee agreed to advance three for asecond, final hearing. One was a player who, a year later,would begin a nearly thirty-year career as bass trombonistwith the American Brass Quintet, Robert Biddlecome. Yes,Robert Biddlecome, who at the time of the Met auditionwas playing tenor, not bass trombone. Another was GlennDodson, then principal trombonist of the New OrleansSymphony who, three years later, won the position ofKeith Brown at the Metropolitan Opera, 1964.assistant principal trombonist of the Chicago Symphonyand a few years later, succeeded Henry Charles Smith IIIas principal of the Philadelphia Orchestra. The third wasKeith Brown, then associate principal trombonist of thePhiladelphia Orchestra. The three played a final round foran audition committee of three staff conductors (GeorgeSchick, Joseph Rosenstock, Jean Paul Morel) and twomembers of the trombone section (Roger Smith, principaltrombone, and John Clark, bass trombone). The resultwas clear. “After playing a second time, the vote wentunanimously to Keith Brown, with Dodson placed secondand Biddlecome third,” Metropolitan Opera ManagerFelix Eyle wrote in his memorandum to the Met’s ArtisticAdministrator, Robert Herman. “Mr. Brown was offeredKeith Brown was one of the greatest people I have ever met. He was invited toPuerto Rico by the great Pablo Casals and for many years he touched the livesof so many people there with his kindness and musicianship. Many of us decidedto travel thousands of miles to come to study with him at Indiana Universitywhere he gave us so much. I remember that my lessons with him were alwaysvery early in the morning and no matter how early I woke up, he was in hisstudio practicing earlier than me. We will always remember you, Maestro!– Miguel RiveraTrombonist, Puerto Rico Symphony and Casals Festival OrchestraInternational Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net-17-

Pablo Casals and Keith Brown, c. 1971.and accepted the contract.”7 Keith Brown, trombone rockstar, was 29 years old.After joining the Met (where he played from 1962 to1965), Keith took over leadership of the orchestra’s softballteam. While it didn’t enjoy the success of the PhiladelphiaOrchestra team, it received copious coverage while playinggames during the opera company’s annual spring tour. NewYork’s second “Mets” team (Keith always referred to theopera’s team as the “New York Met” but writers usuallyfailed to make the subtle difference in name between theMet and professional baseball’s New York Metropolitans,known as the Mets) was the subject of another article bySchonberg,8 but it was not only the New York Times thatreported on Keith and the Met Opera’s softball team.Sports Illustrated reported on the team twice, in 1963 and1965, each time singling out Keith Brown as the team’s starplayer. “After him,” the leading sports periodical opined,“the class falls off sharply.”9 Sports Illustrated? A majorsymphony orchestra trombone player inside its pages? Thisdoesn’t happen every day.10 Keith managed to get the Metto pay for uniforms and equipment, and was the recipientof the orchestra’s Anthony Bliss/Rudolph Bing PerpetualChallenge Trophy in each of his three years in the orchestra,given annually to, as Keith recalled, “the person in theorchestra who did the most for the organization outside ofperforming.”11 Upon his leaving the Met in 1965, he waspresented with a large trophy, inscribed, “Keith Brown: Toan Outstanding Sportsman and Wonderful Colleague.” Thetrophy held pride of place in his home office.Keith’s annual appearance with the Casals FestivalOrchestra was an event he treasured. He was often reunitedwith old friends he had worked with in other connections,including Robert Nagel (trumpet), Byron Peebles, Lewisvan Haney and Robert Harper (trombones), and HarveyPhillips (tuba). A photo of Keith playing for Casals proudlyhung in his studio. Through the haze of an underexposedimage, Casals can be seen conducting Keith, pipe in hisleft hand, the two men lost in music. What a moment. Whatwas he playing? The Sarabande of Bach’s Cello Suite 6?Faure’s Après un rêve? I never thought to put the questionto Keith. I wish I had.Not only was Keith Brown an excellent trombonist and musician, buthe was able to utilize his vantage points to pinpoint voids of pedagogyand performance that offered great meaning to students and performersworldwide. His numerous publications, including his ten-volume set oforchestral excerpts for trombone, contributed mightily to the musical andtechnical development of thousands of aspiring musicians and is but oneexample of the outstanding legacy of Keith Brown.— M. Dee StewartProfessor of Trombone (retired), Indiana University-18-International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net

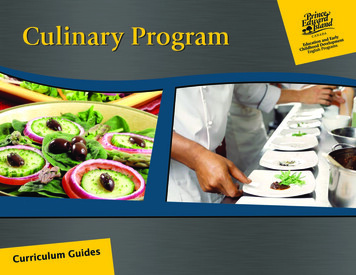

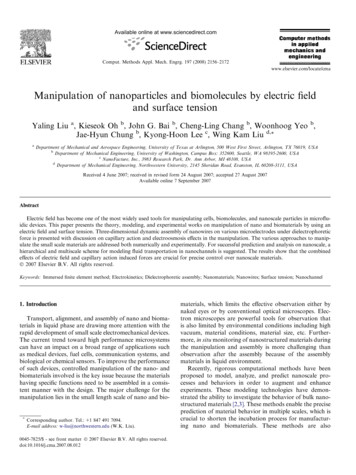

New York BrassQuintet promotionalbrochure, 1959. Leftto right: FrederickSchmitt, Keith Brown,Harvey Phillips, JohnGlasel, Robert Nagel.Chamber musicFounded in 1954 by trumpeter Robert Nagel, the NewYork Brass Quintet was in need of a new trombonist whenErwin Price left the group in 1958. When Keith and LesleeBrown moved to New York City that summer, RobertNagel asked Keith to join the quintet, and Harvey Phillipsrecalled that “his playing had a profound effect on the othermembers.”12 It was Keith who insisted that if the groupwas to succeed, it needed to branch out from its primarywork of giving concerts for children under the auspices ofYoung Audiences, Inc. All of the quintet’s members wereactive New York freelancers; Keith encouraged the group’smembers (in addition to Nagel, Brown, and Phillips, theNYBQ at that time included John Glasel, trumpet, andFrederick Schmitt, horn) to devote their primary energyto the quintet, seek out artist management, and increaseconcert bookings. Another result of Keith’s passionateadvocacy was the group’s self-produced master recordingfor an album, recorded in the spring of 1959. The tape wasquickly picked up by Golden Crest and released as “TheNew York Brass Quintet in Concert.” The album includeda performance of Eugene Bozza’s Sonatine for brass whicheven today—sixty years later—remains one of the mosthighly respected interpretations of the piece.From 1957 to 1969, Keith was associated with theAspen Festival, as its trombone teacher and principaltrombonist of the festival orchestra. In 1962, the AspenFaculty Brass Quintet was formed with Robert Nageland John Head, trumpet (at that time he was principaltrumpet of the Birmingham Symphony, and, beginningthe following year, the Atlanta Symphony), Philip Farkas,horn, Keith Brown, trombone, and Harvey Phillips, tuba.13For Keith, the quintet was a reunion of sorts since itbrought him back with his friends from his year with theNew York Brass Quintet, Nagel and Phillips. It also lookedahead to the years (1971–1982) when Brown, Farkas, andPhillips would serve together on the brass faculty at IndianaUniversity. For several programs in the Aspen quintet’sinaugural season, the group was expanded to a sextet withthe addition of trombonist Mildred Kemp, who joined theLouisville Orchestra in 1957 before moving to New YorkCity to play in Leopold Stokowski’s American SymphonyOrchestra and a freelance career that included playingBroadway shows and a tenure in the Goldman Band.14Through a number of connections—his friendship withBob Nagel, and his recordings for Columbia Records withthe Philadelphia Orchestra—Keith participated in a seriesof recordings conducted by Igor Stravinsky. These included“Igor Stravinsky Conducts, 1961,” which included theOctet for Wind Instruments (Richard Hixon played basstrombone) and a second recording of the Octet conductedby Stravinsky that appeared on “Igor Stravinsky ConductsMusic for Chamber and Jazz Ensembles” (recorded in1971) along with Ragtime for 11 Instruments and theConcertino for 12 Instruments.Aspen Music Festival, 1965. Left to right: Keith Brown, Mildred Kemp, Harvey Phillips, Philip Farkas, John Head, Robert Nagel.International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.net-19-

I came to Indiana Universitywithout realizing what a hugeinfluence Keith Brown would haveon my life, let alone my career asa trombonist. He was incrediblysupportive of his students,including me. I felt I could go tohim at any point with any issue(personal, school, registrar, etc.)and he would help me resolve thesituation. We spent many lessonssimply talking about sports andhow it relates to music. He wouldcompare fielding a ground ball toplaying Bolero. “Play the ball,don’t let the ball play you!” hewould say after a tentative start toBolero. He just knew what to sayto connect with me.— Stephen LangeTrombonist, Boston Symphony Orchestra-20-International Trombone Association Journal / www.trombone.netFor three years (1971 to 1973) Keith was the trombonistat the Marlboro Music School and Festival in Vermont.Founded in 1951 by pianist Rudolf Serkin, Marlboro was—and remains today—the premier chamber music festival in thecountry. Trombonists were called upon sparingly at Marlboroand were mostly used on twentieth century repertoire. ArthurKerr was the first trombone player at Marlboro (1953) andhe was followed by players including Douglas Edelman andDonald Hunsberger (1961), Alan Raph and Ralph Sauer(1964), and John Swallow (1965–1970). Keith recalledhis summers at Marlboro with special affection. From1969–1988, Keith performed regularly with the ChamberMusic Society of Lincoln Center. Among his many concertswere all-Stravinsky programs conducted by Michael TilsonThomas that featured the Ragtime for 11 Instruments, andone conducted by Leonard Bernstein that included theConcertino for 12 Instruments and the Octet; David Taylorplayed bass trombone alongside Keith. Symphony, opera,chamber music. Keith did it all with the very best.Arranging and editingJ. S. Bach, Cello Suites, edited by Keith Brown, IMC 3148,1972 (author’s copy). The date in the upper left-hand corner(April 12, 1974) is in Keith Brown’s hand, an indication of thedate when the movement needed to be prepared for a lesson.In 1963, Keith was approached by International MusicCompany (IMC) of New York City to embark on a projectto arrange and edit music for trombone. He agreed,and from that time through 2001, he published overeighty publications. As mentioned earlier, these includedbooks of études and studies that are staples of trombonepedagogy including those by Kopprasch, Blume, Slama,Werner, and Stephanovsky. He arranged dozens of solos aswell as music for four trombones (th

Bring your Brown books. Yellow, red, blue, and green. But bring the others, too. You never know.” “Yes,” you said. “You never know.” “Jim and Andrea are coming. Dan, too. Oh, and bring a music stand.” You paused, so as not to sound too eager. Then, “I’ll be there. I’ll have my