Transcription

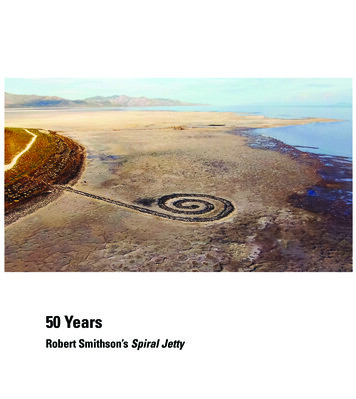

50 YearsRobert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty

The Utah Museum of Fine Arts is honored to work in collaboration with Dia Art Foundation, Holt/Smithson Foundation, and Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College to preserve, maintain,and advocate for this masterpiece of late twentieth-century art and acclaimed Utah landmark. Dia ArtFoundation is the owner of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), and leases the lake bed where theearthwork is located from the State of Utah Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands.Support for this collection of essays was provided in part by the Marriner S. Eccles Foundation andThe Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

50 YearsRobert Smithson’s Spiral JettyIn 1970, Robert Smithson visited Utah and createdthe iconic earthwork Spiral Jetty, a 15-foot-widespiral of black basalt rocks and earth coilingmore than 1,500 feet into Great Salt Lake. It is amasterpiece of late twentieth-century art, drawingvisitors from around the world. But because it isuniquely positioned within Utah’s landscape, it hasa particularly rich relationship with our community.Over the past fifty years, we Utahns have beendeeply entwined with this work. Not only doesthe earthwork gain meaning and significance witheach of our intimate experiences with it, but ourstate’s land and water use policies deeply affect itschanging environmental context. What do the pastfifty years of Spiral Jetty tell us about ourselves?How will this earthwork, and our relationship withit, change over the next fifty years?On the occasion of Spiral Jetty’s fiftieth year, theUtah Museum of Fine Arts invited four brilliantUtahns to share their perspectives on SpiralJetty. The following essays are included in thiscommemorative booklet.Smithson Is Elsewhere: Robert Smithson at theUniversity of UtahAnnie Burbidge Ream, Assistant Director ofLearning and Engagement and Curator ofEducation, Utah Museum of Fine ArtsVIOLCraig Dworkin, Professor of English, Universityof UtahSpiral Jetty as a Witness to ChangeJaimi K. Butler and Bonnie K. Baxter, Ph.D.,Coordinator and Director, Great Salt Lake Institute,Westminster College

Smithson Is Elsewhere:Robert Smithson at theUniversity of UtahAnnie Burbidge ReamAssistant Director of Learning and Engagementand Curator of Education, Utah Museum ofFine Arts“This is sort of the door. At first you notice right atthe back that it’s green, right? There’s not reallymuch you can say about it, I mean it’s just a greendoor. We’ve all seen green doors at one time inour lives. It gives out a sense of universality thatway, a sense of kind of global cohesion. The doorprobably opens to nowhere and closes on nowhereso that we leave the Hotel Palenque with this closeddoor and return to the University of Utah.”– Robert Smithson, Hotel Palenque, January 24, 1972Fine Arts Auditorium, University of UtahRobert Smithson is best known for Spiral Jetty,his 1,500-foot-long, 15-foot-wide earthwork ofbasalt rocks that extends out into Utah’s Great SaltLake at Rozel Point. However, the large earthworkis not the only evidence of Smithson in Utah. TheUtah Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collectionhas several works of art by Smithson includingphotographs, paintings, collages, drawings andan original 1970 copy of the film Spiral Jetty thatwas recently rediscovered in the archives of theUniversity of Utah’s Marriott Library. Lesserknown is that in 1972 Robert Smithson was appointed Visiting Professor in the Department ofArchitecture at the University of Utah.In 1970, the chair of the University of Utah’sDepartment of Architecture Robert Bliss (1921–2018) and artist and architect Anna Campbell Bliss(1925 – 2015) were among some of the first to seeSpiral Jetty. Bliss and Smithson had a mutual friend,Jan van der Marck, then curator of the Walker ArtCenter in Minneapolis, who brought the Blissesto Spiral Jetty and eventually Smithson to theUniversity of Utah. A year later, in the fall of 1971,Bliss was introduced to Virginia Dwan, Smithson’sgallery representation, at a social function at SpiralJetty. Dwan approached him about the possibility ofSmithson spending some time at the University ofUtah in a teaching capacity. By November of 1971much of the paperwork was already in progressto appoint Smithson as a visiting professor. Initialconversations between Bliss and Dwan detail howSmithson would be on campus for several lecturesand to teach some graduate level workshops, aswell as to plan a major work. In his initial letterproposing the appointment to Edward Maryon, theDean of the College of Fine Arts, Bliss lists fourimportant benefits in accepting Virginia Dwan’sproposal to appoint Smithson to the position [fig. 1]:“1) we enhance the prestige of the department by having Smithson connected with it;2) we hope to convince Miss Dwan to fund a“chair” or at least support other artists in asimilar manner; 3) Smithson can make a goodcontribution to the College in lecturing andmeeting with art and architecture students;and 4) we do gain some income for ourdevelopment fund.”

fig. 1

Above left to right, fig. 2 and fig. 3 Next page, fig. 4On December 14, 1971 Robert Smithson wasofficially approved and appointed to the positionof Visiting Professor of Architecture for thecalendar year of 1972 [fig. 2 and 3]. Inspite of theexcitement and sense of possibility evident fromthe long trail of paperwork connected to Smithson’sappointment, his presence on campus was fleeting,comprising of only two events, a lecture titled HotelPalenque and a screening of his film, Spiral Jetty.On January 24th, 1972, standing on the stageof the Fine Arts Auditorium at the University ofUtah, Smithson presented Hotel Palenque to anaudience of approximately 250 students, faculty,and community members. In his talk, Smithsonshowed slides of an old, crumbling roadside hotelin the Chiapas region of Mexico, which he hadvisited with his wife, artist Nancy Holt, and galleryowner, Virginia Dwan in 1969. In a 42-minute slidepresentation, Smithson who, according to RobertBliss, was accompanied by a glass of Scotch,narrated 31 photographs he’d taken of the hotel inthe manner of a family vacation slideshow, flippingfrom one slide to another, analyzing the buildingsand the grounds in a deadpan manner.“Here we have some bricks piled up with sticks sortof horizontally resting on these bricks. And theysignify something, I never figured it out while Iwas there but it seemed to suggest some kind ofimpermanence. Something was about to takeplace. We were just kind of grabbed by it.”His meandering observations snake around theperiphery and range from the illuminating, to

the humorous, to the boring, simultaneouslystraddling understanding and complete nonsense.“You should be getting the point that I am tryingto make, which is no point actually,” commentsSmithson. Yet, Hotel Palenque is consistentwith the artist’s interest in entropy, human vs.geological timescales, and human impact on thelandscape in that it elevates the mundane spacesof the decaying hotel as places of importance,focusing special attention to details of cast-offbricks, un-built walls and empty swimmingpools. Rarely has so much thought been putinto a run-down building! Morevover, Smithsonpointedly disregards Palenque’s famous Mayanruins, mentioning them only once: “If you couldsee actually back there you might remotely beable to pick up a fragment of the Palenque ruins,the temples. the things we actually went there tosee, but you won’t see any of those temples in thislecture.” Disrupting the audience’s expectations,this chaotic yet acute study of a dilapidatedbuilding must have been quite an interestingencounter for the students and professors ofarchitecture.In his lecture, Smithson reminds us how carefuland creative consideration of peripheral placescan illuminate our time and how ultimately theycan be the most telling documents of who weare. Smithson’s tour through Hotel Palenque isnot a discovery of great conclusions, but ratherit highlights the enjoyment in discovering theoverlooked. More than a site and historical record,the Hotel Palenque lecture has morphed froma strange happening to a work of art now partof the permanent collection of the Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum. Unknown at the time, thislecture is now the primary trace of Smithson’slittle-known appointment at the University of Utah.Information about Smithson’s second engagementon campus is well documented on paper, but

absent in collective memory. Archival records forhis screening of the film Spiral Jetty (1970) includescribbled notes “leave for Utah” and “movie 3:00”in Smithson’s personal calendar on May 13 and 14,1972; as well as two small advertisements: a postercalendar and a postcard marketing the event.However, it remains a mystery if the film screeningactually happened. Robert Bliss had no recollectionof the event, and there doesn’t seem to be anyonewho remembers attending. (*If someone readingthis knows anything, please contact me!)Above, fig. 5According to the calendar highlighting events forthe museum (at the time named The University ofUtah Museum of Fine Arts, today the Utah Museumof Fine Arts), “Few Utahns know much about it[Spiral Jetty], but this situation can be remediedwhen a film about the Jetty and a lecture by Mr.Smithson will be presented in the Museum thisspring. Dates will be announced in a separatemailing” [fig. 4]. The separate mailing is a blue andwhite striped postcard that details “A showing ofMr. Smithson’s film about Utah’s famous SpiralJetty. Comments by Mr. Smithson on Sundayafternoon, 3:00 PM, May 14, 1972. MuseumAuditorium” [fig. 5]. These two marketing piecesseem so appropriate in their not-so-telling recordof an event that maybe occurred and maybe didn’t,an anti-climactic end to Robert Smithson’s time atthe University of Utah.Smithson’s appointment at the University of Utahconcluded with many of its initial expectationsunrealized. The Hotel Palenque lecture and ascheduled film screening came in place of anappointment that was initially anticipated to involvemultiple lectures, the planning of a new work, andteaching. The lack of collective memory aboutthe Spiral Jetty film screening and “commentsby Mr. Smithson” leaves one tantalized withthe possibilities of the unknown. With so muchdocumentation of Smithson through his prolific

writing, sketches and film documentation, missingeven the smallest record of the May 14, 1972 filmscreening leaves a heavy absence. Was the filmshown, was Smithson there, how many peopleattended, and what were their reactions to the film?What new understandings into the cut-short worldof Smithson could have been revealed? Why did anappointment that held so much promise evaporateinto such a small contribution? While the tracesof Smithson at the University of Utah are indeedghostly, there is something keenly intriguing abouthis persistent absence. His appointment, in the end,remains largely a phantom, resulting in few eventsand leaving even fewer traces. Yet, even if onecould see through the murky haze of history, it isuncertain that anything would be there. Smithsonwas elsewhere.This essay is an excerpt from Burbidge Ream’sMaster of Arts thesis of the same name through theDepartment of Art and Art History at the Universityof Utah detailing original research of Robert Smithson at the University of Utah including an oralinterview with Robert Bliss, in which some ofhis comments were summarized here.Serving as Assistant Director of Learning andEngagement and Curator of Education at theUtah Museum of Fine Arts, Annie Burbidge Reamoversees the administration of K-12 School andTeacher Programs, including planning, statistics,and reporting; curricular development; andmanages the Education Collection. In addition,Annie utilizes UMFA objects and resources tocreate hands-on, question-based experiencesfor teachers and students across the state ofUtah, as well as docent trainings emphasizingthe importance of experiential learning. Annieapproaches her work with the philosophy thatart is for everyone and with goals to assist in thedevelopment of visual literacy and cultivate criticalthinking, creativity, and curiosity. Annie has adeep love for American Art after 1960, especiallyLand art, and can be found exploring sites acrossthe West. Annie received the 2016 Utah MuseumEducator of the Year by the Utah Art EducationAssociation as well as the 2016 Pacific RegionMuseum Education Art Educator Award from theNational Art Education Association.

VIOLCraig DworkinProfessor of English, University of UtahThe gull swerves shoreward, her single wing’s skinswept back by the wind, curving to a thin ellipse . . .lips kissing out in puffing pouts, billowing swellsdistending, then concaving in a sudden exhalationand impulsive retreat, with the pistoned pantof pneumatic bellows rounded out in punchingbouts — the heaving beat of slung booms sungwith canvas slaps and snapping sheets — as theprowling prow ploughs the turfed surface of tilledsurf, a newly tilted cant briskly pitching to the bank,with high-skewed angles of yaw and little sign ofdamping, taking flight beneath the porous spumeconfused and calcinated white like fluid tufa;ranked rows advancing toward the scaw, acrossthe sunken causeway, refraining in hydrographiccanticles chanted like a choir of angels overyawning caverns in a chaos of cataclasmic chasms;reaching, zephyr impended, stressed pinionsstretched before each sudden collapse, the surfacesoon smooths iron flat, as if by the passing ofsome floating screed, then just as quick distressed,discrete — quills stalled in squalls of aqueous,scrawled calligraphs scripted by degrees like theligatured arabesques of some furious caliph’simpetuous, pent, tempestuous scrid decreed —flapped in fraught semaphores of repeated dilationand fleet diastolic release.assimilating smaller nodes, and then distending,purging in dispersion — the process cycling overagain in turn from ebbs attenuating in their driftto amalgamates subsuming; the surging spumein wroth, now rousing, spurged. Annealed by theunctuous slaver of the spindrift, the cambered hull,by nature punctual, was laved.Following the mesoscale’s sostenuto series ofdemotic avisos furiosos, in its isosmotic pressure,sailors sent lassos lashed as hawsers to provisos,the moorings anchored in desmostic, isoscelesrestraints, so soon cut through with Phrygianprecision up to the ricassos by the wuthered flayingof sustained fletched laminae against untenabletensile detrusion — slack lashings frayed toglossoscopic symptoms as the ship’s set sosslingto the subsequent stillness of the silted, calmsubstratum of capsizal’s newly ceilinged, quaggedSargasso Sea, which, were there some auditor,seems to be sospiring only with a basso’s soss infull remorse, while no salvatic band of virtuosos— or even any lone, late sospitator, redeeming,arising — accedes.The sailors’ signals of extreme distress, morsed inmorphing and repeated, urgent appeals, went, inbrief, unheeded.The boat, in short, floated upon the troubled waters.Its iron hog-chain, taut, maintained (so shallowhulled, the structure arched without a cinch to staythe sagging of the ark), despite the strain. Lacingtraceries of salt brine wove over waves on whichthey rose and fell in gliding float, slickly slipping,assuming thin synaptic threads of froth beforeBrigham Young’s pride and joy, the TimelyGull — the largest craft of any consequence toventure on the waters of the Great Salt Lake inthe decade since the middle of the century, whenStansbury launched the Salicornia, itself a firstrate frigate, consorted by a skiff, trafficking withstately dignity upon the bosom of those solitary

Finial scroll of a viol

waters, circumnavigating, to make his mensualmensuration of its bleak and naked blood-redshores, without even a single tree to relieve theeye as he surveyed the lacustrine topographythat framed the desolation’s stillness of the gravebelow the distant peaks — had been of a suddengale-ripped from its moorings at Black Rock and,in the heavy winter winds that rose in February’sfury, tossed upon the petrose shore above thescuttling waves, in splinters, staved. Piled by thestormwinds’ hostile pummel, the riven timberswould stay hidden by the self-same waters thathad made its construction a necessity when theysubmerged the spit that had bridged a herd-pathtrack to Antelope Island, until celebrating itssesquicentennial by raising up its beams abovethe brack again, in a palisade of paling stanchionsdriven in the sand. The deocculted pickets wouldappear to local shrimpers like the broken spearsof some defiant phalanx sparing with the sky.of Halkyn, who had captained steamships on theMississippi, navigating converts by the hundredsin pilgrimage up river to Nauvoo. Freighted in itsday with flagstone, cedarwood, and salt, The Gullwas meant to carry livestock, ferrying Young’sherds in seasonal rotation from periodic pastureson the long-grassed Lake isles and, against theimpendent threat of Ute attack on shore, deliverthem with swift elusion to the sanctuary of somesaline keep, secure beyond defile, dangling at itsscrap-iron anchor, long stay apeek, in tantalizingappropinquity, just out of earshot of the rancorouschorus of the battle-cries and war-whoops, evenfor the keen-eared quadrupeds. The skittish phobicbovine, though, would soon lapse back, amnesiac,settled in their placid taciturnity: impassively atease, indifferent to the spectacle of distant hoofstirred dust that shrouded raided ranching plats,immune in their abeyance, preoccupated only withthe tranquil rustle of the breeze amid gramineæ.Before Young fitted up his ship with grommetedgarments of flaxen canvas waxed as sailing cloth,allowing the breath of god to speed it towardsits purpose, two carthorses, martingaled like thedolphin-striker of The Gull herself, with tackleharnessed to a treadmill, in turn connected to astern wheel, propelled the ship; the pair of equinetrekkers walked upon the water, hyaline eyes fixedin the distance on the reflectance of a blindingluminescent destination — ever receding andnever attained. As they ambulate, clouds of midges,risen by the morning warmth, swarm and clamber;brine flies glaze the shoreline; the margin of thelake, in haze, conflates the horizon’s halation withits minimal hypsographic measure. The horsemarines plod on across the halcyon waters ofthe salinated inland sea.Assuming that the average dairy cow extends toa length of around one-hundred inches, and thatthey boarded arkwise, two-by-two, in double ranksupon the barge’s tarred and mitred planks, andthat the carlin of the Gull spanned a full forty-fivefeet, as widely reputed, it could have carried ascore of cattle at a time in full continual transport.Supposing that the coil of Robert Smithson’sSpiral Jetty were the scroll finial of a seventeenthcentury viola da gamba, the strings of that mightyinstrument would stretch to two-thousand, onehundred-and-seventy-six feet, almost thirteentimes the length of the intestine obtained froma prodigious specimen of a full-grown ox orsteer, locally prized for the high collagen of itssubmucosa and externa. With the peritoneumsoaked and serosa scraped and the surface steepedfor days in a potash of potassium hydroxide, thetight-wound entrails can sound a dulcet timbre,almost vocal, when strung as strings, amber huedand rosinous, attached from box to bridge. TheYoung’s cattle-barge had been designed andpiloted by pioneer Dan Jones, a Welshman out

lowest of those catgut cords would call for thesacrifice of roughly 184,320 animals, which wouldentail nine-thousand two-hundred and sixteenvoyages, accordingly, of the barge to deliver (anddiscounting the thousands calved in the intervalso as not to leave the island vacant). Cruising attwo horsepower, ship stowed to bale-cube capacityat twenty register tonnes, it would have taken DanJones a decade and three full months of steadysailing, in continuous loops from shore to shorewithout pause, to accomplish the conveyance.In order to maintain a baroque-era pitch, in eventemperament tuning, the D string of that giganticjetty bass viol would require a tension of almostfourteen billion Newtons. The force would thusbe four-thousand times the winds — deafeningin themselves, coursing the shore and raking thesands — that once careened the great and mightyhull of the devastated Timely Gull in that fatalwinter gale of 1858.Craig Dworkin is the author of over a half-dozenbooks of poetry, including, most recently: ThePine-Woods Notebook (Kenning Editions, 2019);DEF (Information As Material, 2017); 12 ErroneousDisplacements and a Fact (Information As Material,2016); Alkali (Counterpath, 2105); and Chapter XXIV(Red Butte Press, 2013). He teaches literary historyand theory in the Department of English at theUniversity of Utah and serves as Founding Editorto the Eclipse archive eclipsearchive.org .

NOTEShog-chain: Peter G. Van Allen: “Sail and Steam: Great Salt Lake’sBoats and Boatbuilders, 1847-1901,” Utah HistoricalQuarterly 63: 3 (Summer. 1995): 201.extreme distress and repeated urgent appeals: The Oxford EnglishDictionary, 2nd Edition, ed. J. A. Simpson and E. S. C.Weiner (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989): sv. “S.O.S.”.pride and joy: Annie Call Carr, Editor, for The Daughters of UtahPioneers: East of Antelope Island (Kaysville: DavisCounty Company, 1948): 29.consequence: Simon F. Kimball: “Early-Day Recollections ofAntelope Island,” Improvement Era Vol. X, No. 5(March, 1907): 336.frigate: Howard Stansbury: An Expedition to the Valley of the GreatSale Lake of Utah: Including A Description of its(Salt Lake City: Andrew Jensen History Company,1920): 660; cf. David E. Miller: “Great Salt Lake: AHistorical Sketch,” Utah Geological and MineralSociety Bulletin 116 (June, 1980): 12.Lake isles: Bill Durham: “Sailors of the Briny Shallows,” Westways49 [Los Angeles: Automobile Club of SouthernCalifornia (March, 1957)]: 52.attack: see Thomas G. Alexander: Brigham Young and the Expansion of the Mormon Faith (Norman: University ofOklahoma Press, 2019): 292; Richard Tomas Ackley:“Across the Plains in 1858,” Utah Historical Quarterly,ed. J. Cecil Alter Vol. IX (1941); Peter Gottfredson(Editor): History of Indian Depredations in Utah (SaltLake City: Skelton, 1919): passim.Geography, Natural History, And Minerals, and anscrap-iron: Topping, op. cit., 205.Analysis of Its Waters: With an Authentic Account ofscroll finial: see Ephraim Segerman: “The Sizes of English Violsthe Mormon Settlement (Philadelphia: Lippincott,Grambo & Co., 1852): 11. Stansbury overstates theclass considerably; a more modest yawl or dorie wouldhave been more accurate [see Gary Topping: Great SaltLake: An Anthology (Logan: Utah State UniversityPress, 2002): 224].Salicornia et seq.: Stansbury, op. cit.Black Rock: “Low Water of Great Salt Lake Reveals Ghosts of thePast,” Salt Lake Tribune (18 August, 2014).submerging the spit: Topping, op. cit., 208; cf. Marlin Stum:Visions of Antelope Island and Great Salt Lake (Logan:Utah State University Press, 1999): 125.spears: Brian Mullahy: “Great Salt Lake Gives Up ‘Mysteries’ asWater Drops,” KUTV (5 November, 2014).sailing cloth, et seq.: see President Young’s journal of 30 January,1854: “I christened her the Timely Gull. She is forty-fivefeet long and designed for a stern wheel to be propelled by horses working a treadmill, and to be usedmainly to transport stock between the city andAntelope Island.” Other accounts describe the gulland Talbot’s Measurements,” Galpin Society Journal48 (March, 1995): 33-45.prodigious specimen: see Black’s Veterinary Dictionary, ed.Edward Boden, 19th Edition (Lanham: Barnes & Noble,1998): 282.collagen: Voichita Bucur: Handbook of Materials for String MusicalInstruments (Switzerland: Springer, 2016): 482-486.potash: Bettina Hoffman: The Viola de Gamba, trans. PaulFerguson (London: Routledge, 2018): 43.amber: ibidem, 45.lowest: Atthanasio Kircher: Musurgia universalis sive ars magnaconsoni et dissoni in X. libros digesta, Lib. V (Roma:Corbelletti, 1650): 440.14,400: Sadly, this is almost fifty times the head available to Youngfrom his historic herd and an order of magnitude largerthan the common Church holdings at the time.baroque-era pitch: Bruce Haynes: A History of Performing Pitch:The Story of “A” (Oxford: Scarecrow, 2002).tension: the absolute mensur of a D string, in actuality, cannotpractically exceed 79cm given that its breaking point is“fitted-up as a sailing boat” [Journal History of thea tone lower at 88.7 cm, calculated from the limit ofChurch (25 June 1856), LDS Archives]; see also Stum,approximately 260Hz per metre, a value independentop. cit., 127.flagstone, cedarwood and salt: Andrew Jensen: Latter Day Saintof diameter [see Hoffmann, op. cit., 41].fatal winter: William Mulder: [untitled review of Norman F. Furniss:Biographical Encyclopedia: A Compilation ofThe Mormon Conflict: 1850-1859 (New Haven: YaleBiographical Sketches of Prominent Men and WomenUniversity Press, 1960)], History News 16 : 12in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Vol. II(November 1960 – October, 1961): 145.

Spiral Jetty as aWitness to ChangeJaimi K. Butler and Bonnie K. Baxter, Ph.DCoordinator and Director, Great Salt Lake Institute,Westminster CollegeGreat Salt Lake tells a story about change overtime. A salty lake such as this modern one hasexisted in the bottom of the Bonneville Basin forthe better part of a million years. Occasionallywaters rose, held in by glaciers, such as enormousLake Bonneville during the last Ice Age. But whenthe Earth was warmer, only a shallow salty puddleremained, like Great Salt Lake. The modern lakehas experienced the interventions of humans onits shores, damming and segmenting its brine fortheir purposes. One human, Robert Smithson,intervened by creating artwork on the lakebed toinspire others. His Spiral Jetty, likewise, commentson change over time.Smithson used scientific and mathematicallanguage when he planned and executed SpiralJetty, built into the pink water of Great Salt Lake1.Equation. Coordinates. Desiccation. Variable.Entropy. Bacteria. Matrix. Cubic. Scale. In fact,he had researched physical parameters of thesite in thinking about aesthetics. Inspiration camefrom science, but how much did he understandabout this analytical system of knowing? Did heknow that terminal lakes vacillate in elevation?Was he aware that rivers feeding the lake bringsmall amounts of minerals that concentrate in theterminal lake over time? Did he comprehend thecoloration of the water would change seasonallyas the microorganisms were affected by temperature and salinity? Could he have predictedthe impacts of humans in the form of climatic1Smithson, P., & Smithson, R. (1996). Robert Smithson: thecollected writings. Univ of California Press.

change and water diversions? Perhaps his artworkunderstands the answers to these questionsin a way that the artist could not through itsexperiences of Great Salt Lake over 50 years.We would love to ask Spiral Jetty about itsobservations of environmental change. Forexample, it is perplexing that Smithson nevercommented on a frequent occurrence, noted bytoday’s visitors to the artwork, of American WhitePelicans soaring in the skies above the SpiralJetty. These birds migrate to Utah from theiroverwintering grounds in Mexico to breed on thenearby, remote, and solitary Gunnison Island.Pelicans now arrive in March to begin their annualbreeding, yet as Smithson toiled on this earthworkin April, he never wrote about these majestic birds.We wonder if the pelicans now arrive earlier in theseason, a signature of climate change.Over the last 50 years, Smithson’s Spiral Jettyhas witnessed dramatic changes to the lakelandscape as an increasing human populationbegan draining the watershed. While the landart hid beneath the flooded brine in the 1980s,reemerging almost 20 years later, the next 50 yearswill likely hold something very different. Climatestudies on the southwestern United States suggestthat Spiral Jetty will see an increase in temperaturethat will impact our water supply. Coupled withprojected increases in population, Great Salt Lakehas little hope of recovery. As the lake shrinks, andmore shorelines are exposed, extensive dust willaffect the air quality. Spiral Jetty will sit on a drylakebed and remember when water used to lap thewhirling basalt.The pelicans are victims of this change. Thisdownward trajectory of this shallow lake hasconnected the island to land, resulting in theencroachment of predators to what was a safehaven. Also, water availability has decreasedin nearby feeding grounds, making fish scarce.The pelicans’ demise is obvious at the site of theartwork where you may find carcasses of babypelicans that cannot fly far enough to catch foodfor themselves. Smithson noted that the SpiralJetty was “intimately involved with those climatechanges and natural disturbances.”As climate change progresses, and sciencesuggests interventions, we should be movedto activism. Once art advocates did what scientists alone could not; in 2008, through an initiativetaken up by Smithson’s widow, Nancy Holt,thousands of Spiral Jetty admirers wrote lettersto the state of Utah to prevent an oil drillingoperation on Great Salt Lake. Perhaps this landart can once again call forward stewards of thelandscape who can advocate for climate changesolutions for the human residents of the valley,the pelicans of Gunnison Island, and RobertSmithson’s Spiral Jetty.

Above, PELIcam Image courtesy Great Salt Lake Institute atWestminster College and the Utah Division of Wildlife ResourcesBaxter and Butler have spent a combined fourdecades studying the biology of Great SaltLake and much of it at Smithson’s Spiral Jetty.While Butler explores the birds and bugs, Baxterresearches the foundational microbiology. RozelBay hosts this land art, but it also is a site of theauthors’ astrobiology studies with NASA, paleontological explorations in the tar seeps, and artscie

The following essays are included in this commemorative booklet. Smithson Is Elsewhere: Robert Smithson at the University of Utah Annie Burbidge Ream, Assistant Director of Learning and Engagement and Curator of Education, Utah Museum of Fine Arts VIOL Craig Dworkin, Professor of Englis