Transcription

Instructor’s Resource ManualUnderstanding AbnormalBehaviorEIGHTH EDITIONDavid Sue / Derald Sue / Stanley SueRevised by Fred W. WhitfordMontana State UniversityDavid SueWestern Washington UniversityDerald Wing SueTeachers College, Columbia UniversityStanley SueUniversity of California, DavisHOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON NEW YORK

Vice President and Publisher: Charles HartfordSponsoring Editor: Jane PotterDevelopment Editor: Laura HildebrandEditorial Associate: Liz HoganProject Editor: Aileen MasonEditorial Assistant: Susan MiscioMarketing Manager: Laura McGinnMarketing Assistant: Erin LaneCopyright 2006 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.Houghton Mifflin Company hereby grants you permission to reproduce the Houghton Mifflin materialcontained in this work in classroom quantities, solely for use with the accompanying Houghton Mifflintextbook. All reproductions must include the Houghton Mifflin copyright notice, and no fee may becollected except to cover the cost of duplication. If you wish to make any other use of this material,including reproducing or transmitting the material or portions thereof in any form or by any electronicor mechanical means including any information storage or retrieval system, you must obtain priorwritten permission from Houghton Mifflin Company, unless such use is expressly permitted by federalcopyright law. If you wish to reproduce material acknowledging a rights holder other than HoughtonMifflin Company, you must obtain permission from the rights holder. Address inquiries to CollegePermissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 222 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA 02116-3764.Printed in the U.S.A.ISBN: 0-618-52830-X

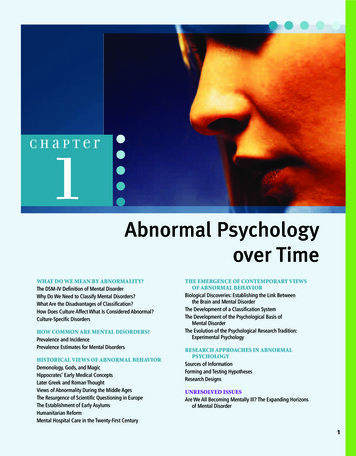

ContentsPREFACE. VTHE CASE OF STEVEN V. . VIIICHAPTER 1 - ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR . 1CHAPTER 2 - MODELS OF ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR . 17CHAPTER 3 - ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR . 35CHAPTER 4 - THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD IN ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY . 52CHAPTER 5 - ANXIETY DISORDERS. 70CHAPTER 6 - DISSOCIATIVE DISORDERS AND SOMATOFORM DISORDERS . 87CHAPTER 7 - PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS AFFECTING MEDICAL CONDITIONS. 102CHAPTER 8 - PERSONALITY DISORDERS AND IMPULSE CONTROL DISORDERS. 119CHAPTER 9 - SUBSTANCE-RELATED DISORDERS . 134CHAPTER 10 - SEXUAL AND GENDER IDENTITY DISORDERS . 152CHAPTER 11 - MOOD DISORDERS . 170CHAPTER 12 - SUICIDE. 190CHAPTER 13 - SCHIZOPHRENIA: DIAGNOSIS AND ETIOLOGY . 207CHAPTER 14 - COGNITIVE DISORDERS . 237CHAPTER 15 - DISORDERS OF CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE . 258CHAPTER 16 - EATING DISORDERS AND SLEEP DISORDERS. 270CHAPTER 17 - THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS . 280CHAPTER 18 - LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES IN ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY . 297Copyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

PrefaceThis Instructor’s Manual is designed for instructors to use in conjunction with the Eighth Edition ofUnderstanding Abnormal Behavior by Sue/Sue/Sue. It is meant to be both a guide to using the text anda handy reference, filled with numerous teaching aids and ideas for enlivening classroom presentations.Whether novice or expert, each instructor should be able to select material from these resources to suithis or her needs.ORGANIZATION OF THIS MANUALThe Chapters. This manual contains eighteen chapters that correspond to the textbook chapters. Eachchapter in the manual is filled with teaching suggestions and resources designed to enhance teachingand learning.CHAPTER-BY-CHAPTER ORGANIZATIONChapter Outlines Chapter outlines are one of the most important features in any Instructor’s Manual.The outlines in this manual are very detailed and highlight critical information for student mastery.Instructors can follow the outlines and be assured that they will cover all the key material in eachchapter, or instructors can edit the outlines to accommodate their own teaching objectives.Learning Objectives Learning objectives, intended to aid students’ mastery of essential facts andconcepts, appear in both the Instructor’s Resource Manual and the student Study Guide; text pagescorresponding to the objectives are also identified. In addition, multiple-choice questions in the TestBank are keyed to the learning objectives. This interactive approach to learning is unique and designedto maximize students’ understanding of text material.Classroom Topics for Lecture and Discussion At least three topics for classroom lectures anddiscussions are given in each chapter. We have chosen topics that are current, complex, and interestingto students—ones we hope will encourage them to connect abstract principles and theories to their dailylives. Also, throughout the chapters we have added topics that allow students to think clinically andmake differential diagnoses. Internet annotations are included to support key topics in this section.These Internet annotations will allow you to have the most current information on a specific topic, thusenhancing your lectures.Classroom Demonstrations Every chapter contains at least three classroom demonstrations, selectedfor their ability to draw students into many of the issues and challenges confronting abnormalpsychology. Many of the demonstrations come with handouts that can easily be removed from theperforated manual and copied for classroom use. Internet annotations for the classroom demonstrationsare also included in this section. These Internet annotations will allow you to have the most currentinformation on the specific demonstration, thus enhancing your effectiveness.Selected Readings A list of selected readings is supplied in each chapter to support text material andclassroom discussions. The lists comprise many articles and books dealing with important issues inabnormal psychology.Copyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

viPrefaceVideo Resources An annotated list of films and tapes, dealing with high-interest topics in abnormalpsychology, completes each chapter of the Instructor’s Manual. Instructors can use these resources tosupport classroom presentations or as discussion starters.On the Internet Information is provided about web addresses for Internet sites related to abnormalpsychology. Internet addresses are listed, with annotations about sites to visit for general topicspresented in the chapter.ADDITIONAL ANCILLARIES AVAILABLESupplements for InstructorsNew! Abnormal Psych in Film DVD/VHS is a hybrid product that contains clips from popularfilms such as The Deer Hunter, and Apollo Thirteen that illustrate key concepts in abnormalpsychology, as well as thought-provoking footage from documentaries and client interviews. Each clipis accompanied by overviews and discussion questions to help bring the study of abnormal psychologyalive for students. This DVD works in tandem with the Abnormal Psychology, Eighth Edition StudentCD-ROM as a unique learning system. On the Student CD-ROM are select, corresponding video clipswith overviews, multiple-choice and essay questions, designed to stimulate critical thinking about thediagnosis and treatment of various disorders. Punctuate your lecture with engaging videos from theDVD; then have your students use the Student CD-ROM to further study the concepts presented inthose videos.HM ClassPrep CD-ROM with HM TestingThis CD-ROM provides one convenient location fortesting and presentation materials. It contains PowerPoint slides, the Instructor’s Resource Manual, andthe Computerized Test Bank. Our HMTesting program offers delivery of test questions in an easy-touse interface, compatible with both Mac and Windows platforms.Test BankThe Test Bank features 100 multiple-choice and three essay questions (with sampleanswers) per chapter. Each question is labeled with the corresponding text page reference as well as thetype of question being asked for easier test creation. The Test Bank is available on our HM ClassPrepCD-ROM with HM Testing.PowerPoint Slides A completely revamped set of PowerPoint slides is available with the EighthEdition. Each chapter’s show contains dozens of slides that include tables and illustrations that helphighlight the major topics in abnormal psychology. The PowerPoint slides are available on theinstructor web site and the HM ClassPrep CD-ROM with HM Testing.Instructor Website For maximum flexibility, much of the material from the HM ClassPrep CD-ROMis also available on our website, which may be accessed athttp://psychology.college.hmco.com/instructors. Easy to navigate, this site offers a range ofinstructional strategies and tools.Course Cartridges for WebCT and Blackboard Course cartridges for WebCT and Blackboard areavailable for the Eighth Edition, allowing instructors to use text-specific material to create an onlinecourse on their own campus course management system.Supplements for StudentsStudy Guide The Study Guide provides a complete review of the chapter with chapter outlines,learning objectives, fill-in-the-blank review of key terms, and multiple-choice questions. Answers totest questions include an explanation for both the correct answer and incorrect answers.Student CD-ROM The CD that accompanies every copy of the student is designed to reinforceconcepts presented in the textbook as well as provide engaging, interactive activities that sharpenCopyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Prefaceviicritical thinking skills. The CD includes select video clips, accompanied by overviews, multiple-choiceand essay questions, Flashcards, Focus Question Activities, Myth Vs. Reality Exercises, and CaseStudy Exercises, all of which provide extra review of concepts and terms studied in the abnormalpsychology course.Student Website The student web site contains additional study aids, including Ace self-tests,interactive Critical Thinking exercises and multimedia tutorials—all designed to help students improvetheir grades while learning more about abnormal psychology. All web resources may be accessed bylogging onto our website at http://psychology.college.hmco.com/students.Case Studies in Abnormal Psychology Case Studies in Abnormal Psychology, by Clark Clipson,California School of Professional Psychology, and Jocelyn Steer, San Diego Family Institute, contains16 studies and can be shrink-wrapped with the text at a discounted package price. Each case representsa major psychological disorder. After a detailed history of each case, critical-thinking questions promptstudents to formulate hypotheses and interpretations based on the client’s symptoms, family andmedical background, and relevant information. The case proceeds with sections on assessment, caseconceptualization, diagnosis, and treatment outlook, and is concluded by a final set of discussionquestions.Abnormal Psychology in Context: Voices and Perspectives This supplementary text, written byDavid Sattler, College of Charleston, Virginia Shabatay, Palomar College, and Geoffrey Kramer, GrandValley State University, features 40 cases and can be shrink-wrapped with the text at a discountedpackage price. This unique collection contains first-person accounts and narratives written byindividuals who live with a psychological disorder and by therapists, relatives, and others who havedirect experience with someone suffering from a disorder. These vivid and engaging narratives areaccompanied by critical-thinking questions and a psychological concept guide that indicates which keyterms and concepts are covered in each reading.Fred W. WhitfordMontana State Universitywhitford@montana.eduCopyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

The Case of Steven V.A NOTE ABOUT STEVEN V.Readers familiar with previous editions of Understanding Abnormal Behavior will notice that theextended case of Steven V. now appears only in Chapter 2. Recognizing that instructors may want touse all of the Steven V. material, the full text of the case from the Fifth Edition has been included here,as well as this guide to using the case in chapters throughout the current edition of the text.GUIDE TO USING THE CASE OF STEVEN V.Chapter 2 (Models of Abnormal Behavior): This condensed chapter describing six approaches toabnormal behavior is an excellent place to use the Steven V. case. Students can be assigned to use oneor more of the approaches to explain Steven’s behavior, thoughts, and feelings. Written assignments,panel discussions, and debates are activities that can engage students in the important process ofanalyzing this single case from different angles.Chapter 3 (Assessment and Classification of Abnormal Behavior): Because this chapter surveys themany forms that assessment can take, it suggests that Steven V.’s strengths and weaknesses might havebeen assessed in many different ways. Each theoretical orientation emphasizes certain forms of data andusing particular methods to collect them. Again, an assignment requiring students to describe, compare,and contrast assessment approaches taken by clinicians of different theoretical stripes reinforces theimportance of flexible thinking. An integrative approach to assessment, using neurological,psychological, and observational techniques, could be emphasized here since most clinicians areeclectic rather than purist.Chapter 10 (Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders): Some of Steven V.’s symptoms entail violentsexual fantasies. Sexual performance concerns and embarrassment with his genitalia are both relevantto the material in this chapter. His use of sexually violent videos in adolescence illustrates some of thepoints made in the text about a behavioral explanation for sexual disorders. His Oedipal relationshipwith his mother relates to the psychoanalytic explanation.Chapter 11 (Mood Disorders): Bipolar disorder is one of the diagnoses Steven V. received. Here youcan compare the diagnostic criteria for bipolar and major depressive disorder with the symptoms thatSteven displays. Ask students which signs are missing, which are present, and which ones we mustspeculate about.Chapter 12 (Suicide): Steven V. seems like a young man with a high potential for violent behaviordirected either at himself or at others. Have students do a lethality assessment of Steven based on whatthey are told. Give them a reasonable amount of discretion in speculating on the circumstances in whichhe would become more and more suicidal. What kinds of suicide prevention efforts might have beenput in place on his university campus? How might his parents have responded if they knew he wassuicidal?Chapter 15 (Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence): Steven V. is a late adolescent when he arrives atthe university counseling service. Students are likely to see him as having adult disorders. But whatdisorders would have been diagnosed when he was eight or twelve or fifteen? Students can review theinformation on childhood depression, separation anxiety disorder, and conduct disorder to see if theCopyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

The Case of Steven V.ixsymptoms and events in Steven V.’s traumatic childhood match. Ask students what interventions withhis parents might have changed the trajectory of his personality development.Chapter 17 (Therapeutic Interventions): Here, as in Chapters 2 and 3, students have an opportunity todescribe, differentiate, and critique the use of different theoretical approaches with one case. Writtenassignments, panel discussions, debates, or role-played “therapy sessions” can impress upon studentshow different therapies would highlight different aspects of Steven’s behavior, thoughts, and feelings.Once again, you could ask students to design an integrative approach that would take the best of themany approaches described to effectively treat him and, perhaps, his family. Family therapy is aparticularly intriguing option for Steven. The conflict between and among him, his father, and hismother may trigger some strong reactions from students who often face similar, if less intense,circumstances. An entertaining and thought-provoking activity is to have students role-play a familytherapy session with the V. family.Chapter 18 (Legal and Ethical Issues in Abnormal Psychology): Clearly, a key issue in the case ofSteven V. is the dilemma faced by his therapist. Should the therapist take seriously Steven’s threats andbreak confidentiality or keep these secrets? Students should see the links between the Tarasoff rulingand the case of Steven V. They can also think about the means by which a therapist attempts to predictdangerousness. Ask students what evidence from the past would indicate that Steven was prepared toharm his former girlfriend; have them assess the risks of overpredicting dangerousness versus the risksof underpredicting it. Finally, compare the list of exemptions from privileged communications given inthe text and the situation the counseling center therapist found himself in when Steven discussed hisplans to harm his girlfriend.Copyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

xThe Case of Steven V.THE CASE OF STEVEN V.Steven V. had been suffering from a severe bout of depression. Eighteen months earlier, Steve’s womanfriend, Linda, had broken off her relationship with Steve. Steve had fallen into a crippling depression.During the past few weeks, however, with the encouragement of his therapist, Steve had begun to openup and express his innermost feelings. His depression had lifted, but it was replaced by a deep angerand hostility toward Linda. In today’s session, Steve had become increasingly loud and agitated as herecounted his complaints against Linda. Minutes ago, with his hands clenched into fists, his knuckleswhite, he had abruptly lowered his voice and looked his therapist in the eye. “She doesn’t deserve tolive,” Steve had said. “I swear, I’m going to kill her.”The therapist could feel himself becoming tense, apprehensive, and uncertain: How should he interpretthe threat? How should he act on it? One wheel of his swivel chair squealed sharply, breaking thesilence, as he backed away from his client.Until this session, the therapist had not believed Steve was dangerous. Now he wondered whether Stevecould be the one client in ten thousand to act out such a threat. Should Linda or the police be told ofwhat Steve had said?Steve V. had a long psychiatric history, beginning well before he first sought help from the therapist atthe university’s psychological services center. (In fact, his parents wanted their son to continue seeing aprivate therapist, but Steven stopped therapy during his junior year at the university.) Steve had actuallybeen in and out of psychotherapy since kindergarten; while in high school, he was hospitalized twicefor depression.His case records, nearly two inches thick, contained a number of diagnoses, including labels such asschizoid personality, paranoid schizophrenia, and manic-depressive psychosis (now referred to asbipolar mood disorder). Although his present therapist did not find these labels particularly helpful,Steve’s clinical history did provide some clues to the causes of his problems.Steven V. was born in a suburb of San Francisco, California, the only child of an extremely wealthycouple. His father was a prominent businessman who worked long hours and traveled frequently. Onthose rare occasions when he was at home, Mr. V. was often preoccupied with business matters andheld himself quite aloof from his son. The few interactions they had were characterized by his constantridicule and criticism of Steve. Mr. V. was greatly disappointed that his son seemed so timid, weak, andwithdrawn. Steven was extremely bright and did well in school, but Mr. V. felt that he lacked the“toughness” needed to survive and prosper in today’s world. Once, when Steve was about ten years old,he came home from school with a bloody nose and bruised face, crying and complaining of beingpicked on by his schoolmates. His father showed no sympathy but instead berated Steve for losing thefight. In his father’s presence, Steve usually felt worthless, humiliated, and fearful of doing or sayingthe wrong thing.Mrs. V. was very active in civic and social affairs, and she too spent relatively little time with her son.Although she treated Steve more warmly and lovingly than his father did, she seldom came to Steve’sdefense when Mr. V. bullied him. She generally allowed her husband to make family decisions.When Steve was a child, his mother at times had been quite affectionate. She had often allowed Steveto sleep with her in her bed when her husband was away on business trips. She usually dressedminimally on these occasions and was very demonstrative—holding, stroking, and kissing Steve. Thisbehavior had continued until Steve was twelve, when his mother abruptly refused to let Steve into herbed. The sudden withdrawal of this privilege had confused and angered Steve, who was not certainwhat he had done wrong. He knew, though, that his mother had been quite upset when she awoke onenight to find him masturbating next to her.Copyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

The Case of Steven V.xiMost of the time, however, Steve’s parents seemed to live separately from one another and from theirson. Steve was raised, in effect, by a full-time maid. He rarely had playmates of his own age. Hisbirthdays were celebrated with a cake and candles, but the only celebrants were Steve and his mother.By age ten, Steven had learned to keep himself occupied by playing “mind games,” letting hisimagination carry him off on flights of fantasy. He frequently imagined himself as a powerful figure—Superman or Batman. His fantasies were often extremely violent, and his foes were vanquished onlyafter much blood had been spilled.As Steve grew older, his fantasies and heroes became increasingly menacing and evil. When he wasfifteen, he obtained a pornographic videotape that he viewed repeatedly on a video player in his room.Often, Steve would masturbate as he watched scenes of women being sexually violated. The moreviolent the acts against women, the more aroused he became. He was addicted to the Nightmare on ElmStreet films, in which the villain, Freddie Kruger, disemboweled or slashed his victims to death with hisrazor-sharp glove. Steve now recalls that he spent much of his spare time between the ages of fifteenand seventeen watching X-rated videotapes or violent movies, his favorite being The Texas ChainsawMassacre, in which a madman saws and hacks women to pieces. Steve always identified with thecharacter perpetrating the outrage; at times, he imagined his parents as the victims.At about age sixteen, Steven became convinced that external forces were controlling his mind andbehavior and were drawing him into his fantasies. He was often filled with guilt and anxiety after one ofhis mind games. Although he was strongly attracted to his fantasy world, he also felt that somethingwas wrong with it and with him. After seeing the movie The Exorcist, he became convinced that he waspossessed by the devil.Until this time, Steve had been quiet and withdrawn. In kindergarten the school psychologist haddescribed his condition as autisticlike because Steve seldom spoke, seemed unresponsive to theenvironment, and was socially isolated. His parents had immediately hired a prominent childpsychiatrist to work with Steve. The psychiatrist had assured them that Steve was not autistic but wouldneed intensive treatment for several years. And throughout these years of treatment, Steve never actedout any of his fantasies. With the development of his interest in the occult and in demonic possession,however, he became outgoing, flamboyant, and even exhibitionistic. He read extensively aboutSatanism, joined a “Church of Satan” in San Francisco, and took to wearing a black cape on weekendjourneys into that city. Against his will, he was hospitalized twice by his parents with diagnoses of,respectively, bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia in remission.Steve was twenty-one years old when he met Linda at an orientation session for first-year universitystudents. Linda struck him as different from other women students: unpretentious, open, and friendly.He quickly became obsessed with their relationship. But although Linda dated Steve frequently over thenext few months, she did not seem to reciprocate his intense feelings. She took part in severalextracurricular activities, including the student newspaper and student government, and her willingnessto be apart from him confused and frustrated Steve. When her friends were around, Linda seemedalmost oblivious to Steve’s existence. In private, however, she was warm, affectionate, and intimate.She would not allow sexual intercourse, but she and Steve did engage in heavy petting.Even while he and Linda were dating, Steve grew increasingly insecure about their relationship. He feltslighted by Linda’s friends and began to believe that she disliked him. Several times he accused her ofplotting against him and deliberately making him feel inadequate. Linda continually denied theseallegations. Finally (on one occasion), feeling frightened and intimidated by Steve, she acquiesced tohaving sex with him. Unfortunately, Steve could not maintain an erection. When he blamed her for this“failure” and became verbally and physically abusive, Linda put an end to their relationship and refusedto see him again.Copyright Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

xiiThe Case of Steven V.During the next year and a half, Steve suffered from severe bouts of depression and twice attemptedsuicide by drug overdose. For the past six months, up to the time of his threat, he had been seeing atherapist regularly at the university’s psychological services center.A Biological View of Steven V.How would a psychologist oriented toward biogenic explanations view the case of Steven V.? If Steve’stherapist were so oriented, we believe that he or she would discuss Steve’s behavior in the followingterms.Before I interpret the symptoms displayed by Steven V. and speculate on what they mean, I must stressmy belief that many “mental disorders” have a strong biological basis. I do accept the importance ofenvironmental influences, but in my view, the biological bases of abnormality are too often overlookedby psychologists. This seems clearly to be the case with Steven V.Much of Steve’s medical history is missing from his case records, along with important informationabout his biological and developmental milestones. We do not have the data necessary to chart a familytree, which would show whether other members of his family have suffered from a similar disorder.This lack of information about possible inherited tendencies in Steve’s current behavior pattern is aserious shortcoming.At age fifteen, Steve was given a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder (formerly called manicdepressive psychosis). Pharmacological treatment was moderately effective in controlling hissymptoms. After Steve’s condition became stabilized, lithium carbonate treatment was instituted for aperiod of time, and Steve was free of symptoms during that period. Unfortunately, Steve apparentlydisliked taking medication and did so only sporadically.In any case, evidence documents and supports a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder. Steve displaysthe behaviors associated with this disorder, ranging from manic episodes (elevated mood characterizedby expansiveness, hyperactivity, flight of ideas, and inflated self-esteem) to depressive episodes(depressed mood characterized by loss of interest, feelings of worthlessness, and thoughts of death orsuicide). These symptoms are not of recent origin but probably were evident very early in his life.Steve’s first contact with a mental health professional was with the school psychologist in kindergarten,who described him as “autisticlike.” I believe the child psychiatrist whom Steve subsequently visitedwas correct in saying that Steve was not autistic. The chief symptoms described in his early years,which appeared to indicate autism (social isolation and unresponsiveness), are similar to those ofdepression. I suspect Steve was experiencing a major depressive episode as early as kindergarten, and itmay not have been his first. Unfortunately, we do not have access to Steve’s pediatrician, who mayhave observed even earlier signs of bipolar disorder. What we do have, however, are several statementsfrom his parents indicating that “even at birth, Steve did not respond in the normal way.”Thus the following conclusions can be drawn: Steve’s disorder was evident early in his life, and hesuffered from a chemical imbalance. In spite of a shortage of information, there is some i

Case Studies in Abnormal Psychology Case Studies in Abnormal Psychology, by Clark Clipson, California School of Professional Psychology, and Jocelyn Steer, San Diego Family Institute, contains