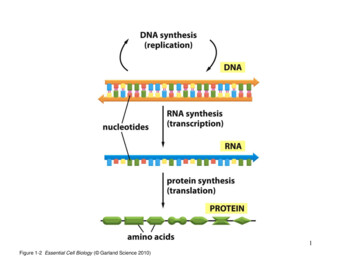

Transcription

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021THE WHOESSENTIALMEDICINES LISTANTIBIOTIC BOOKImproving antibiotic AWaReness

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021 WHO 2021. All rights reserved. This is a draft version intended for public comment. Thecontent of this document is not final, and the text may be subject to revisions before its finalpublication. This document may not be reviewed, abstracted, quoted, reproduced,transmitted, distributed, translated or adapted, in part or in whole, in any form or by anymeans without the permission of the World Health Organization. This document includesproposed guidance for prescribing antibiotics; however since this document is a draft, it shouldnot be used for the purpose of prescribing antibiotics or for any other purpose, except publiccomment. This document is being published without warranty of any kind, either expressed orimplied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies exclusively withthe reader. In no event shall WHO be liable for any damages arising from its use.

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021Table of contentsINTRODUCTION . 1Improving the use of antibiotics with the Handbook . 4PRIMARY HEALTH CARE . 19Bronchitis . 20Acute otitis media . 24Pharyngitis . 30Sinusitis - acute. 38Dental infections . 44Localized acute bacterial lymphadenitis . 58Bacterial eye infections . 63Trachoma . 88Community-acquired pneumonia – Mild. 93Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease . 102Infectious diarrhoea / gastroenteritis . 106Enteric fever . 114Skin and soft tissue infections - Mild bacterial impetigo, erysipelas and cellulitis . 119Burn wound-related infections . 127Wound and bite-related infections. 132Sexually Transmitted Infections – Chlamydia urogenital infection . 142Sexually Transmitted Infections - Gonococcal infection . 150Sexually Transmitted Infections - Syphilis. 158Sexually Transmitted Infection - Trichomoniasis . 170Urinary Tract Infection - Lower . 176HOSPITAL FACILITY . 183Sepsis in adults . 184Sepsis in neonates ( 28 days) and children (28 days–12 years) . 198Bacterial meningitis . 212Community-acquired pneumonia – Severe . 222Hospital-acquired pneumonia . 234Intra-abdominal infections - Acute cholecystitis and cholangitis . 242

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021Intra-abdominal infections - Liver abscess - pyogenic . 251Intra-abdominal infections - Acute appendicitis . 260Intra-abdominal infections - Acute diverticulitis . 269Intra-abdominal infections- Clostridioides difficile infection. 275Urinary Tract Infection - Upper . 281Acute bacterial osteomyelitis. 290Septic arthritis . 299Skin and soft tissue infections - Necrotizing fasciitis . 307Skin and soft tissue infections - Pyomyositis . 313Febrile neutropenia . 318Surgical prophylaxis . 328RESERVE ANTIBIOTICS . 334Overview . 335Cefiderocol . 339Ceftazidime avibactam . 344Fosfomycin (intravenous). 349Linezolid . 355Meropenem vaborbactam . 359Plazomicin. 363Polymyxin B and colistin (polymyxin E) . 367FORMULARY . 373ADULTS . 373CHILDREN . 378GLOSSARY . 384REFERENCES . 390

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 20211INTRODUCTION2345There is a clear need for simple resources to improve the quality of antibiotic prescribing globally.The Handbook was designed as a tool to make the WHO model Essential Medicines Lists foradults and children (EML and EMLc) of antibiotics more helpful to prescribers and to update theprevious WHO 2001 WHO Model Prescribing Information (1).6Aim and Scope7891011121314151617The aim of the Handbook is to provide short, clinical guidance on the management of commoninfections, including recommendations for empiric antibiotic treatment at the first clinicalpresentation and when a “No antibiotic” approach is appropriate. Guidance is given on the choiceof antibiotics that should be used to treat the most likely bacterial pathogens causing eachinfection in adults and children, the dosage and treatment duration.The Handbook is intended for all health care workers who prescribe and dispense antibiotics inhigh-, middle- and low-income settings in both the primary health care and the facility/hospitalsetting. It aims to complement WHO’s Policy Guidance on Integrated Stewardship Activities andthe Toolkit for health care facilities in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (2). TheHandbook is not intended to replace existing local and national antibiotic prescribing guidelinesand clinical judgment, but to provide simple guidance where currently none is available.18Methodology1920212223The antibiotic treatment recommendations outlined in this Handbook are based on reviews ofthe evidence undertaken for the 2017, 2019 and 2021 updates of the EML and EMLc. TheEML/EMLc provide a list of safe and effective antibiotics that should be available and affordablefor patients globally. The EML Handbook provides guidance on how to best use these antibioticsbased on the principles of the AWaRe framework.Box 1 – Principles of the AWaRe framework1) Maximizing clinical effectiveness2) Minimizing toxicity3) Minimising unnecessary costs to patients and healthcare systems4) Reducing the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance (i.e. prioritizing antibiotics thatare less likely to lead to antibiotic resistance in an individual patient and the community)5) Parsimony (i.e. avoiding the inclusion of many similar antibiotics)6) Simplification (i.e. favouring a smaller number of antibiotics that can be used to treatdifferent infections)7) Alignment with existing WHO guidelines1

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 202124252627The detailed reviews on the optimal choice of antibiotics to be used for each specific clinicalinfection were based on a standardised analysis by experts in evidence-based medicines fromMcMaster University (Hamilton, Canada) of systematic reviews, meta-analyses and clinicalpractice guidelines.28293031Details regarding the evidence underlying the recommendations and the methodology can befound here: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259481 43536The choice of antibiotics to use for each specific infection are formal recommendations based onthe evaluation made by the EML Expert Committee on the evidence presented for the EMLupdates or derived from existing WHO guidelines where available. The Handbook also providesguidance on diagnosis, symptomatic treatment and treatment duration based on non-systematicreviews of the literature and expert opinion.Box 2 – General considerations about the use of the HandbookAs with any general guidance document, the individual circumstances of the patients need tobe considered. Comorbidities (e.g. immunosuppression which changes the pathogens thatneed to be considered, or renal or hepatic insufficiency which may require dose adaption ofantibiotics), concomitant medications (risk of interactions), pregnancy and breastfeedingstatus (some antibiotics may be contraindicated), allergies (see separate chapter) and nationalregulations all may require an adaption of the guidance and it is the responsibility of eachprescriber to make sure that all these considerations are taken into account when prescribingan antimicrobial.Patients should be informed about the most common side-effects of the antibiotic, how itshould be stored and taken, how long to take it for and what to do if symptoms worsen or failto improve and how leftover antibiotics should be properly disposed of.37Structure3839There are separate chapters for 36 infections, divided for ease of use into “Primary health care”and “Hospital facility” sections fully acknowledging that there is overlap between these groups.4041424344454647Each chapter on a clinical infection includes: Background information. The pathophysiology, epidemiology, global burden, mostcommon pathogens and how to make the clinical diagnosis, including assessing diseaseseverity. Diagnostic tools. As the availability of diagnostic tools varies considerably in differentsettings, the empiric antibiotic recommendations are based on clinical signs andsymptoms. Relevant diagnostic tests (including imaging and laboratory tests) aresuggested based on the WHO’s Essential in-vitro Diagnostics List (EDL) (4). The list of tests2

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021484950515253545556 provided for each infection is not based on a formal assessment of their predictive value,but as a general guide of tests that could be clinically helpful, where available.Treatment. Guidance is given where appropriate for “No Antibiotic Care” includingsymptomatic management for low-risk patients with minor infections that do not needantibiotic treatment. First- and second-choice antibiotic options are then given whererelevant based on the EML/c and AWaRe system as well as other WHO guidancedocuments.Guidance on which infections may most benefit from targeted clinical microbiologysurveillance to help inform both local and national empiric antibiotic guidance.57585960Each chapter is complemented by an infographic containing a short summary of the mostimportant information (e.g. clinical presentation, diagnostic tests, treatment) separately forchildren and adults that can be rapidly and easily consulted when needed (see example belowof a children infographic).616263Further guidance is given on how the Handbook could be used to improve the use of antibioticsbased on general antibiotic stewardship principles.646566The Handbook also includes chapters on the Reserve antibiotics listed in the 2021 EML/c, theprinciples behind their selection and how these last-resort medicines should be used to preservetheir effectiveness.6768The Handbook is available both in a print and an electronic format. Simple, downloadableinfographics with the key information for end-users are also provided for each infection.3

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 202169Improving the use of antibiotics with the Handbook70Background7172737475About 90% of all antibiotics are taken by patients in the primary health care setting. It is estimatedthat around half of all antibiotic use is inappropriate in some way, such as the use of an antibioticwhen none is indicated, the choice of an antibiotic with unnecessarily broad spectrum (e.g.Watch instead of Access, see below), the dose, the duration of treatment, and the delivery orformulation of the antibiotic (3).76AWaRE777879808182This Handbook gives guidance on first- and second-choice antibiotics for common infections inline with the recommendation in the EML/c (4, 5). WHO has classified antibiotics into four groups,Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) and a fourth “Not Recommended” group. As well as theantibiotics on the EML/c, over 200 other antibiotics have now been classified intoAccess/Watch/Reserve groups to help inform local and national policy development andimplementation 8899091Access antibiotics have a narrow spectrum of activity, lower cost, a good safety profile andgenerally low resistance potential. They are recommended as empiric first- or second-choicetreatment options for common infections.Watch antibiotics are broader-spectrum antibiotics, generally with higher costs and arerecommended only as first-choice options for patients with more severe clinical presentations orfor infections where the causative pathogens are more likely to be resistant to Access antibiotics(e.g. upper urinary tract infections).Reserve antibiotics are last-choice antibiotics used to treat multidrug-resistant infections (seechapter on Reserve antibiotics).92939495The AWaRe system is also represented as a traffic-light approach: Access Green,Watch Yellow and Reserve Red (3). Simple graphics using the traffic light approach can beused to show the proportions of Access and Watch antibiotics used in settings such as acommunity clinic or pharmacy or as part of central monitoring of antibiotic consumption.96979899Countries, regions and districts are encouraged to use the Handbook as a basis for developingtheir own quality indicators and targets for safely reducing total levels of inappropriate antibioticprescribing to improve patient safety and care, while reducing resistant infections and costs forpatients and health systems.Box 3 – WHO target for the use of Access antibioticsTo promote responsible use of antibiotics and slow the spread of antibiotic resistance,the WHO Global Programme of Work includes a target that at least “60% of totalantibiotic prescribing at the country level should be Access antibiotics by 2023” (6, 7)4

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021100Box 4 – Improving the use of antibiotics with the Handbook1. No Antibiotic Care - safely reducing antibiotic use2. Improving Access use and reducing inappropriate oral Watch antibiotics3. Reducing the use of Not Recommended antibiotics4. Improving AWaRe-ness!5. Appropriate antibiotic dosing and duration1011. No Antibiotic Care - safely reducing antibiotic use102Key messages1. Most otherwise healthy patients with mild common infections can be treated withoutantibiotics as these infections are frequently self-limiting2. The risks of taking antibiotics when they are not needed should always be considered(e.g. side effects, allergic reactions, C. difficile infection, selection of resistant bacteria)103Management of low risk (mild) infections in primary health care104105106107108109110111112Most infections encountered in primary health care are not caused by bacteria (e.g. mostrespiratory tract infections have a viral cause) and therefore the patient will not benefit fromantibiotic treatment (Table 1). Even when the cause of the infection is bacterial, many infectionsare frequently self-limiting, with a low risk of severe complications and the benefit of antibioticsis limited (shortening of the duration of symptoms by usually only around 1 or 2 days). Mostotherwise healthy patients with mild infections may safely receive symptomatic treatment alone(e.g. anti-inflammatory medicines, pain killers or complementary medicines). Wheneverappropriate, guidance on diagnosing mild infections that can be treated with No Antibiotic Careis given in the Handbook.113114115Table 1 Common infections in primary health care that can be safely treated with No AntibioticCare (i.e. symptomatic management only) for mild cases – see individual chapters for moredetails.Infection(in alphabeticalorder)Acute diarrhoeaCan it be safely treatedwithout antibiotics?CommentYes, in the greatmajority of cases(unless there issignificant bloodydiarrhoea)Most cases do not require antibiotic treatment because theinfection is of viral origin and the illness is usually self-limitingregardless of the causative pathogen.The cornerstone of treatment is rehydration.5

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021BronchitisYesCOPDexacerbationsYes, in most mild casesDental infectionsYes, in most mild casesOtitis mediaYes, in most mild casesPharyngitisYes, in most mild casesSinusitisSkin and softtissue infections(mild)Yes, in most mild casesOnly for certainconditions and incertain patientsUrinary tractinfection (lower)Nearly all cases have a viral origin and there is no evidence thatantibiotics are needed.Most exacerbations of COPD are not triggered by bacterialinfections; only certain cases will benefit from antibiotictreatment.Dental treatment rather than prescribing antibiotics is generallymore appropriate in the management of dental infections.Most non-severe cases of acute otitis media can be managedsymptomatically and do not require antibiotic treatment.Most cases do not require antibiotics because the infection isviral.Most cases do not require antibiotics as the infections is viral. In cases of wounds at low risk of becoming infected, antibiotictreatment is not needed. In cases of animal bites, only wounds in high-risk anatomicallocations and patients with severe immunosuppressionbenefit from antibiotic treatment.In young women who are not pregnant, with mild symptomsand who may wish to avoid or delay antibiotic treatment,symptomatic treatment alone can be considered.116Only in a few patientswith no risk factors forcomplicated infectionsCOPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.117Are antibiotics 32133In 2006, the WHO proposed that the percentage of patients attending a primary health carefacility receiving an antibiotic should be less than 30% (9), but on average around half of patientspresenting with any infection in primary care still receive an antibiotic, contributing to theemergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (10). It is therefore important that bothhealthcare professionals and patients consider the risks of taking antibiotics when they are notneeded. These include the immediate risk of side-effects of the medicine, most commonlydiarrhoea or allergic reactions (such as a rash; see chapter on allergy to antibiotics) and rarelymore serious side effects. Bacteria in patients prescribed an antibiotic for a respiratory or urineinfection (as examples of infections for which antibiotics are often prescribed) commonly developantibiotic resistance to the prescribed (and other) antibiotics. They are also more likely to acquireresistant bacteria from other sources (other people, animals, food) and to transmits resistantbacteria to other people (8). Patients with infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria aremore likely to have a delayed clinical recovery(9). Furthermore, antibiotic treatment alters thepatient’s microbiota (i.e. all microorganisms that live in or on the human body), with potentiallong-term consequences (and increasing the risk of infection by Clostridioides difficile (abacterium that can cause severe diarrhoea).134Think D8 – before prescribing!Box 5 – Points to always consider when prescribingDiagnose – what is the clinical diagnosis, is there evidence of a significant bacterial infection?Decide – are antibiotics really needed? Do I need to take any cultures or other tests?6

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021Drug (medicine) – which antibiotic to prescribe - is it Access or Watch or Reserve? Are there anyallergies, interactions, or other contraindications?Dose – what dose, how many times a day, are any dose adjustments needed e.g. because of renalimpairment?Delivery – what formulation to use, is this a quality product? If intravenous treatment, when is StepDown to oral possible?Duration –for how long – what is the Stop Date?Discuss – inform the patient of the diagnosis, likely duration of symptoms, any likely medicine toxicityand what to do if not recovering.Document – write down all the decisions and management plan.1362. Improving Access use and reducing inappropriate oralWatch antibiotics137Key messages1351. The great majority of common infections in primary health care can be treated without anyantibiotics or with Access antibiotics2. Reducing the inappropriate use of Watch antibiotics is key to control antibiotic resistance138139The 68th World Health Assembly in May 2015 endorsed a global action plan to tackle antimicrobialresistance(10).Box 6 – The 5 objectives of the global action plan1) Improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance2) Strengthen surveillance and research3) Reduce the incidence of infection4) Optimize the use of antimicrobial medicines5) Ensure sustainable investment in countering antimicrobial resistance140141142143144145The Handbook therefore aims to address one of the objectives of the WHO global action plan“Optimize the use of antimicrobial medicines” with a focus on antibacterial medicines orantibiotics (antimicrobials also include antifungal, antiviral and antiprotozoal medicines). TheHandbook provides guidance on when not to prescribe antibiotics and – if indicated - whichantibiotics to prescribe for the most common infections. The Handbook focusses on the optimaluse of Access antibiotics as they remain the first choice options for the majority of infections.146147148149The Handbook recommends that 9 of the 10 (90%) most common infections seen in primaryhealth care can be treated safely with either no antibiotics or Access antibiotics (Table 2). Onlyone infection, acute bloody diarrhoea (dysentery), requires the empiric treatment withantibiotics in the Watch category (e.g. ciprofloxacin or azithromycin).150151Oral Watch antibiotics use globally is increasing. They are now very commonly taken by patientsin primary health care for minor infections (fever/cough/diarrhoea) in both high-income7

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021152153154155countries (HIC) and low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Reducing the inappropriate use ofboth oral and intravenous Watch antibiotics is a critical strategy for the global control of antibioticresistance, while ensuring vulnerable populations have continued or, where appropriate,improved “access to Access” antibiotics.156157Table 2 Common infections seen in primary health care settings and the antibiotic optionsrecommended in the HandbookInfectionBronchitisCommunity-acquired pneumonia(mild cases)Chronic obstructive pulmonarydisease exacerbationsDental infectionsInfectious diarrhoeabACCESS (A)/WATCH (W)No antibioticAAANo antibiotic or WFirst-choice antibiotic option (when anantibiotic is indicateda)No antibioticAmoxicillin orPhenoxymethylpenicillinAmoxicillin(for most mild cases the first choice issymptomatic treatment and antibioticsare not necessary)Amoxicillin orPhenoxymethylpenicillin(for most cases the first choice is adental procedure and antibiotics arenot necessary)Most mild non-bloody diarrhoea iscaused by viral infections andantibiotics are not necessaryFor acute severe bloodydiarrhoea/dysentery - Ciprofloxacin orAzithromycin orCefixime orSulfamethoxazole trimethoprimOtitis mediaPharyngitisSinusitisAAAAmoxicillin(for most mild cases the first choice issymptomatic treatment and antibioticsare not necessary)Phenoxymethylpenicillin orAmoxicillin(for most mild cases the first choice issymptomatic treatment and antibioticsare not necessary)Amoxicillin orAmoxicillin clavulanic acid(for most mild cases the first choice issymptomatic treatment and antibioticsare not necessary)8

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021Skin and soft tissue infection(mild cases)A158159160161Amoxicillin clavulanic acid orCefalexin orCloxacillinUrinary tract infection, lowerANitrofurantoin orSulfamethoxazole trimethoprim orTrimethoprim orAmoxicillin clavulanic acidaThe decision to treat is based on assessment of the patient and on a minimum set of criteria to start antibioticsdescribed in the chapters for each infection.bOnly oral antibiotic options are reported here.ACCESS antibiotics are indicated in green, WATCH antibiotics are indicated in yellow.1623. Reducing the use of Not Recommended antibiotics163Key messages1. The wide use of fixed-dose combinations that are not compatible with the EML and notapproved by the major regulatory agencies is of concern and their used should be reducedas these combinations may result in increased toxicity and selection of resistance.2. The EML has now developed a list of fixed-dose combinations whose use is stronglydiscouraged 165166167168169170In some countries there is a substantial use of fixed-dose combinations of antibiotics, whichcontain two or more agents in a single formulation and recent data suggest they represent up to20% of global antibiotic prescribing, especially in middle-income countries(11). Some fixed-dosecombinations of antibiotics are well established (e.g. sulfamethoxazole trimetho

THE WHO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES LIST ANTIBIOTIC BOOK – DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT – NOVEMBER 18, 2021 1 1 INTRODUCTION 2 There is a clear need for simple resources to improve the quality of antibiotic prescribing globally. 3 The Handbook was designed as a